It's been 22 years since Bosnia's bloody 1992-95 war ended, yet the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes still await identification.

Forensic anthropologist Dragana Vucetic spends her working hours in a forensic facility in the northern town of Tuzla collecting DNA samples from the bones of people killed in eastern Bosnia during the war, including in the notorious 1995 Srebrenica massacre, and reassembling their skeletal remains.

Click to Gallery

It's been 22 years since Bosnia's bloody 1992-95 war ended, yet the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes still await identification.

A U.N court will hand down its verdict Wednesday in the case against Ratko Mladic, who led Bosnian Serb forces in their quest to dismember Bosnia, carve out an "ethnically pure" Serb territory and unite it with neighboring Serbia. Mladic was on the ground with his troops when they overran Srebrenica in July 1995 and proceeded to hunt down and slaughter around 8,000 Muslim Bosnian men and boys. He was charged with genocide for his role in the massacre.

When the search for the war missing began, it wasn't unusual for the remains of one Srebrenica victim to be found scattered between several different mass graves, sometimes miles apart.

In this Monday, Nov. 6, 2017, photo, forensic anthropologist Dragana Vucetic handles human bones before collecting DNA samples of people killed in eastern Bosnia during the war, at a forensic facility in Tuzla, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification.(AP Photo/Amel Emric)

In this Monday, Nov. 6, 2017, photo, forensic anthropologist Dragana Vucetic handles human bones before collecting DNA samples of people killed in eastern Bosnia during the war, at a forensic facility in Tuzla, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

In this Thursday, Nov. 16, 2017, photo, a woman touches grave stones at the memorial center of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

In this Monday, Nov. 6, 2017, photo, forensic anthropologist Dragana Vucetic handles human bones before collecting DNA samples of people killed in eastern Bosnia during the war, at a forensic facility in Tuzla, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

In this Thursday, Nov. 16, 2017, photo, a woman gestures near grave stones at the memorial centre of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

FILE - In this Tuesday, May 26, 2009, file photo, Bosnian forensic pathologist Vedo Tuco stands next to human remains found in a mass grave in the village of Mrsici, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric, File)

In this Thursday, Nov. 16, 2017, aerial photo, grave stones line in rows at the memorial center of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

FILE - In this Thursday, July 25, 2002, file picture, a group of Bosnian Muslim villagers look at the remains of bodies exhumed from a mass grave in the village of Kamenica, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric, File)

A U.N court will hand down its verdict Wednesday in the case against Ratko Mladic, who led Bosnian Serb forces in their quest to dismember Bosnia, carve out an "ethnically pure" Serb territory and unite it with neighboring Serbia. Mladic was on the ground with his troops when they overran Srebrenica in July 1995 and proceeded to hunt down and slaughter around 8,000 Muslim Bosnian men and boys. He was charged with genocide for his role in the massacre.

Throughout the war, Serb soldiers had been throwing their victims' bodies in mass graves. In Srebrenica, they first dumped them in several large pits and then moved them with trucks and bulldozers to over 90 smaller clandestine mass burial sites attempting to hide the massacre.

FILE- In this Tuesday, April 2, 1996, file photo, the remains of two bodies and pieces of clothing lie in a field at a suspected mass grave site in the village of Konjevic Polje, approximately 20km (12 miles), north west of Srebrenica. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda, File)

When the search for the war missing began, it wasn't unusual for the remains of one Srebrenica victim to be found scattered between several different mass graves, sometimes miles apart.

Vucetic's employer, the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), has pioneered a DNA-based system to identify the remains. Through their efforts, over 70 percent of the estimated 30,000 persons missing from the Bosnian war have so far been accounted for. The figure includes nearly 7,000, or almost 90 percent, of the victims of Srebrenica.

