More than two decades after poison gas attacks in Tokyo's subways killed 13, the stage has shifted to the execution of 13 people convicted in the crime. When they will be sent to the gallows, though, remains a mystery in Japan's highly secretive death penalty system.

The Supreme Court rejected an appeal in the final case last week, so the condemned are no longer needed as potential trial witnesses. The court upheld a life sentence for Katsuya Takahashi, a driver in the attack who was convicted of murder in 2015. He was a follower of the Aum Shinrikyo cult that carried out the attack.

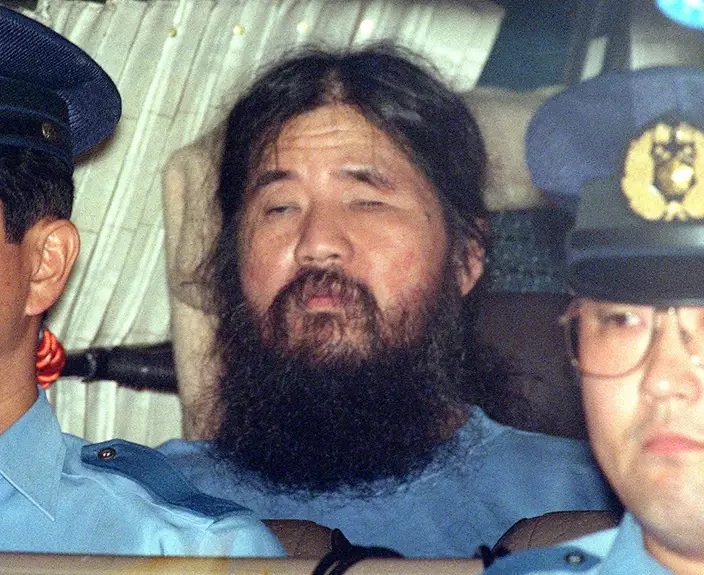

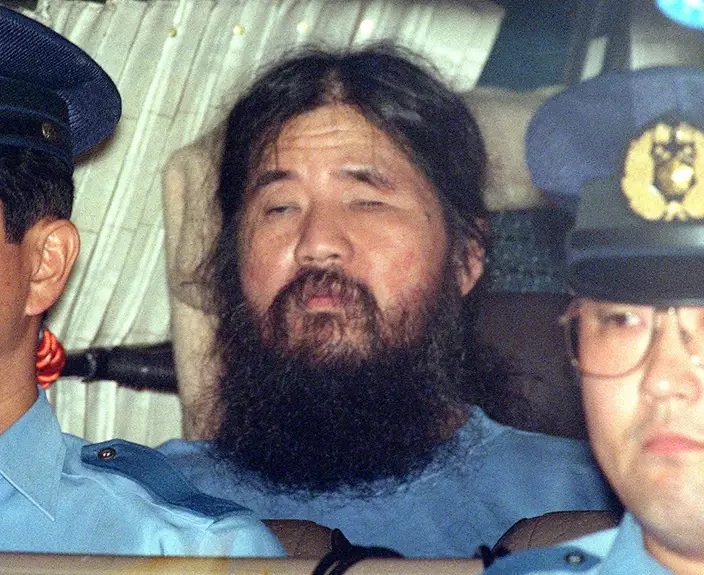

FILE - In this Sept. 25, 1995, file photo, cult leader Shoko Asahara, center, sits in a police van following an interrogation in Tokyo. More than two decades after poison gas attacks in Tokyo’s subways killed 13 people, the stage has shifted to the execution of the 13 major perpetrators. (Kyodo News via AP, File)

"The end of the trials, which took so long, is a fresh reminder of the horror of all the crimes committed by Aum," Shizue Takahashi, the wife of a subway stationmaster who died in the attack, told reporters Friday. "Now the focus for the families of the victims and other people will shift to the executions."

Shoko Asahara, the guru of Aum Shinrikyo, and 12 others have been sentenced to death. Whether any will be hanged this year is unknown. Japan generally announces executions only after they have happened.

Cult members released sarin nerve gas in subway cars during the morning rush hour in March 1995, sending people fleeing to the streets and sickening more than 6,000. First-aid stations were set up in tents, and military troops in gas masks and hazmat suits were sent in. The scenes shocked a country where the crime rate is relatively low and people usually take their personal safety for granted.

