The Trump administration's move to separate immigrant parents from their children on the U.S.-Mexico border has grabbed attention around the world, drawn scorn from human-rights organizations and overtaken the immigration debate in Congress.

FILE - In this June 1, 2018, file photo, children hold signs during a demonstration in front of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement offices in Miramar, Fla. The Trump administration's move to separate immigrant parents from their children on the U.S.-Mexico border has turned into a full-blown crisis in recent weeks, drawing denunciation from the United Nations, Roman Catholic bishops and countless humanitarian groups. (AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee, File)

It's also a situation that has been brewing since the week President Donald Trump took office, when he issued his first order signaling a tougher approach to asylum-seekers. Since then, the administration has been steadily eroding protections for immigrant children and families.

"They're willing to risk harm to a child being traumatized, separated from a parent and sitting in federal detention by themselves, in order to reach a larger policy goal of deterrence," said Jennifer Podkul, director of policy at Kids in Need of Defense, which represents children in immigration court.

To those who work with immigrants, the parents' plight was heralded by a series of measures making it harder for kids arriving on the border to get released from government custody and to seek legal status here.

The administration has said the changes are needed to deter immigrants from coming here illegally. But a backlash is mounting, fueled by reports of children being taken from mothers and distraught toddlers and elementary school age children asking, through tears, when they can see their parents.

FILE - In this June 15, 2018 file photo, Chris Olson, of Lake Wallenpaupack, Pa., holds a sign outside Lackawanna College where U.S. Attorney Jeff Sessions spoke on immigration policy and law enforcement actions, in Scranton, Pa. (Butch Comegys/The Times-Tribune via AP, File)

About 2,000 children had been separated from their families over a six-week period ending in May, administration officials said Friday.

Among the parents caught up in the new rules is 29-year-old Vilma Aracely Lopez Juc de Coc, who fled her home in a remote Guatemalan village after her husband was beaten to death in February, according to advocates. When she reached the Texas border with her 11-year-old son in May, he was taken from her by border agents, she said.

Her eyes swollen, she cried when she asked a paralegal what she most wanted to know: When could she see her son again?

"She did not know what was going on," said paralegal Georgina Guzman, recalling their conversation at a federal courthouse in McAllen, Texas.

Similar scenarios play out on a daily basis in federal courtrooms in Texas and Arizona, where dozens of immigrant parents appear on charges of entering the country illegally after traveling up from Central America. More than the legal outcome of their cases, their advocates say, they're worried about their children.

Since Trump's inauguration, the administration has issued at least half a dozen orders and changes affecting immigrant children, many of them obscure revisions. The cumulative effect is a dramatic alteration of immigration policy and practice.

The measures require a senior government official to sign off on the release of children from secure shelters and allow immigration enforcement agents access to information about sponsors who sign up to take the children out of government custody and care for them.

The crackdown expanded in April, when the administration announced a "zero tolerance" policy on the border to prosecute immigrants for entering the country illegally in the hopes they could be quickly deported and that the swift deportations would prevent more people from coming.

Parents are now being arrested and placed in quick federal court proceedings near the border. Since children cannot be jailed in federal prisons, they're placed in shelters that have long existed for unaccompanied immigrant children arriving on the border alone.

The administration insists the new rules are necessary to send a message to immigrants.

"Look, I hope that we don't have to separate any more children from any more adults," Attorney General Jeff Sessions said last week. "But there's only one way to ensure that is the case: It's for people to stop smuggling children illegally. Stop crossing the border illegally with your children. Apply to enter lawfully. Wait your turn."

Immigration on the southwest border has remained high since the zero-tolerance policies took effect. Border agents made more than 50,000 arrests in May, up slightly from a month earlier and more than twice the number in May 2017. About a quarter of arrests were families traveling with children.

In addition to those trying to cross on their own, large crowds of immigrants are gathered at border crossings each day to seek asylum. Some wait days or weeks for a chance to speak with U.S. authorities. On a Texas border bridge, parents and children have been sleeping in sweltering heat for several days awaiting their turn.

