The last Leonardo da Vinci painting in private hands is going to auction in New York next month — with a pre-sale estimate of around $100 million.

Christie's announced Tuesday that the depiction of Jesus, titled "Salvator Mundi," will be offered Nov. 15.

Security guards open a door to reveal "Salvator Mundi" by Leonardo da Vinci during a news conference at Christie's in New York, Tuesday, Oct. 10, 2017. The piece, which was painted around 1500, is one of fewer than twenty da Vinci paintings known to exist. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

"The Salvator Mundi is the Holy Grail of Old Master paintings," declared Christie's specialist Alan Wintermute. "It seemed just a tantalizingly unobtainable dream until now. To see a fully finished, late masterpiece by Leonardo, made at the peak of his genius, appear for sale in 2017 is as close as I've come to an art world miracle."

The work, dating from around 1500, is one of fewer than 20 known paintings by Leonardo. It was first recorded in the royal collection of King Charles I in the early 1600s, then changed hands, dropped out of sight and was later acquired "as a work by Leonardo's follower," Christie's said. "Christ's face and hair were overpainted."

Security guards set up a rope in front of "Salvator Mundi" by Leonardo da Vinci during a news conference at Christie's in New York, Tuesday, Oct. 10, 2017. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

It was sold for 45 British pounds in 1958, Christie's said.

It disappeared again for nearly half a century; it was believed that the work had been destroyed until it was rediscovered in 2005. It took six years to authenticate it.

Christie's said it decided to highlight the Leonardo at a sale of post-war and contemporary art because "this work and artist transcend all collecting categories."

The seller is identified only as a "private European collection."

A security guards stands near "Salvator Mundi" by Leonardo da Vinci during a news conference at Christie's in New York, Tuesday, Oct. 10, 2017. The piece, which was painted around 1500, is one of fewer than twenty da Vinci paintings known to exist. After public exhibitions around the world, the auction is scheduled to take place on Nov. 15, 2017. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Andy Warhol's 1986 painting "Sixty Last Suppers" — based on Leonardo's Renaissance "Last Supper" masterpiece — also will be featured. Its estimate is around $50 million.

Warhol's "monumental canvas poignantly illustrates the themes of religion and loss that were so instrumental to his work," the auction house said.

The work was executed a year before the artist's death.

"In the early 1980s, religious iconography would feature more prominently in Warhol's art as he began to confront his mortality," Christie's said. "'Sixty Last Suppers' marked the culmination of a process of acceptance: the final image of communion and forgiveness."

HAVANA (AP) — His novels recount gruesome murders, thefts, scams, bribes and humiliating secrets. But those are not even the most important themes in the stories told by award-winning Cuban writer Leonardo Padura.

For the last four decades, Padura, 68, has managed to turn his series of detective thrillers into a social and political chronicle of Cuba, especially Havana, where he has lived all his life.

The island he depicts in his books — which have been translated to dozens of languages — is a mix of economic deprivation, Afro-descendant syncretism, corruption, mischief, uplifting music and growing inequality — all seasoned by a revolution that marked the 20th century.

“I write about the problems of individuals in Cuban society. And often, in my books, more than dramatic conflicts between the characters, you will find a social conflict between the characters and their historical time,” Padura told The Associated Press in a recent interview at his home in Mantilla, the populous Havana neighborhood where he was born, raised and married.

The scent of freshly brewed coffee is in the air, as well as the chirping sound of the birds that inhabit the patio where his dogs are buried. In a nearby studio, his wife, screenwriter Lucía López Coll, works on a computer.

It's also in this house where Mario Conde, the principal character of Padura’s work, was born. The downtrodden, nostalgic, chain-smoking detective has accompanied Padura since 1991, when “Past Perfect” — the first of the “Havana Quartet” series featuring Conde as the main protagonist — was published.

Keeping track of Detective Conde is almost like taking the pulse of Cuba in the last few years.