FILE - In this June 15, 2012, file photo, Katsuya Takahashi, center, a former Aum Shinrikyo cult member, is driven to Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department after being arrested, in Tokyo. (Kyodo News via AP, File)

"We should remember that it was not a crime by a group of weird young people, but it showed that anyone could be an assailant," said Shoko Egawa, a journalist who covered the cult's criminal activities from early on.

The attack was intended to disrupt a police investigation into the group, which had already been suspected of other illegal activities. The cult had amassed an arsenal of chemical, biological and conventional weapons in anticipation of an apocalyptic showdown with the government.

Cult guru Asahara, whose real name is Chizuo Matsumoto, was captured two months after the attack. His round face framed by wavy long hair and a scraggly beard, he rarely spoke during an eight-year trial, except for occasional incoherent remarks in English at the start. Now 62 years old, he has been on death row for nearly 14 years since being sentenced in 2004.

Aum Shinrikyo, which means Supreme Truth, once claimed 10,000 members in Japan and 30,000 in Russia. It has disbanded, though about 2,000 believers follow its rituals in two splinter groups. Authorities continue to monitor them.

FILE - In this undated file photo, cult guru Shoko Asahara, left, of Aum Shinrikyo walks with Yoshihiro Inoue, then a close aid, in Tokyo. (Kyodo News via AP, File)

Of the 122 people on death row in Japan, more than 90 are appealing their sentences. Retrials are rarely granted, and filing an appeal does not protect one from the gallows. Four people were executed last year.

In 2016, the Japan Federation of Bar Associations called on the government to abolish executions by 2020, when Japan hosts the Summer Olympics. Japan and the U.S. are the only G-7 countries that maintain the death penalty. Last year, Mongolia became the 105th nation to end the practice, according to Amnesty International.

TOKYO (AP) — Spicy, steaming, slurpy ramen might be everyone’s favorite Japanese food.

In Tokyo, long lines circle around blocks, and waiting an hour for your ramen is normal. What awaits might be just a dive, but a hot bowl of ramen rarely fails to hit the spot.

Often cooked right before your eyes behind dingy counters, the noodle dish starts here at around 1,000 yen ($6.50), and comes in various flavors and local versions. There's salty, soy-based “shoyu” or “miso” paste. Perhaps it's red-hot spicy with a dash of chili. Sometimes there's no soup at all but a sauce to dip the noodles in.

The curly noodles are lighter than the darker buckwheat “soba,” or “udon,” which are also usually flatter or thicker.

Ramen has also surged in popularity in the U.S., South Korea and other countries. Retail sales in the United States have risen 72% since 2000, according to NielsenIQ, a sales tracker. In the 52 weeks ending April 13, Americans bought more than $1.6 billion worth of ramen.

In restaurants, versions beyond the traditional soup are appearing, said Technomic, a research and consulting company for the restaurant industry. Del Taco, a Mexican chain, recently introduced Shredded Beef Birria Ramen, for example.

Packaged ramen that's easily cooked in hot water at home is called instant noodles; it's precooked and then dried. The story of how Momofuku Ando invented instant ramen in a backyard shed in 1958, when food was still scarce, is the stuff of legend in Japan. He went on to found the food giant Nissin Foods.

Although convenient, instant noodles aren't the same as the ramen served at restaurants.

Some Japanese frequent ramen shops twice or three times a week. They emerge, dripping with sweat, smacking their lips.

