After a 20-year voyage, NASA's Cassini spacecraft is poised to dive into Saturn this week to become forever one with the exquisite planet.

There's no turning back: Friday it careens through the atmosphere and burns up like a meteor in the sky over Saturn.

NASA is hoping for scientific dividends up until the end. Every tidbit of data radioed back from Cassini will help astronomers better understand the entire Saturnian system — rings, moons and all.

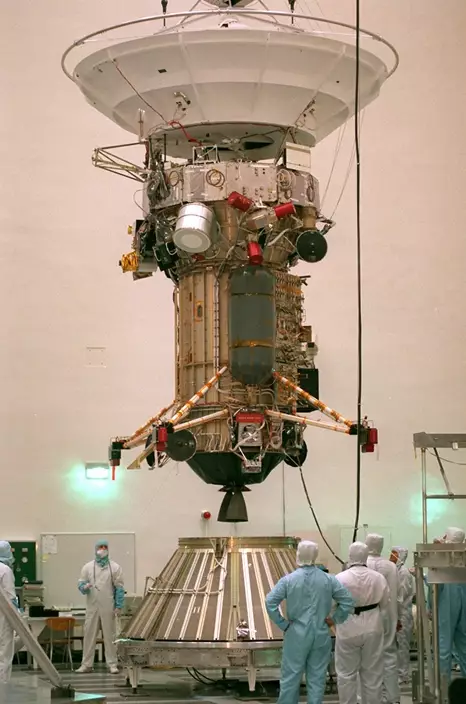

FILE - In this Friday Sept. 20, 1996 file photo, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineers and technicians lower the 3,420-pound Cassini Spacecraft into the Launch-Vehicle-Adapter at JPL in Pasadena, Calif. After a 20-year voyage, the spacecraft is poised to dive into Saturn on Friday, Sept. 15, 2016. (AP Photo/Frank Wiese)

The only spacecraft ever to orbit Saturn, Cassini spent the past five months exploring the uncharted territory between the gaseous planet and its dazzling rings. It's darted 22 times between that gap, sending back ever more wondrous photos.

On Monday, Cassini flew past jumbo moon Titan one last time for a gravity assist— a final kiss goodbye, as NASA calls it, nudging the spacecraft into a deliberate, no-way-out path.

During its final plunge early Friday morning, Cassini will keep sampling Saturn's atmosphere and beaming back data, until the spacecraft loses control and its antenna no longer points toward Earth. Descending at a scorching 76,000 mph (122,000 kph), Cassini will melt and then vaporize. It should be all over in a minute.

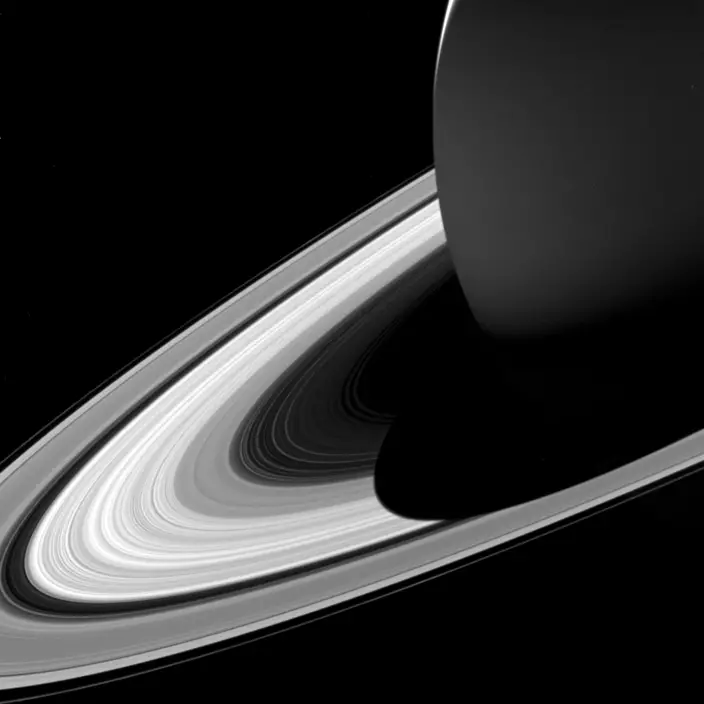

This Feb. 3, 2017 image made available by NASA shows Saturn's shadow on its rings as seen from the Cassini spacecraft. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute via AP)

"The mission has been insanely, wildly, beautifully successful, and it's coming to an end," said NASA program scientist Curt Niebur. "I find great comfort in the fact that Cassini will continue teaching us up to the very last second."

