Inside the Francisco Kino Elementary School a miniature city has emerged at the site of a shelter for people who lost their homes in last week's deadly earthquake.

On the school's open-air courtyard, doctors test blood pressure and glucose levels at a makeshift triage center set up on a plastic table. Nearby, children get haircuts while stressed-out parents receive massages.

Click to Gallery

Inside the Francisco Kino Elementary School a miniature city has emerged at the site of a shelter for people who lost their homes in last week's deadly earthquake.

But frustration is growing inside the gym, where families camp out on mattresses alongside piles of new, donated belongings. Days without easy access to a shower and the loss of simple liberties like deciding when to turn out a light to go to asleep have become aggravating.

Officials pledged Tuesday to give families chased from their homes a monthly payment of 3,000 pesos — the equivalent of about $170 — to find a new place to live for a total of three months. But an average one-bedroom apartment outside Mexico City's center can easily run twice as much.

"Sorry to interrupt you," one elderly woman sitting on a donated mattress said at a meeting with a visiting representative from Mexico City's Women's Institute. "They tell us if we leave here, we'll lose our shelter. But if we don't go there, we might miss out on government benefits."

In all, some 43 shelters across the capital have tended to 24,000 people since the Sept. 19 quake, though many came just for a plate of food before finding a place to stay with friends or family.

Dr. Misael Dominguez, an attending physician, said doctors have "practically everything we require."

To the left of the entrance are signs offering psychological services. Many of those sheltering at the school have arrived with the quake's trauma still weighing heavily on their minds.

Night can bring the hardest hours. A lucky few have donated mattresses, but most are sleeping on uncomfortable foam mats. They get a few hours of sleep at best. Wary of sharing a collective space, no one feels entitled to tell someone else to be quiet or turn out a light.

Volunteers organize supplies at the Francisco Kino school, which was turned into a temporary shelter for residents evacuated from the large apartment complex in the Tlalpan neighborhood of Mexico City, Monday, Sept. 25, 2017. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

But frustration is growing inside the gym, where families camp out on mattresses alongside piles of new, donated belongings. Days without easy access to a shower and the loss of simple liberties like deciding when to turn out a light to go to asleep have become aggravating.

They want to know: How long will they be stuck here?

"This is like a horror story," said Ana Maria Castaneda, 49, who is living at the shelter with five relatives.

More than 12,000 people whose homes were destroyed or damaged by the magnitude 7.1 quake have spent at least one night in a shelter since the quake, the Mexican government says.

Eduardo Alvarez plays his guitar inside a tent with his pet dogs Lucas and Peluche at the Francisco Kino school, which was turned into a temporary shelter for residents evacuated from the large apartment complex in the Tlalpan neighborhood of Mexico City, Monday, Sept. 25, 2017. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Officials pledged Tuesday to give families chased from their homes a monthly payment of 3,000 pesos — the equivalent of about $170 — to find a new place to live for a total of three months. But an average one-bedroom apartment outside Mexico City's center can easily run twice as much.

"We will directly support families with resources and materials to repair damages or build a new home," President Enrique Pena Nieto said in a televised address Tuesday night.

Government employees fanned out Tuesday urging the 25 families living at the Francisco Kino school to visit a nearby park where officials have set up areas for victims to sign up for benefits, but the suggestion was met with skepticism and resistance. If they went to the plaza, some people worried, they might lose their coveted spots at the shelter. Some 500 families were forced from nearby apartment buildings after one collapsed and the school had space only for two dozen.

A rescue worker walks down a ladder as the search for people continues amid the rubble of a collapsed apartment complex in the southern neighborhood of Tlalpan of Mexico City, Monday Sept. 25, 2017.(AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

"Sorry to interrupt you," one elderly woman sitting on a donated mattress said at a meeting with a visiting representative from Mexico City's Women's Institute. "They tell us if we leave here, we'll lose our shelter. But if we don't go there, we might miss out on government benefits."

"After the fright of the quake, why are they scaring us with these threats?" she asked.

The residents were urged to go one-by-one to sign up for government assistance, leaving family members to watch over their belongings.

According to Mexico City Mayor Miguel Angel Mancera, inspectors have examined damage at 10,903 properties so far and 83 percent of the structures are safe to live in. That means about 1,800 have been marked uninhabitable.

Florencia Cortes, 37, right, sleeps next to her son Jonatan at the Francisco Kino school, which was turned into a temporary shelter for residents evacuated from the large apartment complex in the Tlalpan neighborhood of Mexico City, Monday, Sept. 25, 2017. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

In all, some 43 shelters across the capital have tended to 24,000 people since the Sept. 19 quake, though many came just for a plate of food before finding a place to stay with friends or family.

