The historic but often decrepit buildings of Havana and other colonial Cuban cities couldn't stand up to Hurricane Irma's winds and rainfall, collapsing and killing seven people in one of the highest death tolls from the storm's passage through the Caribbean.

A resident steps on rubble at his collapsed apartment building where two people died during the passing of Hurricane Irma in Havana, Cuba, Monday, Sept. 11, 2017. Cuban state media reported 10 deaths despite the country's usually rigorous disaster preparations. More than 1 million were evacuated from flood-prone areas. (AP Photo/Desmond Boylan)

Authorities said Monday that three more people were killed by falling objects or drowning, pushing the death toll to 10 in Cuba and at least 24 others in the Caribbean. It was Cuba's worst hurricane death toll since 16 died in Hurricane Dennis in 2005.

Most of Cuba's grand old buildings were confiscated from the wealthy and distributed to the poor and middle classes after a 1959 revolution that promised housing, health care and education as universal rights. But with state salaries of about $25 a month and government agencies strapped for cash, most buildings have seen little maintenance in decades.

A speed limit sign stands tilted and a power line that snapped it half lays on a building, after the passage of Hurricane Irma in Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, Sunday, Sept. 10, 2017. The storm ravaged such lush resort islands as St. Martin, St. Barts, St. Thomas, Barbuda and Anguilla. (AP Photo/Ricardo Arduengo)

Tropical rain and sea spray have chewed into unpainted facades and seeped through unpatched roofs. Trees have sprouted from balconies. Iron rebar has rusted, sloughing off chunks of powdery concrete.

Damage wasn't limited to Havana. More than 100 houses in a small town on Cuba's coastline were destroyed in Matanzas Province when Irma swept through the area, leaving hundreds of people homeless.

In every neighborhood, residents talk warily about the buildings that are one hurricane away from total collapse.

People clear debris outside their homes after the passing of Hurricane Irma in Havana, Cuba, Monday, Sept. 11, 2017. (AP Photo/Desmond Boylan)

That hurricane came Saturday and Sunday as Irma ground up the northern coast, sending chest-high seawater six blocks into Central Havana and blasting the city with 60 mph winds.

On Galeano Street in Central Havana, a fourth-floor balcony dropped onto a bus carrying Maria del Carmen Arregoitia Cardona and Yolendis Castillo Martínez, both 27. In the cities of Matanzas, Ciego de Avila and Camaguey, three men in their 50s and 60s died in building collapses. The government noted in a sternly worded press release that each "did not observe the behavior recommended by Civil Defense."

A worker jokes around as crews remove fallen trees and debris after the passage of Hurricane Irma in Havana, Cuba, Monday, Sept. 11, 2017. (AP Photo/Desmond Boylan)

