As the U.N. war crimes court prepares to wrap up its work with a verdict in the landmark genocide trial of former Bosnian Serb military chief Ratko Mladic, deep divisions persist in the Balkans over the tribunal's role in delivering justice and paving the way for reconciliation in the war-torn region of Europe.

FILE - A Sept. 18, 1996 file photo shows International War Crimes Tribunal investigators clearing away soil and debris from dozens of Srebrenica victims buried in a mass grave near the village of Pilica, some 55 kms (32 miles) north east of Tuzla, Bosnia-Herzegovina. (AP Photo/Staton R. Winter, File)

Mladic's trial is the last major case for the Netherlands-based tribunal for former Yugoslavia, which was set up in 1993 to prosecute those most responsible for the worst carnage in Europe since World War II. The tribunal declared its aim is to "deter future crimes and render justice to thousands of victims and their families, thus contributing to a lasting peace in the former Yugoslavia."

Click to Gallery

As the U.N. war crimes court prepares to wrap up its work with a verdict in the landmark genocide trial of former Bosnian Serb military chief Ratko Mladic, deep divisions persist in the Balkans over the tribunal's role in delivering justice and paving the way for reconciliation in the war-torn region of Europe.

Mladic's trial is the last major case for the Netherlands-based tribunal for former Yugoslavia, which was set up in 1993 to prosecute those most responsible for the worst carnage in Europe since World War II. The tribunal declared its aim is to "deter future crimes and render justice to thousands of victims and their families, thus contributing to a lasting peace in the former Yugoslavia."

Known as the "Butcher of Bosnia," Mladic was charged with 11 counts of genocide and war crimes for the war's worst atrocities, including the 1995 slaughter by his troops of some 8,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica, or the three-year siege of the Bosnian capital Sarajevo.

The 75-year-old former general, who insists he is innocent, faces a maximum life sentence if convicted.

This ethnic divide is also reflected in how various ethnic groups judge the tribunal's legacy — Serbs, who account for the bulk of the tribunal indictments, view the court as highly biased, while the other ethnic groups in the former Yugoslavia generally harbor a more positive stance.

Chief U.N. War Crimes Prosecutor Serge Brammertz said in an interview with The Associated Press in The Netherlands that "every time a judgment is coming out in The Hague, one group will be very pleased and the other one very unhappy."

"You need a very active civil society looking for the truth and you need politicians who are willing to accept the wrongdoings of the past in order to have a joint future," he said. "This is unfortunately not really happening in the region."

"The tribunal has done tremendously important work on our behalf to dent the notion of impunity for mass atrocities in our social and political discourse," said transitional justice expert Refik Hodzic from Bosnia. "We were lucky to see this institution come to life when it did."

But, Vukcevic, said: "We are still at the level where each nation is sticking to its own truth. As long as this is so, there is no reconciliation."

More than 20 years on, however, the nations in the region are still led by nationalist politicians and remain divided deeply along ethnic lines.

FILE - A July 10, 2011 file photo shows a Bosnian man walking past shovels prepared near graves at the Potocari memorial cemetery near Srebrenica, Bosnia. (AP Photo/Amel Emric, File)

Known as the "Butcher of Bosnia," Mladic was charged with 11 counts of genocide and war crimes for the war's worst atrocities, including the 1995 slaughter by his troops of some 8,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica, or the three-year siege of the Bosnian capital Sarajevo.

While widely seen as a symbol of Bosnian war horrors, Mladic is still revered as a hero by many Serbs. In his native Bosnian village of Bozinovici, the main street is named after Mladic and almost every house cherishes at least one photo of him. T-shirts with his wartime portrait and inscription "Serbian Hero" are sold on the streets of Serbian towns.

FILE - A May 29, 2011 file photo shows Bosnian Serb protesters holding posters depicting former Bosnian Serb army chief Ratko Mladic, during a protest in Mladic's hometown of Kalinovik, Bosnia-Herzegovina. Ratko Mladic will learn his fate on Nov. 22, 2017, when U.N. judges deliver verdicts in his genocide and war crimes trial. (AP Photo/Amel Emric, File)

The 75-year-old former general, who insists he is innocent, faces a maximum life sentence if convicted.

