Keen for others to learn from her tragedy, Sarah Brookes is now calling for sunbeds to be banned.

A mum-of-two who had a course of sunbeds as a “one-off” to avoid being a “pasty-faced bridesmaid” has revealed how she now has stage four advanced skin cancer.

Always vigilant about sun safety, Sarah Brookes, 41, of Bradford, West Yorkshire, said when she watched her boys, Morgan, 15, and Mason, 12, out playing, she would slather them with sun cream.

But when the progress support leader – similar to a supply teacher – and mentor for young carers was asked to be a bridesmaid for a friend she does not wish to name, and the bride suggested everyone should have a course of sunbeds to give them a golden glow in the photos of her big day, she agreed.

Married to Autoglass worker Darren, 43, Sarah, who is now campaigning alongside charity Melanoma UK to ban the commercial use of sunbeds, said: “I’d actually always been happy with my pale skin, but I agreed as I didn’t want to upset the bride, who didn’t want pasty-faced bridesmaids.

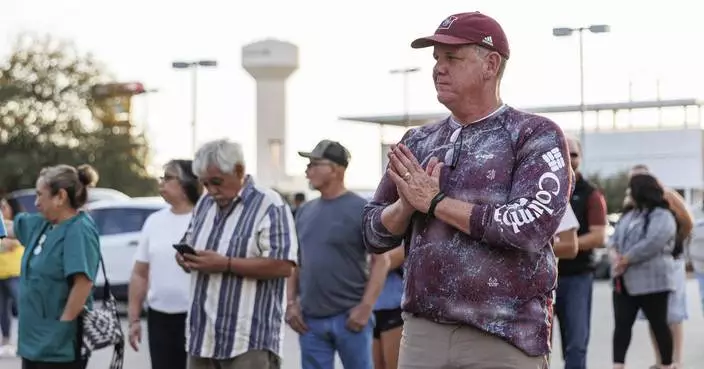

Sarah as a bridesmaid (PA Real Life/Collect)

“I know I could have refused, but it was about five or six years ago and back then, I’d no idea just how dangerous sunbeds could be. Plus because of a number of allergies to different chemicals I have I didn’t want to have a spray tan in case I flared up.

“I’ve never been a sun worshipper – my parents used to jokingly call me a vampire. Doctors cannot say what caused this, but in my mind, if I hadn’t gone on those sunbeds, I wouldn’t be in this position now.”

Following her 10 three-minute sessions, Sarah forgot all about her sunbed treatments until one day in 2016 when, out-of-the-blue, she was driving along with Morgan when he noticed that the back of her ear was bleeding.

The spot behind Sarah's ear (PA Real Life/Collect)

“His exact words were, ‘Mum, that’s minging,’” she said. “We drove straight to the pharmacy, where they said I had an infected spot.

“I was told to keep an eye on it and go straight to the doctor if it got hot. But it didn’t, so I forgot all about it.”

After that Sarah forgot about the spot again until later that year, when her mum Susan Burness, 68, pointed it out.

This time, however, when she consulted her doctor, she was urgently referred to a dermatologist at St Luke’s Hospital in Bradford.

Sarah during radiotherapy (PA Real Life/Collect)

At the start of September 2016, when she went in for her appointment, she was wheeled straight down to theatre to have a mass behind her ear removed and sent off for testing.

Two weeks later, the results revealed that, tragically, she had stage three malignant melanoma – a type of skin cancer.

“I just remember sitting there reeling, waiting for a cancer nurse to come and tell me what would happen next,” she said. “They told me they’d need to remove part of my ear to check the cancer margins.

Sarah after her neck surgery (PA Real Life/Collect)

“Bizarrely, I remember wondering if I’d still be able to wear earrings. It’s funny the things you think. But I knew that, no matter how it looked afterwards, I had to go ahead with the operation. It was either save my ear or save my life.”

Three weeks later, in October 2016, Sarah went under the knife, also having reconstructive surgery.

She continued: “It almost looks like a jigsaw. They stitched it all together, so it’s ear shaped, but just a lot smaller. I call it my mini ear.”

During the operation, doctors – who are unable to confirm what has caused her cancer – also injected Sarah with a radioactive dye, designed to highlight any further cancer traces evident in her body.

Sarah and Morgan (PA Real Life/Collect)

Worryingly, they revealed the disease had spread to some lymph nodes in her neck.

Once they were removed and sent away for testing, though, a CT scan seemed to show she was in the clear.

“I was practically dancing after that,” recalled Sarah. “I thought that was it. It was over.”

But, around eight weeks later, in December 2016, the lymph node results came back, showing they contained malignant cancer cells.

So, in January 2017, Sarah had an operation known as a neck dissection, where doctors make an incision from the chin to the neck, then up towards the ear.

She continued: “That was absolutely horrendous. I looked like Frankenstein’s monster, all swollen up and covered in stitches.”

“My boys couldn’t even look at me. I’d been unsure about whether to let them see me like that, but they insisted they’d seen worse on YouTube. In fact, I trumped YouTube,” she continued.

“Seeing my own family, unable to look me in the eye, made it all real. Everyone just sat there trying not to cry.