EDS NOTE: GRAPHIC CONTENT FILE - In In this, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2013, file photo, Bosnian technical worker Zlatan Music examines bodies exhumed from a mass grave at the Sejkovaca identification center, near Sanski Most, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric, File)

In this Monday, Nov. 6, 2017, photo, forensic anthropologist Dragana Vucetic handles human bones before collecting DNA samples of people killed in eastern Bosnia during the war, at a forensic facility in Tuzla, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification.(AP Photo/Amel Emric)

In this Monday, Nov. 6, 2017, photo, forensic anthropologist Dragana Vucetic handles human bones before collecting DNA samples of people killed in eastern Bosnia during the war, at a forensic facility in Tuzla, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

In this Thursday, Nov. 16, 2017, photo, a woman touches grave stones at the memorial center of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

In this Monday, Nov. 6, 2017, photo, forensic anthropologist Dragana Vucetic handles human bones before collecting DNA samples of people killed in eastern Bosnia during the war, at a forensic facility in Tuzla, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

In this Thursday, Nov. 16, 2017, photo, a woman gestures near grave stones at the memorial centre of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

FILE - In this Tuesday, May 26, 2009, file photo, Bosnian forensic pathologist Vedo Tuco stands next to human remains found in a mass grave in the village of Mrsici, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric, File)

In this Thursday, Nov. 16, 2017, aerial photo, grave stones line in rows at the memorial center of Potocari near Srebrenica, Bosnia. As a U.N court prepares to hand down its verdict in the case against Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military leader during the Balkan country's 1992-5 war, the remains of numerous victims of genocide and war crimes of which he stands accused still await identification. (AP Photo/Amel Emric)

HELENA, Mont. (AP) — BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of an asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program.

Attorneys for the company say the corporate predecessors of the railroad, owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate, didn't know the vermiculite they hauled over decades from a nearby mine was filled with hazardous microscopic asbestos fibers.

The case in federal civil court over the two deaths is the first of numerous lawsuits against the Texas-based railroad corporation to reach trial over its past operations in Libby, Montana. Current and former residents of the small town near the U.S.-Canada border want BNSF held accountable for its alleged role in asbestos exposure that health officials say has killed several hundred people and sickened thousands.

Looming over the proceedings is W.R. Grace & Co., a chemical company that operated a mountaintop vermiculite mine 7 miles (11 kilometers) outside of Libby until it was closed 1990. The Maryland-based company played a central role in Libby's tragedy and has paid significant settlements to victims.

U.S. District Court Judge Brian Morris has referred to the the chemical company as “the elephant in the room” in the BNSF trial. He reminded jurors several times that the case was about the railroad's conduct, not W.R. Grace's separate liability.

Federal prosecutors in 2005 indicted W. R. Grace and executives from the company on criminal charges over the contamination in Libby. A jury acquitted them following a 2009 trial.

How much W.R. Grace revealed about the asbestos dangers to Texas-based BNSF and its corporate predecessors has been sharply disputed.

The railroad said it was obliged under law to ship the vermiculite, which was used in insulation and for other commercial purposes, and that W.R. Grace employees had concealed the health hazards from the railroad.

Former railroad workers said during testimony and in depositions that they knew nothing about the risks of asbestos. They said Grace employees were responsible for loading the hopper cars, plugging the holes of any cars leaking vermiculite and occasionally cleaned up material that spilled in the rail yard.

Former rail yard worker John Swing said in previously recorded testimony that he didn’t know asbestos was an issue in Libby until a 1999 newspaper story reporting deaths and illnesses among mine workers and their families.

Swing also said he didn’t think the rail yard was dusty. His testimony was at odds with people who grew up in Libby and recall dust getting kicked up whenever the wind blew or a train rolled through the yard.

The estates of the two deceased plaintiffs have argued that the W.R. Grace’s actions don’t absolve BNSF of its responsibility for knowingly exposing people to asbestos at its railyard in the heart of the community.

Their attorneys said BNSF should have known about the dangers because Grace put signs on rail cars carrying vermiculite warning of potential health risks. They showed jurors an image of a warning label allegedly attached to rail cars in the late 1970s that advised against inhaling the asbestos dust because it could cause bodily harm.

BNSF higher-ups also should have been aware of the dangers because they attended conferences that discussed dust diseases like asbestosis in the 1930s, attorneys for the plaintiffs argued.

Family members of Tom Wells and Joyce Walder testified that their lives ended soon after they were diagnosed with mesothelioma. The families said the dust blowing from the rail yard sickened and killed them.

