Weston McKennie thought back to when he first met Christian Pulisic, a pair of 13-year-olds on a bus from a hotel to training camp in Carson, California.

“I used to sit behind him. I used to squirt empty air with a little bit of water into his ear,” McKennie said. “I was scared to take the elevator, so he used to walk with me up the stairs, like 11 flights of stairs, after training all the time.”

A dozen years later, they are mainstays on the U.S. national team as it prepares for this summer's Copa América and the 2026 World Cup, but first will be rivals when Pulisic's AC Milan faces McKennie's Juventus on April 27 or 28 with second place at stake in Italy's Serie A.

“More fun playing with him, so I don’t really have to worry about him offensively,” McKennie said with a laugh during a conference call Tuesday to promote the match.

Both found success as teenaged American standouts in Europe, struggled in their early 20s and reemerged in 2023-24 for their best club seasons as 25-year-olds.

Pulisic has thrived under coach Stefano Pioli, scoring 10 Serie A goals and 13 overall, topping his previous highs of nine league goals and 11 overall with Chelsea in 2019. He was given a string of starts on the right side of the attack — U.S. coach Gregg Berhalter has preferred him on the left — and of late has been shifted to a central attacking midfield role.

Pulisic regained what he termed “that self belief.”

“I don’t think it’s so important to exactly find the exact reason for why I’ve scored some more goals or whatever you want to call success,” he said. “It comes and goes at times in players' careers and we both kind of needed to find that again and, yeah, luckily we have.”

A native of Hershey, Pennsylvania, Pulisic debuted with Borussia Dortmund at age 17 in January 2016 and moved to Chelsea for the 2019-20 season. He became the first American to play in a Champions League final in 2021, winning a medal, but struggled for playing time in 2022-23 under his third manager in four seasons. In his 2022 book, Pulisic disclosed he battled depression in the winter of 2020-21.

While Pulisic is expressive and introspective, McKennie is the U.S. national team extrovert.

“I might be a little bit different than Christian in terms of I want to be happy,” he said. “I want to feel like I’m at home because being away from family a lot, it’s very important for me to have a kind of family environment and people that I get along with.”

McKennie spoke of the upcoming matchup as a competition for “bragging rights,” and Pulisic of how when they get together it becomes time for video games.

McKennie said he missed ranch dressing and Cheez-Its in Italy and smirked while saying the crackers should be kept away from Pulisic.

“You can’t give the Cheez-Its to Christian. He'll kill 'em," McKennie said.

“That's such a lie,” shot back Pulisic, cracking up.

Citing the switch to Serie A as ideal, McKennie mentioned Pulisic even gets to live on a golf course. Pulisic cited "the change in mindset and just the way of life here, feeling that family environment” and his face brightened when he discussed “the trust and the confidence from a top team, and being given that right away.”

McKennie was born in Fort Lewis, Washington, spent a good deal of his youth in Little Elm, Texas, then left the FC Dallas academy and made his pro debut at age 18 with Germany’s Schalke in May 2017. He was loaned to Juventus for the 2020-21 season and signed a four-year contract in March 2021. He struggled at times and was loaned to relegation-bound Leeds for the second half of the 2022-23 Premier League season, then returned to Juventus and became a standout this season under coach Massimiliano Allegri. McKennie leads the team with seven assists in 30 Serie A matches.

“During the summer, I looked at myself and realized I lost a little bit belief in myself, to be completely honest. The confidence was kind of low.,” McKennie said.

McKennie recalled a conversation with Allegri when preseason training began last summer.

“He joked with me a little bit, was like Wes, you got to start running now and you stop running at the end of the season,” McKennie said. “So that’s kind of what I’ve been doing.”

Running is fine. Tight indoor spaces are not.

McKennie still hasn't gotten over his elevator phobia.

“I still jump out the elevator when too many people get in,” he said. “I get caught waiting the whole time.”

Both spoke of the pride for playing for the U.S., which as the second-youngest team in the tournament reached the second round in Qatar two years ago before getting knocked out by the Netherlands.

“With the showing that we had in 2022, I think we kind of open the eyes up to the world that we can compete and we’re not just looked at as a team that goes until the final whistle," McKennie said. "We have that quality, but now we can also play, as well.”

He anticipated chippier play at the Copa América, where the U.S. opens against Bolivia on June 23, plays Panama four days later and finishes the group stage against Uruguay on July 1.

“This summer will be an amazing test again and where we can show the CONCACAF side of us a little bit," McKennie said, laughing, "the little more I guess you can say dirty side — I don’t really want to say that.”

FILE - United States' Weston Mckennie, left, and Christian Pulisic celebrate after Mckennie's goal during the first half of a CONCACAF Gold Cup soccer match against Curacao, Sunday, June 30, 2019, in Philadelphia. The United States won 1-0. Having revived their careers in Italy, AC Milan's Christian Pulisic and Juventus' Weston McKennie are looking forward to facing each other later this month in Serie A before joining the U.S. national team for the Copa América. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum, File)

FILE - United States' Weston McKennie celebrates his goal with Tyler Adams, left, and Christian Pulisic during the second half of a FIFA World Cup qualifying soccer match against Mexico, Friday, Nov. 12, 2021, in Cincinnati. The U.S. won 2-0. Having revived their careers in Italy, AC Milan's Christian Pulisic and Juventus' Weston McKennie are looking forward to facing each other later this month in Serie A before joining the U.S. national team for the Copa América. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez, File)

MADISON, Wis. (AP) — It was the music that changed first. Or maybe that’s just when many people at the pale brick Catholic church in the quiet Wisconsin neighborhood finally began to realize what was happening.

The choir director, a fixture at St. Maria Goretti for nearly 40 years, was suddenly gone. Contemporary hymns were replaced by music rooted in medieval Europe.

