Under fire for the worst privacy debacle in his company's history, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg batted away often-aggressive questioning Tuesday from lawmakers who accused him of failing to protect the personal information of millions of Americans from Russians intent on upsetting the U.S. election.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg arrives to testify before a joint hearing of the Commerce and Judiciary Committees on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, April 10, 2018, about the use of Facebook data to target American voters in the 2016 election. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

During some five hours of Senate questioning, Zuckerberg apologized several times for Facebook failures, disclosed that his company was "working with" special counsel Robert Mueller in the federal probe of Russian election interference and said it was working hard to change its own operations after the harvesting of users' private data by a data-mining company affiliated with Donald Trump's campaign.

Click to Gallery

Under fire for the worst privacy debacle in his company's history, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg batted away often-aggressive questioning Tuesday from lawmakers who accused him of failing to protect the personal information of millions of Americans from Russians intent on upsetting the U.S. election.

During some five hours of Senate questioning, Zuckerberg apologized several times for Facebook failures, disclosed that his company was "working with" special counsel Robert Mueller in the federal probe of Russian election interference and said it was working hard to change its own operations after the harvesting of users' private data by a data-mining company affiliated with Donald Trump's campaign.

In all, he skated largely unharmed through his first day of congressional testimony. He'll face House questioners Wednesday.

At times, he showed plenty of steel. After a round of aggressive questioning about Facebook's alleged political bias from Sen. Ted Cruz, for instance, Zuckerberg grinned and almost chuckled. "That was pretty good," he said of the exchange with Cruz.

Earlier this year Mueller charged 13 Russian individuals and three Russian companies in a plot to interfere in the 2016 presidential election through a social media propaganda effort that included online ad purchases using U.S. aliases and politicking on U.S. soil. A number of the Russian ads were on Facebook.

Separately, the company began alerting some of its users that their data was gathered by Cambridge Analytica. A notification that appeared on Facebook for some users Tuesday told them that "one of your friends" used Facebook to log into a now-banned personality quiz app called "This Is Your Digital Life." The notice says the app misused the information, including public profiles, page likes, birthdays and current cities, by sharing it with Cambridge Analytica.

Seemingly unimpressed, Republican Sen. John Thune of South Dakota said Zuckerberg's company had a 14-year history of apologizing for "ill-advised decisions" related to user privacy. "How is today's apology different?" Thune asked.

"We have made a lot of mistakes in running the company," Zuckerberg conceded, and Facebook must work harder at ensuring the tools it creates are used in "good and healthy" ways.

The controversy has brought a flood of bad publicity and sent the company's stock value plunging, but Zuckerberg seemed to achieve a measure of success in countering that: Facebook shares surged 4.5 percent for the day, the biggest gain in two years.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies before a joint hearing of the Commerce and Judiciary Committees on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, April 10, 2018, about the use of Facebook data to target American voters in the 2016 election. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

In all, he skated largely unharmed through his first day of congressional testimony. He'll face House questioners Wednesday.

The 33-year-old founder of the world's best-known social media giant appeared in a suit and tie, a departure from the T-shirt he's famous for wearing in public as well as in private. Even so, his youth cast a sharp contrast with his often-elderly, gray-haired Senate inquisitors. And the enormous complexity of the social network he created at times defeated the attempts of legislators to hammer him on Facebook's specific failures and how to fix them.

The stakes are high for both Zuckerberg and his company. Facebook has been reeling from its worst-ever privacy failure following revelations last month that the political data-mining firm Cambridge Analytica, which was affiliated with Trump's 2016 campaign, improperly scooped up data on some 87 million users. Zuckerberg has been on an apology tour for most of the past two weeks, culminating in his congressional appearance Tuesday.

Although shaky at times, Zuckerberg seemed to gain confidence as the day progressed. An iconic figure as a billionaire entrepreneur who changed the way people around the world relate to each other, he made a point of repeatedly referring back to the Harvard dorm room where he said Facebook was brought to life.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg arrives to testify before a joint hearing of the Commerce and Judiciary Committees on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, April 10, 2018, about the use of Facebook data to target American voters in the 2016 election. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

At times, he showed plenty of steel. After a round of aggressive questioning about Facebook's alleged political bias from Sen. Ted Cruz, for instance, Zuckerberg grinned and almost chuckled. "That was pretty good," he said of the exchange with Cruz.

For the most part, his careful but generally straightforward answers, steeped in the sometimes arcane details of Facebook's underlying functions, often deflected aggressive questioning. When the going got tough, Zuckerberg was able to fall back on: "Our team should follow up with you on that, Senator."

As a result, he found it relatively easy to return to familiar talking points: Facebook made mistakes, he and his executives are very sorry, and they're working very hard to correct the problems and safeguard the users' data.

As for the federal Russia probe that has occupied much of Washington's attention for months, he said he had not been interviewed by special counsel Mueller's team, but "I know we're working with them." He offered no details, citing a concern about confidentiality rules of the investigation.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies before a joint hearing of the Commerce and Judiciary Committees on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, April 10, 2018, about the use of Facebook data to target American voters in the 2016 election. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Earlier this year Mueller charged 13 Russian individuals and three Russian companies in a plot to interfere in the 2016 presidential election through a social media propaganda effort that included online ad purchases using U.S. aliases and politicking on U.S. soil. A number of the Russian ads were on Facebook.

Much of the effort was aimed at denigrating Democrat Hillary Clinton and thereby helping Republican Trump, or simply encouraging divisiveness and undercutting faith in the U.S. system.

Zuckerberg said Facebook had been led to believe Cambridge Analytica had deleted the user data it had harvested and that had been "clearly a mistake." He said Facebook had considered the data collection "a closed case" and had not alerted the Federal Trade Commission. He assured senators the company would handle the situation differently today.

Life-sized cutouts depicting Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wearing "Fix Fakebook" T-shirts are displayed by advocacy group, Avaaz, on the South East Lawn of the Capitol on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, April 10, 2018, ahead of Zuckerberg's appearance before a Senate Judiciary and Commerce Committees joint hearing. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Separately, the company began alerting some of its users that their data was gathered by Cambridge Analytica. A notification that appeared on Facebook for some users Tuesday told them that "one of your friends" used Facebook to log into a now-banned personality quiz app called "This Is Your Digital Life." The notice says the app misused the information, including public profiles, page likes, birthdays and current cities, by sharing it with Cambridge Analytica.

In the hearings, Zuckerberg is trying to both restore public trust in his company and stave off federal regulations that some lawmakers have floated.

Democrat Bill Nelson of Florida said he believes Zuckerberg was taking the congressional hearings seriously "because he knows there is going to be a hard look at regulation."

Republicans have yet to get behind any legislation, but that could change.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg pauses while testifying before a joint hearing of the Commerce and Judiciary Committees on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, April 10, 2018, about the use of Facebook data to target American voters in the 2016 election. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., asked Zuckerberg if he would be willing to work with lawmakers to examine what "regulations you think are necessary in your industry."

Absolutely, Zuckerberg responded, saying later in an exchange with Sen. Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, that "I'm not the type of person who thinks that all regulation is bad."

Ahead of the hearing, John Cornyn of Texas, the No. 2 Republican in the Senate, said, "This is a serious matter, and I think people expect us to take action."

At the hearing, Zuckerberg said: "We didn't take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake. It was my mistake, and I'm sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I'm responsible for what happens here."

