Fisherman Jake Bunch leans over the side of the fishing boat "Sadie K," spears his catch, and reels it aboard: an abandoned crab pot, dangling one limp lasagna noodle of kelp and dozens of feet of rope, just the kind of fishing gear that has been snaring an increasing number of whales off U.S. coasts.

In this Monday, Aug. 7, 2017 photo, a buoy marker for an abandoned crab pot floats off Half Moon Bay, Calif. Fisherman like Jake Bunch are using GPS positioning in their cellphones to voluntarily step up recovery of abandoned crab pots before they snare whales. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

Confirmed counts of humpbacks, blue and other endangered or threatened species of whale entangled by the ropes, buoys and anchors of fishing gear hit a record 50 on the East Coast last year, and tied the record on the West Coast at 48, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The accidental entanglements can gouge whales' flesh and mouth, weaken the animals, drown them, or kill them painfully, over months.

Click to Gallery

Fisherman Jake Bunch leans over the side of the fishing boat "Sadie K," spears his catch, and reels it aboard: an abandoned crab pot, dangling one limp lasagna noodle of kelp and dozens of feet of rope, just the kind of fishing gear that has been snaring an increasing number of whales off U.S. coasts.

Confirmed counts of humpbacks, blue and other endangered or threatened species of whale entangled by the ropes, buoys and anchors of fishing gear hit a record 50 on the East Coast last year, and tied the record on the West Coast at 48, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The accidental entanglements can gouge whales' flesh and mouth, weaken the animals, drown them, or kill them painfully, over months.

Especially stormy weather this year has meant more wayward crabbing gear than usual, Bunch said recently on a gray late-summer morning at sea.

The crab gear goes back to Bunch's port, which charges the original owners $100 for returning the lost gear — a bargain, compared to the $250 a new pot costs.

Dungeness bring in tens of millions of dollars in revenue in a good year. But they also are the single-largest identifiable source of fishing gear entangling whales on the West Coast. Crab pots and the lines can get carried away by waves or by vessels that accidentally snag them. Sometimes fishermen abandon their pots or lose them.

Clearly, "taking gear off the whales is not the solution to the problem. At all," said Justin Viezbicke, who tracks West Coast entanglements for NOAA federal fisheries. The answer is "prevent these things from happening in the future."

Some environmental groups say the state should put in place more mandatory protection measures, such as blocking fishermen from especially important waters for whales.

"We've been hearing for years now from both the state of California and fishermen that they care about the problem and want to address it," said Kristen Monsell, a staff attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity.

This year, Bunch is one of small number of commercial fishermen out of Half Moon Bay, south of San Francisco, and five other ports up and down California who headed to sea again after the West Coast's Dungeness crab season ended this summer.

The California fishermen are part of a new effort using their cellphones' GPS and new software pinpointing areas where lost or abandoned crabbing gear has been spotted. They retrieve the gear for a payment — at Half Moon Bay, it's $65 per pot —before the fishing ropes can snag a whale.

In this Monday, Aug. 7, 2017 photo, Jake Bunch scrapes off growth to read the identification tag of an abandoned crab pot off Half Moon Bay, Calif. Fisherman like Bunch are using GPS positioning in their cellphones to voluntarily step up recovery of abandoned crab pots before they snare whales. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

Especially stormy weather this year has meant more wayward crabbing gear than usual, Bunch said recently on a gray late-summer morning at sea.

"Makes it all the more important to pick it up," he says.

Bunch spots the algae-blackened buoy of his first derelict crab pot of the day just after a humpback surfaces near the Sadie K.

Leaning out the window of his boat's cabin, Bunch uses his phone to snap a picture of the spot, capturing its location via the GPS setting. Then he hauls in the crab pot, the size and shape of a giant truck tire, and removes the owner's tag inside that California mandates. He tosses the lone live crab inside the pot back into the water — it's the offseason.