Unlike Serbs, most Muslim Bosniaks in Bosnia believe Mladic deserves to spend the rest of his days in prison. Among them is Ramiza Burzic, who lost her two sons in the Srebrenica massacre and so far has found just partial remains of one of them.

"I expect that he will be sentenced to life in prison, so that all his progeny will know what kind of a man he was and what he did," said Burzic.

FILE - A July 11, 2011 file photo shows people carrying coffins prior to a mass burial at the Potocari memorial cemetery near Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. (AP Photo/Marko Drobnjakovic, File)

This ethnic divide is also reflected in how various ethnic groups judge the tribunal's legacy — Serbs, who account for the bulk of the tribunal indictments, view the court as highly biased, while the other ethnic groups in the former Yugoslavia generally harbor a more positive stance.

"I don't think the tribunal has helped reconciliation, but rather has contributed to further worsening of the situation," Serbia's Prime Minister Ana Brnabic said recently. "No one can say that the Hague tribunal has been objective toward all sides in the conflict of the 1990s."

FILE - In this Sunday, Feb. 4, 1996 file photo, skeletal remains of victims of the 1995 massacre at Srebrenica lie on a hilltop just west of Srebrenica, Bosnia-Herzegovina. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko, File)

Chief U.N. War Crimes Prosecutor Serge Brammertz said in an interview with The Associated Press in The Netherlands that "every time a judgment is coming out in The Hague, one group will be very pleased and the other one very unhappy."

"Those reactions show much more that the underlying reasons of the conflict are still very much there," Brammertz said. "So I don't think that accountability — that a judicial process in itself — can lead to reconciliation. Reconciliation has to come from within society, has to come from the victims and perpetrators' community."

FILE - A July, 10, 2007 file photo shows a Bosnian worker passing by a human skull during exhumation at a mass grave site in a village of Budak, near Srebrenica, Bosnia-Herzegovina. (AP Photo/Amel Emric, File)

"You need a very active civil society looking for the truth and you need politicians who are willing to accept the wrongdoings of the past in order to have a joint future," he said. "This is unfortunately not really happening in the region."

The long-awaited Mladic verdict is seen as a milestone in the efforts to bring the main actors to justice. The tribunal failed to reach a final ruling in the case of Slobodan Milosevic, the former Serbian president widely regarded as the driving force behind the violent breakup of Yugoslavia, who died in his prison cell in 2006 before the end of his trial.

However, the court has so far indicted 161 people of different Balkan nationalities and sent dozens of war criminals to jail — ranging from top leaders to low-ranking soldiers. It has established evidence of large-scale atrocities against civilians such as murder, enslavement, expulsion, torture or rape.

FILE - In this July 14, 1995 file photo, refugee Ferida Osmanovic from Srebrenica is found hanged in a forest outside the U.N. base at Tuzla airport in Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina. (AP Photo/Darko Bandic, File)

"The tribunal has done tremendously important work on our behalf to dent the notion of impunity for mass atrocities in our social and political discourse," said transitional justice expert Refik Hodzic from Bosnia. "We were lucky to see this institution come to life when it did."

Experts also argue that the tribunal is primarily a legal institution that was never expected to reconcile the feuding Balkan nations, but to establish the facts based on evidence which could help future reconciliation.

Vladimir Vukcevic, Serbia's former chief war crimes prosecutor who helped arrest Mladic in 2011 after he went into hiding more than 10 years earlier, says that "the tribunal's greatest achievement was that it brought a lot of people in top positions to justice."

FILE - In this April 9, 1994 file photo, former Bosnian Serb commander Ratko Mladic, right, leaves the UN headquarters at Sarajevo airport after talks with the UN General, Sir Michael Rose and Bosnian Commander Rasim Delic. Ratko Mladic will learn his fate on Nov. 22, 2017, when U.N. judges deliver verdicts in his genocide and war crimes trial. (AP Photo/Enric Marti, File)

But, Vukcevic, said: "We are still at the level where each nation is sticking to its own truth. As long as this is so, there is no reconciliation."

The conflict in the former Yugoslavia erupted after the breakup of the former multi-ethnic federation in the early 1990s, with the worst crimes taking place in Bosnia. More than 100,000 people died and millions lost their homes before a peace agreement was signed in 1995.