It's unclear how long the shelters will be operating. Volunteers and government employees stationed at the Francisco Kino school — a shelter run largely by neighborhood residents — said it would stay open for the foreseeable future.

"As long as is necessary," said Elizabeth Garcia, a government worker inspecting the site Tuesday.

The mountain-like piles of donated water bottles and medical supplies along with the growing level of organized services give the impression of a population that is starting to settle in. Rows of toothbrushes and toothpaste rest on sinks outside a children's bathroom. A room that once held school materials has been fashioned into a space for medical donations. A cardboard box holds mounds of antibiotics. On a desk are Styrofoam cups holding injectable medicines like anti-inflammatories that are labeled with a black marker.

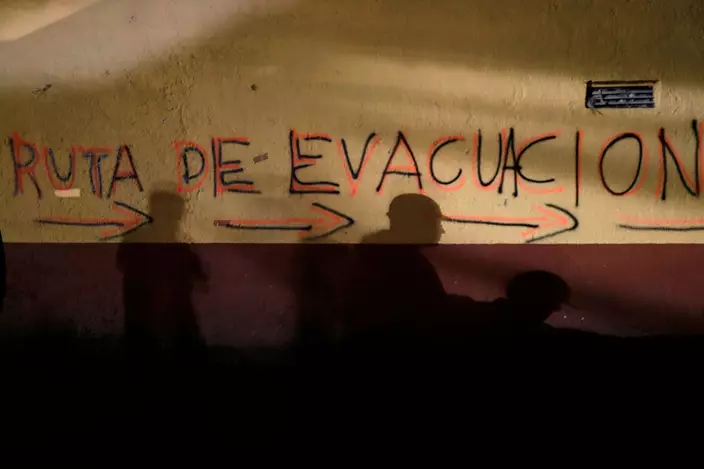

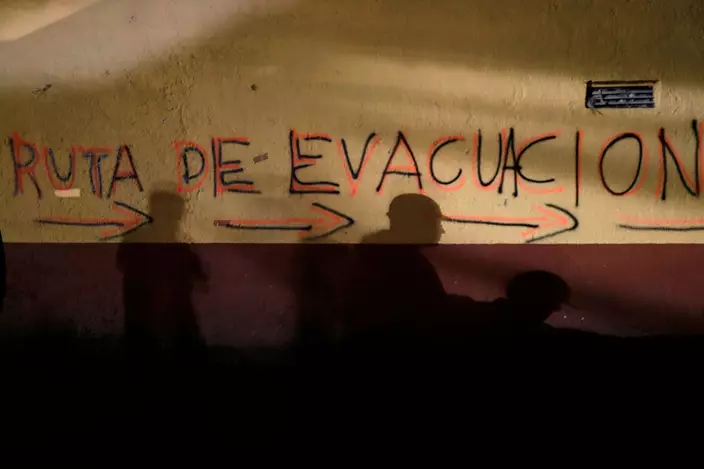

Shadows of rescue workers and volunteers are cast on the wall of an apartment building covered with the spray painted words in Spanish: "Evacuation route" in the southern neighborhood of Tlalpan in Mexico City, Monday, Sept. 25, 2017. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Dr. Misael Dominguez, an attending physician, said doctors have "practically everything we require."

"We have seen a lot of high blood pressure and sugar levels from the stress," he added.

At that moment, a doctor was poking one of Roberto Ramirez's fingers with a needle to draw blood and test his glucose levels. Ramirez, a 33-year-old musician and computer programmer, is a diabetic and lives in an apartment that has been deemed too dangerous to inhabit. He was away from home when the quake struck and wasn't able to retrieve his glucose testing kit.

He said he has been trying to take better care of his health since the quake, saying, "I value things more."

The result came back high: 259.

Lender Lopez, who had to evacuate his apartment, and his girlfriend Shaolin Duran prepare to spend the night at the Francisco Kino school, which was turned into a temporary shelter for residents evacuated from the large apartment complex in the Tlalpan neighborhood of Mexico City, Monday, Sept. 25, 2017. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

To the left of the entrance are signs offering psychological services. Many of those sheltering at the school have arrived with the quake's trauma still weighing heavily on their minds.

Florencia Cortes, 37, was pulled from the rubble of her apartment building along with her 20-month-old son, Jonatan. In order to get her son out, she had to swing him toward the building's plumber, who happened to be outside. He caught hold of the boy by his foot.

Jonatan used to follow his mother around everywhere. Now she says he stick by his father, who wasn't home during the quake.

"He's not the same," Cortes said. "Maybe he thinks I threw him and don't love him."