In this Monday, Aug. 7, 2017 photo, Jake Bunch, left, and Tom Dempsey, right, of the Nature Conservancy haul up an abandoned crab pot off Half Moon Bay, Calif. Fisherman like Bunch are using GPS positioning in their cellphones to voluntarily step up recovery of abandoned crab pots before they snare whales. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

The crab gear goes back to Bunch's port, which charges the original owners $100 for returning the lost gear — a bargain, compared to the $250 a new pot costs.

California fishermen and port officials working with the Nature Conservancy environmental group developed the program, designed to be affordable and easy enough for ports to manage on their own.

West Coast fishermen annually lose thousands of pots for Dungeness crabs, which are a staple of Thanksgiving dinners and community crab feeds across California.

In this Monday, Aug. 7, 2017 photo, Jake Bunch uses his phone to mark the position of an abandoned crab pot off Half Moon Bay, Calif. Fisherman like Bunch are using GPS positioning in their cellphones to voluntarily step up recovery of abandoned crab pots before they snare whales. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

Dungeness bring in tens of millions of dollars in revenue in a good year. But they also are the single-largest identifiable source of fishing gear entangling whales on the West Coast. Crab pots and the lines can get carried away by waves or by vessels that accidentally snag them. Sometimes fishermen abandon their pots or lose them.

On the East Coast, meanwhile, lobster traps and gillnets are among the culprits in whale entanglements.

On both coasts, fishermen and others regularly join missions to cut free whales found tangled in gear. Last July, a Canadian fisherman was killed while rescuing an Atlantic right whale snagged by lines.

In this Monday, Aug. 7, 2017 photo, Jake Bunch, left, and Tom Dempsey, right, of the Nature Conservancy gather abandoned crab pots they hauled up off Half Moon Bay, Calif. Fisherman like Bunch are using GPS positioning in their cellphones to voluntarily step up recovery of abandoned crab pots before they snare whales. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

Clearly, "taking gear off the whales is not the solution to the problem. At all," said Justin Viezbicke, who tracks West Coast entanglements for NOAA federal fisheries. The answer is "prevent these things from happening in the future."

Off the West Coast, changes in ocean temperatures in recent years mean fishermen and whales increasingly have found themselves in the same waters.

The surge in whale entanglements has fueled tensions in California between commercial fishing operators eager to show they are trying to tackle the problems and some conservationists.

In this Monday, Aug. 7, 2017 photo, a humpback whale breeches off Half Moon Bay, Calif. California’s Dungeness crab season has ended but the fishermen who go after Dungeness are back at sea.

Commercial fishermen at Half Moon Bay and five other California ports this year are using cellphone GPS to help recover abandoned crabbing gear that can snare and kill whales. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

Some environmental groups say the state should put in place more mandatory protection measures, such as blocking fishermen from especially important waters for whales.

One group, the Center for Biological Diversity, filed notice this summer that it plans to sue California for allegedly not doing enough to keep the Dungeness crab fishery from killing protected whale species.

In this Monday, Aug. 7, 2017 photo, a crab sits in an abandoned crab pot off Half Moon Bay, Calif. Fisherman are using GPS positioning in their cellphones to voluntarily step up recovery of abandoned crab pots before they snare whales. Some environmental groups say the state should put in place more mandatory protection measures, such as blocking fishermen from especially important waters for whales. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

"We've been hearing for years now from both the state of California and fishermen that they care about the problem and want to address it," said Kristen Monsell, a staff attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity.

"But nothing has changed other than more whales are getting tangled off our coast and dying painful, tragic deaths," Monsell said.

On this morning, Bunch quickly reels in nine derelict crab pots in fewer than two hours.

In this photo taken Monday, Aug. 7, 2017, Tom Dempsey of the Nature Conservancy shows off the locations of abandoned crab pots that have been recovered off Half Moon Bay, Calif. Fisherman are using GPS positioning in their cellphones to voluntarily step up recovery of abandoned crab pots before they snare whales. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

Back at Half Moon Bay port, Lisa Damrosch, executive director of the local seafood marketing association, has taken in about 450 recovered crab pots so far this year, stacking them behind a fence to return them to their owners before the crucial holiday season for Dungeness crab.