He outlined steps the company has taken to restrict outsiders' access to people's personal information. He also said the company is investigating every app that had access to a large amount of information before the company moved to prevent such access in 2014 — actions that came too late in the Cambridge Analytica case.

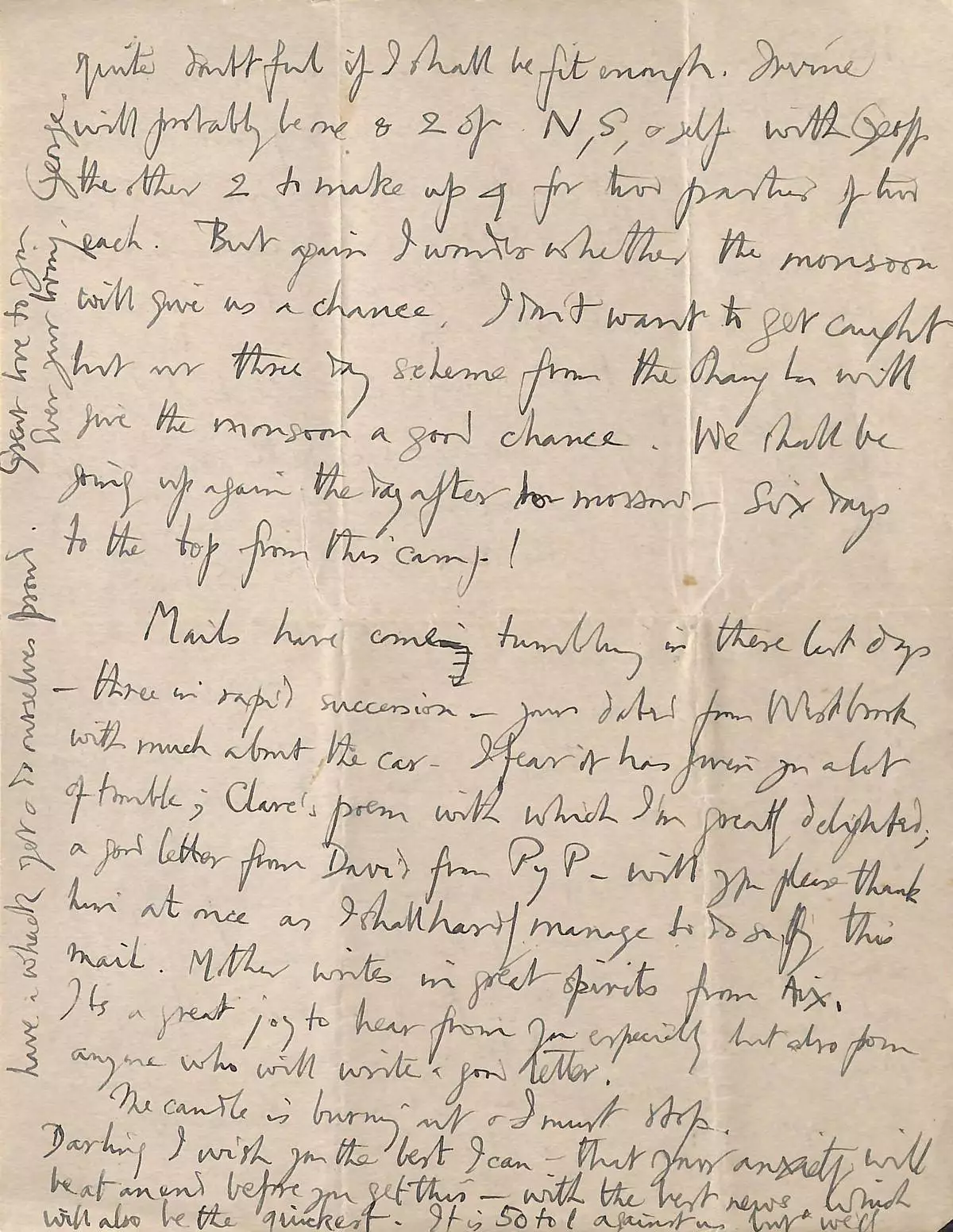

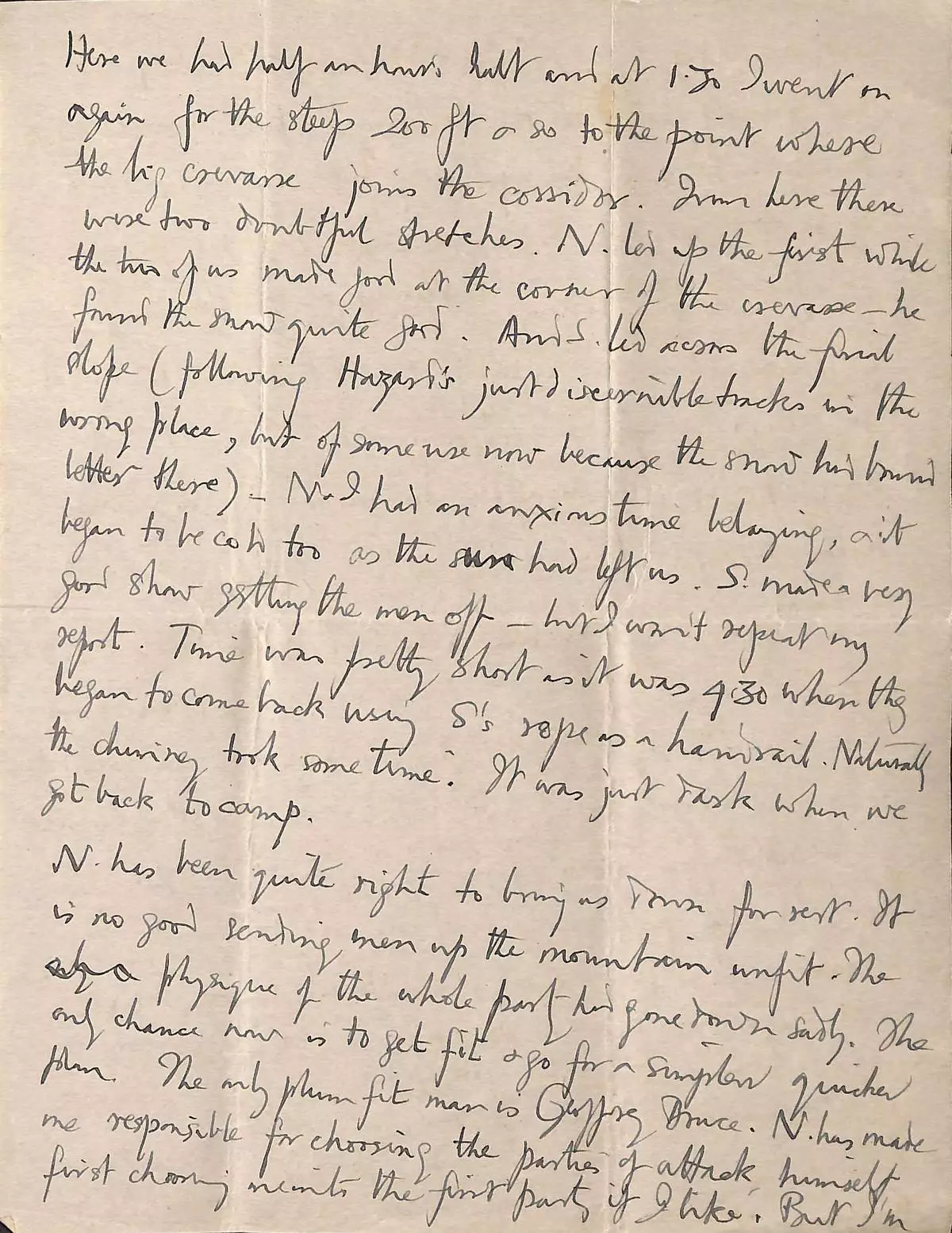

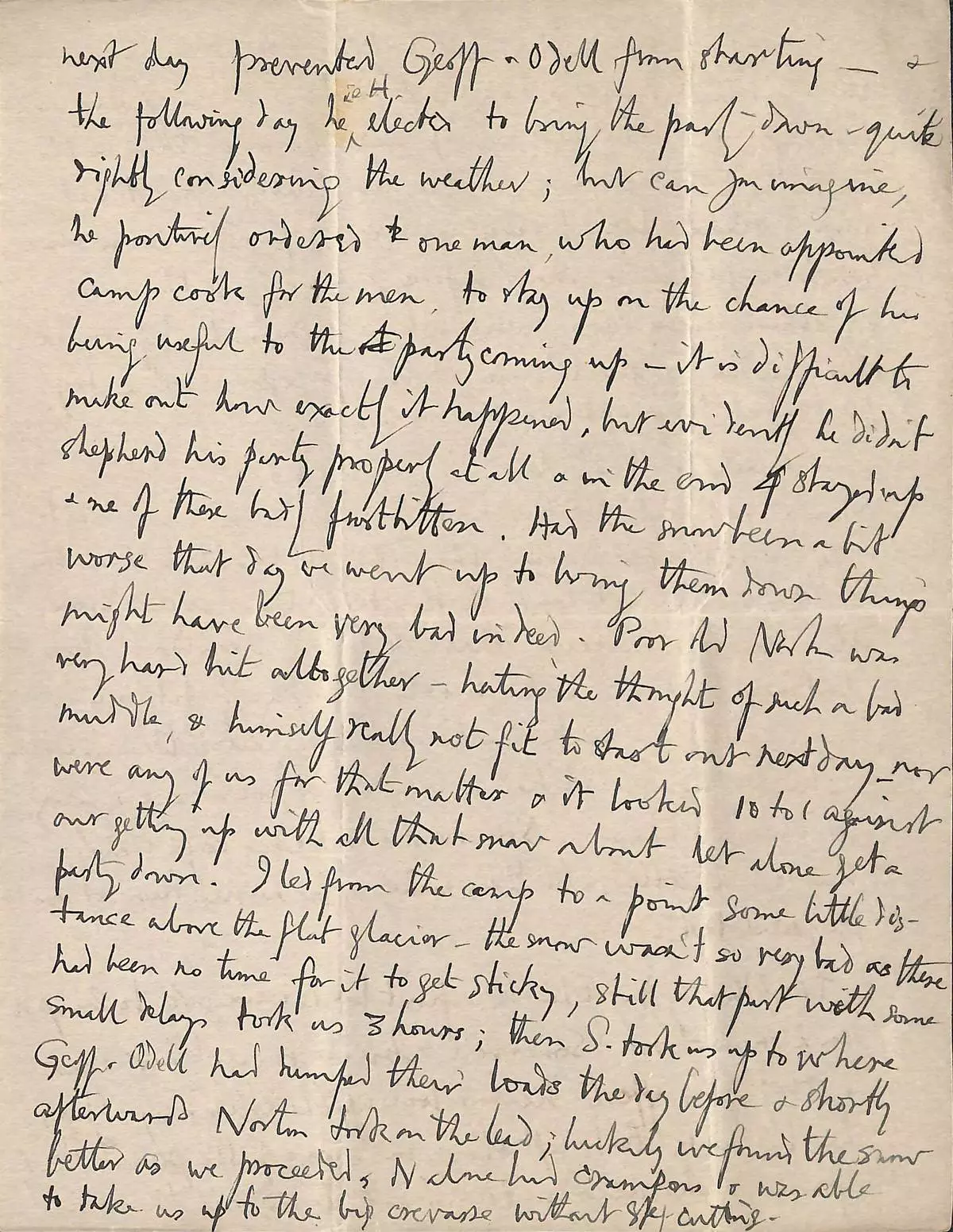

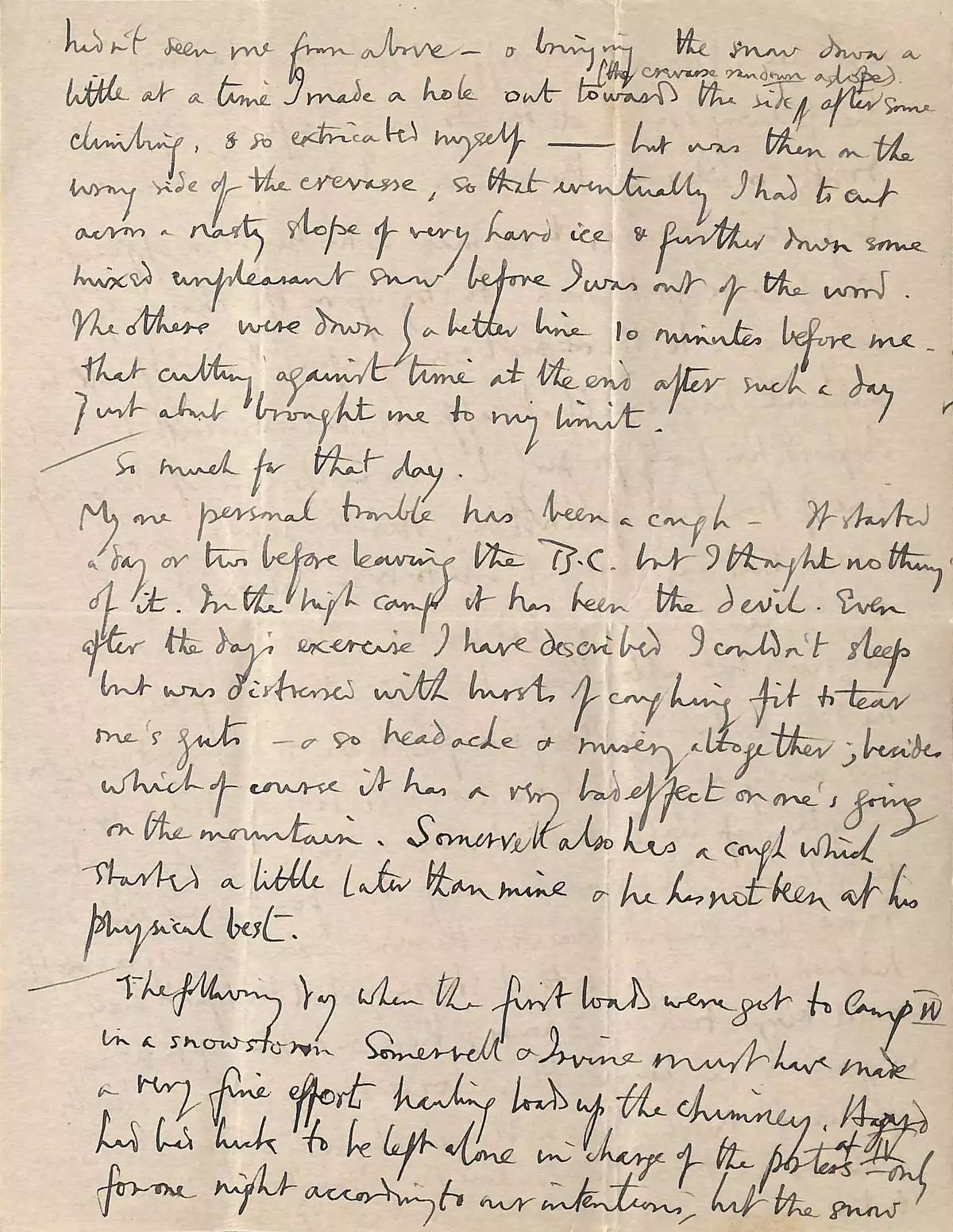

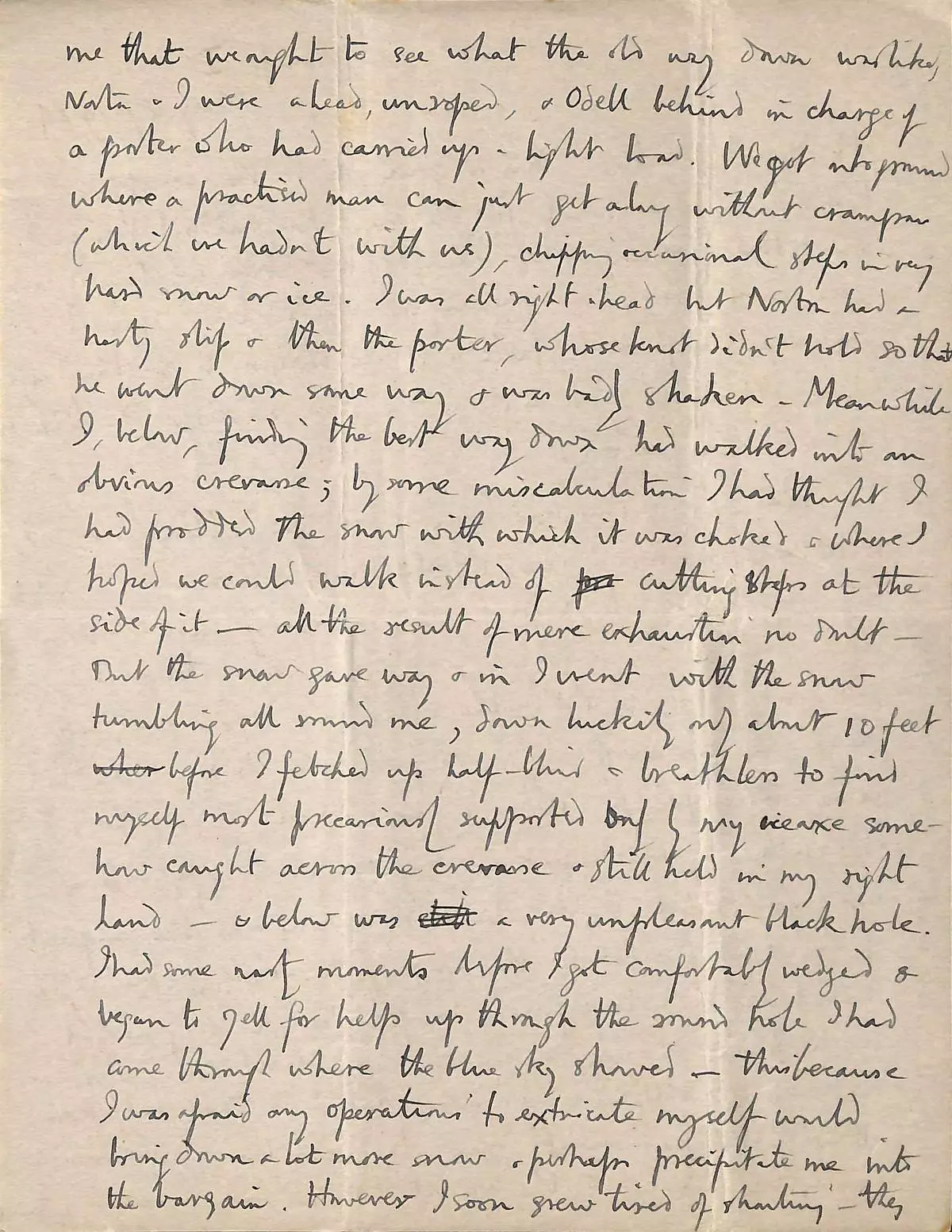

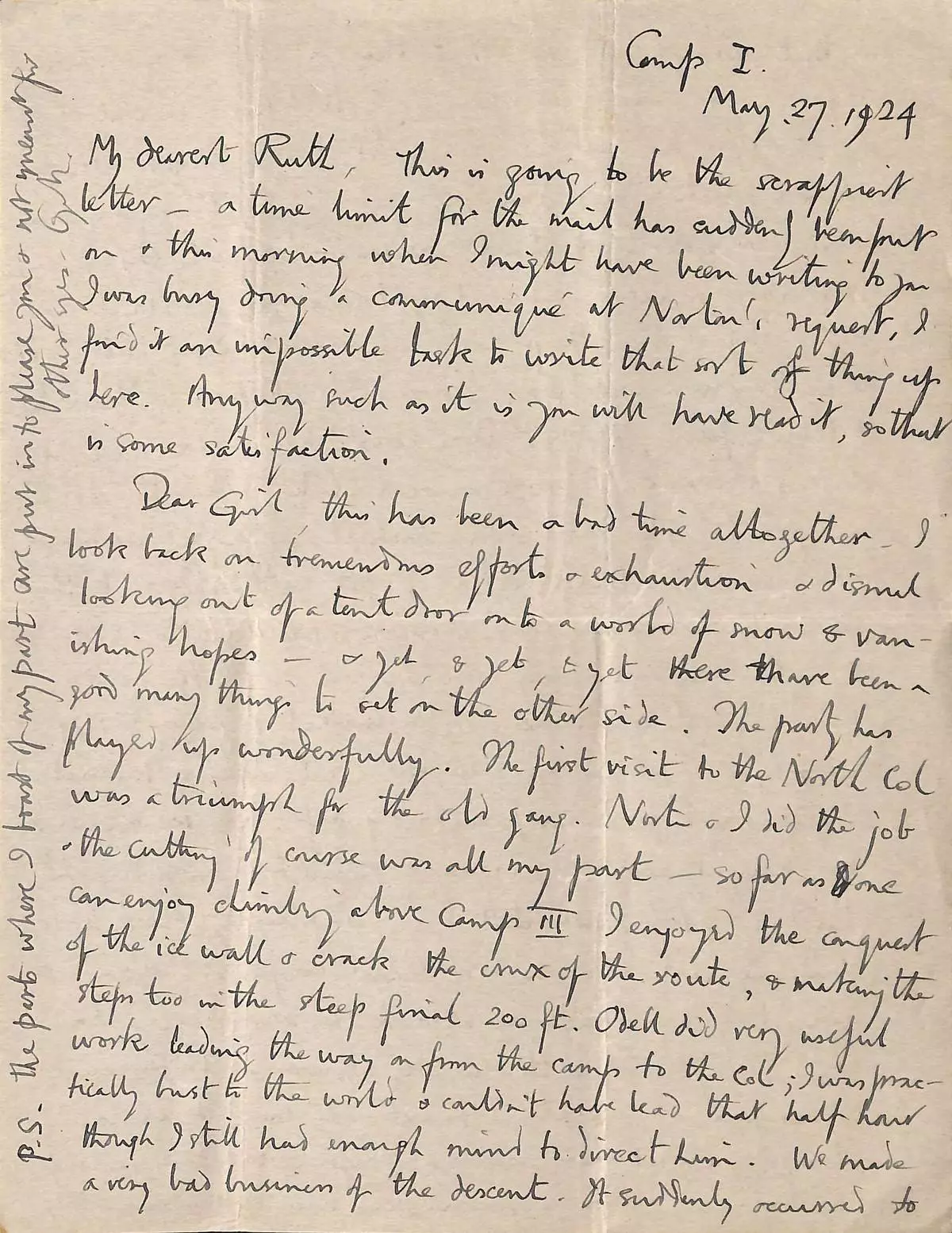

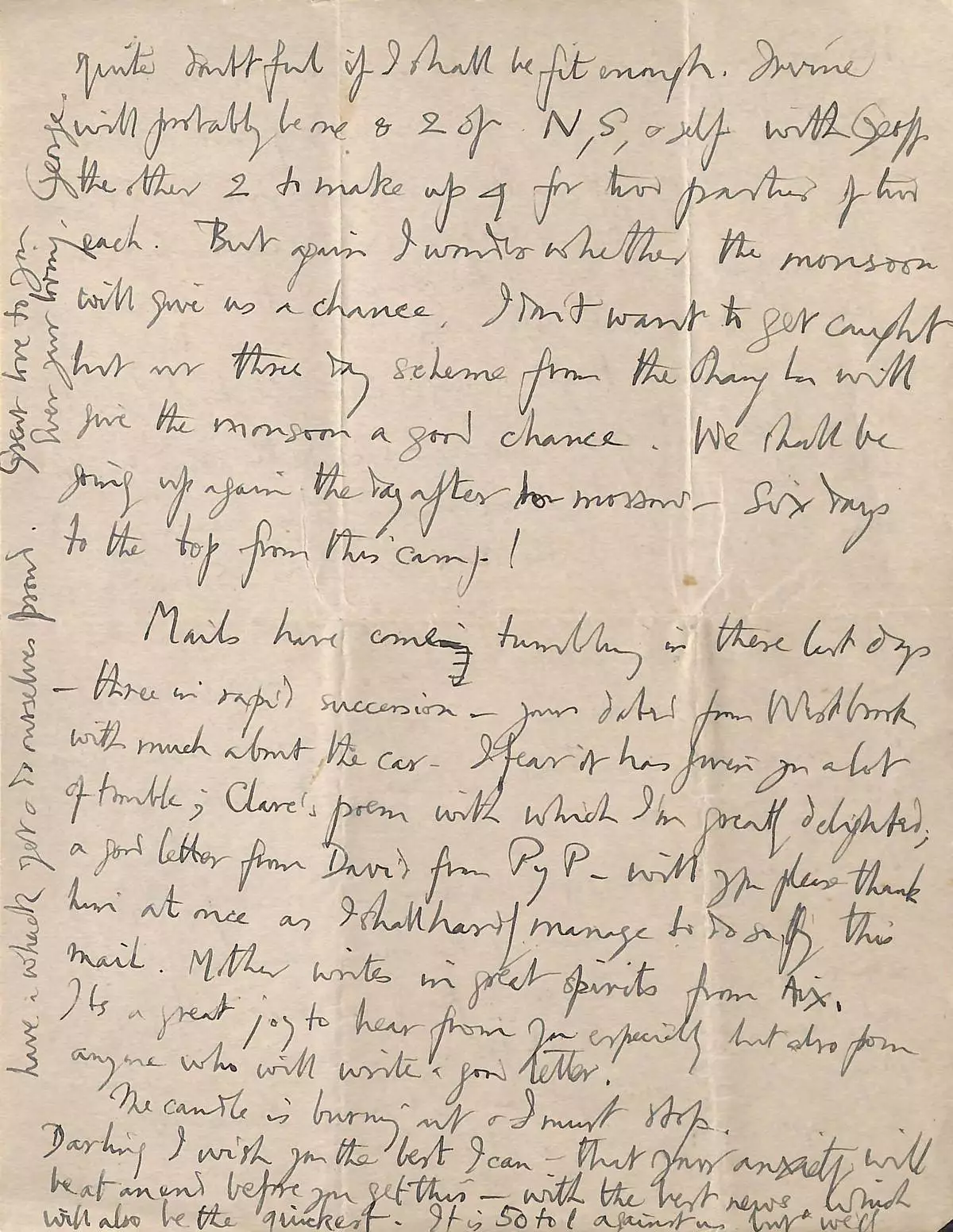

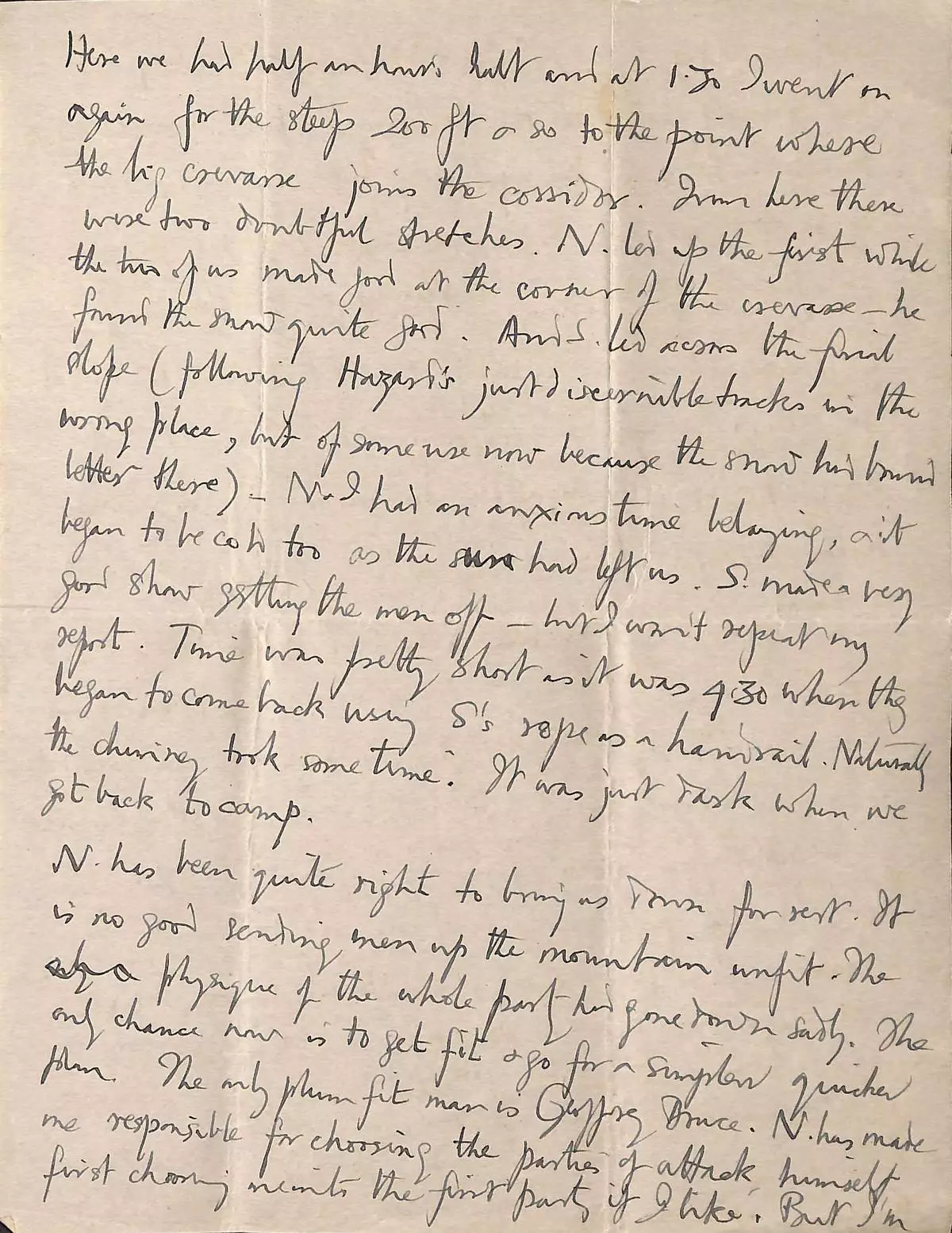

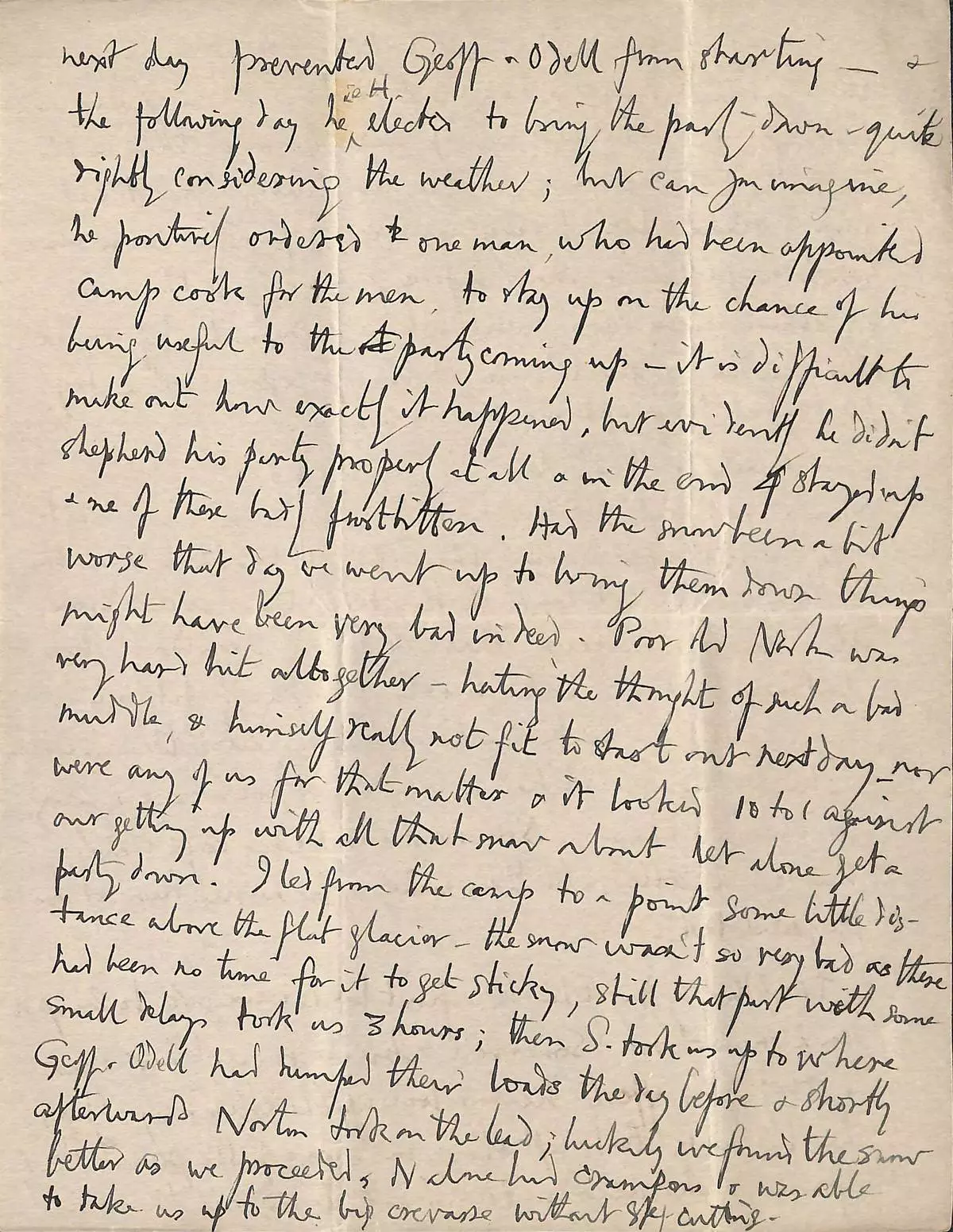

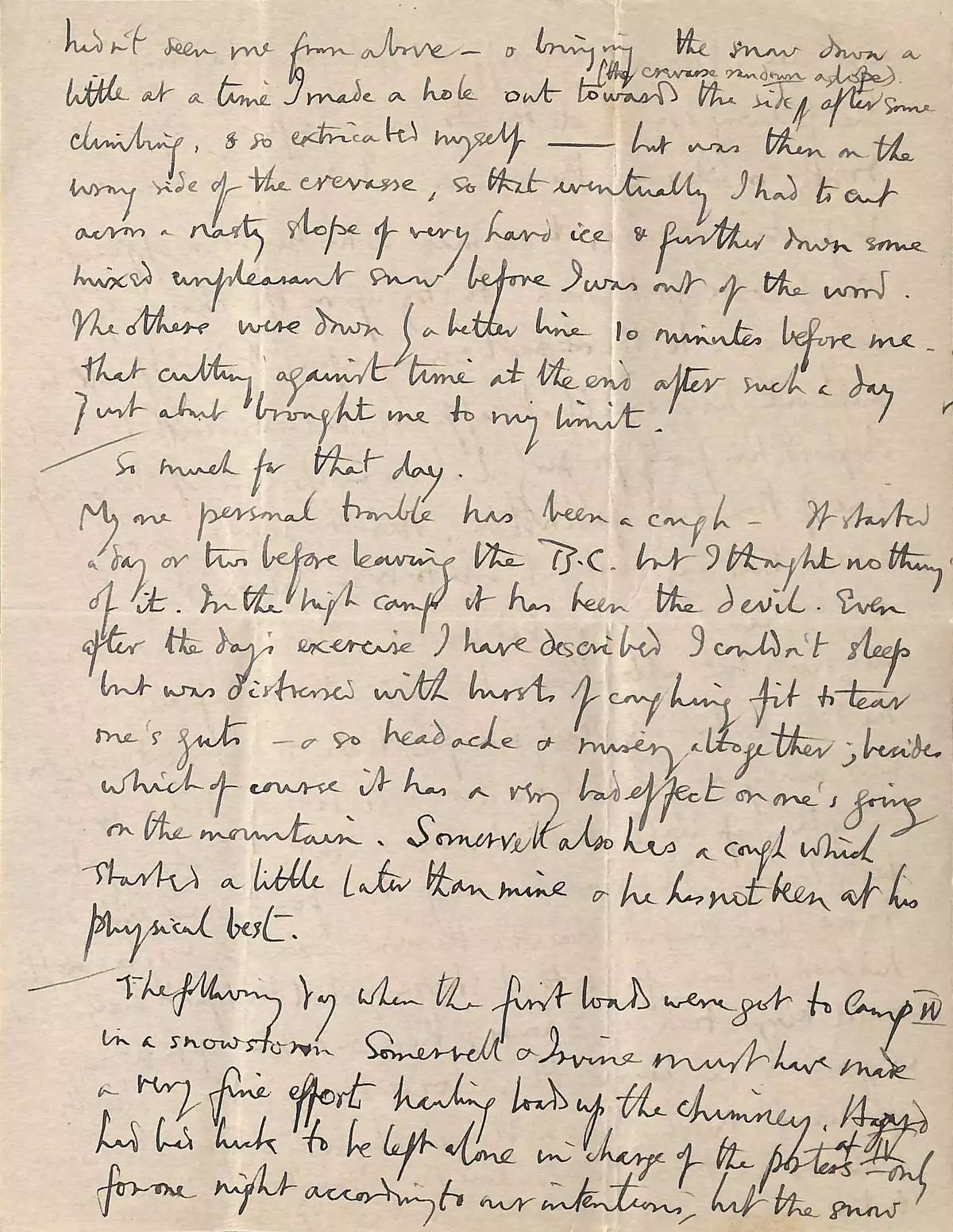

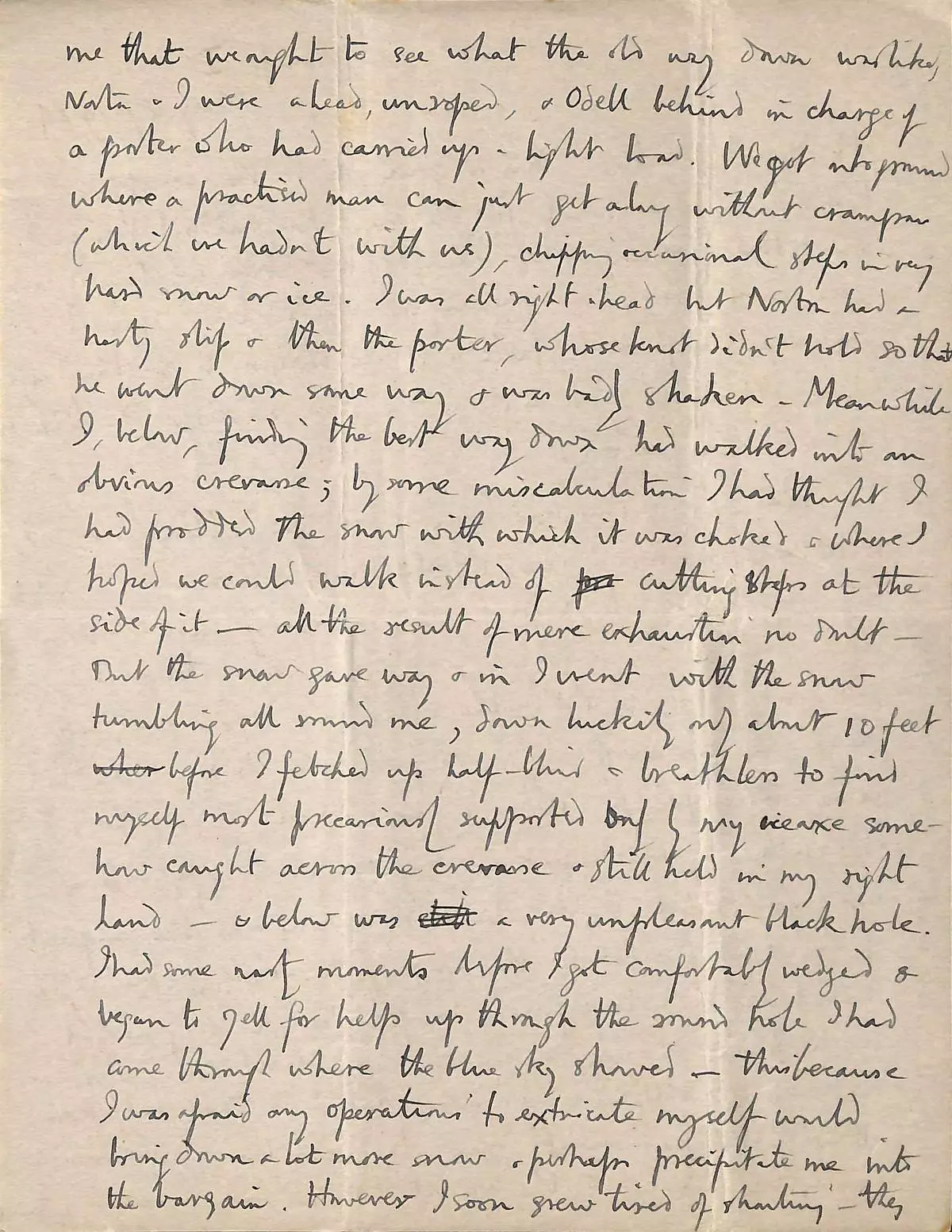

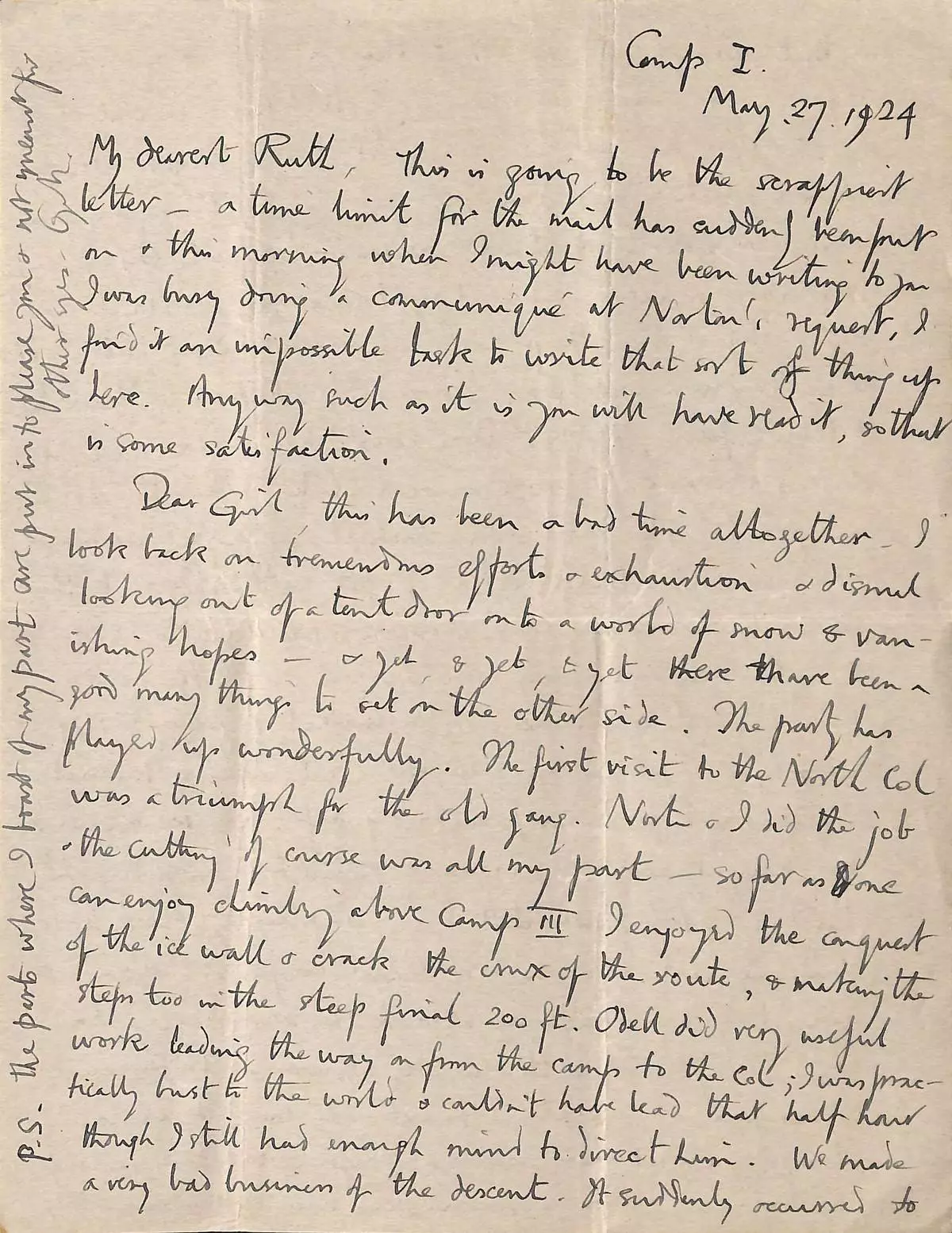

In his final letter to his wife before he vanished on Mount Everest a century ago, George Mallory tried to ease her worries even as he said his chances of reaching the world's highest peak were “50 to 1 against us."

The letter, digitized for the first time and published online Monday by his Cambridge University alma mater, expressed a mix of optimism, exhaustion and the difficulties his expedition encountered on their quest to be the first party to conquer the peak.