In a March 2020 video of Wells played for jurors and recorded the day before he died, he lay in a home hospital bed, struggling to breathe.

“I’ve been placed in a horrible spot here, and the best chance I see at release — relief for everybody — is to just get it over with,” he said. “It’s just not something I want to try and play hero through because I don’t think that there’s a miracle waiting.”

The Environmental Protection Agency descended on Libby after the 1999 news reports. In 2009 it declared in Libby the nation’s first ever public health emergency under the federal Superfund cleanup program.

The pollution in Libby has been cleaned up, largely at public expense. Yet the long timeframe over which asbestos-related diseases develop means people previously exposed are likely to continue getting sick for years to come, health officials say.

Judge Morris on Thursday rejected the railroad’s requests for verdicts in its favor before the case reached the jury.

BNSF attorneys asserted it was not liable in Libby because the railroad's duties as a “common carrier” of goods shielded it from some legal claims.

But Morris said the plaintiffs offered sufficient evidence that the railroad’s actions fell outside those legal protections because it conducted “abnormally dangerous activity” by maintaining a railyard with asbestos that could go airborne and spread into Libby.

The judge cited last year’s derailment and fire of a Norfolk Southern train carrying chemicals through East Palestine, Ohio. A court found that some of the railroad's actions in East Palestine weren't shielded by the law because it voluntarily blew open cars and burned the chemicals after the derailment so that it could resume running trains.

Morris said BNSF's actions likewise were not shielded because it was not bound by public duties to maintain the rail yard as it did.

Brown reported from Billings, Montana.

FILE - Environmental cleanup specialists work at one of the last remaining residential asbestos cleanup sites in Libby, Montana, in mid-September. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (Kurt Wilson/The Missoulian via AP, File)