So much was changing. Sermons were focusing more on sin and confession. Priests were rarely seen without cassocks. Altar girls, for a time, were banned.

At the parish elementary school, students began hearing about abortion and hell.

“It was like a step back in time,” said one former parishioner, still so dazed by the tumultuous changes that began in 2021 with a new pastor that he only spoke on condition of anonymity.

It’s not just St. Maria Goretti.

Across the U.S., the Catholic Church is undergoing an immense shift. Generations of Catholics who embraced the modernizing tide sparked in the 1960s by Vatican II are increasingly giving way to religious conservatives who believe the church has been twisted by change, with the promise of eternal salvation replaced by guitar Masses, parish food pantries and casual indifference to church doctrine.

The shift, molded by plummeting church attendance, increasingly traditional priests and growing numbers of young Catholics searching for more orthodoxy, has reshaped parishes across the country, leaving them sometimes at odds with Pope Francis and much of the Catholic world.

The changes are not happening everywhere. There are still plenty of liberal parishes, plenty that see themselves as middle-of-the-road. Despite their growing influence, conservative Catholics remain a minority.

Yet the changes they have brought are impossible to miss.

The progressive priests who dominated the U.S. church in the years after Vatican II are now in their 70s and 80s. Many are retired. Some are dead. Younger priests, surveys show, are far more conservative.

“They say they’re trying to restore what us old guys ruined,” said the Rev. John Forliti, 87, a retired Twin Cities priest who fought for civil rights and reforms in Catholic school sex education.

Doug Koesel, an outspoken 72-year-old priest at Blessed Trinity Parish in Cleveland, was blunter: “They’re just waiting for us to die.”

At St. Maria Goretti, once steeped in the ethos of Vatican II, many parishioners saw the changes as a requiem.

“I don’t want my daughter to be Catholic,” said Christine Hammond, whose family left the parish when the new outlook spilled into the church’s school and her daughter’s classroom. “Not if this is the Roman Catholic Church that is coming.”

But this is not a simple story. Because there are many who welcome this new, old church.

They often stand out in the pews, with the men in ties and the women sometimes with the lace head coverings that all but disappeared from American churches more than 50 years ago. Often, at least a couple families will arrive with four, five or even more children, signaling their adherence to the church’s ban on contraception, which most American Catholics have long casually ignored.