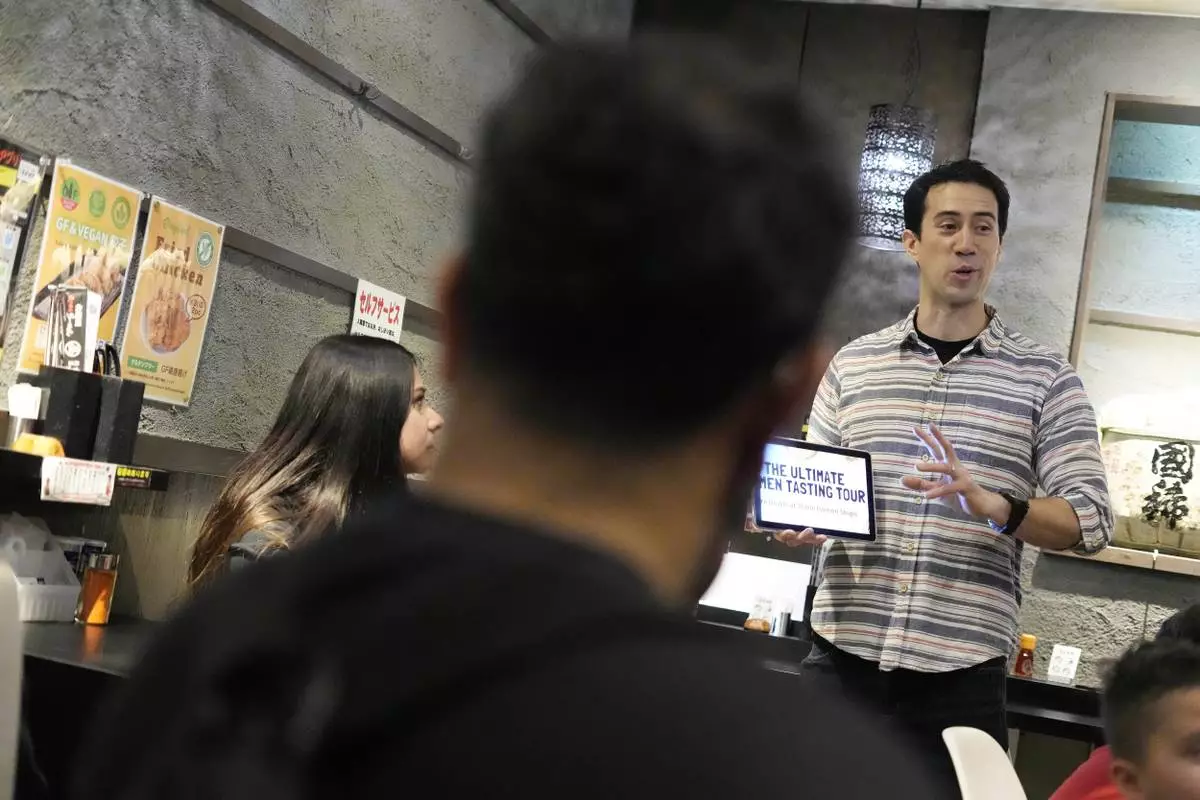

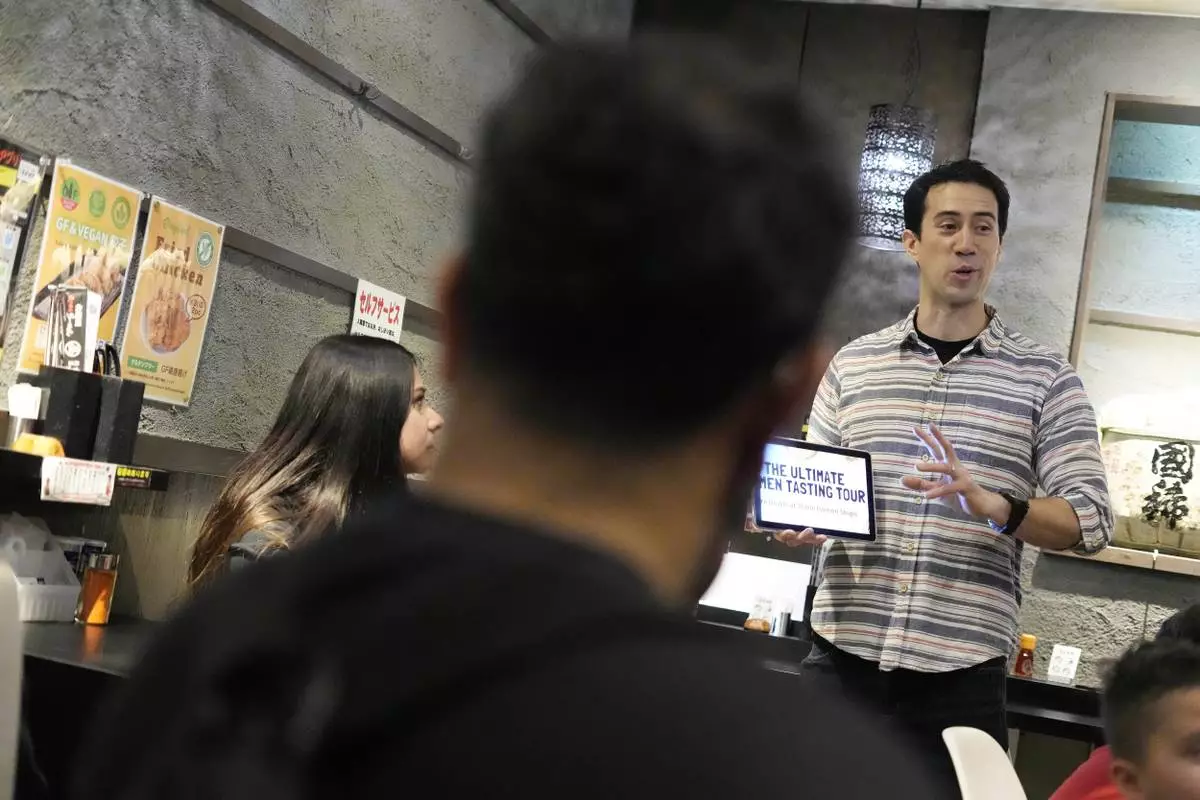

“I’m probably a talking bowl of ramen,” says Frank Striegl as he leads a dozen American tourists through the back alleys of Tokyo’s funky Shibuya district on what he calls “the ultimate ramen experience.”

The crowd is led behind a shabby doorway, sometimes down narrow stairs, to a dim-lit table where ramen gets served in tiny bowls, practically the size of a latte cup, or about a quarter of a regular ramen bowl. That's so guests have enough room in their tummies to try out six different kinds of ramen, two at each spot during the tour.

One restaurant, Shinbusakiya, offers “Hokkaido classics” from the northernmost main island, while another, Nagi, offers “Fukuoka fusion,” from the southern main island of Kyushu. It includes a green ramen, similar to pasta al pesto. Syuuichi, which means “once a week,” features curry-flavored ramen.

“It’s not just, of course, about eating delicious ramen, but also learning about it,” said Striegl, a Filipino American who grew up in Tokyo. He calls ramen “people’s food.”

“A lot of countries around the world have their version of ramen in a way," he said. "So I think because of that, it’s a dish that’s easy to understand. It’s a dish that’s easy to get behind.”

While the tour participants were relishing their noodles, Striegl outlined a brief history of ramen: Its roots date back to the samurai era, when a shogun took a fancy to Chinese noodles, setting off the localizing journey for ramen that continues today.

Katie Sell, a graduate student on Striegl’s tour, called ramen "a kind of comfort food, especially in the winter. Get a group of friends, go have some ramen and just enjoy it.”

