The 606 men refusing to leave an Australian immigration camp in Papua New Guinea were without power and many of their toilets on Wednesday as reports emerged saying one of them had resorted to harming himself while others needed urgent medical treatment.

In this undated photo released by Refugee Action Coalition, refugees and asylum seekers hold up banners during a protest at the Manus Island immigration detention centre in Papua New Guinea. (Refugee Action Coalition via AP)

The camp inside a Manus Island navy base was declared closed Tuesday afternoon based on the Papua New Guinea Supreme Court's ruling last year that Australia's policy of detaining asylum seekers there was illegal and unconstitutional. But the men who have stayed at the camp on Lombrun Navy Base fear for their safety in the alternative shelters available in the nearby town of Lorengau because of threats from locals.

Click to Gallery

In this undated photo released by Refugee Action Coalition, refugees and asylum seekers hold up banners during a protest at the Manus Island immigration detention centre in Papua New Guinea. (Refugee Action Coalition via AP)

In this photo made from Australia Broadcasting Coporation video made on Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2017, asylum seekers protesting the possible closure of their detention center, on Manus Island, Paua New Guinea. (Australia Broadcasting Coroporation via AP)

This photo made from Australia Broadcasting Corporation video taken on Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2017, shows asylum seekers protesting the possible closure of their detention center on Manus Island, Paua New Guinea. (Australia Broadcasting Corporation via AP)

This photo made from Australia Broadcasting Corporation video taken on Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2017, shows housing of asylum seekers protesting the possible closure of their detention center, on Manus Island, Paua New Guinea. (Australia Broadcasting Corporation via AP)

The Sydney-based Refugee Action Coalition said the removal of electricity generators Wednesday morning left the camp without power, including toilets that operate on electrical pumps. They still have tap water, though the coalition says it isn't drinkable.

As the asylum seekers faced a second nervous night at the now-unguarded facility amid ongoing fears of violence from locals, an Iranian man living there, Behrouz Boochani, tweeted: "A refugee has harmed himself with a razor. He cut his wrist and chest. Physically he's good now but mentally is out of control."

In this photo made from Australia Broadcasting Coporation video made on Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2017, asylum seekers protesting the possible closure of their detention center, on Manus Island, Paua New Guinea. (Australia Broadcasting Coroporation via AP)

In another tweet, Boochani said: "Some refugees are very sick. They need urgent medical treatment. They have been physically sick for a long time. There is no support for them." He added later that "a Rohingya refugee with epilepsy is sick now."

Boochani also tweeted that Papua New Guinea immigration officials had sent a bus to the center Wednesday morning to take refugees to their alternative accommodation in Lorengau, but that "the refugees are still refusing to go. Immigration is saying (it's) your choice".

The Refugee Action Coalition has applied to the Supreme Court for an injunction stopping the closure of the camp. Coalition spokesman Ian Rintoul said the first night without security staff guarding the residents had at least passed peacefully.

"The men are sitting tight for the moment," Rintoul said. "The situation isn't great, but at least there were no attacks during the night."

This photo made from Australia Broadcasting Corporation video taken on Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2017, shows asylum seekers protesting the possible closure of their detention center on Manus Island, Paua New Guinea. (Australia Broadcasting Corporation via AP)

Rintoul said some locals brought food and drinking water to the perimeter fence, some selling it to the men, others donating it.

Papua New Guinea officials had said the facility would be returned to defense forces on Wednesday and that anyone remaining would be considered to be trespassing on a military base. However, that failed to happen on Wednesday, as a standoff continued.

Australia's acting prime minister, Julie Bishop, standing in for Malcolm Turnbull during his visit to Israel, said it made "no sense" for detainees to remain at the center, but she could not guarantee their safety if they left the camp.

"The Papua New Guinea government is a sovereign government and is responsible for law and order and security on their islands in their nation," Bishop told ABC radio.

This photo made from Australia Broadcasting Corporation video taken on Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2017, shows housing of asylum seekers protesting the possible closure of their detention center, on Manus Island, Paua New Guinea. (Australia Broadcasting Corporation via AP)

She said food, water, electricity and medical services would be provided at alternative accommodation on the island.

For four years, Australia has paid Papua New Guinea, its nearest neighbor, and the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru to house asylum seekers who attempt to reach the Australian coast by boat. They are Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar, Afghans, Iranians, Sri Lankans and other nationalities.

Australia has recognized that many of the asylum seekers are refugees who cannot return to their homelands, but it refuses to resettle anyone who tried to reach the country by boat in a policy it credits with dissuading such dangerous ocean crossings. Some whose refugee claims were denied have been forcibly sent home.