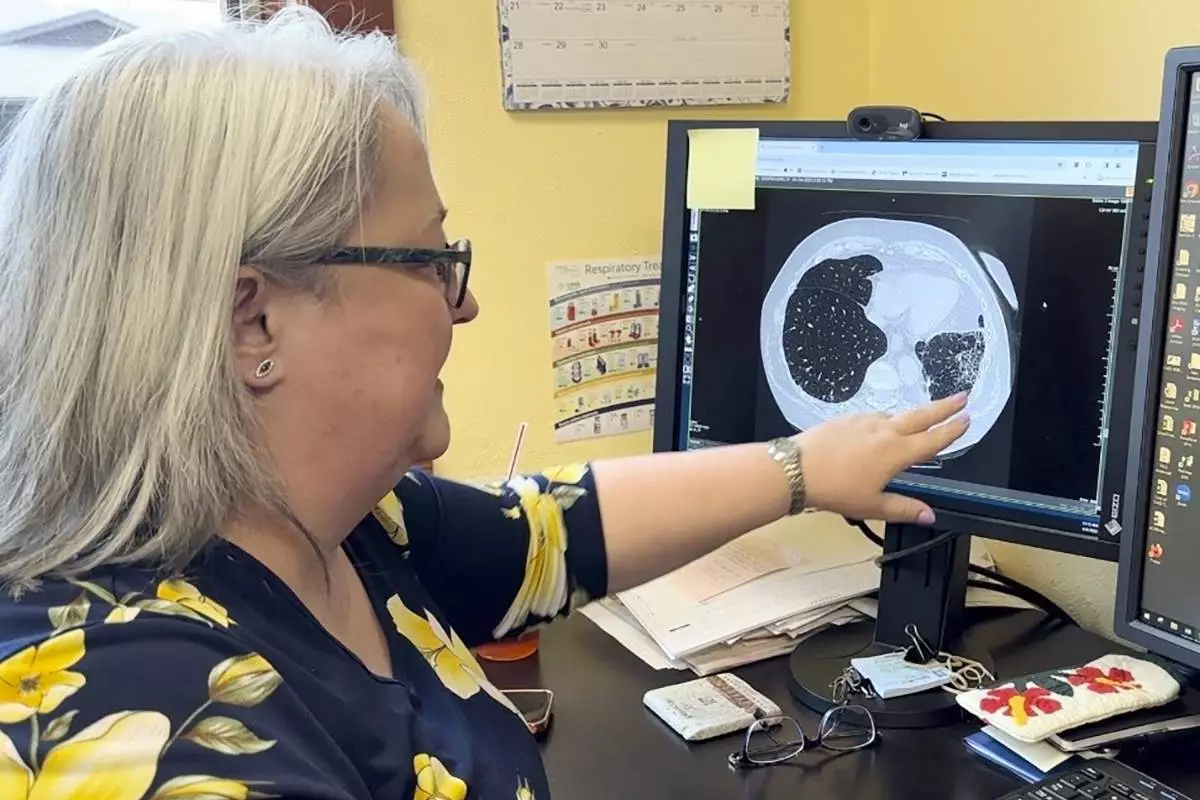

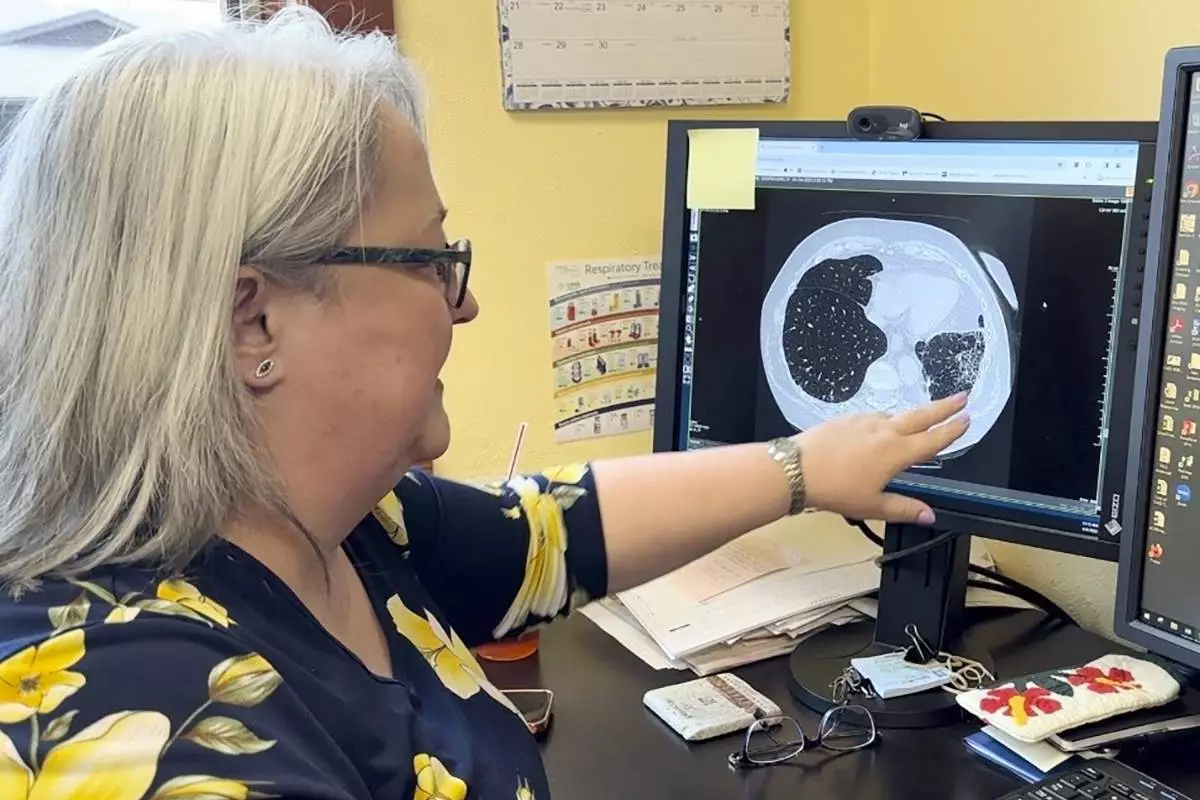

FILE - Dr. Lee Morissette shows an image of lungs damaged by asbestos exposure, at the Center for Asbestos Related Disease, Thursday, April 4, 2024, in Libby, Mont. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown, File)

FILE - In this April 27, 2011, file photo, the entrance to downtown Libby, Mont., is seen. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown, File)