His last appearance was in the 2020 novel “Personas Decentes” ("Decent People") in which, now over 60 years old, Conde gets involved in the investigation of a homicide — and corruption case — against the backdrop of the 2016 historic visit of former U.S. President Barack Obama and the Rolling Stones to the island.

“This character comes from a neighborhood similar to mine,” Padura says of Conde. “He is a man of my generation. ... His view of reality has evolved because I have evolved, and his feeling of disenchantment has a lot to do with the way we have been living all these years.”

Reflecting on Cuba’s situation after the tightening of U.S. sanctions during the administration of President Donald Trump and the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, Padura says the island has barely crawled out of the crisis and has not yet been able to get back on its feet.

He points at the lack of food and medications, rising prices and deteriorating health and education systems, while Cubans grapple with fuel shortages and constant blackouts.

“There is a historical fatigue," he says. "People are tired, they have no alternatives and they look for one by emigrating.”

The soft-spoken chronicler highlights yet another impact of Cuba's ongoing economic crisis: A wave of popular protests and demonstrations that had not been seen in decades.

“The main cry was for food and electricity,” Padura recalls about the protests in 2021 and, more recently, in March. “But people also screamed ‘Freedom!' The lack of food and electricity might have been solved by fixing some thermoelectric plants and with a little rice and sugar ... but the other thing has not been talked about — and I think it's something that should be discussed in depth.”

Born in 1955, Leonardo de la Caridad Padura Fuentes studied literature at the University of Havana and worked as a journalist for state-owned media in the 1980s.

He has won a number of important prizes, including the Hammett Prize, awarded by the International Association of Crime Writers, on two occasions (1998 and 2006); Cuba's National Prize for Literature In 2012, and the Princess of Asturias Award for literature in Spain in 2015.

In 2016, Netflix released “Four Seasons in Havana,” a miniseries featuring detective Conde.

Despite the international recognition, only a few of Padura's books have been published in Cuba, and when they do, only a few copies are printed. Also, because of his critical, sometimes dark view of the island, his work is barely promoted or mentioned in the official media.

Unlike many writers and intellectuals who in recent years decided to leave Cuba, Padura — who travels extensively — is determined to stay.

“I have many reasons for living outside of Cuba but I think the ones that keep me here weigh more heavily. One of them is my sense of belonging," he says. "I have a strong sense of belonging to a reality, to a culture, to a way of seeing life, to a way of expressing myself.”

