Lebanon-based businessmen who lost enterprises through dealings with members of Saudi Arabia's royal family and others in the kingdom are closely watching a new campaign led by the powerful crown prince targeting officials, princes and tycoons in the oil-rich kingdom, hoping it will help them win back what they lost over the years.

The campaign, which Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman says is aimed at cracking down on corruption in the kingdom, has been met with skepticism by many. With dozens of powerful princes, business leaders and government officials in custody, the move has provoked speculation the crackdown is more about consolidating power than curbing corruption. Others speculate the move amounts to a shake-down of wealthy players for their assets as the crown prince tries to implement sensitive economic reforms in the face of lower oil prices.

Click to Gallery

Lebanon-based businessmen who lost enterprises through dealings with members of Saudi Arabia's royal family and others in the kingdom are closely watching a new campaign led by the powerful crown prince targeting officials, princes and tycoons in the oil-rich kingdom, hoping it will help them win back what they lost over the years.

Either way, many in the kingdom welcome efforts to fight rampant corruption and abuse of power, and many outside it hope the move will encourage people to invest in the kingdom without fear.

Their court battles are over Lebanon's leading LBC and the affiliated Production and Acquisition Company, widely known as PAC, which filed for liquidation in 2012. Some 400 PAC employees lost their jobs and are still waiting for Prince Alwaleed to compensate them.

Morcos added that the prosecution that is done in Saudi Arabia does not directly affect a prosecution taking place in Lebanon.

Khader added that the first step by MBS is to fight corruption and people in the kingdom have been waiting for an "awakening against corruption." Khader said "Saudi Arabia has all the capabilities to become one of the most important countries in the world If we can fight corruption and it will not be an easy mission but we are very optimistic about what happened."

FILE - In this file picture taken May 14, 2012, Saudi Arabia's Interior Minister Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, left, his older brother Saud bin Nayef, center, Prince Miteb bin Abdullah, son of Saudi King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz al-Saud wait for Gulf Arab leaders ahead of the opening of Gulf Cooperation Council, also known as GCC summit, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. (AP Photo/Hassan Ammar, File)

Either way, many in the kingdom welcome efforts to fight rampant corruption and abuse of power, and many outside it hope the move will encourage people to invest in the kingdom without fear.

Since the first week of November, some 201 people have been taken into custody by Saudi authorities in a sweep that investigators say has uncovered at least $100 billion in corruption. The detainees include Cabinet ministers, members of the royal family and the owners of three TV networks that are among the largest in the Middle East.

The crackdown that began on Nov. 4 initially targeted 11 princes, 38 officials, military officers as well as business leaders. An estimated 1,700 individual bank accounts have been frozen.

Saudi critics and experts have called the unprecedented purge of top princes and businessmen by the crown prince, also known by his initials MBS, a bold and risky move aimed at consolidating power as he keeps an eye on the throne, sidelining potential rivals and dismantling alliances built with other branches of the royal family.

Pierre Daher, who founded the first private TV station in Lebanon in 1985 and turned it into one of the top media outlets in the Arab world, has been locked in court cases with detained Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, one of the world's richest men, since 2011. The prince, whose maternal grandfather Riad Solh was once Lebanon's prime minister and also holds Lebanese citizenship, has investments that include Twitter, Apple, Citigroup and the Four Seasons hotel chain and was once a significant shareholder in Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation, but sold much of those shares in 2015.

FILE - In this file picture taken May 14, 2012, Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) speaks with a Saudi prince while he waits for Gulf Arab leaders ahead of the opening of Gulf Cooperation Council summit, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. (AP Photo/Hassan Ammar, File)

Their court battles are over Lebanon's leading LBC and the affiliated Production and Acquisition Company, widely known as PAC, which filed for liquidation in 2012. Some 400 PAC employees lost their jobs and are still waiting for Prince Alwaleed to compensate them.

