Daniel. Rachel. Isaiah.

"You can't prove a negative," our teachers and parents sometimes tell us when we're young.

Yet when I look back upon my time in Colorado covering the almost-adults who were killed in the Columbine High School attack 20 years ago this week, all I can see are the negatives: the people who aren't there anymore. I think of their names — names I typed and said and thought of, over and over, for a time.

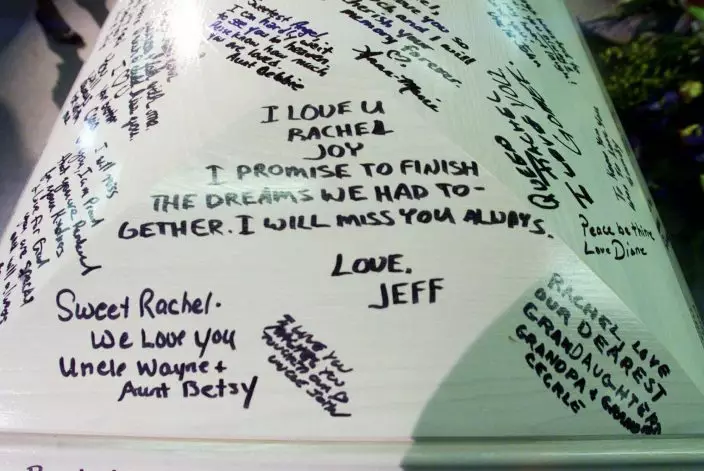

FILE - In this April 24, 1999, file photo, the casket bearing Columbine High School shooting victim Rachel Joy Scott is signed with notes of remembrance from family members as it sits at the Trinity Christian Center in Littleton, Colo. Twelve students and one teacher were killed in a murderous rampage at the school on April 20, 1999, by two students who killed themselves in the aftermath. (AP PhotoRick Wilking, Pool, File)

Corey. Kyle. Kelly.

Nearly half my life later, when I think of Columbine, it isn't what actually happened that occupies my mind. Instead, my brain goes to what's no longer there. It goes to the undefined, usually unnoticed holes in the fabric of today — the spaces where people I never met are missing from the world for longer than they were here. To the long, silent aftermaths where lives used to be. To the names that fleetingly became part of my moment-to-moment life and then, as for so many, receded and faded.

Cassie. Steve. Daniel again.

FILE - In this April 21, 1999, file photo, from left, Rachel Ruth, Rhianna Cheek and Mandi Annibel, all 16-year-old sophomores at Heritage High School in Littleton, Colo., console each other during a vigil service to honor the victims of the shooting spree in Columbine High School in the southwest Denver suburb of Littleton, Colo. Twelve students and one teacher were killed in a murderous rampage at the school on April 20, 1999, by two students who killed themselves in the aftermath. (AP PhotoLaura Rauch, File)

So often now, Americans find themselves confronting days in which shots are fired, children fall and futures are stolen. In moments of gunfire, worlds of possibilities are wiped away. Millions of things that would have happened melt into nothingness.

John. Matt. Lauren. Coach Dave.

Covering Columbine, I witnessed that feeling of unthinkable school-day chaos up close for the first time. Looking back, I realize now: It was, really, a preview for an entire era of tears yet to be shed, of unwelcome gaps yet to be created. Of negatives yet to be proven.

I've chronicled tragedy for all of my adult life, from rural Pennsylvania to urban China, from Afghanistan to Iraq. During my first job as a police reporter right after college, after I returned from a particularly harrowing murder scene, one of my mentors said to me: "You'll get used to it." That turned out to be wrong.

It was never the details of tragedies that lingered with me. It was the quiet aftermaths, the times when families and friends began to let in that a life had ended, that a future so many loved ones had counted on was no longer potential but had become, purely and simply, fiction.

Would one of them have discovered a cure for cancer? Become an NBA star? Traveled the world and learned from its people? Raised a family, been part of a community, paid a mortgage, shopped for groceries on the weekend, coached a youth sports team?

Made the world better, smarter, kinder?

These days, one of the things I sometimes do at work is called a "gap analysis." It's corporate jargon for an exercise in identifying the places in a business where things are lacking, or needed, and it's the first step toward figuring out how to make them whole.

Twenty years later, I still find myself doing a mental gap analysis of Columbine, though nothing can ever make anything whole. What I always come back to, which makes me dizzy, is contemplating what the world is lacking because these 12 young people and this teacher were abruptly removed from humanity's equation one April morning as the last millennium's final days waned. All because of two young men who decided that violence would be their final path forward.

I'd like to say that I understand things a bit better now. I've written hundreds of stories since then about all corners of the world. I've seen parts of the planet I never thought I'd see. And now I have kids in schools that do emergency drills as a matter of routine. It is the background hum of a world that, to them, has always been this way.

I'd like to say those things have helped me make sense of Columbine when I look at it over my shoulder from two decades on. I'd like to say that, but I'd be lying to you. I'm still trying, though. Not as a journalist, necessarily, but as an American.

In daily journalism, the job is often to cover what has just happened, and it is frequently very loud. But more than you'd think, the quieter stories — the more important stories, even — are the ones that didn't happen. Those are the more complex ones, too. And in the cacophony, they're harder and harder to find.

But my profession is, at its heart, a quest not only for fact but for context. And that may be where we can actually help.

What we can do is look back on the traumatic things we've covered, revisit them, study them to hone and sharpen what we do. We can understand that even as we show the world the facts and the stories behind them, we also can create unintended consequences by amplifying people and actions that can be held up by ailing minds as accomplishments to be replicated. And we can use this information to do it all better the next time.

Coach Dave. Lauren. Matt. John.

"You can't prove a negative," they say. Maybe not. But you can notice one, and keep noticing it.

Daniel. Steve. Cassie.

You can remember, as a journalist, the people from the stories you covered who are no longer here. You can wonder about their lives, and the people they left behind, and the ruthlessness of continuity that allows the world to fill in the gaps they left and move on to other spectacles, other triumphs, other tragedies and losses.

Kelly. Kyle. Corey.

And now and then, on a milestone anniversary that is no cause for celebration, you can sit in a quiet room and say, out loud, the names of people you never knew and hear them echo in a world that no longer contains them.

Isaiah. Rachel. Daniel. Again.

Ted Anthony, director of digital innovation for The Associated Press, covered the Columbine High School shootings and their aftermath in 1999. Follow him on Twitter at @anthonyted