But Australia and Papua New Guinea still disagree on who has responsibility for those Australia has recognized as refugees yet won't accept on its own soil.

The United States has resettled 54 of them in recent weeks and is considering taking almost 1,200 more.

The men are free to come and go from the Manus Island camp, which is no longer a detention center since the court ruling, but they've reported robberies and violence directed at them when they go into the community.

Of the 606 men, some 440 have been deemed to be legitimate refugees, while the remainder are categorized as non-refugees, including around 50 who have refused to cooperate with the determination process as they say they were unlawfully transferred to Papua New Guinea.

Papua New Guinea authorities have deployed extra police to the town of Lorengau, where the three new housing centers are located. A protest of about 100 people earlier this week demanded Australia take back the men and they not live in the community.

Australian opposition Greens senator Nick McKim, who is on Manus Island, has labeled Immigration Minister Peter Dutton a "monster" over his handling of the closure of the center. He warned that deaths were inevitable and that Dutton "could have blood on his hands."

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina (AP) — Venezuela's release of detainees Thursday briefly brought relief and guarded optimism to a country consumed by uncertainty.

But it was another, less covered news event far afield that some Venezuelan advocates said offered their only real shot at justice as long as the government of former President Nicolás Maduro remained intact.

A federal court in Argentina Thursday ordered the judiciary to press on with investigations into alleged crimes against humanity committed by members of Venezuela’s national guard, turning down an appeal by a former officer who argued that Argentina had no jurisdiction to go after Venezuelan officials.

Judges demanded that Argentina pursue the case under the doctrine of universal jurisdiction, whereby human rights violators of any nationality can be charged in any country, no matter where the crimes were committed, according to a copy of the ruling obtained by The Associated Press.

Lawyers said the timing of the court decision sent a message.

After attacking Venezuela and seizing its president to stand trial in the U.S., the Trump administration surprised Venezuelans and the international community by endorsing Delcy Rodríguez, Maduro’s handpicked deputy who oversaw the feared intelligence service, to lead the transition.

“We cannot lose our focus at this moment,” said Ignacio Jovtis, director for Latin America at InterJust, an organization seeking accountability for international crimes and representing three of the Venezuelan plaintiffs. “Victims in Venezuela are still waiting for justice.”

Whatever relief Venezuelans felt seeing Maduro in handcuffs Saturday “has nothing to do with the process of bringing truth and reparation to victims and trying perpetrators for crimes against humanity,” he added.

It's no coincidence that this investigation is progressing in Argentina, experts say, a country that has learned a thing or two about prosecuting a strongman from its groundbreaking efforts bringing to justice the brutal military dictatorship that oversaw the killing or disappearance of as many as 30,000 Argentines from 1976 to 1983.

Over 1,200 ex-army officers have been tried and sentenced in Argentina, many to life in prison, and hundreds more await trial.

As one of just a handful of countries whose law permits the investigation of crimes-against-humanity cases beyond its borders, Argentina has increasingly taken center stage in lawsuits ranging from the torture of dissidents under Franco’s dictatorship in Spain to atrocities committed by the military against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

Frustrated by the impunity in their home country and the limits of the laboriously slow International Criminal Court, Venezuelans have taken their quests for justice to Argentina.

Thursday's criminal complaint accuses 14 Venezuelan National Guard officers of human rights abuses dating to 2014, when security forces under Maduro aggressively stamped out anti-government protests, arresting, torturing and killing suspected dissidents.

Argentina began investigating the allegations in 2023. A catalogue of torture was spelt out in court as former detainees and families of protesters killed in the crackdown flew to Buenos Aires to give testimony.

Last year, Justo José Noguera Pietri — a key defendant and former commander of Venezuela's national guard — asked the Argentine judiciary to dismiss the case and void the outstanding arrest warrant against him. A federal appeals court denied his requests Thursday, citing the “extreme gravity” of the alleged crimes.

“For us, this is not a symbolic investigation,” Jovtis said. "We want the perpetrators to go before an Argentine judge and be tried here.”

A separate Venezuelan case filed recently in Argentina targets ousted President Maduro, hard-line Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello and other top officials still in power. An Argentine judge asked for the extradition of the defendants this week.

Argentine President Javier Milei, a right-wing ideologue and President Donald Trump’s most loyal Latin American ally, joyously celebrated the capture of the leader he long lambasted as the ultimate political evil.