Under U.S. law, most Mexican children are sent back across the border. Central American and other minors are taken into government custody before they are mostly released to sponsors in the United States.

The arrival of children fleeing violence in Central America is not new. President Barack Obama faced an even larger surge in border crossings that overflowed shelters and prompted the authorities to release many families. Nearly 60,000 children were placed in government-contracted shelters in the 2014 fiscal year.

Obama administration lawyers argued in federal court in Los Angeles against the separation of parents and children and in favor of keeping in family detention facilities those deemed ineligible for release.

Immigrant and children's advocates said the new measures are not only cruel but costly. They argued that children fleeing violence and persecution in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras will continue to come to the United States and remain in government custody longer, costing taxpayers more money.

The government pays more than $1 billion a year to care for unaccompanied immigrant children, Sessions has said.

In May 2014, the average length of stay for children in custody was 35 days. So far this fiscal year, it's taking 56 days for children to be released to sponsors — in most cases, their own relatives.

Many children were released to sponsors who did not have legal immigration status. That's yet another concern child advocates now have since the Trump administration is requiring fingerprints of sponsors and their household members and will turn that data over to the immigration agency in charge of deportations.

Advocates say the new information sharing might lead some parents to shy away from sponsoring their own children and ask others to do so, a situation that can lead to cases of trafficking or neglect.

Simon Sandoval-Moshenberg, legal director of the immigrant advocacy program at the Legal Aid Justice Center in Virginia, said he's never worked with immigrants who said U.S. policies influenced their decision to move. They are fleeing violence and persecution, and he doesn't see that changing even if the government deports parents.

"Look six months out from now," he said. "Are these moms going to stay in Guatemala? Hell no, they're going to come back looking for their kids."

WASHINGTON (AP) — For Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell and House Speaker Mike Johnson, the necessity of providing Ukraine with weapons and other aid as it fends off Russia's invasion is rooted in their earliest and most formative political memories.

McConnell, 82, tells the story of his father’s letters from Eastern Europe in 1945, at the end of World War II, when the foot soldier observed that the Russians were “going to be a big problem” before the communist takeover to come. Johnson, 30 years younger, came of age as the Cold War was ending.

As both men pushed their party this week to support a $95 billion aid package that sends support to Ukraine, as well as Israel, Taiwan and humanitarian missions, they labeled themselves “Reagan Republicans” an described the fight against Russian President Vladimir Putin in terms of U.S. strength and leadership. But the all-out effort to get the legislation through Congress left both of them grappling with an entirely new Republican Party shaped by former President Donald Trump.

While McConnell, R-Ky., and Johnson, R-La., took different approaches to handling Trump, the presumptive White House nominee in 2024, the struggle highlighted the fundamental battle within the GOP: Will conservatives continue their march toward Trump’s “America First” doctrine on foreign affairs or will they find the value in standing with America's allies? And is the GOP still the party of Ronald Reagan?

“I think we’re having an internal debate about that,” McConnell said in an interview with The Associated Press. “I’m a Reagan guy and I think today — at least on this episode — we turned the tables on the isolationists.”

Still, he acknowledged, “that doesn’t mean they’re going to go away forever.”

McConnell, in the twilight of his 18-year tenure as Republican leader, lauded a momentary victory Tuesday as a healthy showing of 31 Republicans voted for the foreign aid; that was nine more than had supported it in February. He said that was a trend in the right direction.

McConnell, who has been in the Senate since 1985, said passing the legislation was “one of the most important things I’ve ever dealt with where I had an impact."

But it wasn’t without cost.

He said last month he would step away from his job as leader next year after internal clashes over the money for Ukraine and the direction of the party.

For Johnson, just six months into his job as speaker, the political crosscurrents are even more difficult. He is clinging to his leadership post as right-wing Republicans threaten to oust him for putting the aid to Ukraine to a vote. While McConnell has embraced American leadership abroad his entire career, Johnson only recently gave complete support to the package.

Johnson has been careful not to portray passage as a triumph when a majority of his own House Republicans opposed the bill. He skipped a celebratory news conference afterward, describing it as “not a perfect piece of legislation” in brief remarks.

