The 3-year-old girl traveled for weeks in her father's arms, as he set out to seek asylum in the United States. Now she won't even look at him.

After being forcibly separated at the border by government officials, sexually abused in U.S. foster care and deported, she arrived back in Honduras convinced her once-beloved father abandoned her. He fears their bond is forever broken.

Click to Gallery

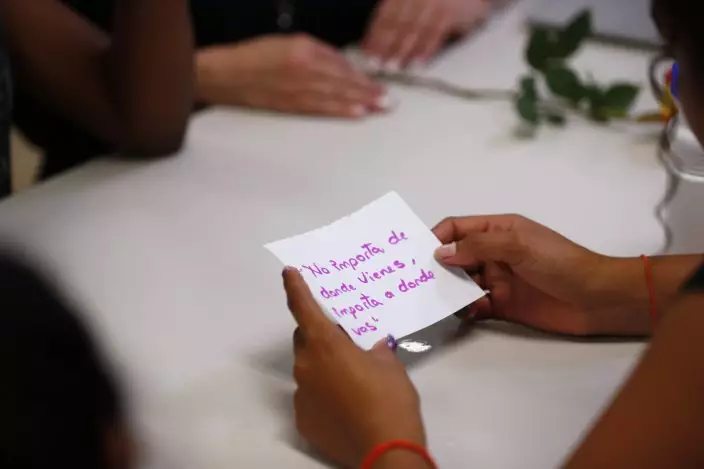

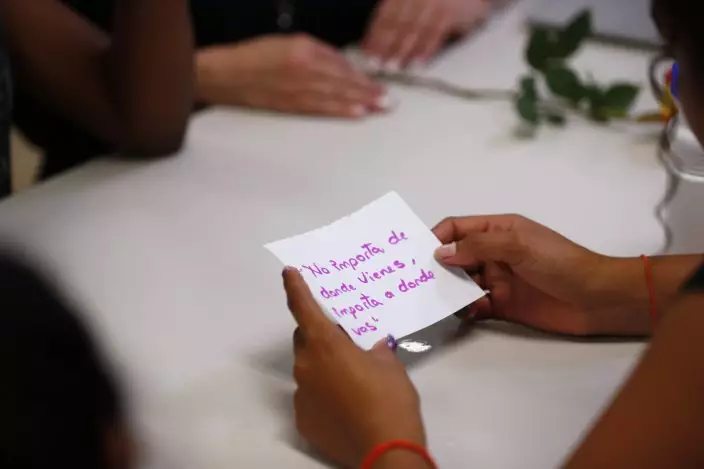

In this Sept. 24, 2019, photo, a migrant girl in U.S. government custody holds a card that says, in Spanish, “It doesn’t matter where you come from, it matters where you are going,” during a lesson on reproductive health and self esteem in Lake Worth, Fla. Detention can be traumatic for children, and the nonprofit U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants opened the federally funded Rinconcito del Sol shelter this summer, aiming to make it a model of excellence. Rinconcito del Sol is one of 170 detention centers, residential shelters and foster programs in 23 states which held nearly 70,000 migrant kids in the past year. (AP PhotoWilfredo Lee)

The 3-year-old girl traveled for weeks in her father's arms, as he set out to seek asylum in the United States. Now she won't even look at him.

This month new government data shows the little girl is one of an unprecedented 69,550 migrant children held in U.S. government custody over the past year, enough infants, toddlers, kids and teens to overflow the typical NFL stadium.

In this Sept. 24, 2019, photo, girls play dominos with a staff member at a shelter for migrant teenage girls, in Lake Worth, Fla. The nonprofit U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants opened the federally funded Rinconcito del Sol shelter this summer, aiming to make it a model of excellence in a system of 170 detention centers, residential shelters and foster programs which held nearly 70,000 migrant kids in the past year. (AP PhotoWilfredo Lee)

In this Sept. 24, 2019, photo, a migrant girl in U.S. government custody holds a card that says, in Spanish, “It doesn’t matter where you come from, it matters where you are going,” during a lesson on reproductive health and self esteem in Lake Worth, Fla. Detention can be traumatic for children, and the nonprofit U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants opened the federally funded Rinconcito del Sol shelter this summer, aiming to make it a model of excellence. Rinconcito del Sol is one of 170 detention centers, residential shelters and foster programs in 23 states which held nearly 70,000 migrant kids in the past year. (AP PhotoWilfredo Lee)

This Aug. 23, 2019, photo shows a stuffed animal hanging to dry at the Comayagua, Honduran home of a 3-year-old who was separated from her father when they tried to seek asylum at the U.S. southern border. She was sexually abused in U.S. foster care, according to court records. She was later deported and arrived back in Honduras withdrawn, anxious and angry. (AP PhotoElmer Martinez)

In this Aug. 23, 2019, photo, a Honduran father talks during an interview in Comayagua, Honduras about being separated from his 3-year-old daughter at the border after traveling for weeks to seek asylum in the U.S. Now she won’t even look at him. (AP PhotoElmer Martinez)

In this Aug. 23, 2019, photo, a Honduran father stands at his home in Comayagua, Honduras, after talking in an interview about being separated from his 3-year-old daughter at the border after traveling for weeks to seek asylum in the U.S. According to court records, his daughter was sexually abused in U.S. foster care. She was later deported and arrived back in Honduras withdrawn, anxious and angry. He fears their bond is forever broken. (AP PhotoElmer Martinez)

"I think about this trauma staying with her too, because the trauma has remained with me and still hasn't faded," he said, days after their reunion.