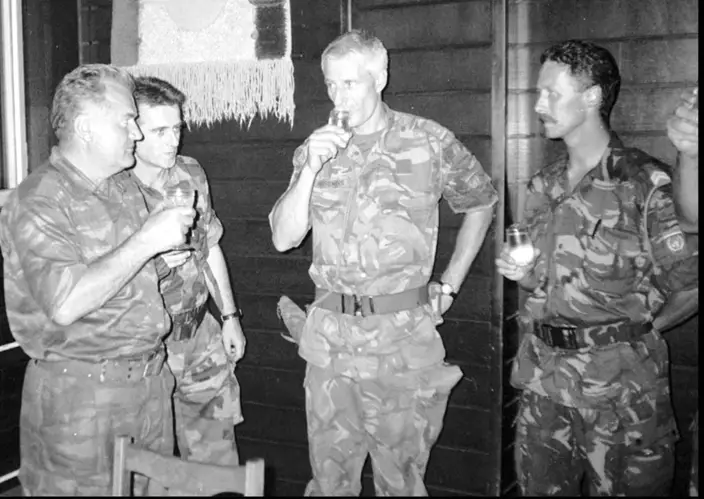

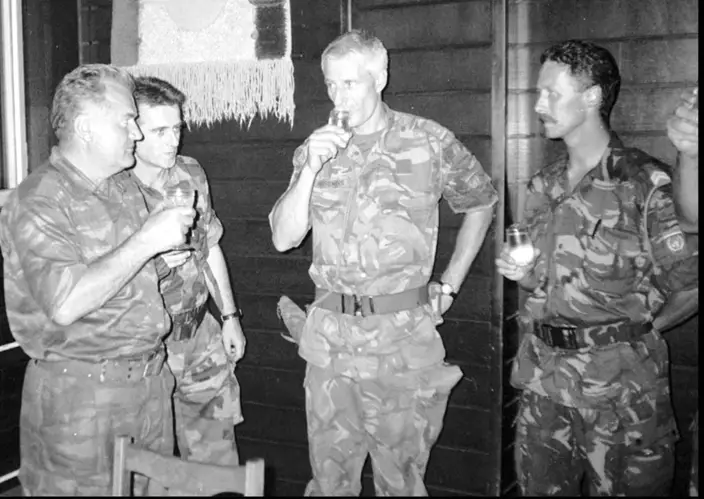

FILE - In this July 12, 1995 photo, Bosnian Serb army Commander General Ratko Mladic, left, drinks toast with Dutch U.N Commander Tom Karremans, second right, while others unidentified look on in village of Potocari, some 5 kilometers (3 miles) north of Srebrenica. Ratko Mladic will learn his fate on Nov. 22, 2017, when U.N. judges deliver verdicts in his genocide and war crimes trial. (AP Photo)

Prominent Serbian human rights expert Natasa Kandic agrees that "people had unrealistic expectations" the tribunal would do the job of building trust among the countries and societies of the region.

"Decades will need to pass for trust to be established between the different (Balkan) nations," Kandic said. "No court can do that."