Telescopes on Earth will watch for Cassini's burnout nearly a billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) away. But any flashes will be hard to see given the time — close to high noon at Saturn — and Cassini's minuscule size against the solar system's second largest planet.

The plutonium on board will be the last thing to go. The dangerous substance was encased in super-dense iridium as a safeguard for Cassini's 1997 launch and has been used for electric power to run its instruments. Project officials said once the iridium melts, the plutonium will be dispersed into the atmosphere. Nothing — not even traces of plutonium — should escape Saturn's deep gravity well.

The whole point of this one last exercise — dubbed the Grand Finale — is to prevent the spacecraft from crashing into the moons of Enceladus (ehn-SEHL'-uh-duhs) or Titan. NASA wants future robotic explorers to find pristine worlds where life might possibly exist, free of Earthly contamination.

It's inevitable that the $3.9 billion U.S.-European mission is winding down. Cassini's fuel tank is almost empty, and its objectives have been accomplished many times over since its 2004 arrival at Saturn following a seven-year journey.

The leader of Cassini's imaging team, planetary scientist Carolyn Porco, already feels the loss.

"There's another part of me that's just, 'It's time. We did it.' Cassini was so profoundly, scientifically successful," said Porco, a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. "It's amazing to me even, what we were able to do right up until the end."

Until Cassini, only three spacecraft had ventured into Saturn's neighborhood: NASA's Pioneer 11 in 1979 and Voyager 1 and 2 in the early 1980s. Those were just flybys, though, and offered fleeting glances. And so Cassini and its traveling companion, the Huygens (HOY'-gens) lander, actually provided the first hard look at Saturn, its rings and moons. They are named for 17th-century astronomers, Italian Giovanni Domenico Cassini and Dutch Christiaan Huygens, who spotted Saturn's first moon, Titan. The current count is 62.

Cassini discovered six moons — some barely a mile or two across — as well as swarms of moonlets that are still part of Saturn's rings.

All told, Cassini has traveled 4.9 billion miles (7.9 billion kilometers) since launch, orbited Saturn nearly 300 times and collected more than 453,000 pictures and 635 gigabytes of scientific data.

The European Space Agency's Huygens lander — which hitchhiked all the way to Saturn aboard Cassini — still rests on Titan. It parachuted down in 2005, about six months after Cassini arrived at Saturn, and relayed data for more than an hour from the moon's frigid surface.

Still believed intact, Huygens remains the only spacecraft to actually land in one of our outer planetary systems.

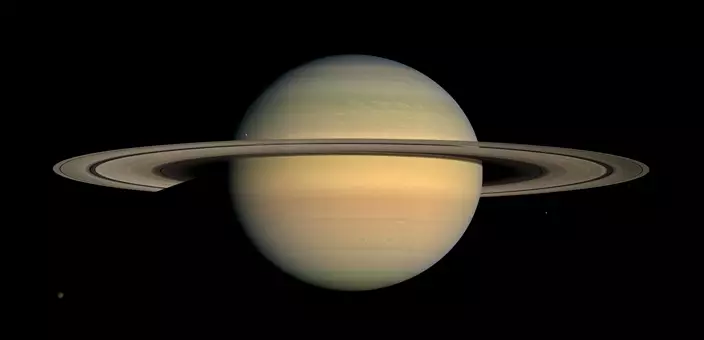

This July 23, 2008 image made available by NASA shows the planet Saturn, as seen from the Cassini spacecraft. After a 20-year voyage, Cassini is poised to dive into Saturn on Friday, Sept. 15, 2016. (NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute via AP)

Other than Titan's size — about as big as Mercury — little was known about Saturn's biggest and haze-covered moon before Cassini and Huygens showed up. They revealed seas and lakes of methane and ethane at Titan — the result of rainfall — and provided evidence of an underground ocean, quite possibly a brew of water and ammonia.

Over at the little moon Enceladus, Cassini unveiled plumes of water vapor spewing from cracks at the south pole. These geysers are so tall and forceful that they actually blast icy particles into one of Saturn's rings. Thanks to Cassini, scientists believe water lies beneath the icy surface of Enceladus, making it a prime spot to look for traces of potential life.

"Enceladus has no business existing and yet there it is, practically screaming at us, 'Look at me. I completely invalidate all of your assumptions about the solar system.'" Niebur said. "It's an amazing destination."

That's precisely why scientists didn't want to risk Cassini crashing into it, said program manager Earl Maize at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

"The book is not complete. There's more to come" from exploring the planets, Maize said. "But this has been a marvelous ride."