Prince Alwaleed and Daher, now chairman and CEO of LBC, were once allies when the prince pumped money into LBC TV before the two split over several issues and Daher was removed from his job as head of PAC. Prince Alwaleed ended up taking over the LBC SAT and PAC while Daher took LBC.

"The disgraceful behavior of Alwaleed by making the company (PAC) bankrupt fraudulently while it was not bankrupt and had assets. PAC was able to continue normally but he mechanically made up bankruptcy," said Daher in his LBC office in the posh town of Adma north of Beirut.

Several cases between the two are still ongoing in countries including Lebanon, Britain and the Cayman Islands. Daher says that he is suing Prince Alwaleed for more than $100 million and is optimistic he will win.

Lebanese media outlets reported this month that two Beirut hotels owned by Prince Alwaleed's Kingdom Holding are for sale. The Four Seasons and Mövenpick Hotel are among Beirut's most luxurious hotels and are located in two of the capital's most posh neighborhoods.

"If the hotels are not in the person's name, not in the name of the defendant himself in person, you cannot garnish them since they belong to a company," said Paul Morcos, legal expert and founder and owner of Justicia Consulting Law firm in Beirut.

In this picture taken Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2017, a general view shows the master control room at the LBC TV station in Beirut, Lebanon.(AP Photo/Hassan Ammar)

Morcos added that the prosecution that is done in Saudi Arabia does not directly affect a prosecution taking place in Lebanon.

Attempts to reach a representative of Prince Alwaleed at Kingdom Holding were not immediately successful.

Another person who lost millions of dollars in the kingdom as a result of alleged corruption is Lebanon-based U.S. citizen Yahya Lotfi Khader who for more than 20 years ran petrochemical businesses along with his two partners in eastern Saudi Arabia.

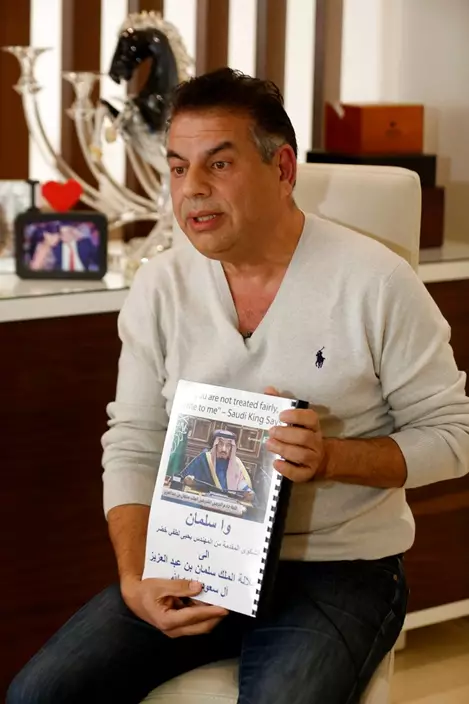

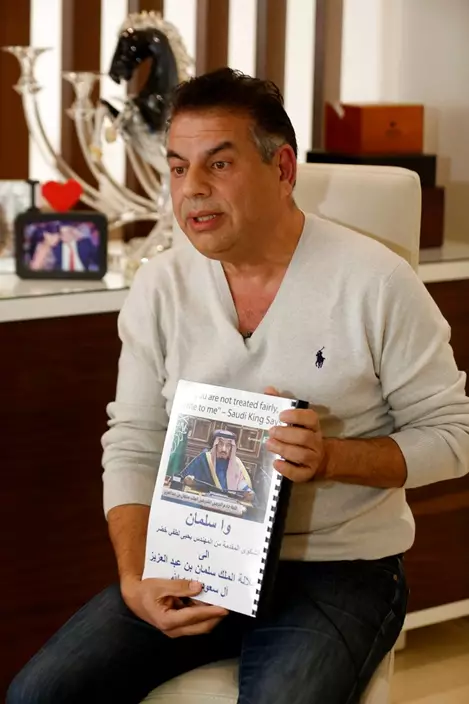

The Syria-born, 57-year-old businessman said he left the kingdom two years ago after he became the victim of interference by officials who worked in the office of a once powerful prince, Saoud bin Nayef, the brother of the former crown prince who was removed from his post earlier this year. Khader put forward documents that proves they have lost tens of millions of dollars in cases that he says were manipulated by powerful people in the kingdom.