A staple on the global conservative speaking circuit, Milei has long been friendly with Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado and last October attended the ceremony in Norway that awarded her the Nobel Peace Prize.

As U.S. Special Forces whisked Maduro out of Venezuela, Milei issued a triumphant statement calling for “everything to be set right and for the true president to take office, Edmundo González Urrutia " — the candidate widely considered the legitimate winner of the country's turbulent 2024 election.

But as Trump froze out Machado and elevated Rodríguez, Milei changed his tune.

All mentions of democracy were scrubbed from Argentina's official statements on Venezuela. In their Tuesday telephone call about the situation, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and his Argentine counterpart spoke only about “cooperation to confront narcoterrorism.”

On the streets of Caracas, the initial jolt of euphoria after Maduro's capture last Saturday has rapidly worn off, turning into a more familiar, nagging dread. Pro-government paramilitary groups known as “colectivos” have been deployed across Caracas.

“Right now in Venezuela, everybody’s erasing their phones because 'colectivos' are checking to see if you’ve been tweeting or looking at anything anti-government,” said Ricardo Hausmann, a professor of the practice of international political economy at the Harvard Kennedy School. “There is too much talk about oil and money, but for Venezuelans to do anything, they need rights.”

Trump, preoccupied with the prospect of extracting Venezuela’s oil riches, had only praise for Rodríguez's government in an interview with Fox News late Thursday.

“They’ve been great,” he said of Maduro's loyalists, hailing the release of detainees. “Everything we’ve wanted they’ve given us.”

Some Venezuelans had other thoughts.

“The repressive machinery has not stopped, so we don’t know if there is any real change,” said Luis Carlos Díaz, a prominent Venezuelan journalist who was briefly detained in 2019.

Even more than Thursday's prisoner releases, he said, the case in Argentina gave him hope.

“That’s why it’s essential that other countries keep judicial processes open for Venezuela,” Díaz said. “If we had to wait for the dictatorship to fall before seeking justice, many of us would die first."

Associated Press writer Sergio Farella contributed to this report.

Riot police arrive to El Helicoide, the headquarters of Venezuela's intelligence service and detention center, in Caracas, Venezuela, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, after National Assembly President Jorge Rodriguez said the government would release Venezuelan and foreign prisoners. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

Venezuelans celebrate at the Obelisk in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Saturday, Jan. 3, 2026, after U.S. President Donald Trump announced that President Nicolas Maduro had been captured and flown out of Venezuela. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