“Darling I wish you the best I can — that your anxiety will be at an end before you get this — with the best news," he wrote to Ruth Mallory on May 27, 1924 from Camp I. “It is 50 to 1 against us but we’ll have a whack yet & do ourselves proud.”

It remains a mystery whether Mallory, who once famously said he wanted to conquer Everest “because it’s there,” and climbing partner Andrew Irvine reached the summit and died on the way down or never made it that far. Mallory’s body was found 75 years later far below the peak, but Irvine's has never been located.

The first documented ascent came nearly three decades later when New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Nepalese Sherpa Tenzing Norgay scaled the mountain on May 29, 1953.

Magdalene College posted the letters online to mark the centenary of Mallory's ill-fated attempt to stand atop the world. The collection, which had previously been available to researchers, also includes letters he wrote from the battlefront in World War I and correspondence he received from others, including his wife.

The only surviving letter his wife wrote from England during the expedition was sent as his party sailed toward Bombay. It recounts a recent snowstorm, how her bank account was overdrawn and how she fell off a ladder before telling him how much she missed him.

“I know I have rather often been cross and not nice and I am very sorry but the bottom reason has nearly always been because I was unhappy at getting so little of you," Ruth Mallory wrote on March 3, 1924. “I know it is pretty stupid to spoil the times I do have you for those when I don’t.”

In his final six-page correspondence to his wife, addressed to “My dearest Ruth," George Mallory speaks of trials and triumphs as the party slowly made its way up the mountain, setting up higher camps and then retreating to lower elevation to recover.

“This has been a bad time altogether,” Mallory wrote 12 days before he was last seen alive. “I look back on tremendous efforts & exhaustion & dismal looking out of a tent door and onto a world of snow & vanishing hopes — & yet, & yet, & yet there have been a good many things to set on the other side.”

Mallory said he had a nagging cough “fit to tear one’s guts” that left him sleepless and made climbing difficult. He described a near-death plunge into a crevasse when he failed to detect it beneath a blanket of snow.