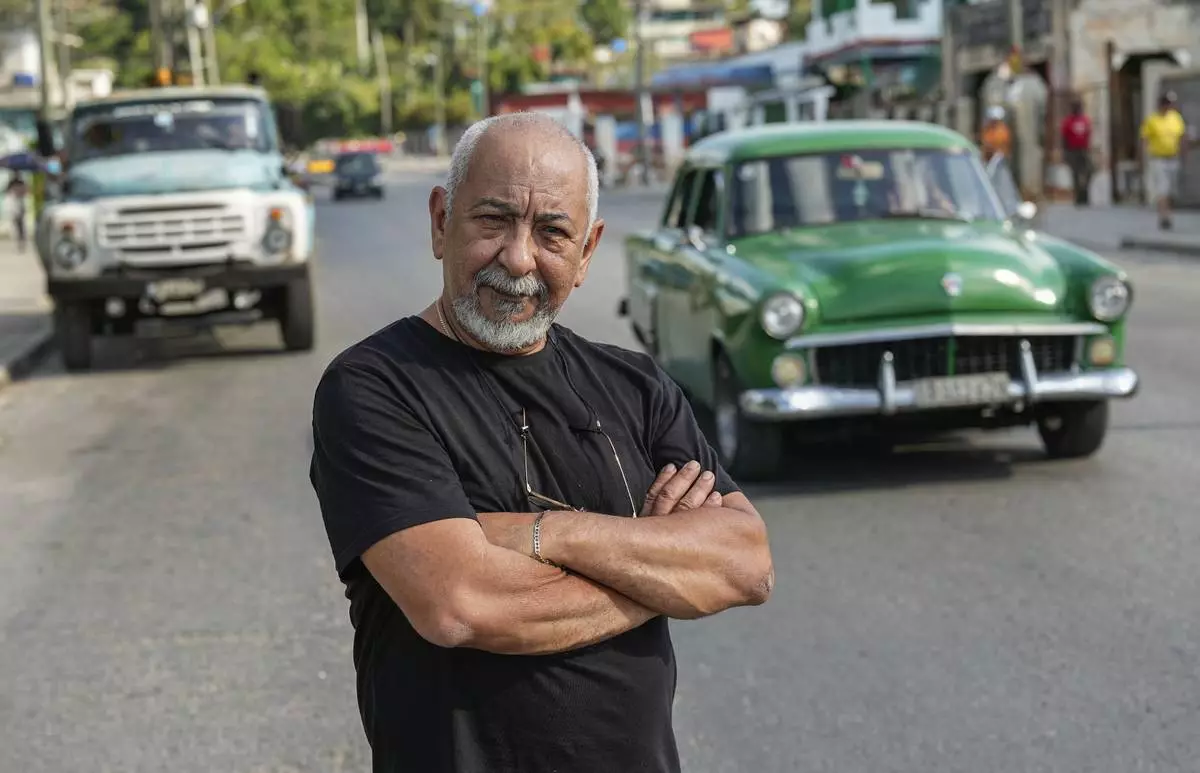

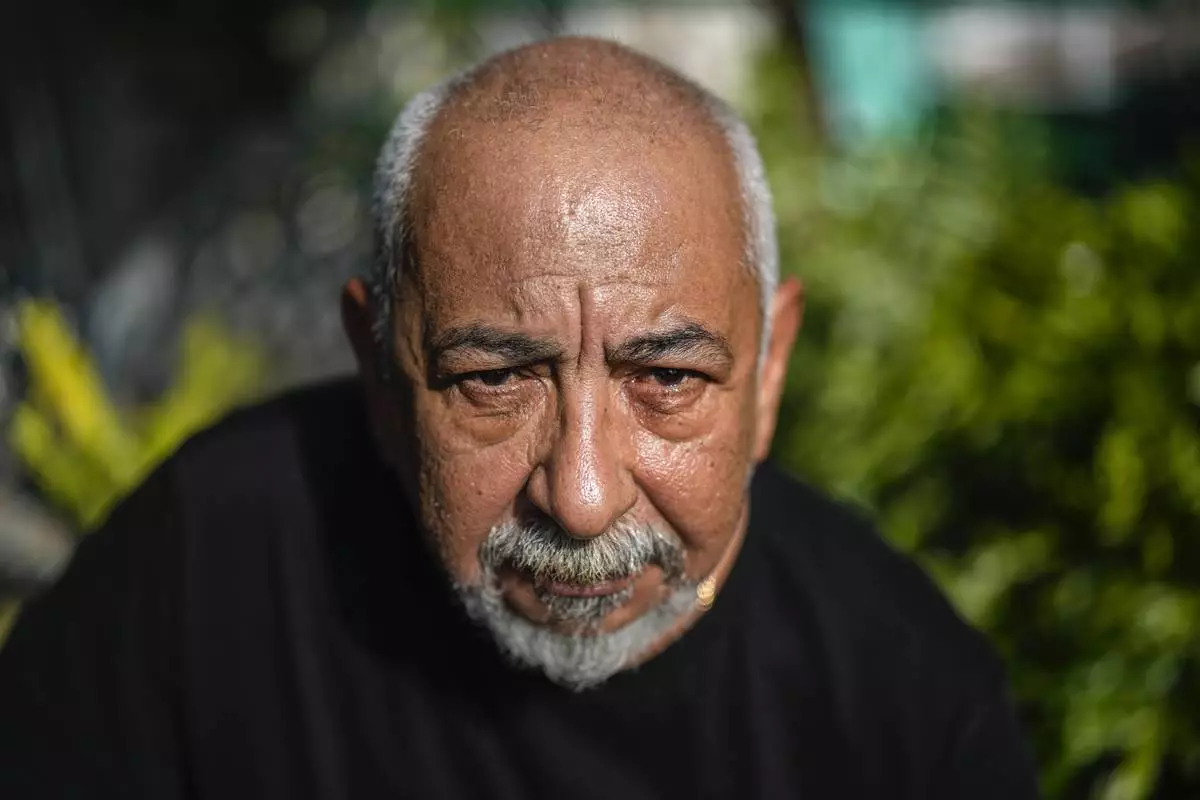

On Animas Street in Central Havana, 51-year-old Walfrido Antonio Valdes Perez was caring for his older brother, Roydis, who worked as a florist until he was diagnosed with HIV. They lived on the second floor of building divided into 11 apartments, many of them divided by crude intermediate floors known as "barbeques."

After midnight, as wind whipped the neighborhood, a wall collapsed onto the roof of their building, crushing the two brothers to death.

No one noticed until the next morning, when neighbors saw a foot sticking out of the rubble.

This photo provided by the Dutch Defense Ministry on Sunday, Sept. 10, 2017, shows people walking toward a cruise ship anchored on St. Maarten, after the passage of Hurricane Irma. Irma cut a path of devastation across the northern Caribbean, including this island that is split between French and Dutch control. (Gerben Van Es/Dutch Defense Ministry via AP)

"We felt something, but no one imagined the roof and barbeque had collapsed," said homemaker Yudisleidis Mederos, 34. "These building are in really bad shape. Their room was the best one."