"There is widespread corruption from princes to ministers to judges to lawyers to businessmen," Khader said, speaking in his posh apartment overlooking the Mediterranean Sea in the north Beirut suburb of Dbayeh. "Regrettably there are people who are taking advantage of the wealth and powers of the kingdom and are taking it in the wrong direction."

In this picture taken Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2017, a Lebanese flag waves in front the Four Seasons in Beirut, Lebanon. (AP Photo/Hassan Ammar)

Khader added that the first step by MBS is to fight corruption and people in the kingdom have been waiting for an "awakening against corruption." Khader said "Saudi Arabia has all the capabilities to become one of the most important countries in the world If we can fight corruption and it will not be an easy mission but we are very optimistic about what happened."

Khader has sent documents listing all the injustice they were subjected to in the kingdom to the office of King Salman and MBS hoping that it could help them return to the kingdom and get back their money that are worth tens of millions of dollars.

"What is happening in Saudi Arabia is a game changer. It is turning the country on the political, economic, social and religious levels," said Daher of LBC.

He added: "Today there is a new Saudi Arabia that is totally different from what it used to be but it is still early to judge it."

In this picture taken Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2017, Lebanon-based U.S. citizen Yahya Lotfi Khader shows documents during an interview with Associated Press in Beirut, Lebanon.(AP Photo/Hassan Ammar)

KARACHI, Pakistan (AP) — Born and raised in Pakistan to parents who fled neighboring Afghanistan half a century ago, an 18-year-old found himself at the mercy of police in Karachi who took his cash, phone and motorbike, and sent him to a deportation center.

Scared and bewildered, he spent three days there before he was sent back to Afghanistan, a place he has never been to, with nothing but clothes on his back.

The youth is one of at least 1.7 million Afghans who made Pakistan their home as their country sank deeper into decades of war. But they've been living there without legal permission, and are now the target of a harsh crackdown on migrants who Pakistan says must leave.

Some 600,000 Afghans have returned home since last October, when the crackdown began, meaning at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They’ve retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next for deportation.

It’s harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis.

The youth, who had been working as a mechanic in an auto shop since he was 15, spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of arrest and deportation.

He has applied for the same documentation that his family has, but he won’t get it. Pakistan isn’t issuing paperwork for Afghan refugees or their children.

“My life is here. I have no friends or family in Afghanistan, nothing,” the young man told The Associated Press. “I wanted to come back (to Pakistan) sooner, but things had to calm down first,” he said, referring to the anti-migrant raids sweeping the country at the time.

Taliban authorities gave him 2,500 afghanis ($34) once he entered Afghanistan to start a new life. They dispatched him to northeastern Takhar province, where he slept in mosques and religious schools because he knew nobody to stay with. He passed his time playing cricket and football, and borrowed other people’s phones to call his family.

Six weeks later, he traveled from Takhar to the Afghan capital, Kabul, then to eastern Nangarhar province. He walked for hours in the dark before meeting up with human smugglers hired by his brother in Pakistan. Their job was to get him to Peshawar, the capital of Pakistan’s northwest Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, for the price of $70.

He is relieved to be reunited with his family. But he is vulnerable.