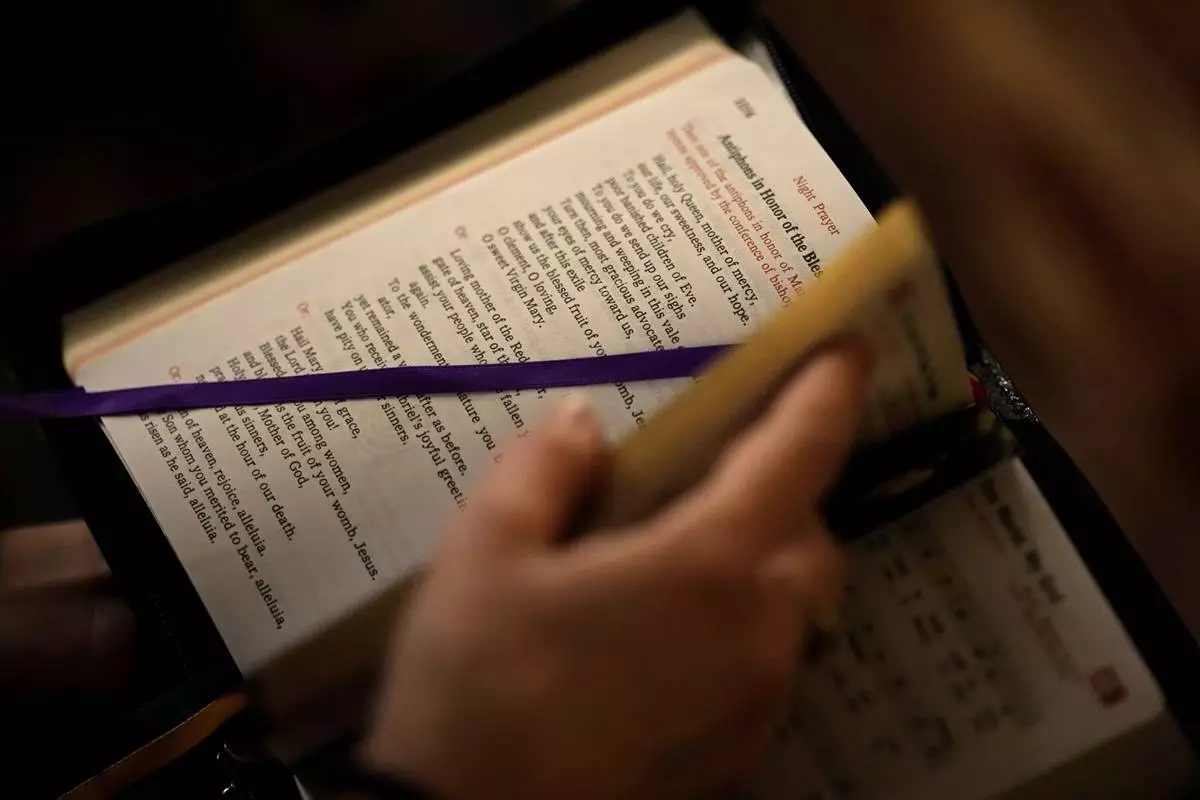

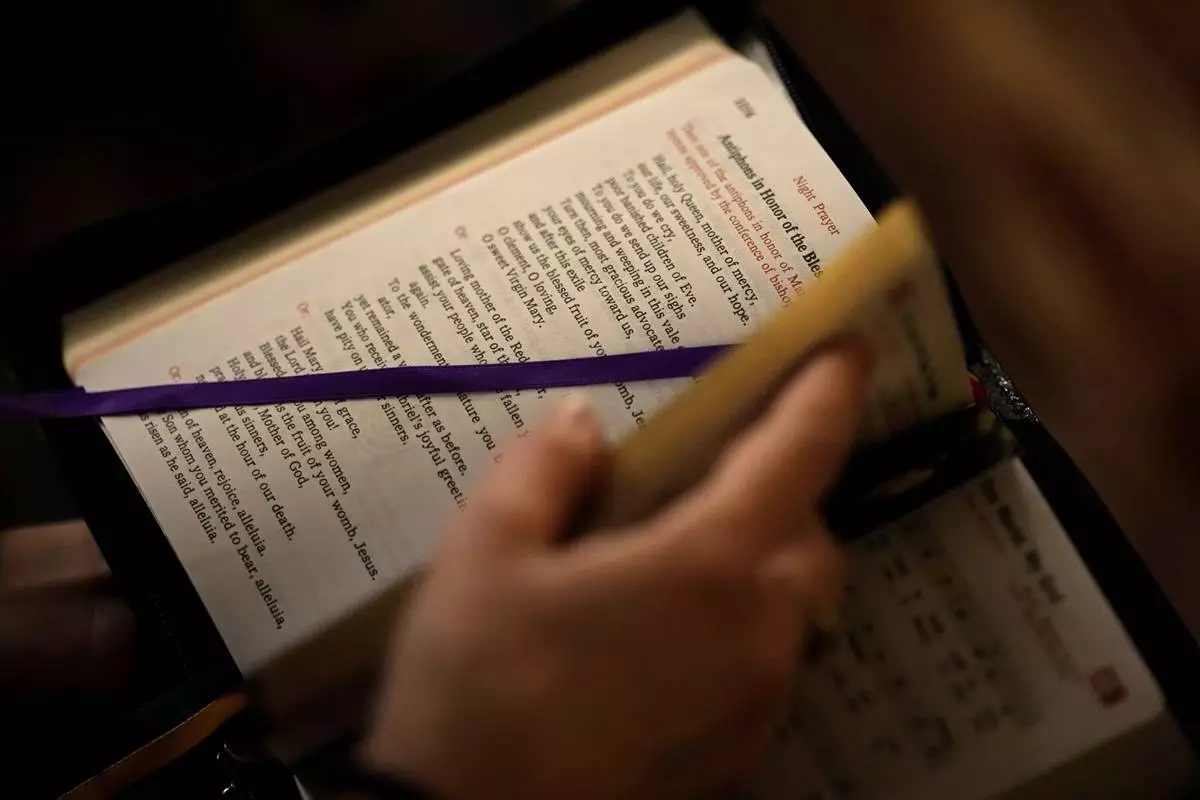

They attend confession regularly and adhere strictly to church teachings. Many yearn for Masses that echo with medieval traditions – more Latin, more incense more Gregorian chants.

“We want this ethereal experience that is different from everything else in our lives,” said Ben Rouleau, who until recently led St. Maria Goretti’s young adult group, which saw membership skyrocket even as the parish shrank amid the turmoil.

They are, Rouleau said, happily out of touch with a liberal city like Madison.

“It’s radical in some ways,” Rouleau said. “We’re returning to the roots of the church.”