"No one wants to entangle a single whale," Damrosch said. But "the best fishermen in the world are going to lose a pot."

WASHINGTON (AP) — For Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell and House Speaker Mike Johnson, the necessity of providing Ukraine with weapons and other aid as it fends off Russia's invasion is rooted in their earliest and most formative political memories.

McConnell, 82, tells the story of his father’s letters from Eastern Europe in 1945, at the end of World War II, when the foot soldier observed that the Russians were “going to be a big problem” before the communist takeover to come. Johnson, 30 years younger, came of age as the Cold War was ending.

As both men pushed their party this week to support a $95 billion aid package that sends support to Ukraine, as well as Israel, Taiwan and humanitarian missions, they labeled themselves “Reagan Republicans” an described the fight against Russian President Vladimir Putin in terms of U.S. strength and leadership. But the all-out effort to get the legislation through Congress left both of them grappling with an entirely new Republican Party shaped by former President Donald Trump.

While McConnell, R-Ky., and Johnson, R-La., took different approaches to handling Trump, the presumptive White House nominee in 2024, the struggle highlighted the fundamental battle within the GOP: Will conservatives continue their march toward Trump’s “America First” doctrine on foreign affairs or will they find the value in standing with America's allies? And is the GOP still the party of Ronald Reagan?

“I think we’re having an internal debate about that,” McConnell said in an interview with The Associated Press. “I’m a Reagan guy and I think today — at least on this episode — we turned the tables on the isolationists.”

Still, he acknowledged, “that doesn’t mean they’re going to go away forever.”

McConnell, in the twilight of his 18-year tenure as Republican leader, lauded a momentary victory Tuesday as a healthy showing of 31 Republicans voted for the foreign aid; that was nine more than had supported it in February. He said that was a trend in the right direction.

McConnell, who has been in the Senate since 1985, said passing the legislation was “one of the most important things I’ve ever dealt with where I had an impact."

But it wasn’t without cost.

He said last month he would step away from his job as leader next year after internal clashes over the money for Ukraine and the direction of the party.

For Johnson, just six months into his job as speaker, the political crosscurrents are even more difficult. He is clinging to his leadership post as right-wing Republicans threaten to oust him for putting the aid to Ukraine to a vote. While McConnell has embraced American leadership abroad his entire career, Johnson only recently gave complete support to the package.

Johnson has been careful not to portray passage as a triumph when a majority of his own House Republicans opposed the bill. He skipped a celebratory news conference afterward, describing it as “not a perfect piece of legislation” in brief remarks.

But he also borrowed terms popularized by Reagan, saying aggression from Russia, China and Iran “threatens the free world and it demands American leadership.”

“If we turn our backs right now, the consequences could be devastating,” he said.

Hard-line conservatives, including some who are threatening a snap vote on his leadership, are irate, saying the aid was vastly out of line with what Republican voters want. They condemned both Johnson and McConnell for supporting it.

“House Republican leadership sold out Americans and passed a bill that sends $95 billion to other countries,” said Republican Sen. Tommy Tuberville of Alabama, who opposed the bill. He said the legislation "undermines America's interests abroad and paves our nation's path to bankruptcy.”

Johnson has been lauded by much of Washington for doing what he called “the right thing" at a perilous moment for himself and the world.

“He is fundamentally an honorable person,” said Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., who brokered the negotiations and spent hours on the phone and in meetings with Johnson, McConnell and the White House.

Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, said Johnson and McConnell “both showed great resolve and backbone and true leadership at a time it was desperately needed.”

When McConnell began negotiations over President Joe Biden's initial aid request last year, he quickly set the terms for a deal. He and Schumer agreed to pair any aid for Ukraine with help for Israel, Schumer said, and McConnell demanded policy changes at the U.S. border with Mexico.