But he also borrowed terms popularized by Reagan, saying aggression from Russia, China and Iran “threatens the free world and it demands American leadership.”

“If we turn our backs right now, the consequences could be devastating,” he said.

Hard-line conservatives, including some who are threatening a snap vote on his leadership, are irate, saying the aid was vastly out of line with what Republican voters want. They condemned both Johnson and McConnell for supporting it.

“House Republican leadership sold out Americans and passed a bill that sends $95 billion to other countries,” said Republican Sen. Tommy Tuberville of Alabama, who opposed the bill. He said the legislation "undermines America's interests abroad and paves our nation's path to bankruptcy.”

Johnson has been lauded by much of Washington for doing what he called “the right thing" at a perilous moment for himself and the world.

“He is fundamentally an honorable person,” said Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., who brokered the negotiations and spent hours on the phone and in meetings with Johnson, McConnell and the White House.

Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, said Johnson and McConnell “both showed great resolve and backbone and true leadership at a time it was desperately needed.”

When McConnell began negotiations over President Joe Biden's initial aid request last year, he quickly set the terms for a deal. He and Schumer agreed to pair any aid for Ukraine with help for Israel, Schumer said, and McConnell demanded policy changes at the U.S. border with Mexico.

On McConnell's mind, he said, was that Trump was “unenthusiastic” about providing more aid to Kyiv. Yet McConnell, whose office displays a portrait of every Republican president since Reagan with the exception of Trump, had a virtually nonexistent relationship with the man he often refers to not by name, but simply as “the former president.”

Still, Trump would prove to hold powerful sway. When a deal on border security neared completion after months of work, Trump eviscerated the proposal as insufficient and a “gift” to Biden's reelection. Conservatives, including Johnson, rejected it out of hand.

With the border deal dead, McConnell pushed ahead with Schumer on the foreign aid, with the border policies stripped out, solidifying their unusual alliance. The Senate leaders met weekly throughout the negotiation.

“We disagreed on a whole lot, but we really stuck together,” Schumer said.

“We just persisted. We could not give up on this."

Meanwhile, a small group of GOP senators began working on an idea they thought could give Johnson some political wiggle room. Sens. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, Kevin Cramer of North Dakota and Markwayne Mullin of Oklahoma took an idea that Trump had raised — structuring the aid to Ukraine as a loan — and tried to make it reality.

Through a series of phone calls with Trump, several House members, as well as the speaker, they worked to structure roughly $9 billion in economic aid for Ukraine as forgivable loans — just as it was in the final package.

“Our approach this time was to make sure that the politics were set, meaning that President Trump is on board,” Mullin said.

The conversations culminated in Johnson making a quick jaunt to Florida, where he stood side by side with Trump at his Florida club just days before moving ahead with the Ukraine legislation in the House.

It was all enough, with Democratic help, to get the bill across the finish line. The legislation, which Biden signed into law on Wednesday, included some revisions from the Senate bill, including the loan structure and a provision to seize frozen Russian central bank assets to rebuild Ukraine. Nine GOP senators who had opposed the first version of the bill swung to “yes” largely because of the changes Johnson had made.

The result was a strong showing for the foreign aid in the Senate, even though the decision could prove costly for Johnson.

What comes next on Ukraine is anyone's guess.

While the $61 billion for Ukraine in the package is expected to help the country withstand Moscow's offensive this year, more assistance will surely be needed. Republicans, exhausted after a grueling fight, largely shrugged off questions about the future.

“This one wasn’t easy,” Mullin said.