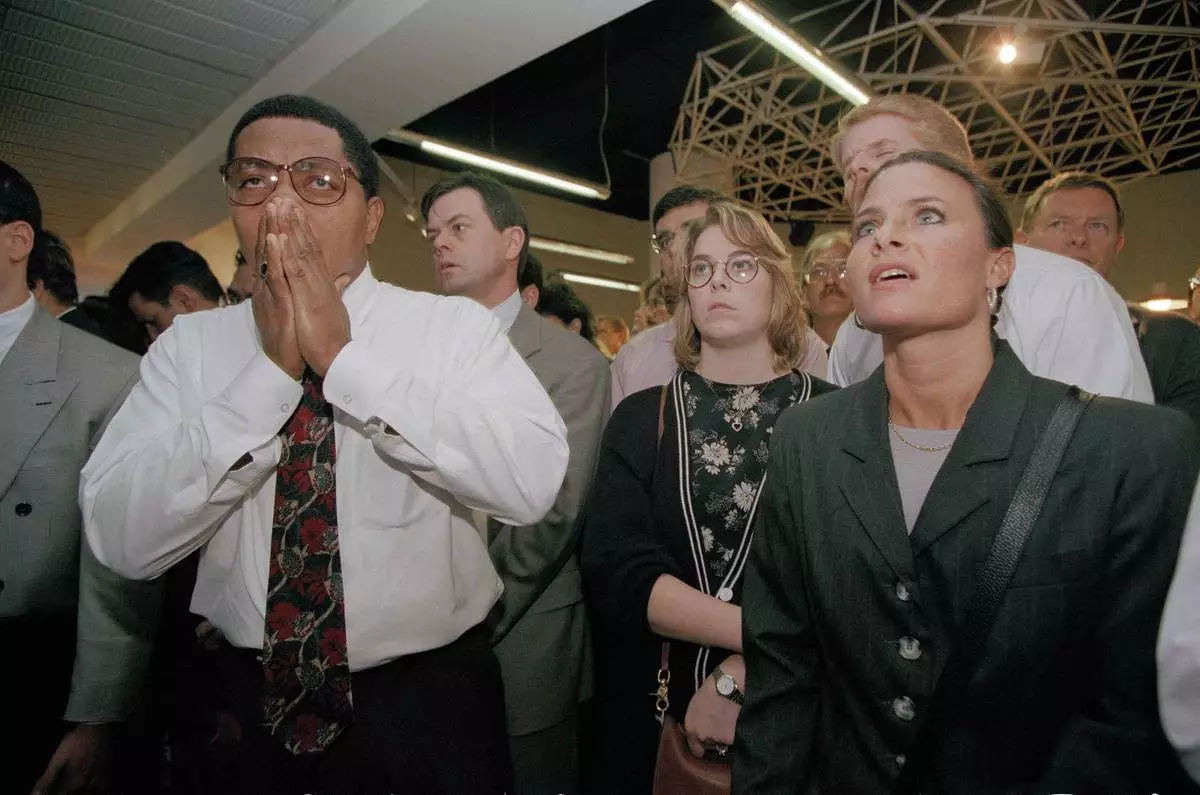

For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson’s murder trial, his 1995 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans.

Some people recall watching their Black co-workers and classmates erupting in jubilation at perceived retribution over institutional racism. Others remember their white counterparts shocked over what many felt was overwhelming evidence of guilt. Both reactions reflected different experiences with a criminal justice system that continues to disproportionately punish Black Americans.

Simpson, who died Wednesday, remains a symbol of racial divisions in American society because he is a reminder of how deeply the inequities are felt, even as newer figures have come to symbolize the struggles around racism, policing and justice.

“It wasn’t really about O.J. Simpson the man. It was about the rest of the society and how we responded to him,” said Justin Hansford, a Howard University law professor.

Simpson died of prostate cancer in Las Vegas, his family announced Thursday. He was 76.

His death comes just a few months before the 30th anniversary of the 1994 killings of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman. Much like the trial, the public’s reaction to the verdict was largely shaped by race.

Today, criminal justice reforms that address racial inequities are less divisive. But that has been replaced by backlash against diversity, equity and inclusion programs, bans of books that address systemic racism, and restrictions around Black history lessons in public schools.

“The hard part is we’re going to keep cycling through this until we learn from our past,” said University of Pennsylvania sociologist and Africana Studies professor Camille Charles. “But there are people who don’t want us to learn from our past.”

During the trial, African Americans were four times as likely to presume Simpson was innocent or being set up by the police, said UCLA Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Darnell Hunt, who at the time was a young sociologist writing a book about the different ways Black and white Americans saw the trial.

“The case was about two different views of reality or two different takes on the reality of race in America at that point in history,” he said.

Simpson’s trial came on the heels of the 1992 acquittal of police officers in the beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles, which was caught on video and exposed America’s deep trauma over police brutality. For many African Americans in 1995, Simpson’s acquittal represented a rebuke of institutional racism in the justice system. But many white Americans believed Simpson and his defense team played the race card to get away with the killings.

The difference could also be seen in the ways Black media outlets covered the trial compared to mainstream publications, Hunt said. Those outlets tended to raise questions about whether the justice system was really fair in terms of "what might be called the Black experience,” he said.

Polling in the last decade shows most people still believe Simpson committed the killings, including most African Americans, but the racial and historical dynamics at play in the trial made it about more than the deaths.

Hansford, the Howard University law professor who is Black and was 12 years old at the time of the Simpson verdict, said he remembers the differences in white and Black reactions even in liberal environments like Silver Spring, Maryland, the Washington suburb where he grew up.

“When he was acquitted, all the Black students celebrated and ran into the hallways, jumping up and down,” he said. “And the white teachers were crying.”