Many of the shelter residents harbor a deep mistrust of their government to set things right. While government workers occasionally come in, for the most part officials have been absent, they say. Some are vowing to stay until they're given a new place to call home.

"The government has the last word and no one knows anything about the government here," said Angelina Usuna, 81.

Marta Garcia gives a massage to a woman living inside the Francisco Kino school, which was turned into a temporary shelter for residents evacuated from a large apartment complex in the Tlalpan neighborhood of Mexico City, Monday, Sept. 25, 2017. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Night can bring the hardest hours. A lucky few have donated mattresses, but most are sleeping on uncomfortable foam mats. They get a few hours of sleep at best. Wary of sharing a collective space, no one feels entitled to tell someone else to be quiet or turn out a light.

In fact, it's impossible to make the gym completely dark. As part of the shelter's safety protocol, one light must be kept on in case another tremor strikes.

Juan Aldana plays with his son Jonatan while they live inside the Francisco Kino school, which was turned into a temporary shelter for residents evacuated from a large apartment complex in the Tlalpan neighborhood of Mexico City, Monday, Sept. 25, 2017. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

VILLA MADERO, Mexico (AP) — As a drought in Mexico drags on, angry subsistence farmers have begun taking direct action on thirsty avocado orchards and berry fields of commercial farms that are drying up streams in the mountains west of Mexico City.

Rivers and even whole lakes are disappearing in the once green and lush state of Michoacan, as the drought combines with a surge in the use of water for the country’s lucrative export crops, led by avocados.

In recent days, subsistence farmers and activists from the Michoacan town of Villa Madero organized teams to go into the mountains and rip out illegal water pumps and breach unlicensed irrigation holding ponds.

A potential conflict looms with avocado growers — who are often sponsored by, or pay protection money to, drug cartels.

Last week, dozens of residents, farmworkers and small-scale farmers from Villa Madero hiked up into the hills to tear out irrigation equipment using mountain springs to water avocado orchards carved out of the pine-covered hills.

The week before, another group went up with picks and shovels and breached the walls of an illegal containment pond that sucked up water from a spring that had supplied local residents for hundreds of years.

“In the last 10 years, the streams, the springs, the rivers have been drying up and the water has been captured, mainly to be used for avocados and berries,” said local activist Julio Santoyo, one of the organizers of the effort. “There are hamlets in the lower part of the township that no longer have water.”

Santoyo estimated that about 850 of the plastic-lined, earthen containment ponds have sprung up in the hills around Villa Madero, usually soon after planters have illegally logged or burned the native pine forest. Pines help the soil retain water, while avocado trees deplete it.

Francisco Gómez Cortés said residents of his hamlet, El Sauz, had been asking the landowner for 15 years to allow the spring to flow downhill to their community.

After a year in which Mexico received only about half its normal rainfall, residents became desperate, and last week they worked up the courage to hike up the hill and rip out pumps and hoses for the avocado orchard.

“We don't have enough water for human consumption,” Gómez Cortés said.

“It’s sad. It’s sad to walk down these trails that are now dry, when they once had trees and springs,” he said. “They haven’t even left any water for the (forest) animals that nest along the banks.”

In a sign of how seriously the local government is taking the potential threat, the group was accompanied by the mayor of Villa Madero, who blamed outsiders for the problem.

“There are people who aren't from this town, who come to our township and are invading us,” Mayor Froylan Alcauter Ibarra said. “They are taking water away from the people who live downhill, and they don't realize these are the poorest people.”

Residents say they don't want to deny water entirely to the orchards and have proposed an agreement to give landowners 20% of the water from local streams, if they allow the remaining 80% to keep flowing. They say they haven't gotten any response yet.

Drug cartels often make money from illegal logging and extorting money from avocado growers in Michoacan. The activists around Villa Madero have suffered threats, kidnappings and beatings in the past.

“We are running a serious risk of them killing us for protesting,” Gómez Cortés said. “Out of necessity, we are doing what the government should be doing.”

The government has long done little to limit the growers and combat deforestation and water takeovers. But it does seem to have developed a sudden interest in preventing the looming conflict.

In March, activists organized a meeting nearby at Patzcuaro Lake to demand authorities do something about the fast-declining water levels. Patzcuaro is a shallow but extensive lake in Michoacan with a beautiful colonial town on its shores and an island of fishermen perched in the middle.

The fishermen of Janitzio island with their shallow boats and hooped, figure-eight nets were made famous by photographers and filmmakers in the 1940s and 50s as a symbol of Mexico's folk traditions. The town of Patzcuaro draws hundreds of thousands of tourists.