“I wish I’d never had those sunbeds. I believe they are the reason for all of this. Doctors have asked if I ever burnt my ears as a child, but I don’t recall that happening, and neither does my mum.”

Post-surgery, something in Sarah – who believes it is important to be open, but positive, with her children about her battle – flipped and she became determined to educate others on sun safety, using her scar as an educational tool.

Still working in a school at the time, she spoke to children – especially young girls – about her experience.

Sarah and her family (PA Real Life/Collect)

“There’s a lot of pressure on young girls around looks, and for them to look a certain way,” she explained. “The media portray a tan as healthy, when in reality, it’s damaged skin. Whenever it was sunny, I’d make sure to remind people about using lotion and staying in the shade.”

Still juggling treatment with her tireless crusade to educate others, Sarah began an intensive course of radiotherapy in March 2017.

She added: “Nothing I’d been through so far was as bad as that. It was like having sun stroke that got a little worse every day.

“My mouth blistered, and all my taste buds burnt off. My throat blistered too, but I’d also be sick which felt agonising.”

She continued: “The exhaustion was something else. I thought, being a mum, I knew what being tired felt like – but this was like my entire body, apart from my mind, was asleep. I can’t tell you how relieved I was to ring that bell on the ward to mark my treatment being over.”

By August 2017, Sarah started to feel back to herself again, and was looking forward to rebuilding her life. But then, she was suddenly struck by “lightning bolt” headaches.

At first, she was told it was probably an ear infection, caused by the radiotherapy drying and damaging her skin but, unconvinced, she asked her cancer nurse to arrange some scans.

Tragically, at the end of November, an MRI scan detected a tumour in her brain – meaning her cancer was now stage four.

“After that news, I had to give up my driving license in case the tumour caused any seizures,” she said. “I found that loss of independence incredibly hard.

“I’ve been driving since I was 18 and all of a sudden I was robbed of all those little things, like being able to pick the kids up, or nip out to the shops. Now, I have to plan every single outing with so much precision.”

Meeting with a specialist, Sarah decided to go for gamma knife surgery – a pioneering radiation treatment, which uses a focused array of beams to treat brain lesions.

By the time the operation rolled round on 14 December 2017 though, the original tumour had trebled in size, and two more had sprung up.

Still, the procedure appeared to be a success, and doctors were confident they had removed all traces of the tumours.

Two months later, though, the “lightning bolt” headaches returned, and a scan revealed two new tumours had grown.

“That was hard to hear, but I was offered the gamma knife surgery again, and it’d been successful last time, so I thought, ‘At least it’s treatable,’” said Sarah.

“I was put on steroids to help me prepare for the surgery, but I had quite a bad reaction to them. I was so exhausted I could barely walk. I gained around 1.5st in two weeks with it all.”

During her recovery after the second bout of gamma knife surgery, Sarah reached out to the charity Melanoma UK, having previously discovered them through a Facebook support group.

Since then, they have been an invaluable source of emotional, practical and financial support to her in her hour of need.

“They’ve been a lifeline. They helped with things I hadn’t even considered before now,” she said. “Through one of their grants, I was able to get a scooter, which now makes it far easier for me to get around.”

Tragically, Sarah’s fight is far from over as, in April 2018 – the week before she was due to have a second session of immunotherapy – she discovered the cancer had spread to the lining of her brain, meaning her condition is now classed as advanced.

But, despite this, she is determined to stay positive, especially as her body is responding well to the chemotherapy she is currently having.

“My motto is cry tonight, fight tomorrow. And that’s what I’ll do,” she said.

Determined that her suffering won’t be in vain, Sarah has dedicated her time to working with Melanoma UK, backing their campaign to ban the commercial use of sunbeds in the UK.

With skin cancer rates soaring – as shown in a 2015 study by Cancer Research UK, which reported 15,906 new cases, and noted that 86 per cent were preventable – their message is more vital than ever.

A similar ban to the one being proposed was rolled out in Australia in 2013 in a bid to slash the skin cancer death rate there.

Sarah explained: “With the campaign, we aren’t trying to put people out of jobs – we’ll work with them to retrain them in spray tanning. But we don’t want people to die either.

“The amount of unregulated sunbed use is shocking. People can go on for as long as they like, with no warnings displayed. You see warnings on cigarette packets, on alcohol, even before gambling adverts – why aren’t there any in tanning salons?

“It’s hard knowing this disease can be preventable. Avoiding a sunbed can literally save your life. I don’t want anyone else going through this. I’m only 41, and here I am, praying I’ll see my kids grow up.”

She added: “Cancer doesn’t just affect the person is happening to. This has changed the lives of everyone I love. I’m the atom bomb in the centre of it all – but they’re all caught in the explosion.”

Dr Christian Aldridge, Consultant Dermatologist said: “It has been well established previously that natural ultraviolet radiation (UVR) can cause skin cancer. There is now a large body of robust scientific evidence that clearly demonstrates that sunbeds increase your risk of melanoma.

“These findings are also backed up by IARC, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, who state that sunbeds provide no positive health benefits. The risks are greater for younger people as using sunbeds for the first time before the age of 35 increases your risk of melanoma by 60 per cent”

To sign the petition, visit petition.parliament.uk/petitions/223903 and to read more information about melanoma visit www.melanomauk.org.uk