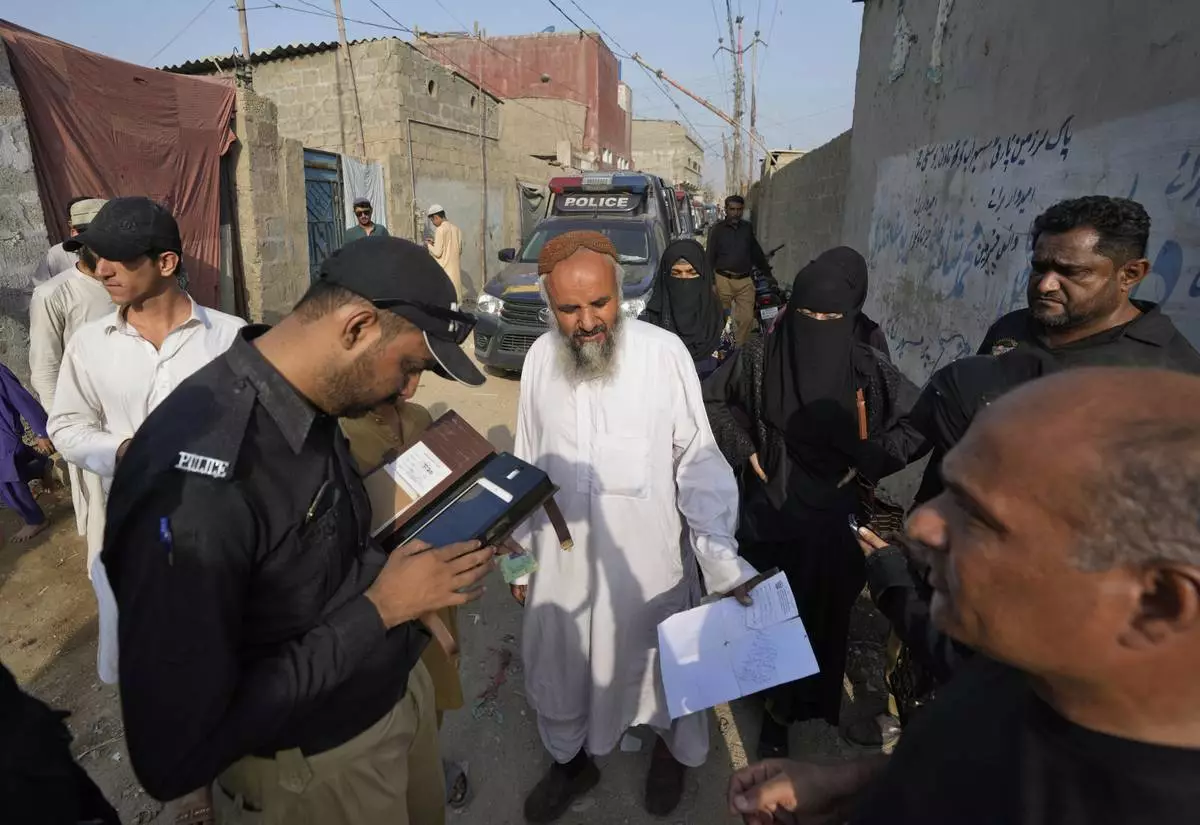

Police have daubed numbers on homes in his neighborhood to show how many people live there and how many have documentation. Hundreds of Afghan families have fled the area since the operation began. There are fewer people to hide among.

Such neighborhoods in Karachi are easily home to tens of thousands of Afghans. But they have no drainage systems, health care or education facilities. There are few women on the streets, and those who venture out wear burqas, often the blue ones more commonly seen in Afghanistan.

Lawyer Moniza Kakar, who works extensively with the Afghan community in Karachi, said there are generations of families with no paperwork. Without it, they can't access basic services like schools or hospitals.

Afghans were already under the radar before the crackdown, and rumours abound that Pakistan wants to expel all Afghans, even those with documentation. Pakistan says no such decision has been made.

In another Karachi neighborhood with a mostly Afghan population, people scatter when police arrive, disappearing into a maze of alleys. A network of informants spread news of the visits.

Kakar despairs at the plight of Afghans who remain in Pakistan. “Sometimes they don’t have food so we appeal to the U.N. to help them out,” she said. To earn money or get medical help, they would have previously traveled from such neighborhoods into the heart of Karachi, but they can’t afford these journeys anymore. They’re also likely to be arrested, she added.