Kavi Patel, an engineer from New Jersey, said he was glad he included the humble ramen on his tour of Japan, along with more established attractions like the ancient capital of Kyoto and the deer park in Nara. “I’m having good fun,” he said.

While ramen has never been more popular in Japan, ramen places have struggled because of the pandemic, the weakening Japanese yen, and the higher cost of wheat imports and energy, according to a study by Tokyo Shoko Research.

One beneficiary of the pandemic is a home delivery service for frozen, professionally cooked ramen. Called takumen.com, it boasts some 500,000 subscribers in Japan.

Another Tokyo operation, Gourmet Innovation, has signed on 250 of the country's top ramen joints to sell packaged versions of their soup, noodles and toppings, to be heated up in boiling water and served at home.

Co-founder and executive Kenichi Nomaguchi, who hopes to expand his business overseas, says ramen and animation are Japan’s most successful exports.

Why ramen? Unlike pasta or curry, ramen is difficult to replicate at home, he said, Making it from scratch involves hours of cooking stock, with pork, beef or chicken, various fish or bonito flakes, and “kombu” kelp. Some stock uses oysters.

Besides the different soup stocks and flavors, onions, grated garlic, ginger or sesame oil can be added for extra punch. Toppings can include bean sprouts, barbecued pork, boiled or raw eggs, seaweed, fermented bamboo shoots called “menma,” chopped green onions, cooked cabbage, snow peas or corn.

Some insist a bowl of ramen is not complete without a slice of narutomaki, a whitefish cake with a pink spiral pattern.

Unusual varieties include coffee ramen and ramen topped with ice cream or pineapple.

Jiro-style ramen, named for a legendary restaurant in Tokyo, features mounds of vegetable toppings, huge steak-like barbecued pork and pungent, grated garlic seeped in a fatty pork-based stock.