She and her neighbors remembered Roydis, 54, as a kind and helpful man who had become a virtual family member, helping care for their children, feed them and put them down for naps.

Neighbors said they were ready to evacuate Saturday but emergency officials never asked them to leave.

Boys play on a fallen tree after the passing of Hurricane Irma in Havana, Cuba, Monday, Sept. 11, 2017. (AP Photo/Desmond Boylan)

On Monday, they showed the cracks running through the walls of their building, water leaking through the halls and living spaces, naked metal beams and loose gas pipes and electric cables.

"We've been trying to fix things for years. It's a shame that maybe they'll come now, only after two people have died," said homemaker Laritza Penalver, 49.

Havana was in recovery mode Monday, with crews cleaning away thousands of fallen trees and electric restored to a handful of neighborhoods. Schools were closed until further notice. President Raul Castro issued a message to the nation that didn't mention the deaths, but described damage to "housing, the electrical system and agriculture."

A man walks past debris caused by Hurricane Irma in Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, Sunday, Sept. 10, 2017. The storm ravaged such lush resort islands as St. Martin, St. Barts, St. Thomas, Barbuda and Anguilla. (AP Photo/Ricardo Arduengo)

He also acknowledged destruction in the northern keys where Cuba and foreign hotel management firms have built dozens of all-inclusive beach resorts in recent years. The Jardines del Rey airport serving the northern keys was destroyed, the Communist Party newspaper Granma reported, tweeting photos of a shattered terminal hall littered with debris.

"The storm hit some of our principal tourist destinations but the damage will be repaired before the high season," starting in November, Castro wrote.

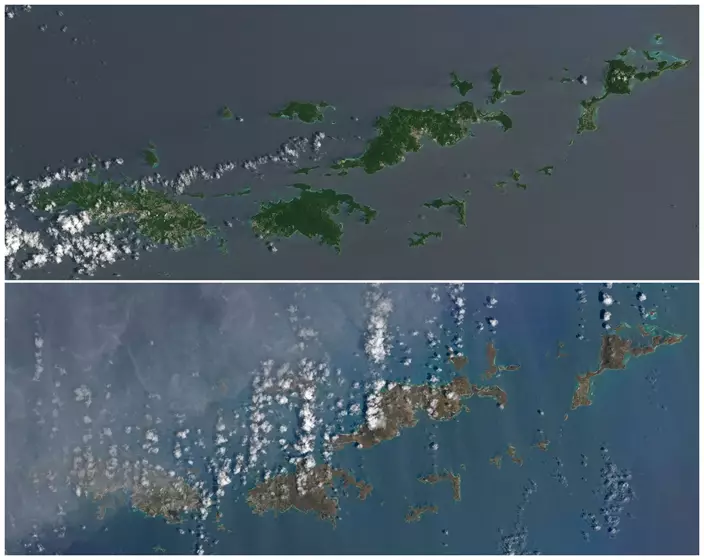

This combo of natural-color images provided by NASA Earth Observatory shows the U.S. and British Virgin Islands islands on Aug. 25, 2017, top, before the the passage of Hurricane Irma, and after the storm passed, on Sept. 10, 2017. The islands, from left, are St. Thomas, St. John, Tortola and Virgin Gorda. Irma passed as a Category 5 storm. (Joshua Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory via AP)

To the east, in the Leeward Islands known as the playground for the rich and famous, governments came under criticism for failing to respond quickly to the hurricane, which flattened many towns and turned lush, green hills to a brown stubble.

Residents have reported food, water and medicine shortages, as well as looting.

British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson defended his government's response to what he called an "unprecedented catastrophe" and promised to increase funding for the relief effort. Britain sent a navy ship and almost 500 troops to the British Virgin Islands, Anguilla and the Turks and Caicos islands.

The U.S. government said it was sending a flight Monday to evacuate its citizens from St. Martin, one of the hardest-hit islands where 10 people were killed. Evacuees were warned to expect long lines and no running water at the airport.

A Royal Caribbean Cruise Line ship was expected to dock near St. Martin to help in the aftermath, and a boat was bringing a 5-ton crane capable of unloading large shipping containers of aid. A French military ship was scheduled to arrive Tuesday with materials for temporary housing.

About 70 percent of the beds at the main hospital in the French portion of St. Martin were severely damaged, and more than 100 people needing urgent medical care were evacuated. Eight of the territory's 11 pharmacies were destroyed, and Guadeloupe was sending medication.

French President Emmanuel Macron was scheduled to arrive in St. Martin on Tuesday to bring aid and fend off criticism that he didn't do enough to respond to the storm.

The "whole government is mobilized" to help, said Interior Minister Gerard Collomb.