On McConnell's mind, he said, was that Trump was “unenthusiastic” about providing more aid to Kyiv. Yet McConnell, whose office displays a portrait of every Republican president since Reagan with the exception of Trump, had a virtually nonexistent relationship with the man he often refers to not by name, but simply as “the former president.”

Still, Trump would prove to hold powerful sway. When a deal on border security neared completion after months of work, Trump eviscerated the proposal as insufficient and a “gift” to Biden's reelection. Conservatives, including Johnson, rejected it out of hand.

With the border deal dead, McConnell pushed ahead with Schumer on the foreign aid, with the border policies stripped out, solidifying their unusual alliance. The Senate leaders met weekly throughout the negotiation.

“We disagreed on a whole lot, but we really stuck together,” Schumer said.

“We just persisted. We could not give up on this."

Meanwhile, a small group of GOP senators began working on an idea they thought could give Johnson some political wiggle room. Sens. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, Kevin Cramer of North Dakota and Markwayne Mullin of Oklahoma took an idea that Trump had raised — structuring the aid to Ukraine as a loan — and tried to make it reality.

Through a series of phone calls with Trump, several House members, as well as the speaker, they worked to structure roughly $9 billion in economic aid for Ukraine as forgivable loans — just as it was in the final package.

“Our approach this time was to make sure that the politics were set, meaning that President Trump is on board,” Mullin said.

The conversations culminated in Johnson making a quick jaunt to Florida, where he stood side by side with Trump at his Florida club just days before moving ahead with the Ukraine legislation in the House.

It was all enough, with Democratic help, to get the bill across the finish line. The legislation, which Biden signed into law on Wednesday, included some revisions from the Senate bill, including the loan structure and a provision to seize frozen Russian central bank assets to rebuild Ukraine. Nine GOP senators who had opposed the first version of the bill swung to “yes” largely because of the changes Johnson had made.

The result was a strong showing for the foreign aid in the Senate, even though the decision could prove costly for Johnson.

What comes next on Ukraine is anyone's guess.

While the $61 billion for Ukraine in the package is expected to help the country withstand Moscow's offensive this year, more assistance will surely be needed. Republicans, exhausted after a grueling fight, largely shrugged off questions about the future.

“This one wasn’t easy,” Mullin said.