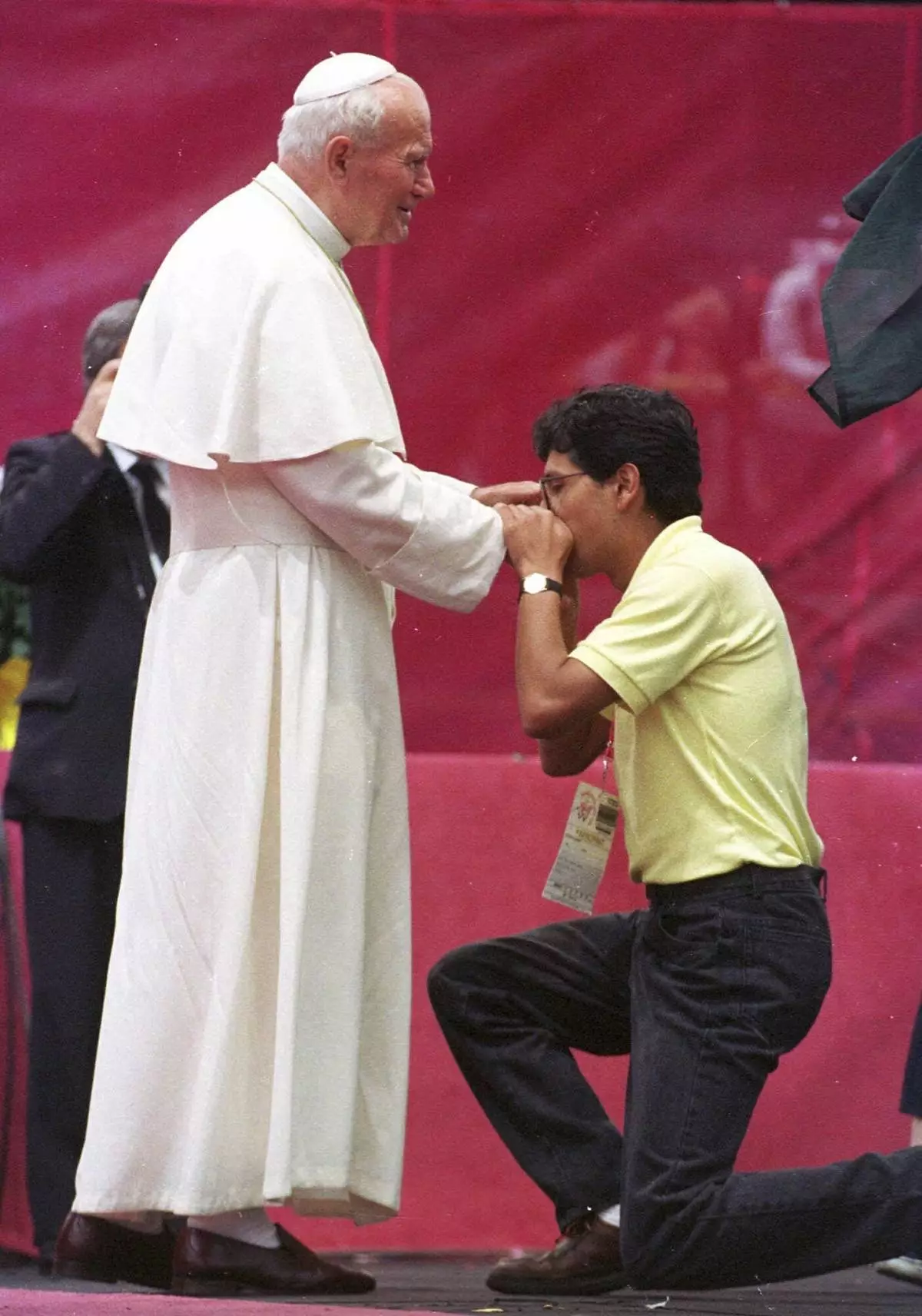

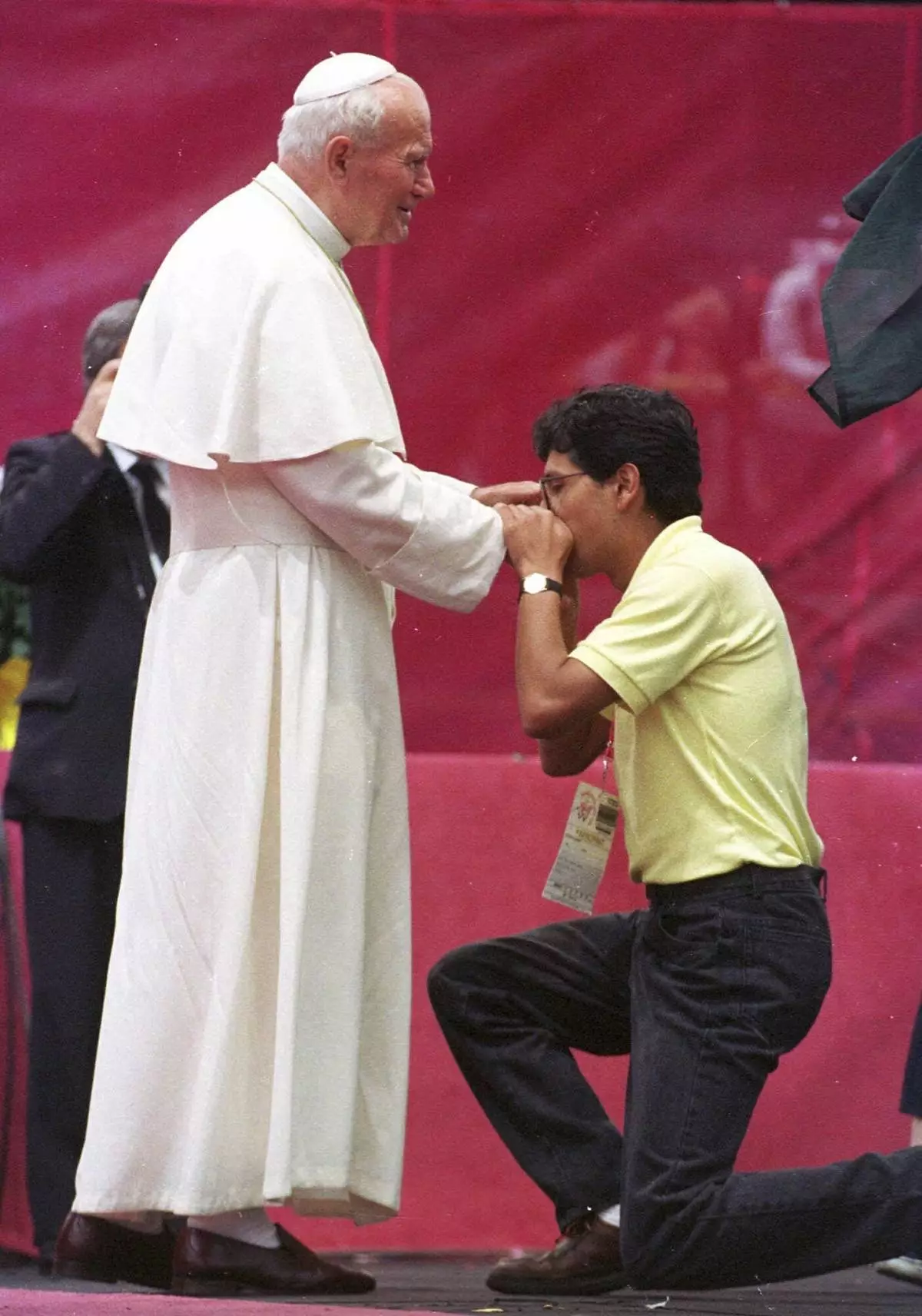

If this movement emerged from anywhere, it might be a now-demolished Denver football stadium and a borrowed military helicopter carrying in Pope John Paul II.

Some 500,000 people descended on Denver in 1993 for the Catholic festival World Youth Day. When the pope’s helicopter landed just outside Mile High Stadium, the ground shook from the stomping.

The pope, whose grandfatherly appearance belied an electric charisma, and who was beloved both for his kindness and his sternness, confronted an American church shaped by three decades of progressive change.

If the church is often best known to non-Catholics for its opposition to abortion, it had grown increasingly liberal since Vatican II. Birth control was quietly accepted in many parishes, and confession barely mentioned. Catholic social teaching on poverty suffused churches. Most priests traded in their cassocks for plain black shirts with Roman collars. Incense and Latin became increasingly rare.