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

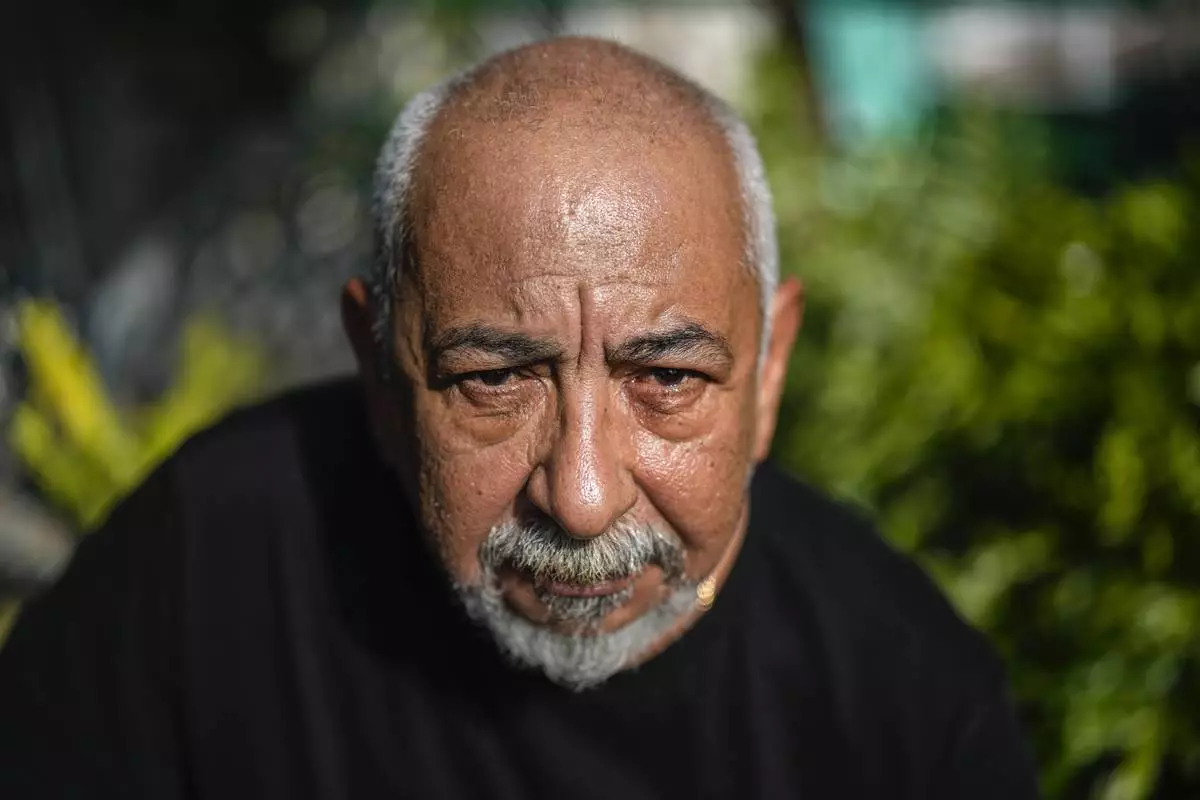

Cuban writer Leonardo Padura gives an interview at his home in Havana, Cuba, Wednesday, April 10, 2024. Padura has managed to turn his series of detective novels into a social and political chronicle of Cuba, especially his native Havana. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

