For Russian mother Farkhanur Gavrilova, the blow came a week ago when an acquaintance called her to say that her son was killed in a U.S. airstrike in Syria that pitted Russian and U.S. combatants against each other for the first time in the Syrian war.

Farkhanur Gavrilova, mother of Ruslan Gavrilov who is reported to have killed in Syria, looks on while speaking to the Associated Press in the village of Kedrovoye, Russia, Thursday, Feb. 15, 2018. (AP Photo/Nataliya Vasilyeva)

Gavrilova's son, 37-year-old Ruslan Gavrilov, was one of seven men in this central Russian village of 2,300 who are believed to have joined a private military company called Wagner. The company reportedly was involved in a Feb. 7 attack on U.S.-backed Kurdish fighters in Syria and suffered devastating losses in a U.S. counterstrike.

On the morning of Feb. 8, she said, her son's colleague called to say he was told by an unidentified caller that Ruslan had died in the Feb. 7 airstrike.

(AP Photo/Nataliya Vasilyeva)

"He was torn to pieces," the 67-year-old said, speaking Thursday in her sparsely furnished apartment. "If he was alive — he is a plucky guy — he would have tried to call."

The Russian Foreign Ministry on Thursday for the first time acknowledged that five Russians had been killed by the U.S. strike in Syria, emphasizing they weren't on active military duty. Previously, both Russian and U.S. officials said they had no information on Russian casualties in the clash.

People walk past a house with a Soviet-era slogan that reads "Glory to the Party, Motherland and People!" in the village of Kedrovoye, Russia, Thursday, Feb. 15, 2018. (AP Photo/Nataliya Vasilyeva)

Russian forces are supporting the Syrian government in the fight against opposition groups, some of which are backed by the United States, and elements of both sides are fighting the last remnants of the Islamic State group in Syria. Moscow and Washington long have feared a collision between Russian and U.S. combatants in Syria and sought to prevent it by maintaining a regular communications link between the militaries.

Observers blame the Feb. 7 clash on a lack of coordination between the Russian military and private military contractors in Syria.

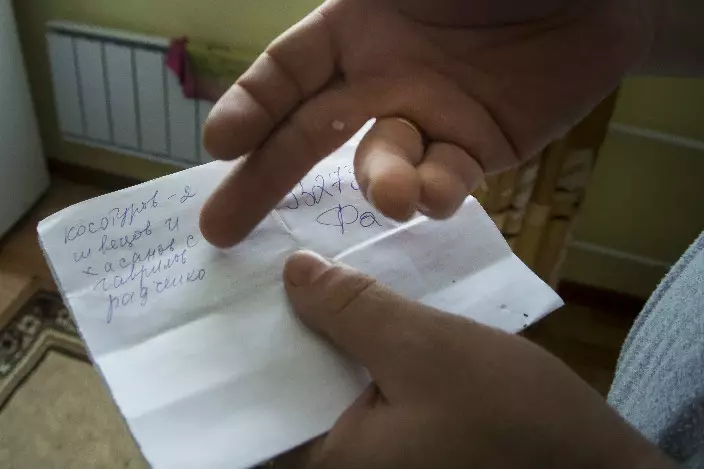

Yevgeny Berdyshev shows a list that residents of the village have compiled of the locals who are fighting in Syria, in Kedrovoye, Russia, Thursday, Feb. 15, 2018. (AP Photo/Nataliya Vasilyeva)

Along with the Russian military, thousands of Russians have also reportedly fought in Syria as private contractors. That allows the Kremlin to keep the official death toll from its Syrian military campaign low, helping to avoid negative publicity as President Vladimir Putin runs for re-election in Russia's March 18 presidential vote.

Gavrilova said she had tried to dissuade her son, who was remodeling apartments, from going to Syria but he was lured by a promise of a high pay.

Yevgeny Berdyshev, half-brother of Alexander Potapov who is believed to be fighting in Syria, stands at the window at his home in the village of Kedrovoye, Russia, Thursday, Feb. 15, 2018. (AP Photo/Nataliya Vasilyeva)

"Why did they leave? Because of poverty, to make money," Gavrilova said.

Russian law forbids the hiring of mercenaries or working as one.

Putin declared victory in Syria on a visit to a Russian military base there in December, and ordered a partial pullout of troops. Many Russian politicians and commentators long have assailed the Kremlin for failing to acknowledge the Russian contractors' presence in Syria.

A push for oil assets appears to have been the top mission for Russian private contractors in Syria. The Associated Press last year obtained a copy of a contract between a Russian company and the Syrian government that would give the Russians a 25 percent cut of the proceeds from the oil fields they capture and guard.

Unlike many other military contractors with previous experience of fighting alongside Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine, Gavrilova's son hadn't even done his military service.

"I thought they went there to do some odd jobs," Gavrilova said. "They did not even undergo medical tests. He called me from Krasnodar and asked: 'Mother, what is my blood type?'"

The Krasnodar region in southern Russia hosts a training base for the Wagner company on the grounds of a Russian Defense Ministry installation, according to social media evidence and testimony of the relatives. A listing for the company could not be found to seek comment.

Gavrilova and a relative of another Wagner fighter said the men from Kedrovoye all traveled to Krasnodar before traveling to Syria.

Asked if she knew anyone else in the village whose family members were fighting in Syria, Gavrilova pointed at a two-story house just across the yard. Yevgeny Berdyshev, interviewed there, quoted his half brother Alexander Potapov as saying he was driven to go to Syria by "patriotic sentiment."

"He would say: 'Putin is waging the right war. He's killing IS fighters . but I understand, of course, that he didn't have a choice," Berdyshev said.

Potapov, a 54-year-old father of two, had fought in two separatist wars in Chechnya. Yet work was hard to come by, especially because he was no longer young, had a hand injury and a criminal conviction, Berdyshev said. Potapov worked at a sawmill before he left in October last year with Gavrilov.

Starved of reliable information about Russians in Syria, the residents in Kedrovoye, 1,400 kilometers (880 miles) east of Moscow, are getting together, compiling lists of who went to Syria and exchanging any news they get from the men's associates.

Potapov's brother showed a piece of paper with six names of other locals now in Syria.

One more, Igor Kosoturov, originally from the nearby town of Asbest but linked to Kedrovoye people, is also believed to have been killed in Syria. Natalya Krylova, a local legislator in Asbest, confirmed Kosoturov's death.

Krylova, who has been friends with him for several decades, said the 45-year-old Kosoturov went to fight alongside Russia-backed rebels in eastern Ukraine in 2015 and received the town's award for a "humanitarian mission" there.

Oleg Surnin, head of a paramilitary Cossack group in Asbest, said by phone it was "evident" that Kosoturov and another Asbest resident, Stanislav Matveyev, were killed in the U.S. airstrike on Feb. 7, but he wouldn't elaborate.

The grieving families are waiting for those who survived the U.S. strike to come home and describe what happened to the others.

"At first, everyone was weeping out loud, but how long can you cry?" Gavrilova said. "It's the uncertainty that's gnawing at me."

She said she couldn't understand why Russian men ended up on a battlefield in Syria if they were not part of the Russian army.

"Why were they taken away? Why does this organization exist?" she asked.

Berdyshev is indignant about the Russian government's refusal to even acknowledge the existence of the private contractors.

"They do exist," he said. "The government sends in troops, it is responsible for its actions . They sent in the troops, they sent back the troops, but actually there are still some (Russians), and it's all secretive."