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

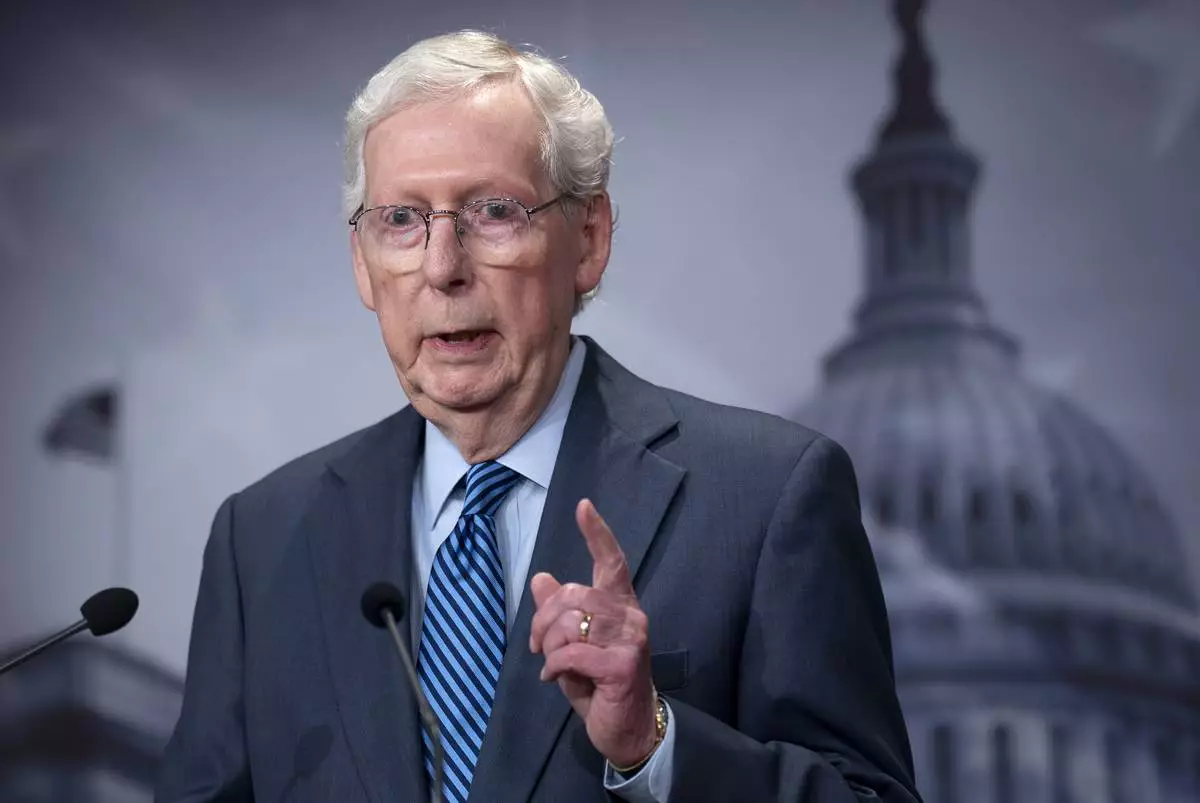

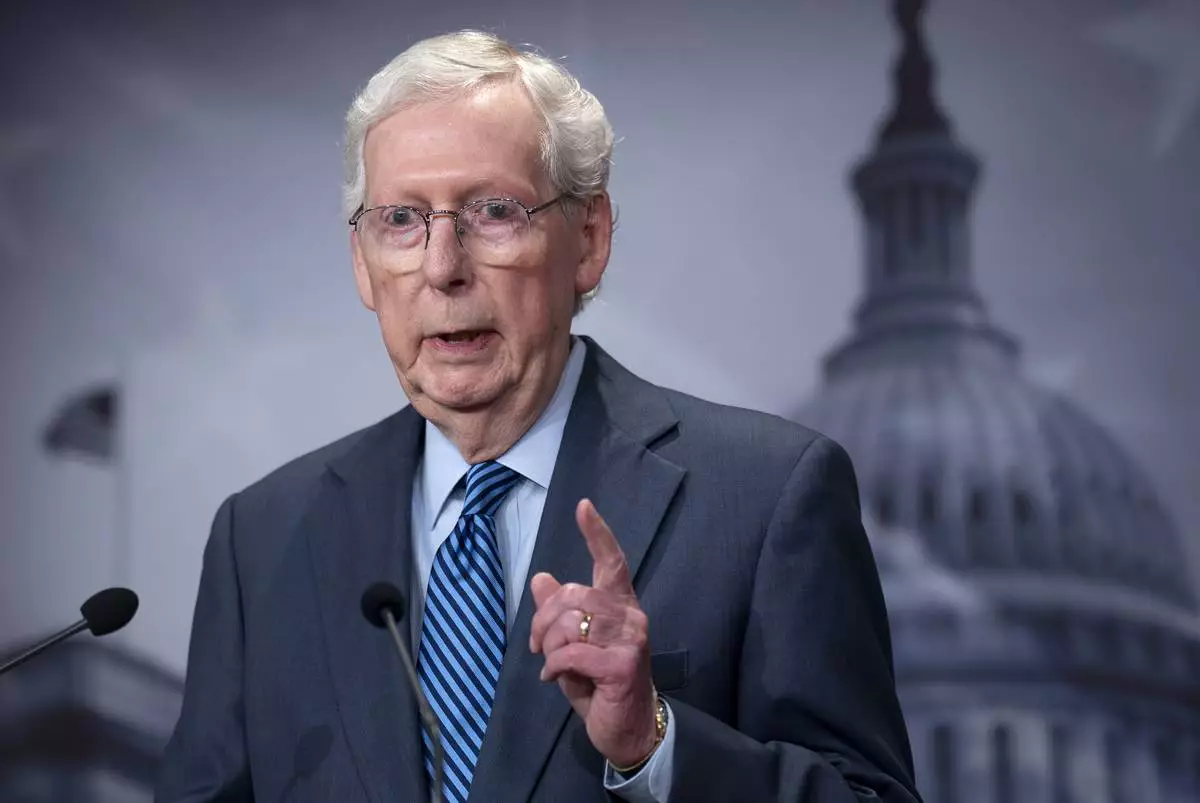

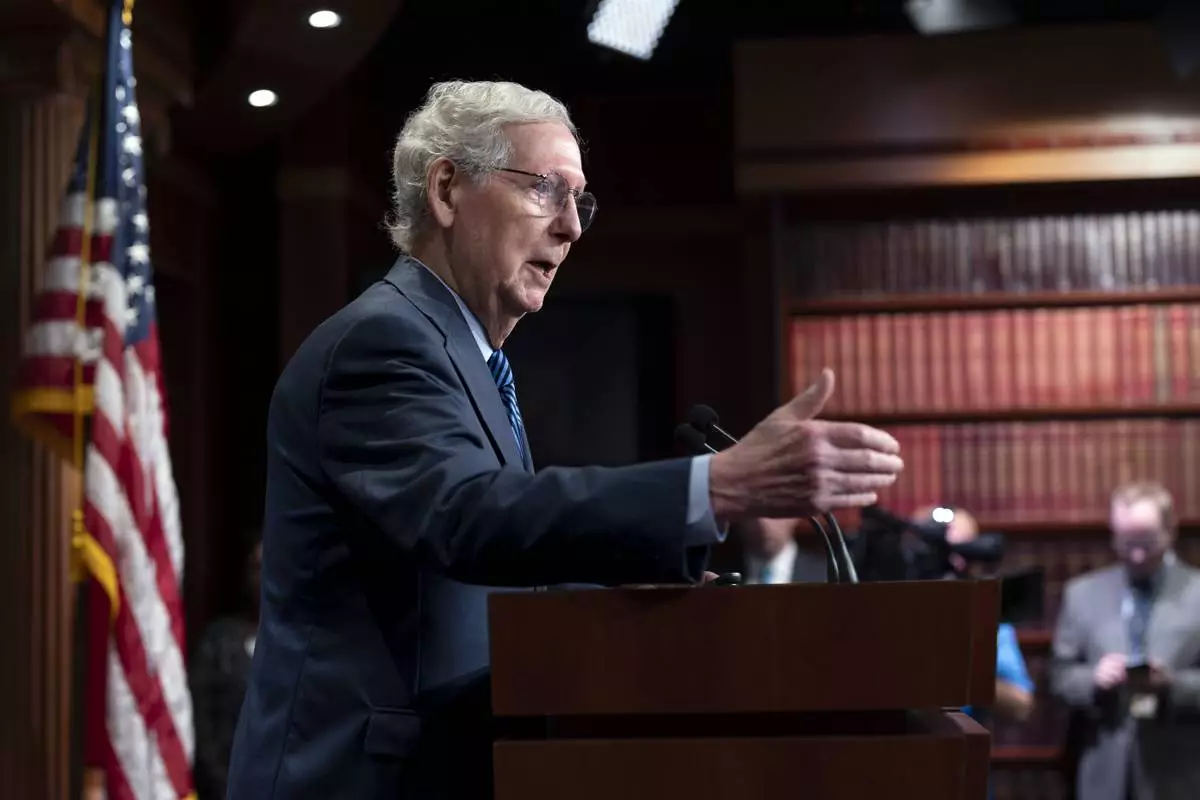

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., praises support for Ukraine as the