Sara al-Matoura watched through a window as her one-year-old daughter's chest heaved up and down under a tangle of medical wires.

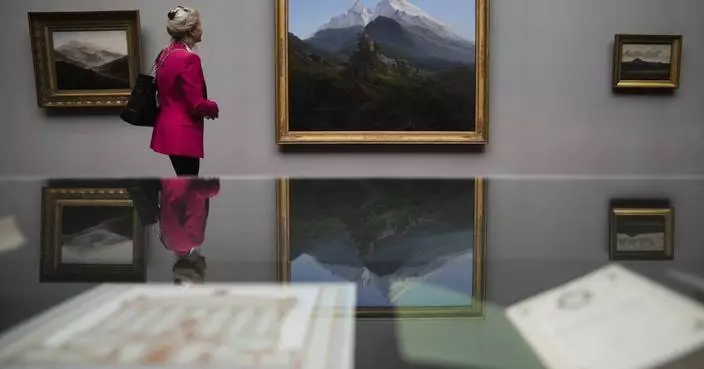

In this March 5, 2018 photo, one-year-old Syrian refugee Eman Zatima is prepared by medical staff for surgery, at a hospital in Amman, Jordan. Eman, who has a heart defect, received a life-saving pro bono surgery from doctors sent by the Vatican's Bambino Gesu Hospital. (AP Photo/Raad Adayleh)

The 22-year-old mother from the Syrian city of Homs hadn't eaten for a day and stayed up all night at a hospital in the Jordanian capital, Amman, holding her daughter, imagining the scalpel cutting her baby's chest open.

Al-Matoura, who fled the Syrian war for Jordan in 2012, was only four months pregnant with her second child when she found out the baby had a congenital heart defect known as tricuspid atresia, which has a mortality rate of 90 percent before age 10.

Jordanian doctors encouraged her to abort the fetus. Al-Matoura refused. "She is my gift from God," she said. She named her daughter Eman — "faith" in Arabic.

In this Monday, March 5, 2018 photo, Jordanian and Italian doctors brief Syrian refugee Sara al-Matoura before performing surgery on her one-year-old daughter Eman at a hospital in Amman Jordan. Eman, who has a heart defect, received a life-saving pro bono surgery from doctors sent by the Vatican's Bambino Gesu Hospital. (AP Photo/Raad Adayleh)

Last week, Eman received life-saving open heart surgery, one of eight cardiac operations that Italian pediatric surgeons from the Vatican's Bambino Gesu Hospital came to perform for free in Jordan.

Dozens of other Syrian refugees with cancer, heart defects and other complex conditions go untreated each month because of funding constraints, according to U.N. officials. The more expensive the treatment, the more likely their funding requests will be turned down. Even primary care and basic services such as child delivery are increasingly unaffordable.

Some 5.5 million Syrians have fled their homeland since 2011, most settling in the region. Jordan currently hosts more than 650,000 Syrians registered by the U.N. refugee agency, though the government estimates the number of Syrians in the country is twice as high.

In this March 5, 2018 photo, one-year-old Syrian refugee Eman Zatima is prepared by medical staff for surgery, at a hospital in Amman, Jordan. Eman, who has a heart defect, received a life-saving pro bono surgery from doctors sent by the Vatican's Bambino Gesu Hospital. (AP Photo/Raad Adayleh)

Seven years into the Syria conflict, with European and American doors increasingly shut to refugees and no signs of peace in Syria, neighboring countries like Jordan are cutting resources for Syrians, saying they cannot even afford to take care of their own people.

While Eman was in the operating room, another Syrian mother in Amman tried to keep her 12-year-old son Tamer from moving too much, afraid that his lips and hands would turn blue.

She fled the Damascus suburb of eastern Ghouta on the first day of the chemical attacks in 2013.

"They started at 3 a.m. and I left at 8 in the morning," she said of the attacks, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of repercussions for her family members in Syria. She brought her three boys, including a two-week-old baby, to Jordan.

In this March 5, 2018 photo, Syrian refugee Sara al-Matoura, watches through a window at her one-year-old daughter Eman's chest heaving up and down under a tangle of medical wires at a hospital in Amman, Jordan. Eman, who has a heart defect, received a life-saving pro bono surgery from doctors sent by the Vatican's Bambino Gesu Hospital. (AP Photo/Raad Adayleh)

Tamer, her second son, also has a congenital heart defect. When he moves too much, he loses his breath and turns blue.