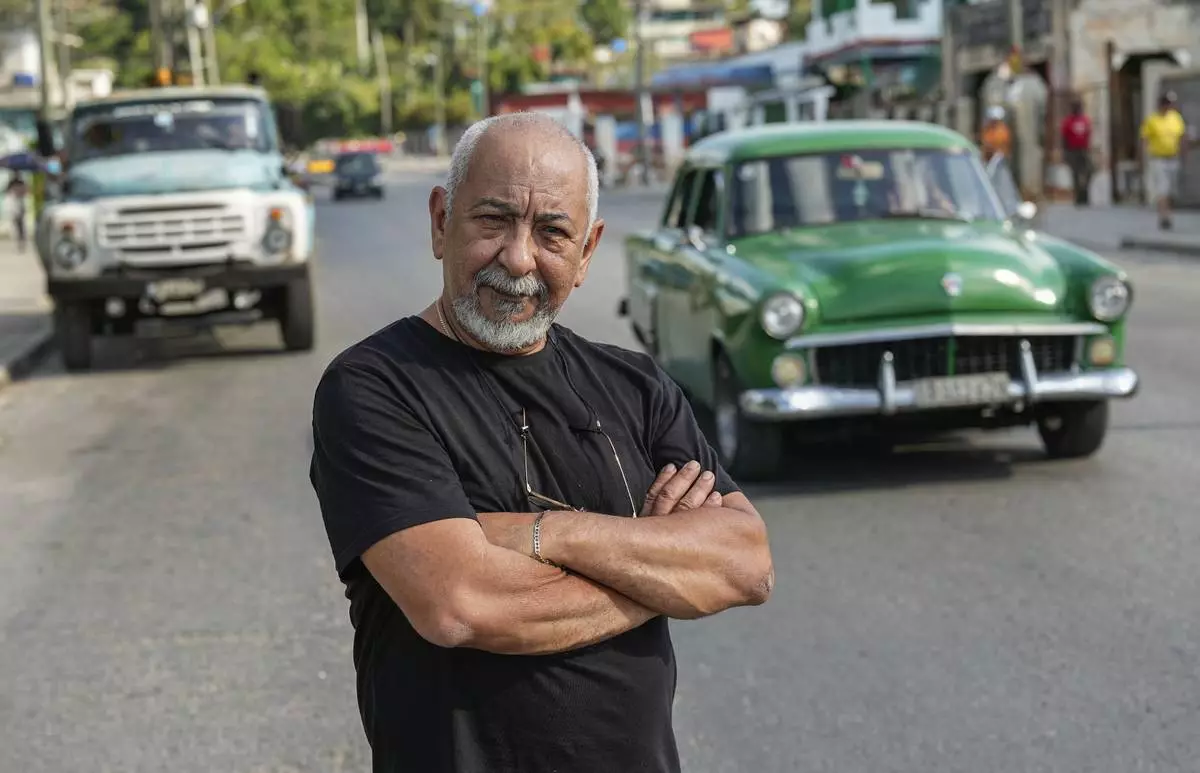

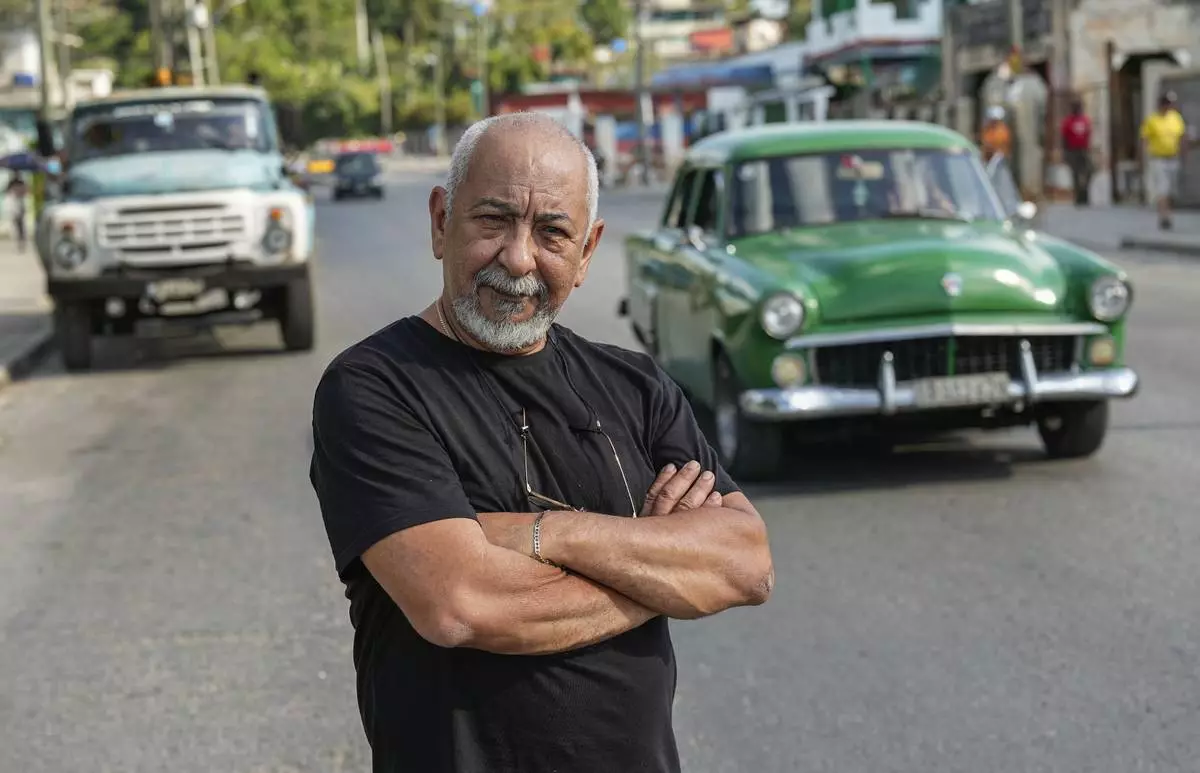

Cuban writer Leonardo Padura poses for a portrait in the street in Havana, Cuba, Wednesday, April 10, 2024. Padura has managed to turn his series of detective novels into a social and political chronicle of Cuba, especially his native Havana. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