On some issues, John Paul II agreed with these liberal-minded Catholics. He spoke against capital punishment and pushed for workers’ rights. He preached relentlessly about forgiveness – “the oxygen that purifies the air of hatred.” He forgave his own would-be assassin.

But he was also uncompromising on dogma, warning about change and cracking down on liberal theologians. He urged a return to forgotten rituals.

Catholics “are in danger of losing their faith,” he told crowds at the final Denver Mass, decrying abortion, drug abuse, and what he called “sexual disorders,” a barely veiled reference to growing acceptance of gay rights.

Across the nation, fervent young Catholics listened.

Newman Centers, which serve Catholic university students, became increasingly popular. So did FOCUS, a traditionalist organization working on American college campuses. Conservative Catholic media grew, particularly the cable TV network EWTN, a prominent voice for increased orthodoxy.

Today, conservative Catholic America has its own constellation of online celebrities aimed at young people. There’s Sister Miriam James, an ever-smiling nun in full habit who talks openly about her hard-partying college days. There’s Jackie Francois Angel, who speaks in shockingly frank detail about sex, marriage and Catholicism. There’s Mike Schmitz, a movie-star handsome Minnesota priest who exudes kindness while insisting on doctrine.

Even today, surveys show most American Catholics are far from orthodox. Most support abortion rights. The vast majority use birth control.

But increasingly, those Catholics are not in church.

In 1970, more than half of America’s Catholics said they went to Mass at least once a week. By 2022, that had fallen to 17%, according to CARA, a research center affiliated with Georgetown University. Among millennials, the number is just 9%.

Even as the U.S. Catholic population has jumped to more than 70 million, driven in part by immigration from Latin America, ever-fewer Catholics are involved in the church’s most important rites. Infant baptisms have fallen from 1.2 million in 1965 to 440,000 in 2021, CARA says. Catholic marriages have dropped by well over two-thirds.

The shrinking numbers mean that those who remain in the church have outsized influence compared with the overall Catholic population.

On the national level, conservatives increasingly dominate the U.S. Catholic Bishops Conference and the Catholic intellectual world. They include everyone from the philanthropist founder of Domino’s Pizza to six of the nine U.S. Supreme Court justices.