FILE - In this Sept. 24, 2019, file photo, girls dance as they do exercises at a shelter for migrant teenage girls, in Lake Worth, Fla. The nonprofit U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants opened the federally funded Rinconcito del Sol shelter this summer, aiming to make it a model of excellence in a system of 170 detention centers, residential shelters and foster programs which held nearly 70,000 migrant kids in the past year. (AP PhotoWilfredo Lee, File)

This month new government data shows the little girl is one of an unprecedented 69,550 migrant children held in U.S. government custody over the past year, enough infants, toddlers, kids and teens to overflow the typical NFL stadium.

In this Sept. 24, 2019 photo, girls eat lunch at a shelter for migrant teenage girls, in Lake Worth, Fla. The nonprofit U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants opened the federally funded Rinconcito del Sol shelter this summer, aiming to make it a model of excellence in a system of 170 detention centers, residential shelters and foster programs which held nearly 70,000 migrant kids in the past year. (AP PhotoWilfredo Lee)

In this Sept. 24, 2019, photo, girls play dominos with a staff member at a shelter for migrant teenage girls, in Lake Worth, Fla. The nonprofit U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants opened the federally funded Rinconcito del Sol shelter this summer, aiming to make it a model of excellence in a system of 170 detention centers, residential shelters and foster programs which held nearly 70,000 migrant kids in the past year. (AP PhotoWilfredo Lee)

In this Sept. 24, 2019, photo, a migrant girl in U.S. government custody holds a card that says, in Spanish, “It doesn’t matter where you come from, it matters where you are going,” during a lesson on reproductive health and self esteem in Lake Worth, Fla. Detention can be traumatic for children, and the nonprofit U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants opened the federally funded Rinconcito del Sol shelter this summer, aiming to make it a model of excellence. Rinconcito del Sol is one of 170 detention centers, residential shelters and foster programs in 23 states which held nearly 70,000 migrant kids in the past year. (AP PhotoWilfredo Lee)

This Aug. 23, 2019, photo shows a stuffed animal hanging to dry at the Comayagua, Honduran home of a 3-year-old who was separated from her father when they tried to seek asylum at the U.S. southern border. She was sexually abused in U.S. foster care, according to court records. She was later deported and arrived back in Honduras withdrawn, anxious and angry. (AP PhotoElmer Martinez)

In this Aug. 23, 2019, photo, a Honduran father talks during an interview in Comayagua, Honduras about being separated from his 3-year-old daughter at the border after traveling for weeks to seek asylum in the U.S. Now she won’t even look at him. (AP PhotoElmer Martinez)

In this Aug. 23, 2019, photo, a Honduran father stands at his home in Comayagua, Honduras, after talking in an interview about being separated from his 3-year-old daughter at the border after traveling for weeks to seek asylum in the U.S. According to court records, his daughter was sexually abused in U.S. foster care. She was later deported and arrived back in Honduras withdrawn, anxious and angry. He fears their bond is forever broken. (AP PhotoElmer Martinez)

WASHINGTON (AP) — U.S. intelligence officials have determined that Russian President Vladimir Putin likely didn’t order the death of imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny in February, according to an official familiar with the determination.

While U.S. officials believe Putin was ultimately responsible for the death of Navalny, who endured brutal conditions during his confinement, the intelligence community has found “no smoking gun” that Putin was aware of the timing of Navalny's death — which came soon before the Russian president's reelection — or directly ordered it, according to the official.

The official spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the sensitive matter.

Soon after Navalny’s death, U.S. President Joe Biden said Putin was ultimately responsible but did not accuse the Russian president of directly ordering it.

At the time, Biden said the U.S. did not know exactly what had happened to Navalny but that “there is no doubt” that his death “was the consequence of something that Putin and his thugs did.”

Navalny, 47, Russia’s best-known opposition politician and Putin’s most persistent foe, died Feb. 16 in a remote penal colony above the Arctic Circle while serving a 19-year sentence on extremism charges that he rejected as politically motivated.

He had been behind bars since January 2021 after returning to Russia from Germany, where he had been recovering from nerve-agent poisoning that he blamed on the Kremlin.

Russian officials have said only that Navalny died of natural causes and have vehemently denied involvement both in the poisoning and in his death.

In March, a month after Navalny’s death, Putin won a landslide reelection for a fifth term, an outcome that was never in doubt.

The Wall Street Journal first reported about the U.S. intelligence determination.

FILE - Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny gestures while speaking during his interview to the Associated Press in Moscow, Russia on Dec. 18, 2017. U.S. intelligence officials have determined that Russian President Vladimir Putin likely didn't order the death of Navalny, the imprisoned opposition leader, in February of 2024. An official says the U.S. intelligence community has found "no smoking gun" that Putin was aware of the timing of Navalny's death or directly ordered it. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko, File)