Some show Kakar their ID cards from the time of Gen. Zia Ul-Haq, the military dictator whose rule of Pakistan coincided with the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. “They wonder why they don’t have citizenship after 40 years. They don’t share their location. They don’t go out. They live in property rented in someone else’s name.”

There are children who were born in Pakistan who have grown up and have children of their own. “The children don’t have any identity paperwork. All of them have an undecided future,” said Kakar.

Syed Habib Ur Rehman works as a media coordinator at the Afghanistan Consulate General in Karachi. He spends a lot of time in these communities.

“There are empty homes, empty shops,” Rehman said. “Markets are empty. The Pakistanis we know don’t agree with what is happening. They say they have spent a good life with us. Their business has gone down because so many Afghan families have left.”

The Afghans interviewed by the AP had different reasons for never securing their status. Some said they were overseas working. Others didn’t have time. Nobody thought Pakistan would ever throw them out.

Mohammad Khan Mughal, 32, was born in Karachi and has three children. Before the crackdown started, the Afghan ran a tandoor business. Police told him to close down.

“My customers started complaining because they couldn’t buy bread from me,” he said. He and his family went to the southwestern city of Quetta in Baluchistan province to escape the raids.

He returned to Karachi a few days later, and has no intention of leaving.

“This is my home,” he said, with pride and sadness. “This is my city.”

Follow AP's global migration coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/migration

Children play on a street in a neighbourhood, where mostly Afghan populations, in Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Jan. 26, 2024. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)

Burqa-clad Afghan women walk on a street in a a neighbourhood, where mostly Afghan populations, in Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Jan. 26, 2024. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)

Burqa-clad Afghan women walk on a street with other in a a neighbourhood, where mostly Afghan populations, in Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Jan. 26, 2024. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)

A worker prepare 'Naan' at a ran locally called 'Tandoor' in a a neighbourhood, where mostly Afghan populations, in Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Jan. 26, 2024. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)

People walk on a street in a a neighbourhood, where mostly Afghan populations, in Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Jan. 26, 2024. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)

FILE - An Afghan boy sits over his family's belongings retrieved from their damaged mud homes demolished by authorities during a crackdown against an illegal settlement and immigrants, on the outskirts of Islamabad, Pakistan, Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2023. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Anjum Naveed, File)

FILE - Afghan families board a bus to depart for their homeland, in Karachi, Pakistan, Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2023. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan, File)