But due to the drought, deforestation, sediment buildup and the increased water demands from avocado and berry growers, Patzcuaro lake has been reduced to about half its size. You can now reach the Janitzio island by wading, and activist Juan Manuel Valenzuela estimates that 90% of the boats that used to fish and ferry tourists around are now out of service.

Nearby Lake Cuitzeo, one of the largest freshwater lakes in Mexico, is now nearly dried up.

“We cannot allow them to extinguish our lakes,” Valenzuela said. “It would be a tragedy for Michoacan.”

Alejandro Méndez, Michoacan's state environment secretary, acknowledges that the problem has gotten out of hand. So scarce has water become in the once-lushly forested lake areas that orchard owners often send tanker trucks to suck thousands of gallons from the lake to water their groves.

“As many as 100 trucks could be seen taking water from the lake,” Méndez said of the situation in March.

So about a week ago, the state police began patrolling the lake shore and detaining any truck drivers they saw extracting water. And Méndez said the state has begun monitoring agricultural holding ponds to see if any are getting refilled from the lake.

While Lake Patzcuaro has grown and shrunk in the past, this time it may be terminal; farmers are starting to pasture livestock and plant crops on the lake bed.

“It will be difficult, because the humans and the livestock will survive, barely, but the animals and the plants will be gone — that will all be dried up and gone,” Gómez Cortés said.

AP writer Mark Stevenson in Mexico City contributed to this report.

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

Locals ride in a National Guard truck in search of unlicensed water intakes and irrigation holding ponds that irrigate avocado and berry orchards during a drought in the mountains of Villa Madero, Mexico, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. Subsistence farmers and activists from the Michoacan town of Villa Madero organized teams to go into the mountains and rip out illegal water pumps and breach unlicensed irrigation holding ponds. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

An unlicensed irrigation pond is under construction by an avocado orchard during a drought in the mountains of Villa Madero, Mexico, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. Farmers from Villa Madero who spotted the pond say they plan to meet with authorities to get the pond's owner to agree on a percentage of water usage, and if it fails, they plan to destroy it. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

A municipal police officer drinks water from a stream lined with an unlicensed hose as he accompanies locals who are dismantling illegal water taps during a drought in the mountains of Villa Madero, Mexico, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. On Wednesday, dozens of residents, farmworkers and small-scale farmers from Villa Madero hiked up into the hills to tear out irrigation equipment using mountain springs to water avocado orchards carved out of the pine-covered hills. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

Janitzio Island stands in Lake Patzcuaro, which has low water levels during a drought in Mexico, Thursday, April 18, 2024. Farmers are starting to pasture livestock and plant crops on the lake bed. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

Residents of Villa Madero look at unlicensed irrigation holding ponds during a drought in the mountains of Villa Madero, Mexico, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. The group said they plan to meet with authorities to get the pond's owner to agree on a percentage of water usage, and if it fails, they plan to destroy it. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

An armed police officer accompanies locals from Villa Madero through the mountains in search of unlicensed water intakes and irrigation ponds during a drought in Villa Madero, Mexico, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. Subsistence farmers and activists from the Michoacan town of Villa Madero organized teams to go into the mountains and rip out illegal water pumps and breach unlicensed irrigation holding ponds. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

A snail lays in the dry bed of Lake Patzcuaro, during a drought in Mexico, Thursday, April 18, 2024. The lake has been reduced to about half its size, due to drought, deforestation, sediment buildup, and increased water demands from avocado and berry growers. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

Boats are docked on the shore of Lake Patzcuaro, during a drought in Mexico, Thursday, April 18, 2024. Activist Juan Manuel Valenzuela estimates that 90% of the boats that used to fish and ferry tourists around are now out of service. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

People dismantle an unlicensed water intake as their group of residents, farmworkers and small-scale farmers disconnect water taps in the mountains of Villa Madero, Mexico, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. As Mexico's drought drags on, angry farmers in Villa Madero have begun taking direct action to dismantle illegal water intakes which they say are drying up the streams in the mountains west of Mexico City. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

An unlicensed irrigation pond holds water near an avocado orchard in the mountains of Villa Madero during a drought in Mexico, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. Residents from Villa Madero who spotted the pond say they plan to meet with authorities to get the pond's owner to agree on a percentage of water usage, and if it fails, they plan to destroy it. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)

A man shows a pump removed from an unlicensed water intake as his group of residents, farmworkers and small-scale farmers from Villa Madero dismantle illegal water taps in the mountains of Villa Madero, Mexico, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. As a drought in Mexico drags on, angry subsistence farmers have begun taking direct action on thirsty avocado orchards and berry fields of commercial farms that are drying up streams in the mountains west of Mexico City. (AP Photo/Armando Solis)