“In I went with the snow tumbling all around me, down luckily only about 10 feet before I fetched up half-blind & breathless to find myself most precariously supported only by my ice ax somehow caught across the crevasse & still held in my right hand,” he said. “Below was a very unpleasant black hole.”

Mallory said only one member of the party remained “plum fit” and they planned to rest up for two days before pushing for the summit, which was expected to take six days.

Mallory and Irvine were last seen alive June 8, 1924 when they were said to be still going strong some 900 feet (274 meters) beneath the 29,035 feet (8,850 meters) summit. Mallory’s body was found at 26,700 feet (8,138 meters).

A group of mountaineers who tried in 2007 to reconstruct Mallory's ascent were unable to determine if the pair made it to the top.

“I still believe the possibility is there they made it to the top, but it is very unlikely,” said Conrad Anker, who participated in a documentary recreating the climb and who had discovered Mallory's body in 1999.

In Mallory's final letter to his wife, he says, “the candle is burning out & I must stop.” He signs off: “Great love to you. Ever your loving, George.”

This is an undated photo provided by Magdalene College Cambridge on Monday, April 22, 2024 of part of the final letter that mountaineer George Mallory wrote to his wife before he vanished on Mount Everest a century ago. The letter has been digitalized. The letter was published on Monday by Mallory's Cambridge University college. In it, he tried to ease her worries though he said his chances of reaching the world’s highest peak were “50 to 1 against us.” (Reproduced with Permission of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge via AP)

This is an undated photo provided by Magdalene College Cambridge on Monday, April 22, 2024 of part of the final letter that mountaineer George Mallory wrote to his wife before he vanished on Mount Everest a century ago. The letter has been digitalized. The letter was published on Monday by Mallory's Cambridge University college. In it, he tried to ease her worries though he said his chances of reaching the world’s highest peak were “50 to 1 against us.” (Reproduced with Permission of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge via AP)

This is an undated photo provided by Magdalene College Cambridge on Monday, April 22, 2024 of part of the final letter that mountaineer George Mallory wrote to his wife before he vanished on Mount Everest a century ago. The letter