One of Hansford’s white teachers said something about Simpson that he didn’t agree with, and when he responded, the teacher rebuked him.

“It was one of the worst ways a teacher has ever talked to me,” Hansford said. “The O.J. Simpson trial created a situation where people were dug into their sides.”

The racial turmoil embedded in the court case was at the center of the 2016 Oscar-winning documentary “OJ: Made in America.” Instead of focusing on the killings and the evidence presented at trial, director Ezra Edelman placed the crimes within the context of the Civil Rights struggle, from which Simpson was largely insulated by the warm embrace of the white mainstream.

“All O.J. had to do to get recognized is to run a football," Edelman told the AP in 2016. "And almost concurrent to that you have a community of people whose only way to get recognized is to burn their community down during the (1965 Watts) riots. Those were the two tracks I was trying to home in on, knowing that they will intersect 30 years later.”

Simpson had married a white woman in a nation that had historically punished Black men who dared to explore mixed-race relationships. But Simpson also was a former football star, a wealthy Hollywood actor and brand spokesman whose money and privilege distinguished him from impoverished Black men that the criminal justice system punished.

“I’m not Black, I’m O.J.,” he liked to tell friends.

He had been admired as a one-of-a-kind celebrity whose transgressions, including a pattern of spousal abuse, were overlooked as incompatible with his All-American persona.

“He actually seemed to go to quite a bit of trouble to distance himself from Black folks," but the Black support for him wasn't about that, said Charles, the University of Pennsylvania sociologist. “I think it was about seeing the system work the way we were told it was supposed to.”

Even as systemic racism in criminal justice systems remains an issue, Charles thinks Black Americans have grown less likely to believe in a famous defendant’s innocence as a show of race solidarity.

“The one thing that has changed is that you didn’t see the same kind of getting behind (R&B singer) R. Kelly or Bill Cosby,” Charles said.

“There was much more open conflict about them, and many more Black people were willing to say publicly, ‘Nah, he did that.’ I think it also could represent a better understanding of celebrity and wealth,” she said.

Graham Lee Brewer reported from Oklahoma City, and Aaron Morrison from New York. They are members of AP's Race and Ethnicity team.

FILE - Members of O.J. Simpson's family react as the not guilty verdict is read in a Los Angeles courtroom Tuesday, Oct. 3,1995. From left are mother Eunice (in hat), daughter Arnelle, unidentified woman, son Jason and sister Shirley Baker. For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson's murder trial, his 1994 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans. (AP Photo/Pool, Myung J. Chun, File)

FILE - Supporters of O.J. Simpson react outside the Criminal Courts Building to the verdict of not guilty in Simpson's double-murder trial in Los Angeles, Oct. 3, 1995. For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson's murder trial, his 1994 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans. (AP Photo/Elise Amendola, File)