Children with his condition should receive an operation at age five or six, according to Dr. Iyad al-Ammouri, pediatric cardiologist at the University of Jordan Hospital.

But Tamer's final surgery costs up to $28,000, far more than his mother can afford. She supports her sons alone, with her husband still trapped in Syria.

Jordan used to subsidize Syrians' fees at government health facilities, so they paid the same as uninsured Jordanians. But the subsidies were cancelled in February, meaning refugees must pay two to five times more for life-saving interventions.

In this February 22, 2018 photo, one-year-old Syrian refugee Eman is held by her mother, Sara al-Matoura, as they pose in their home in Jerash, Jordan. On Monday, March 5, 2018, Eman, who has a heart defect, received a life-saving pro bono surgery from doctors sent by the Vatican's Bambino Gesu Hospital. (AP Photo/Raad Adayleh)

Meanwhile, severe conditions like cancer and heart disease are subject to a special doctors' committee that sifts through hundreds of cases each month, deciding which few to assist based on criteria including vulnerability, prognosis and cost.

Late-stage cancer patients are typically offered palliative care. Expensive surgeries like Eman's, which would have cost $21,000, are also delayed.

"Of course people come back month after month and apply again, because they are desperate," said Dr. Adam Musa, a U.N. public health officer who sits on the committee. "It's painful."

In January, 60 out of 143 refugee applications for emergency help were approved. The United Nations gave them approximately $2,000 each. There wasn't enough funding for the rest, Musa said.

In this March 6, 2018 photo, Syrian refugee Younis al-Hariri, 8, rests his head on the lap of his mother, Ridaa al-Hariri, at their home in Amman Jordan. (AP Photo/Raad Adayleh)

Younis al-Hariri, an eight-year-old from Daraa, is one of those unfunded cases.

His mother, Ridaa, said he was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis and other liver conditions four years ago, and now needs a $565,000 transplant. She already owes $18,000 to Jordanian hospitals for dialysis, blood transfusions and hospital stays.

Al-Hariri's uncle, Hassan al-Turkmani, also needs surgery for his two hands, paralyzed in clenched fists from months of electric shock torture in Syrian prisons. Jagged scars run down his thin arms. The 32-year-old father of four hasn't been able to open his hands for seven years. The operation would cost $3,100 per finger.

"There is no mercy here," al-Turkmani said.

In this March 6, 2018 photo, Syrian refugee Hassan al-Turkmani, is photographed at his home in Amman, Jordan. Al-Turkmani needs surgery for his two hands, paralyzed in clenched fists from months of electric shock torture in Syrian prisons. (AP Photo/Raad Adayleh)

A senior Jordanian government official said health subsidies were cut because of an economic crisis. Syrian refugees are now paying health fees comparable to those charged to Jordanians, he said. Jordan remains on "high moral ground" for hosting the refugees at all, said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity in line with briefing regulations.

Across the region, donor fatigue and decreased host country support have left millions of refugees on the edge of survival, even pushing some to return to Syria.

The U.N. refugee agency spent $51 million on 84,000 life-saving cases in Lebanon last year, yet could not cover most cancer cases with poor prognoses, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or dialysis.

"There are very few NGOs that are able to provide support for some of these cases and we know that people have taken difficult decisions to return to Syria to access dialysis or cancer care," said Dr. Michael Woodman, senior public health officer in the UNHCR's Beirut office.

In this March 6, 2018 photo, Syrian refugee Younis al-Hariri, 8, looks at a mobile phone in his home in Amman Jordan. (AP Photo/Raad Adayleh)

Bambino Gesu got involved at the request of Pope Frances, said Dr. Fiore S. Iorio, who operated on Eman.

Iorio said he and his colleagues were also compelled by a "moral obligation to help these unfortunate children," either through surgery or by training Jordanian colleagues.

The U.N. refugee agency helped pay for the hospital expenses.

After Eman's surgery, her parents watched her breathe, her chest covered with bandages and wires, rising and failing in rhythm with the beeping monitor.

Doctors told them she would likely need another, more complicated surgery in two to five years.

"I don't know where we will get the money then," al-Matoura said. "But thank God for healing her today."