Senate is on track to pass $95 billion in war aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., praises support for Ukraine as the Senate is on track to pass $95 billion in war aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

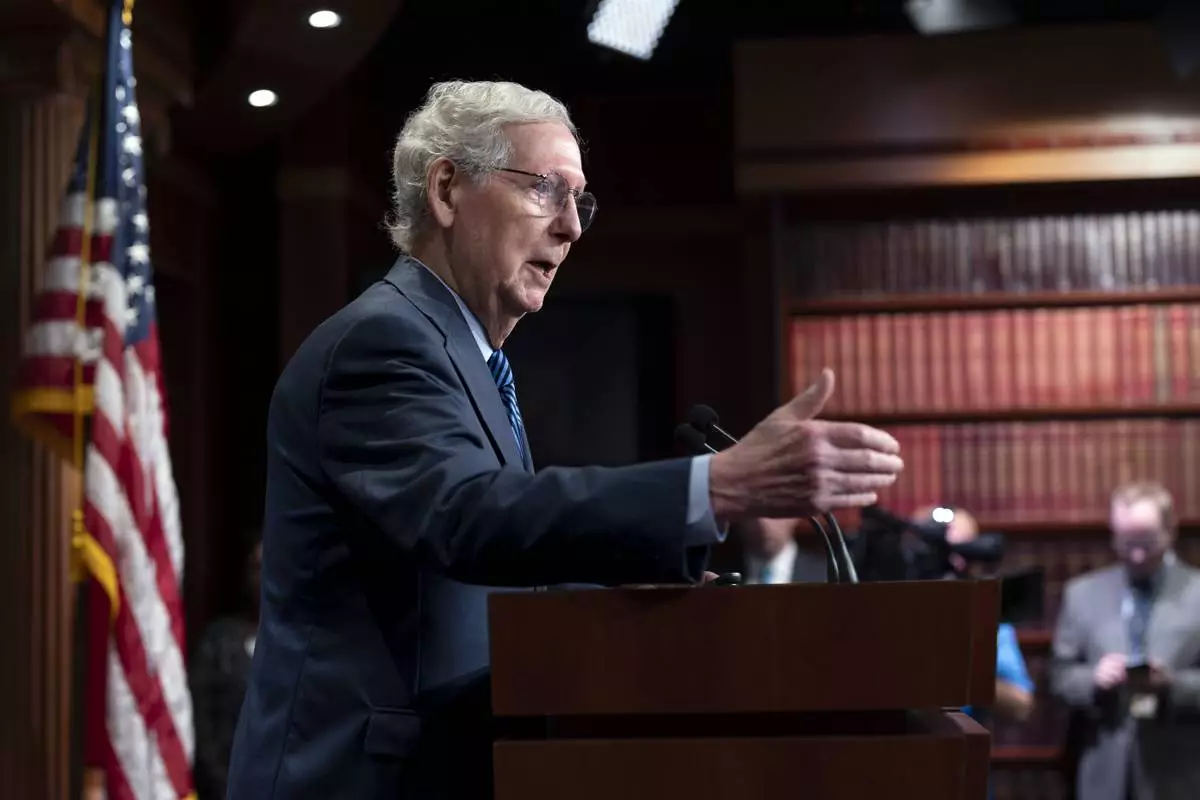

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., walks to the chamber as the Senate prepares to advance the $95 billion aid package for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan passed by the House, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)