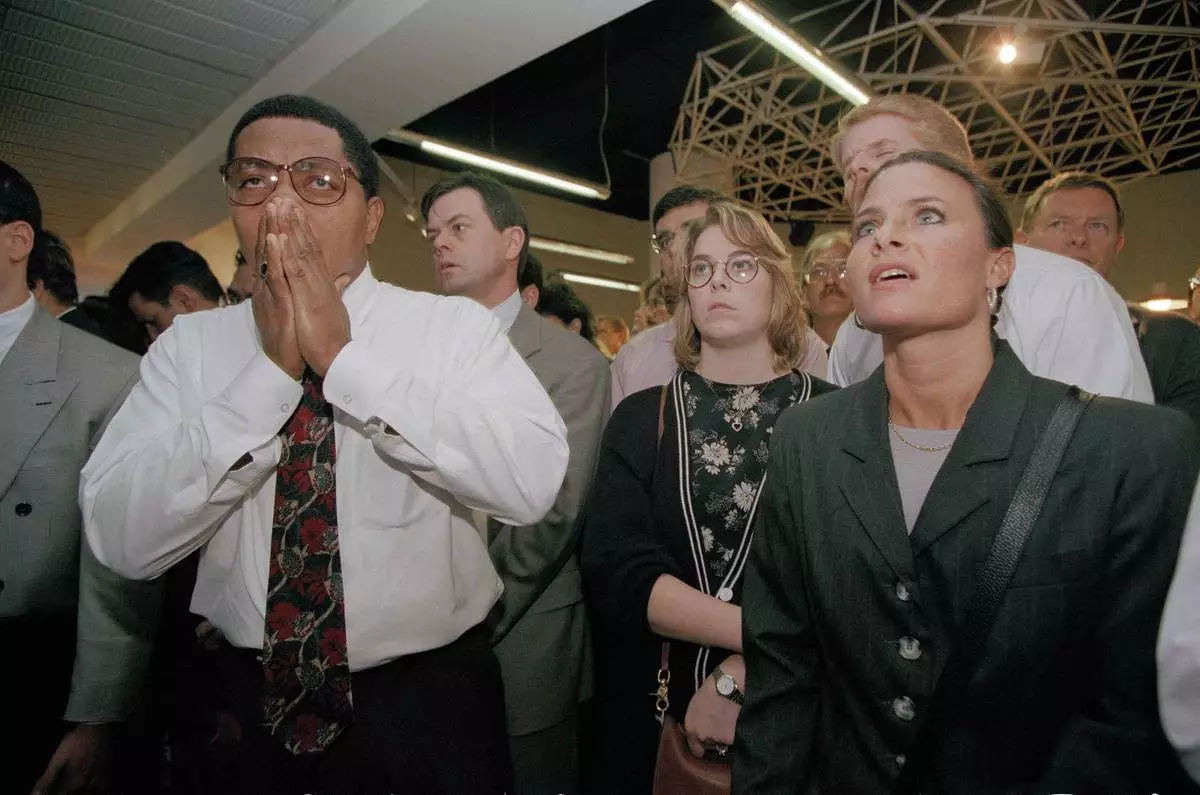

FILE - Christopher Odle, 36, a legal clerk from Crown Heights, Brooklyn, borough of New York, left, wipes away tears moments after hearing the news that O.J. Simpson was found not guilty of killing Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman, in New York, Oct. 3, 1995. At right is Bernadette B. Incerto, 33. For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson's murder trial, his 1994 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans. (AP Photo/Clark Jones)

FILE - In this Oct. 3, 1995 file photo, Justin Barker, left, and his colleague Juan Borrego react as they hear the verdict of the O.J. Simpson trial in Miami. For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson's murder trial, his 1994 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

FILE - A crowd of pedestrians react as they watch the Jumbotron television screen in New York's Times Square, Oct. 3, 1995, and the news that O.J. Simpson was found not guilty of killing Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman. For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson's murder trial, his 1994 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans. (AP Photo/Rosario Esposito, File)

FILE - Bill Cosby arrives for his sentencing hearing at the Montgomery County Courthouse, Sept. 24, 2018, in Norristown, Pa. For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson's murder trial, his 1994 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans. Simpson, who died Wednesday, April 10, 2024, remains a symbol of racial divisions in American society because he is a reminder of how deeply inequities are felt, even as newer figures have come to symbolize the struggles around racism, policing and justice. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum, File)

FILE - R. Kelly arrives at the Cook County Criminal Court Building, in Chicago, June 13, 2008. For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson's murder trial, his 1994 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans. Simpson, who died Wednesday, April 10, 2024, remains a symbol of racial divisions in American society because he is a reminder of how deeply inequities are felt, even as newer figures have come to symbolize the struggles around racism, policing and justice. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh, File)

FILE - In this May 1, 1992 file photo, Rodney King makes a statement at a Los Angeles news conference, where he asked for an end to violence. For many people old enough to remember O.J. Simpson's murder trial, his 1994 exoneration was a defining moment in their understanding of race, policing and justice. Nearly three decades later, it still reflects the different realities of white and Black Americans. Simpson, who died Wednesday, April 10, 2024, remains a symbol of racial divisions in American society because he is a reminder of how deeply inequities are felt, even as newer figures have come to symbolize the struggles around racism, policing and justice. (AP Photo/David Longstreath, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 3, 1995 file photo, attorney Johnnie Cochran Jr. holds O.J. Simpson as the not guilty verdict is read in a Los Angeles courtroom during his trial in Los Angeles. Defense attorneys F. Lee Bailey, left, Robert Kardashian look on. Simpson, the decorated football superstar and Hollywood actor who was acquitted of charges he killed his former wife and her friend but later found liable in a separate civil trial, has died. He was 76. (Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Daily News via AP, Pool, File)