has been digitalized. The letter was published on Monday by Mallory's Cambridge University college. In it, he tried to ease her worries though he said his chances of reaching the world’s highest peak were “50 to 1 against us.” (Reproduced with Permission of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge via AP)

This is an undated photo provided by Magdalene College Cambridge on Monday, April 22, 2024 of part of the final letter that mountaineer George Mallory wrote to his wife before he vanished on Mount Everest a century ago. The letter has been digitalized. The letter was published on Monday by Mallory's Cambridge University college. In it, he tried to ease her worries though he said his chances of reaching the world’s highest peak were “50 to 1 against us.” (Reproduced with Permission of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge via AP)

This is an undated photo provided by Magdalene College Cambridge on Monday, April 22, 2024 of part of the final letter that mountaineer George Mallory wrote to his wife before he vanished on Mount Everest a century ago. The letter has been digitalized. The letter was published on Monday by Mallory's Cambridge University college. In it, he tried to ease her worries though he said his chances of reaching the world’s highest peak were “50 to 1 against us.” (Reproduced with Permission of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge via AP)

This is an undated photo provided by Magdalene College Cambridge on Monday, April 22, 2024 of part of the final letter that mountaineer George Mallory wrote to his wife before he vanished on Mount Everest a century ago. The letter has been digitalized. The letter was published on Monday by Mallory's Cambridge University college. In it, he tried to ease her worries though he said his chances of reaching the world’s highest peak were “50 to 1 against us.” (Reproduced with Permission of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge via AP)

FILE - British mountaineers George Mallory is seen with Andrew Irvine at the base camp in Nepal, both members of the Mount Everest expeditions 1922 and 1924, as they get ready to climb the peak of Mount Everest June 1924. It is the last image of the men before they disappeared in the mountain. George Mallory’s final letter to his wife before he vanished on Mount Everest a century ago tried to ease her worries though he said his chances of reaching the world’s highest peak were “50 to 1 against us.” (AP Photo, File)