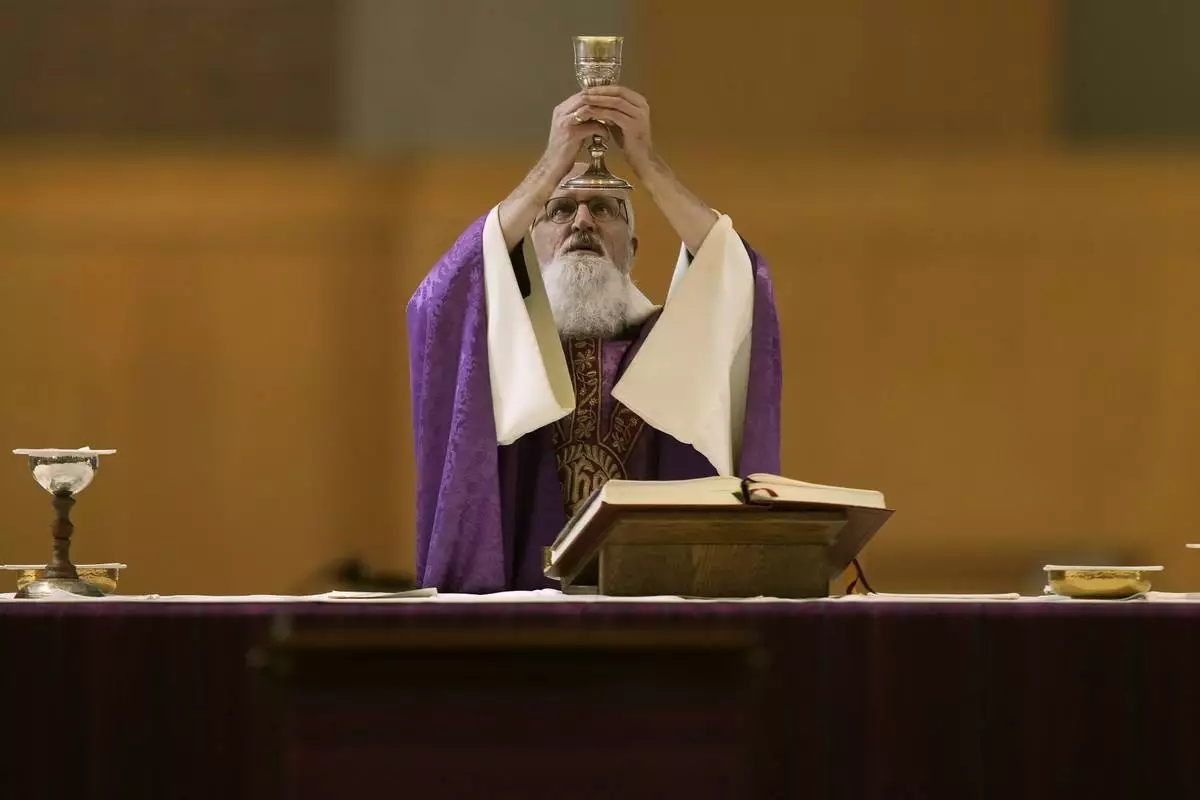

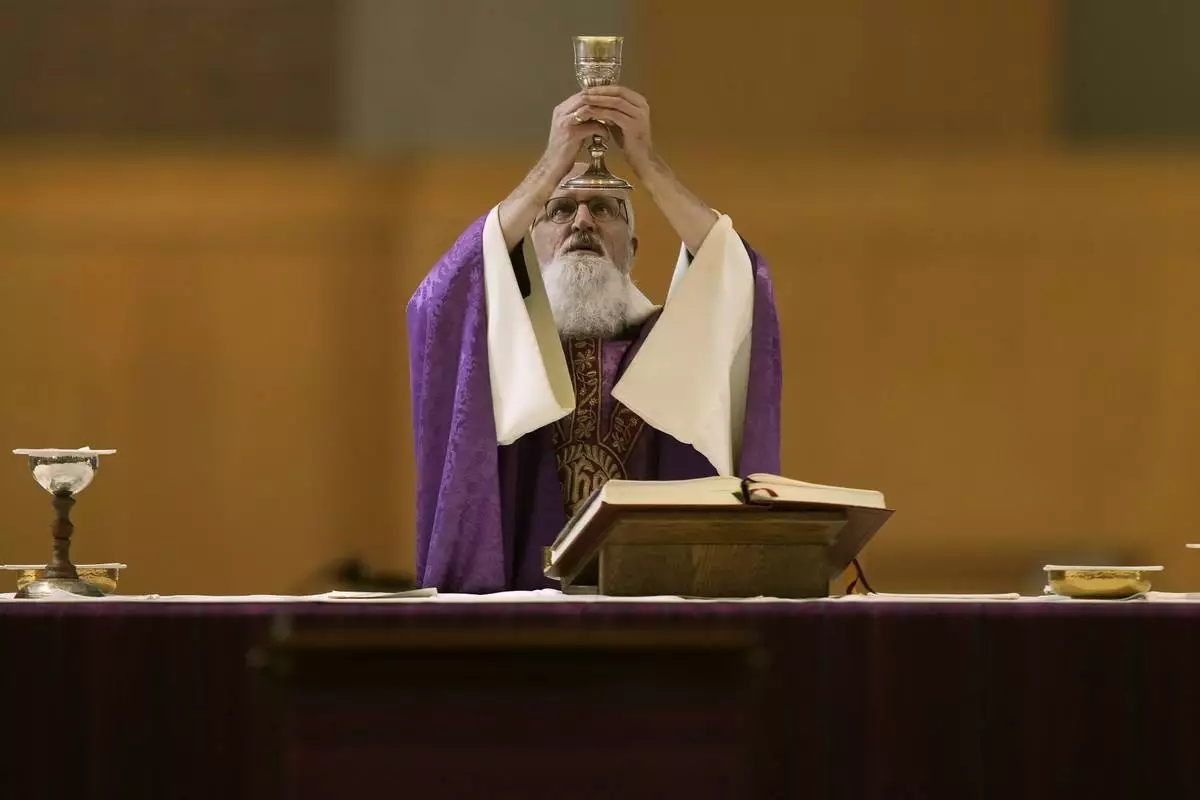

Then there’s the priesthood.

Young priests driven by liberal politics and progressive theology, so common in the 1960s and 70s, have “all but vanished,” said a 2023 report from The Catholic Project at Catholic University, based on a survey of more than 3,500 priests.

Today’s young priests are far more likely to believe that the church changed too much after Vatican II, tangling itself up in America’s rapidly shifting views on everything from women’s roles to LGBTQ people.

“There really aren’t very many liberals in the seminaries anymore,” said a young, recently ordained Midwestern priest. He spoke on condition of anonymity because of the turmoil that engulfed his parish after he began pressing for more orthodox services. “They wouldn’t feel comfortable.”

-----

Sometimes, the shift toward orthodoxy happens slowly. Maybe there’s a little more Latin sprinkled into Mass, or an occasional reminder to go to confession. Maybe guitars are relegated to Saturday evening services, or dropped completely.

And sometimes the changes come like a whirlwind, dividing parishes between those thirsting for a more reverent Catholicism and those who feel their spiritual home has been taken from them.

“You’d leave Mass thinking, ‘Holy cow! What just happened?’” said another ex-parishioner at St. Maria Goretti, whose family eventually left the church, describing the 2021 promotion of a new pastor, and a sudden focus on sin and confession.

Like many former parishioners, he spoke only on condition of anonymity, worried about upsetting friends still at the church. Diocesan clergy did not respond to requests for interviews.

“I’m a lifelong Catholic. I grew up going to church every Sunday,” he said. “But I’d never seen anything like this.”

The new outlook has spilled across America.

In churches from Minnesota to California, parishioners have protested changes introduced by new conservative priests. In Cincinnati, it came when the new priest abandoned gospel music and African drumming. In small-town North Carolina, it was an intense focus on Latin. In east Texas, it was a right-wing bishop forced out by the Vatican after accusing Pope Francis of undermining church teachings.

Each can seem like one more skirmish in the cultural and political battles tearing at America.

But the movement, whether called conservative or orthodox or traditionalist or authentic, can be hard to define.

It ranges from Catholics who want more incense, to Latin Mass adherents who have brought back ancient prayers that mention “the perfidious Jew.” There are right-wing survivalists, celebrity exorcists, environmentalists and a handful of quasi-socialists.

There’s the Catholic news outlet railing against the Vatican’s “wicked entourage,” and the small-town Wisconsin priest who traces COVID-19 to a century-old prophecy and warns of looming dictatorship. There’s the recent “Catholic Prayer for Trump,” a $1,000-a-plate dinner at the former president’s Mar-a-Lago resort, featuring a string of conspiracy theorists.

Yet the orthodox movement can also seem like a tangle of forgiveness and rigidity, where insistence on mercy and kindness mingle with warnings of eternity in hell.

Looming over the American divide is PopeFrancis, who has pushed the global church to be more inclusive, even as he toes the line on mostdogma.

The orthodox movement has watched him nervously from the first days of his papacy, angered by his more liberal views on issues like gay relationships and divorce. Some reject him entirely.

And the pope clearly worriesabout America.