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

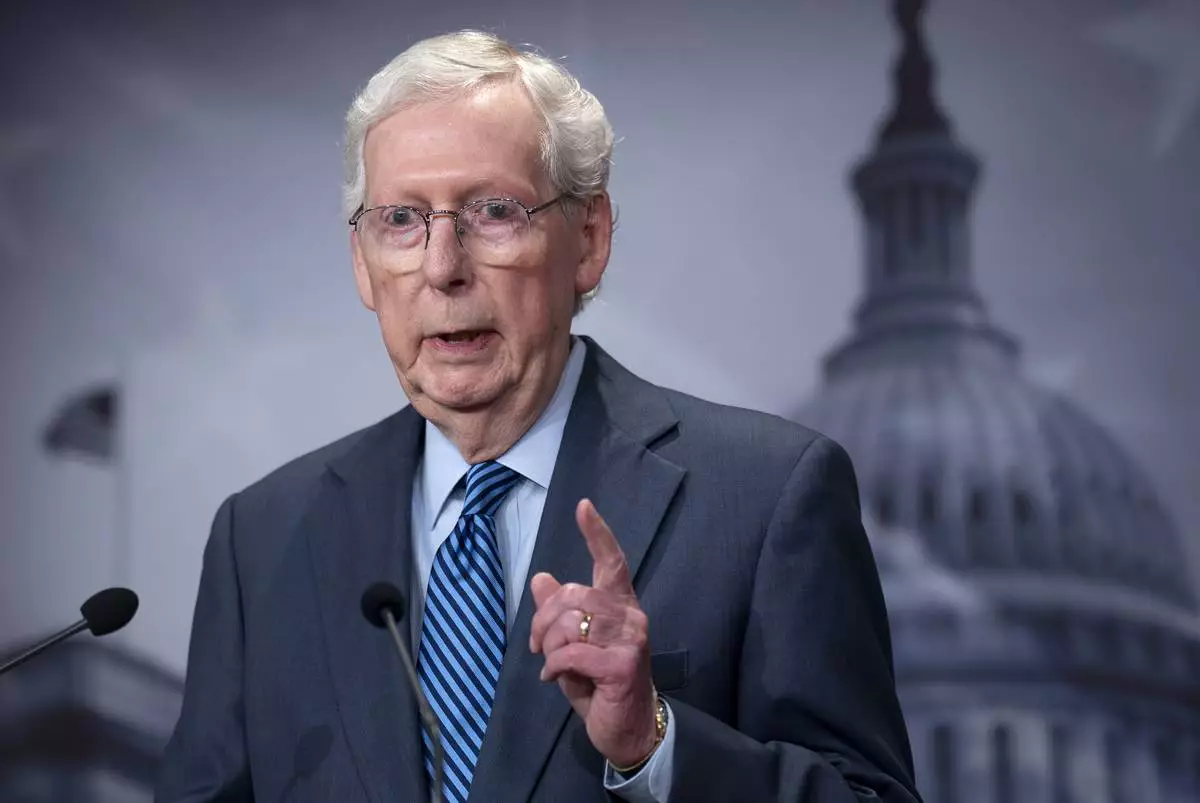

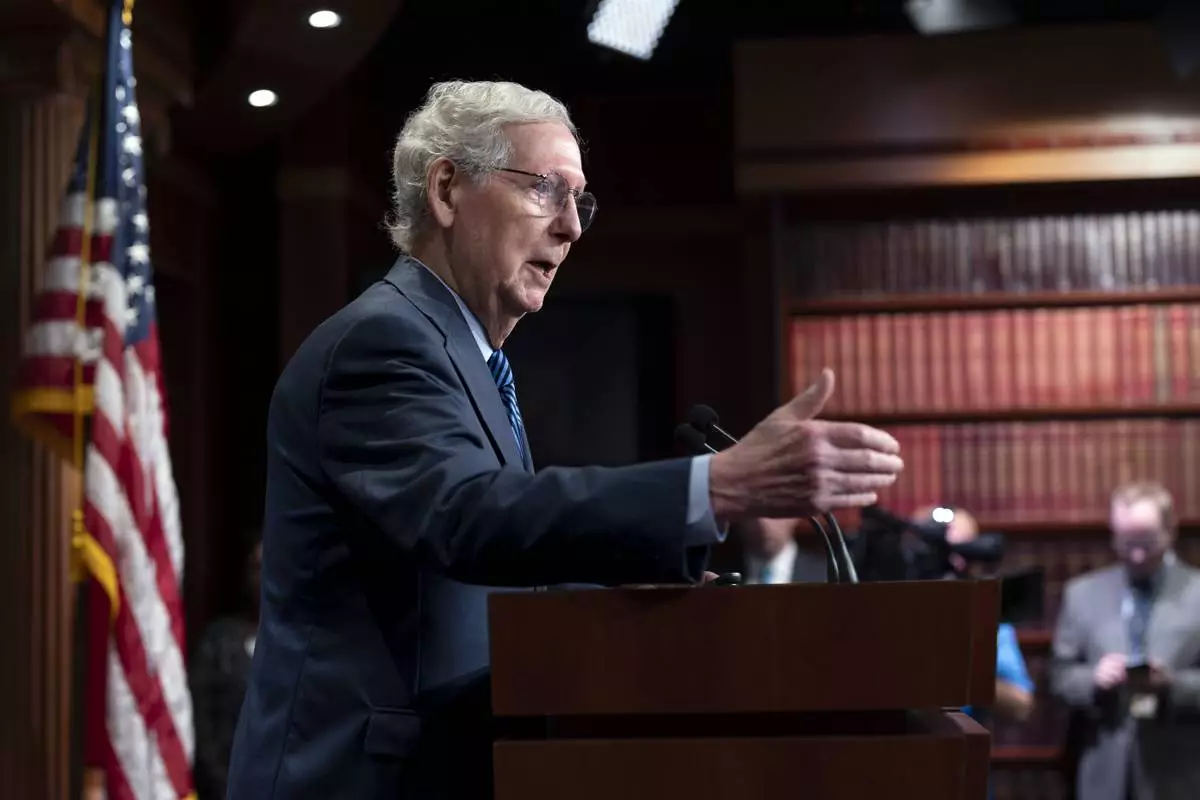

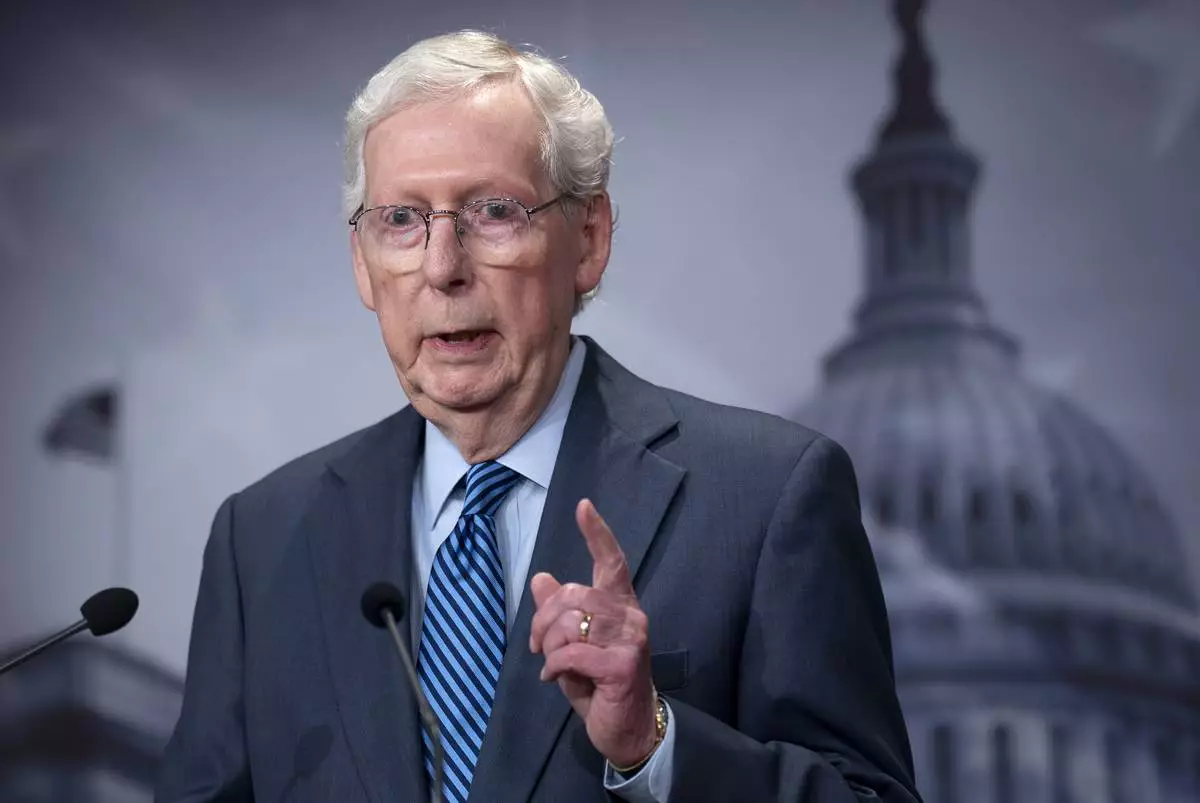

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., praises support for Ukraine as the Senate is on track to pass $95 billion in war aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., praises support for Ukraine as the Senate is on track to pass $95 billion in war aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., walks to the chamber as the Senate prepares to advance the $95 billion aid package for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan passed by the House, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)