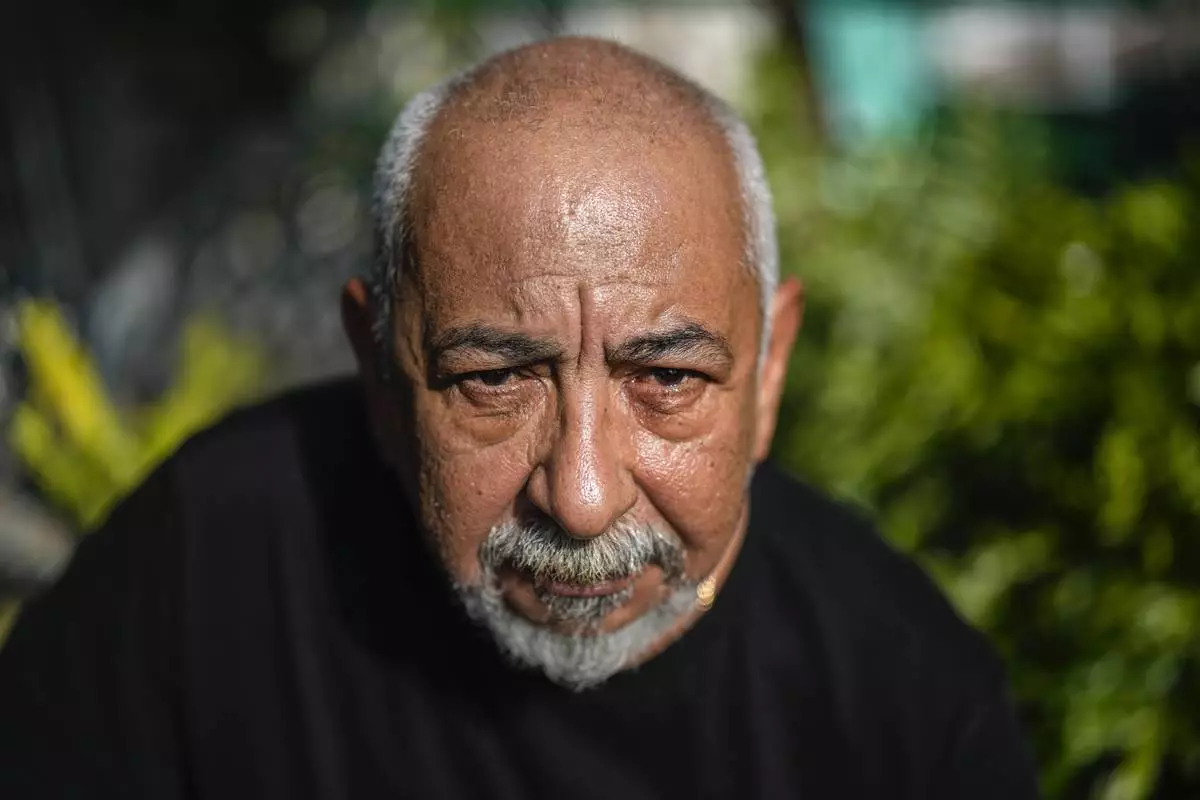

Cuban writer Leonardo Padura poses for a portrait at his home in Havana, Cuba, Wednesday, April 10, 2024. Padura has managed to turn his series of detective novels into a social and political chronicle of Cuba, especially his native Havana. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)