The U.S. church has “a very strong reactionary attitude,” he told a group of Jesuits last year. “Being backward-looking is useless.”

You can find this new vision of Catholic America at Latin Masses in Milwaukee, the pews crowded with worshippers even at noon on a weekday. It’s in conferences held in California wine country, at reinvigorated parishes in Tennessee and prayer groups in Washington, D.C.

And it’s at a little Kansas college built high on a bluff above the Missouri River.

At first glance, nothing seems unusual about Benedictine College.

Students worry about unfinished essays and the complexities of dating. They wear cutoff shorts on warm autumn afternoons. Football is huge. The cafeteria food is mediocre.

But look deeper.

Because at Benedictine, Catholic teaching on contraception can slip into lessons on Plato, and no one is surprised if you volunteer for 3 a.m. prayers. Pornography, pre-marital sex and sunbathing in swimsuits are forbidden.

If these rules seem like precepts of a bygone age, that hasn’t stopped students from flocking to Benedictine and other conservative Catholic colleges.

At a time when U.S. college enrollment is shrinking, Benedictine’s expansion over the last 15 years has included four new residence halls, a new dining hall and an academic center. An immense new library is being built. The roar of construction equipment never seems to stop.

Enrollment, now about 2,200, has doubled in 20 years.

Students, many of whom grew up in conservative Catholic families, jokingly call it “the Benedictine bubble.” And it might be a window into the future of the Catholic Church in America.

In a deeply secular America, where an ever-churning culture provides few absolute answers, Benedictine offers the reassurance of clarity.

“We don’t all agree on everything, obviously,” said John Welte, a senior majoring in economics and philosophy. “But I would say everyone has an understanding of, like, truth.”

“There are certain things you can just know in your mind: This is right, and this is wrong.”

Sometimes, people here quietly admit, it goes too far. Like the students who loudly proclaim how often they go to Mass, or the young man who quit his classics course because he refused to read the works of ancient Greek pagans.

Very often, talk here echoes the 13th-century writings of St. Thomas Aquinas, who believed God could be found in truth, goodness and beauty. Sometimes, they say, that means finding God in strict tenets about sexuality. Sometimes in the haunting beauty of Gregorian chants.

“It’s a renewal of, like, some really, really good things that we might have lost,” said Madeline Hays, a pensive 22-year-old senior biology major.

She takes the church’s rules seriously, from pre-marital sex to confession. She can’t stand modern church architecture. She’s seriously considering becoming a nun.

But she also worries about poverty and America’s wastefulness and the way Americans –including herself – can find themselves slotted into the political divide without even knowing it.

She wrestles with her belief in an unerring Catholic doctrine that can see good people, including some of her own friends, as sinners.

Yet she doesn’t want change.

“The church wouldn’t be the church if it changed things it had set down as, 'This is infallible doctrine and this will not change through the ages,’” she said.

They understand that in Benedictine’s small, mostly closeted gay community. Like the young man, once deeply religious, who suffers in silence as people on campus casually throw around anti-gay slurs.

He’s thought many times of leaving, but generous financial aid keeps him here. And after many years, he’s accepted his sexuality.

He’s seen the joy that people can get from Benedictine, how some will move back to Atchison after graduation, just to stay close.

But not him.

“I don’t think I’ll come back to Atchison – not ever.”

For decades, the pews at St. Maria Goretti were filled with the families of plumbers, engineers and professors from the University of Wisconsin, just a couple miles up the road. The church is a well-kept island of Catholicism tucked into the leafy residential streets of one of America’s most liberal cities.

Like so many other parishes, it had been shaped by the ideals of the 1960s and 1970s. Poverty and social justice became tightly interwoven with sermons and parish life. Gay people felt welcome. Some of the church’s moral absolutes, like the contraception ban, became forgotten dogma.

Change arrived in 2003 with a new bishop, Robert C. Morlino, an outspoken conservative. Many liberals remember him as the man who lambasted the message of acceptance in the modern hymn, “All Are Welcome.”

His successor, Bishop Donald J. Hying, steers clear of public battles. But in many ways, he quietly carries on Morlino’s legacy, warning about “the tangled thinking of Modernism.”

In 2021, Hying named the Rev. Scott Emerson, a onetime top Morlino aide, as pastor of the Madison church.

Parishioners watched - some pleased, some uneasily - as their spiritual home was remodeled.

There was more incense, more Latin, more talk of sin and confession.

Emerson’s sermons are not all fire-and-brimstone. He speaks often about forgiveness and compassion. But his tone shocked many longtime parishioners.

Protection is needed, he said in a 2023 service, from “the spiritual corruption of worldly vices.” He has warned against critics – “the atheists, journalists, politicians, the fallen-away Catholics” – he said were undermining the church.

For some, Emerson’s changes were welcome.

“A lot of us were like, ’Hey, more confession! Sweet!” said Rouleau, who ran the parish young adult group. “Better music!”

But the parish – which in mid-2023 became part of a two-church “pastorate” amid a diocese-wide restructuring - was shrinking fast.

For decades, many traditional Catholics have wondered if the church would – and perhaps should – shrink to a smaller but more faithful core.

In ways, that’s how St. Maria Goretti looks today. The 6:30 a.m. Friday Mass, Rouleau says, is increasingly popular among young people. But once-packed Sunday Masses now have empty pews. Donations are down. School enrollment plunged.

Some who left have gone to more liberal parishes. Some joined Protestant churches. Some abandoned religion entirely.

“I’m not a Catholic anymore,” said Hammond, the woman who left when the church’s school began to change. “Not even a little bit.”

But Emerson insists the Catholic Church’s critics will be proven wrong.

“How many have laughed at the church, announcing that she was passe, that her days were over and that they would bury her?” he said in a 2021 Mass.

“The church,” he said, “has buried every one of her undertakers.”

Associated Press journalist Jessie Wardarski contributed to this report.