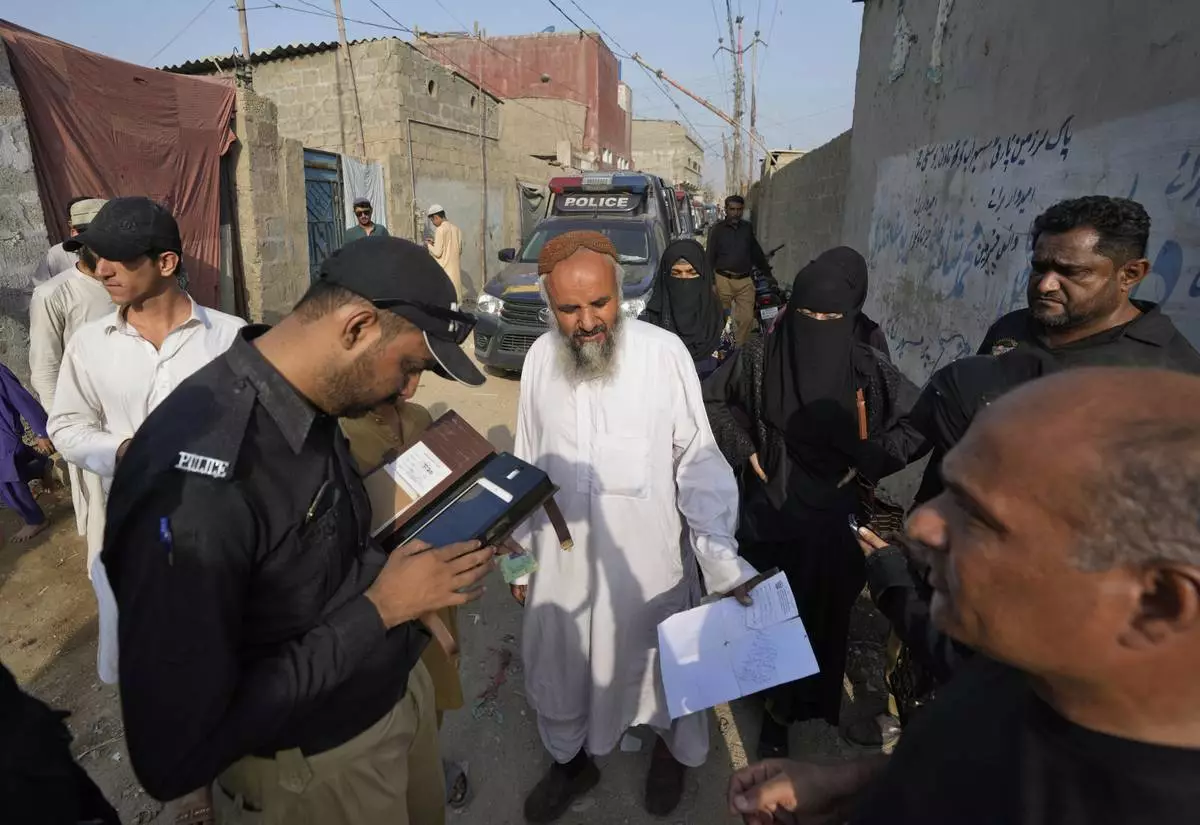

FILE - A police officer checks the document of a resident during a search operation against illegal immigrants at a neighborhood of Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Nov. 3, 2023. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan, File)

FILE - A convey of trucks carrying Afghan families drive toward a border crossing point in Torkham, Pakistan, Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2023. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis. (AP Photo/Muhammad Sajjad, File)

FILE - Afghan families onboard a truck head toward a border crossing point in Torkham, Pakistan, Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2023. For more than 1 million Afghans who fled war and poverty to Pakistan, these are uncertain times. Since Pakistan announced a crackdown on migrants last year, some 600,000 have been deported and at least a million remain in Pakistan in hiding. They've retreated from public view, abandoning their jobs and rarely leaving their neighborhoods out of fear they could be next. It's harder for them to earn money, rent accommodation, buy food or get medical help because they run the risk of getting caught by police or being reported to authorities by Pakistanis.(AP Photo/Muhammad Sajjad, File)

An 18-year-old Afghan boy, who asked not to use his name and not to show his face fearing his identity could lead to his capture again, pose for photograph behind a window during an interview with The Associated Press, in Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Jan. 26, 2024. Born and raised in Pakistan to parents who fled neighboring Afghanistan half a century ago, an 18-year-old found himself at the mercy of police in Karachi who took his cash, phone and motorbike, and sent him to a deportation center. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)

An 18-year-old Afghan boy, who asked not to use his name and not to show his face fearing his identity could lead to his capture again, pose for photograph behind a window during an interview with The Associated Press, in Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Jan. 26, 2024. Born and raised in Pakistan to parents who fled neighboring Afghanistan half a century ago, an 18-year-old found himself at the mercy of police in Karachi who took his cash, phone and motorbike, and sent him to a deportation center. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)

An 18-year-old Afghan boy, who asked not to use his name and not to show his face fearing his identity could lead to his capture again, pose for photograph during an interview with The Associated Press, in Karachi, Pakistan, Friday, Jan. 26, 2024. Born and raised in Pakistan to parents who fled neighboring Afghanistan half a century ago, an 18-year-old found himself at the mercy of police in Karachi who took his cash, phone and motorbike, and sent him to a deportation center. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)