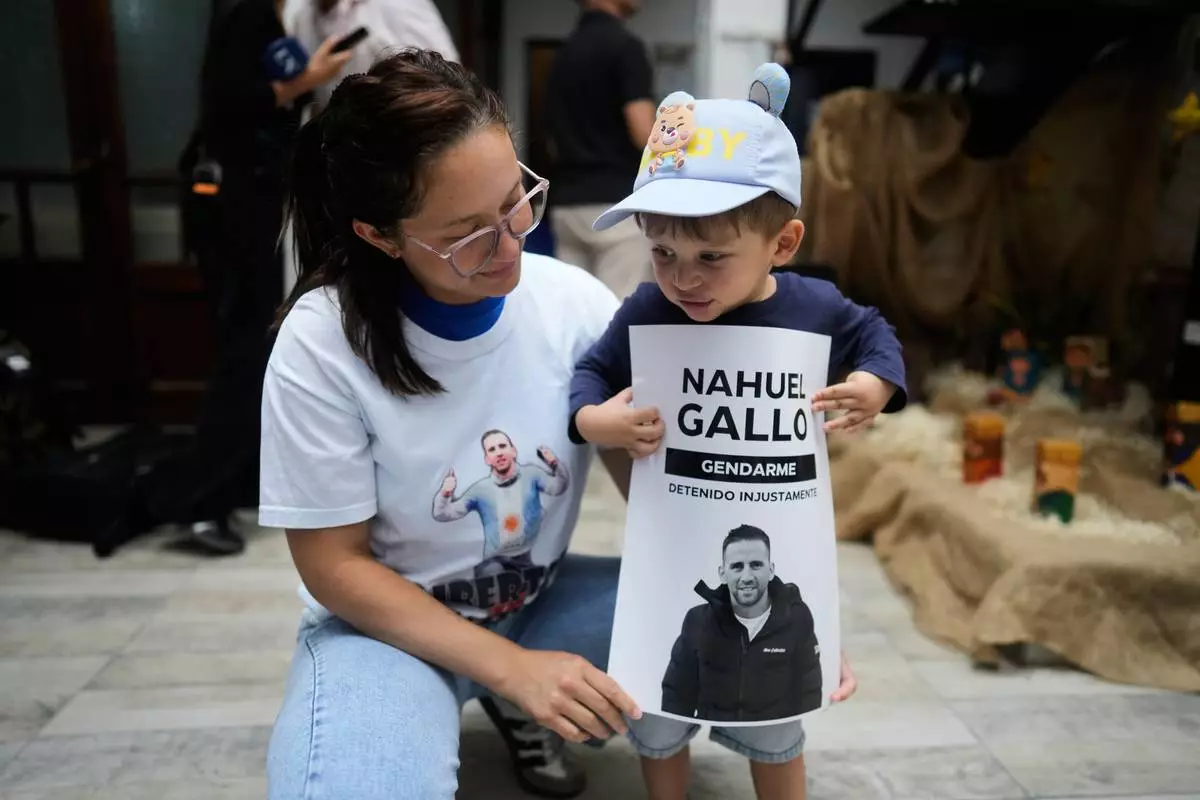

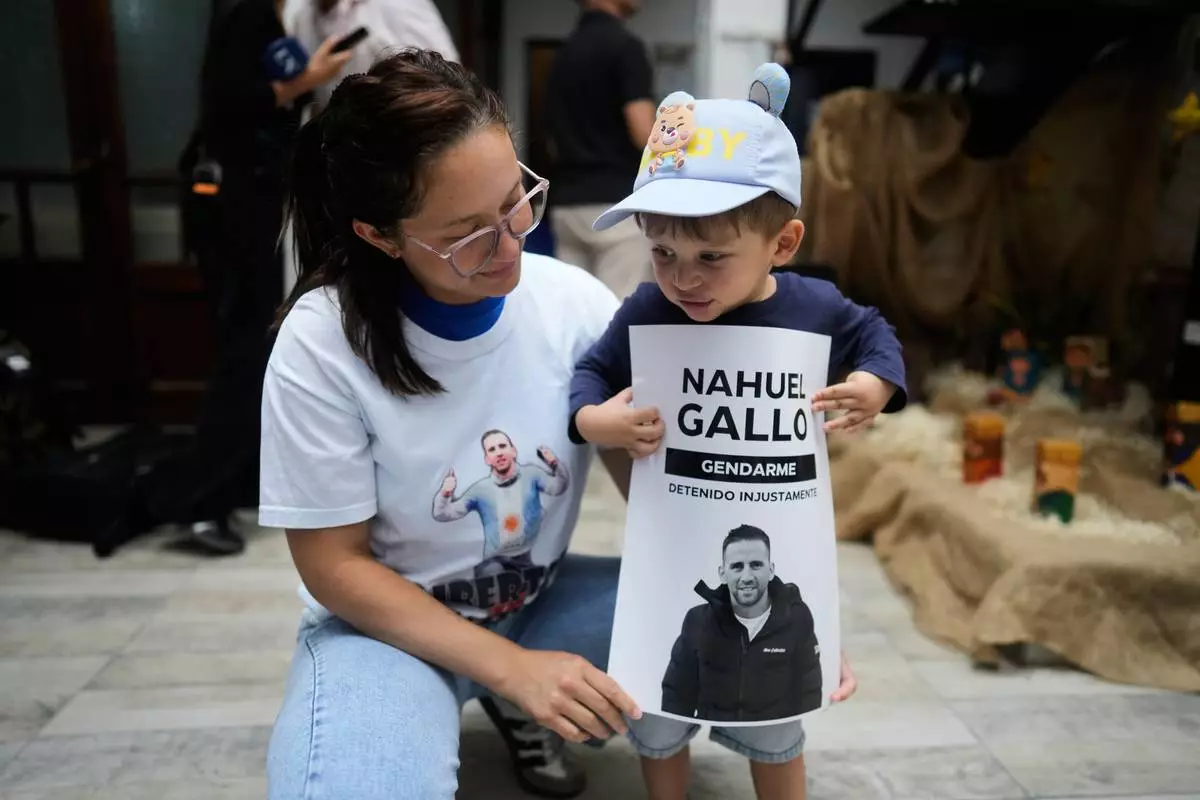

Maria Alexandra Gomez, girlfriend of detained Argentine officer Nahuel Agustin Gallo, stands with their son Victor during a gathering of friends and relatives of people detained in Venezuela at a community center where they wait for news of their loved ones' release in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, after Venezuelan authorities said the they would release Venezuelan and foreign prisoners. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)