FILE - Pope Francis holds the book of the Gospels as he celebrates the Christmas Eve Mass in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Saturday, Dec. 24, 2016. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, File)

FILE - A painter outlines the Pope's nose on the side of a building in New York on Thursday, Aug. 27, 2015, a month before the visit of Pope Francis. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan, File)

FILE - Pope Francis waves to the crowd during a parade Saturday, Sept. 26, 2015, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke, Pool, File)

FILE - Pope Paul VI sits on his throne before the altar in far background in the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican, as he delivers his first message to the world June 22, 1963, the day after he was elected Pontiff. 79 Cardinals are standing left and right at the seats and tables where they sat during the Conclave that elected Pope Paul VI. At the Pope's right stands Msgr. Enrico Dante, Prefect of the Pontific Ceremonies, and at his left side Msgr. Salvatore Capoferri, Master of the Pontific Ceremonies. (AP Photo/Luigi Felici, File)

FILE - Pope John XXIII waves a hand in blessing at Roman Catholic Ecumenical Council at St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, Oct. 11, 1962. The Council opened earlier in the day. In the background is Monsignor Enrico Dante, prefect of the Vatican ceremonial office. (AP Photo/Raoul Fornezza, File)

FILE - St. Maria Goretti parishoner Anna Buss, 10, pauses in front of a shrine to Pope John Paul II before Mass Saturday, April 2, 2005, in Madison, Wis. (John Maniaci/Wisconsin State Journal via AP, File)

FILE - A World Youth Day participant kisses the ring of Pope John Paul II at Mile High Stadium in Denver on Aug. 12, 1993. (AP Photo/Jeff Robbins, File)

FILE - Pope John Paul II greets participants of World Youth Day as he arrives for Mass at Cherry Creek State Park in Aurora, Colo., Aug. 15, 1993. (AP Photo/Jeff Robbins, File)

FILE - Nuns gather in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican, Saturday, April 26, 2014. Pilgrims and faithful gathered in Rome the day before Sunday's ceremony where Pope Francis elevated John XXIII and John Paul II to sainthood. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti, File)

FILE - Youths wave goodbye to the helicopter carrying Pope John Paul II, as the Pontiff leaves the grounds of Tor Vergata after leading a Sunday Mass for some 2 million youths on Aug. 20, 2000. (AP Photo/Enric Marti, File)

FILE - Pictures of late Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI are distributed outside St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Tuesday, Jan. 3, 2023. For a second day, lines of people wanting to honor Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI 's service to the Catholic church snaked around St. Peter's Square on Tuesday to view the late retired pontiff's body. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

FILE - Pope Benedict XVI hoists a monstrance containing a Holy Host during a Corpus Domini celebration outside St. Mary Major Basilica to mark the feast of the Body and Blood of Christ, in Rome, Thursday, May 26, 2005. (AP Photo/Domenico Stinellis, File)

FILE - Pope Benedict XVI lies on the ground before the altar during a Good Friday ceremony for the Passion of Christ, inside St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Friday, April 6, 2007. (AP Photo/Danilo Schiavella, Pool, File)

FILE - Pope Benedict XVI touches the cross hanging around his neck as he meets journalists during the flight from Rome to Sao Paulo, Brazil, Wednesday, May 9, 2007. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

FILE - Pope Benedict XVI greets the faithful to deliver his "Urbi et Orbi" message, Latin for ''to the city and to the world", as he appears from the velvet-draped central balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Tuesday, Dec. 25, 2007. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, File)

FILE - Participants in the youth jubilee follow a night vigil led by Pope John Paul II, Saturday, Aug. 19, 2000, in Rome's suburb of Tor Vergata, for World Youth Day. (AP Photo/Pier Paolo Cito, File)

Benedictine College student Hannah Moore extinguishes candles after evening prayers with her roommates in a room which they converted to a chapel in the house they share Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

A woman sits alone before Catholic Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Oct. 29, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Benedictine College student Niki Wood looks through her prayer book before evening prayers with her roommates in the house they share Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Benedictine College students from left Ashley Lestone, Hannah Moore, Niki Wood, and Madeline Hays share a laugh as they look through their prayer books before evening prayers in a room which they converted to a chapel in the house they share Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. Hays takes the church’s rules seriously, from pre-marital sex to confession. She’s seriously considering becoming a nun. But she also worries about poverty and America’s wastefulness and the way Americans –including herself – can find themselves slotted into the political divide without even knowing it. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Benedictine College student Niki Wood looks through her prayer book before evening prayers with her roommates in the house they share Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. In a deeply secular America, where an ever-churning culture provides few absolute answers, Benedictine offers the reassurance of clarity. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Catholics pray during Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Rev. Gabriel Landis officiates a Catholic Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

A woman and child kneel during Catholic Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Oct. 29, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Brothers Leven Barton, left, Florian Rumpza, center, and Angelus Atkinson, sing in Latin during Catholic Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Rev. Gabriel Landis prepares Communion during a Catholic Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Students leave after attending a Catholic Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. Many At a time when U.S. college enrollment is shrinking, the conservative Catholic school has expanded over the last 15 years. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

People receive communion during Catholic Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. Many Students, many of whom grew up in conservative Catholic families, jokingly call it “the Benedictine bubble.” And it might be a window into the future of the Catholic Church in America. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

A man prays during Catholic Mass at Benedictine College Sunday, Oct. 29, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. Many Catholic parishes are becoming more conservative as they move away from modernizing reforms that swept the church more than 50 years ago. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Benedictine College students, from left, Madeline Hays, Niki Wood, Ashley Lestone and Hannah Moore gather for evening prayers in a room which they converted to a chapel in the house they share Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in Atchison, Kan. Across the U.S., the Catholic church is undergoing an immense shift. Generations of Catholics who embraced the modernizing tide are increasingly giving way to religious conservatives who believe the church has been twisted by change. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)