“Impact is important. So the pork has to be big so it’s truly memorable,” said Kota Kobayashi, who serves Jiro-style ramen at his chain, “Ore No Ikiru Michi,” which translates to, “The way I live my life.”

Kobayashi is a former professional baseball player at the Yokohama Bay Stars, and played with the minor league Cleveland Guardians before switching to his ramen business.

“When I quit baseball, I chose ramen as my way of life,” he said with a smile.

He can wax philosophical about ramen. One cultural difference he has observed is that Americans tend to leave the noodles and drink all the soup, while the Japanese mostly do the opposite.

And taste is only part of what makes good ramen. One must also offer entertainment, Kobayashi said.

At his restaurants, the chopsticks are tucked in a box on a shelf, so first-time visitors ask where they are. Repeat customers go straight to that box. Kobayashi calls out, “Welcome back,” making the customers feel a connection, even if he doesn't remember a thing about them.

Dee-Ann Durbin contributed to this story from Detroit.

Yuri Kageyama is on X: https://twitter.com/yurikageyama

Kota Kobayashi, owner of a chain ramen shop called "Ore No Ikiru Michi," speaks during an interview with The Associated Press on April 17, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Kota Kobayashi prepares a bowl of noodle at his chain called "Ore No Ikiru Michi" in Tokyo on April 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Co-founder and executive Kenichi Nomaguchi of Gourmet Innovation, speaks during an interview with The Associated Press in Tokyo, on April 10, 2024. Gourmet Innovation has signed on 250 of the country's top ramen joints to sell packaged versions of their soup, noodles and toppings, to be heated up in boiling water and served at home. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Co-founder and executive Kenichi Nomaguchi of Tokyo-based Gourmet Innovation, explains on the merchandise during an interview with The Associated Press, in Tokyo on April 10, 2024. Gourmet Innovation has signed on 250 of the country's top ramen joints to sell packaged versions of their soup, noodles and toppings, to be heated up in boiling water and served at home. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A staff member cooks one of their ramen merchandise sold online at Gourmet Innovation in Tokyo, on April 10, 2024. Gourmet Innovation has signed on 250 of the country's top ramen joints to sell packaged versions of their soup, noodles and toppings, to be heated up in boiling water and served at home. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A staff member cooks one of their ramen merchandise sold online at Gourmet Innovation, in Tokyo Wednesday, April 10, 2024. Gourmet Innovation has signed on 250 of the country's top ramen joints to sell packaged versions of their soup, noodles and toppings, to be heated up in boiling water and served at home. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Frank Striegl, right, a guide of Tokyo Ramen Tours, explains foreign participants of a ramen tasting tour at Shinbusakiya, a ramen shop which offers "Hokkaido classics," at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Frank Striegl, a guide of Tokyo Ramen Tours, walks inside Nagi, which offers "Fukuoka fusion," type ramen at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A chef cooks noodle for participants of Tokyo Ramen Tours at Nagi, which offers "Fukuoka fusion," type ramen at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A staff member prepares to serve noodles for participants of Tokyo Ramen Tours at Syuuichi, which means "once a week," featuring curry-flavored ramen, at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Frank Striegl, bottom right, a guide of Tokyo Ramen Tours, explains participants of a ramen tasting tour at Nagi, which offers "Fukuoka fusion," type ramen at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Chefs prepare noodles for participants of Tokyo Ramen Tours at Syuuichi, which means "once a week," featuring curry-flavored ramen, at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Participants of Tokyo Ramen Tours enter Shinbusakiya, a ramen shop which offers "Hokkaido classics," at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Frank Striegl, center, a guide of Tokyo Ramen Tours, leads several participants of a ramen tasting tour near Shibuya pedestrian crossing at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Frank Striegl, standing at center, a guide of Tokyo Ramen Tours, explains foreign participants of a ramen tasting tour at Nagi which offers "Fukuoka fusion," type ramen at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Participants eat the noodle at Shinbusakiya, a ramen shop which offers "Hokkaido classics," during Tokyo Ramen Tours at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A staff member prepares small bowls of noodle for participants of Tokyo Ramen Tours at Shinbusakiya, a ramen shop which offers "Hokkaido classics," at Shibuya district on April 2, 2024, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)