With flags, patriotic tunes and a troupe of cheerleaders, Russia wants to throw the biggest party at the Pyeongchang Olympics.

Never mind that Russia's team must compete in neutral uniforms. Never mind that 45 Russian athletes were excluded from the games early Friday. In the Sports House on the Gangneung seafront, the doping scandals never happened.

Click to Gallery

With flags, patriotic tunes and a troupe of cheerleaders, Russia wants to throw the biggest party at the Pyeongchang Olympics.

The house opened Friday afternoon with rousing speeches from Russia's ambassador to South Korea and former Olympic champions. For them, Russia is now and forever a sports superpower.

"It's great because there's a place where they're always waiting for you, where they're always happy to see you," said Dmitry Davydov, a fan from St. Petersburg who was wrapped in the national flag. "It's a little corner of Russia far from home."

They considered rebranding as the Red Machine House in tribute to great Soviet hockey teams of the Cold War era, but settled on the blander Sports House, run by a Russian sports development fund best known for regularly gifting luxury cars to Olympic medalists in Kremlin ceremonies.

Russian singers and cheerleaders perform during the opening of the Sports House, set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

A girl looks at photos of Russia's president Vladimir Putin during the opening of the Sports House set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

Fans of Russia cheer at the opening of the Sports House, set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

Russian cheerleaders perform during the opening of the Sports House, set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

The house opened Friday afternoon with rousing speeches from Russia's ambassador to South Korea and former Olympic champions. For them, Russia is now and forever a sports superpower.

"Russia is a full participant in the Olympic Games and Russia can show its sporting power," ambassador Alexander Timonin said. "We believe in our athletes, we are proud of them, and we hope that they can achieve their very best sporting results and bring glory to our great motherland."

The "Sports House" name may be bland, but it's definitely Russian inside. There is a traditional samovar of tea, a folk choir, even the dress in which figure skater Adelina Sotnikova won the gold medal in Sochi in 2014. One side of the hall is adorned with photographs of President Vladimir Putin meeting South Korean dignitaries.

Olympic champions of decades past sat in a VIP zone upstairs, overlooking a hall where Russian fans — and some local Russophiles — mingled around a buffet.

Russian cheerleaders perform during the opening of the Sports House, set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

"It's great because there's a place where they're always waiting for you, where they're always happy to see you," said Dmitry Davydov, a fan from St. Petersburg who was wrapped in the national flag. "It's a little corner of Russia far from home."

Davydov arrived fresh from watching the officially-neutral "Olympic Athletes from Russia" compete in figure skating.

"My hands are red with clapping and I'm losing my voice," he said.

When Russian sports officials first rented the cavernous Aqua Wedding Hall for the Pyeongchang Olympics, they wanted to brand it the Russian Fans' House. Then the International Olympic Committee banned the Russian team from the games for doping, inviting only selected athletes to compete as neutral Olympians.

Russian officials flirted with hosting their own medal ceremonies for athletes in the house, but feared it could provoke the wrath of the IOC.

Fans of Russia cheer at the opening of the Sports House, set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

They considered rebranding as the Red Machine House in tribute to great Soviet hockey teams of the Cold War era, but settled on the blander Sports House, run by a Russian sports development fund best known for regularly gifting luxury cars to Olympic medalists in Kremlin ceremonies.

There were no current Russian Olympians at the opening — 168 will compete in Pyeongchang — but organizers plan to host any medalists later for media events. The IOC didn't respond when asked if that complies with its rules.

For Tatiana Volosozhar, a figure skater who won gold for Russia in 2014, the house should be a beacon of hope for Russian athletes in tough circumstances.

"Everything's very joyful, though the events this morning weren't joyful for some Olympians," Volosozhar said. "But our athletes are here to compete and they have to win."

Russian girls stand next to photos of Russia's President Vladimir Putin during the opening of the Sports House, set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

Russian singers and cheerleaders perform during the opening of the Sports House, set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

A girl looks at photos of Russia's president Vladimir Putin during the opening of the Sports House set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

Fans of Russia cheer at the opening of the Sports House, set up to support the Russian delegation of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 9, 2018. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

HELENA, Mont. (AP) — BNSF Railway attorneys told a Montana jury Friday that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of an asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program.

Attorneys for the company say the corporate predecessors of the railroad, owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate, didn't know the vermiculite they hauled over decades from a nearby mine was filled with hazardous microscopic asbestos fibers or that asbestos was dangerous.

BNSF attorney Chad Knight said the railroad could only be held liable if it could have foreseen the health hazards of asbestos based on information available decades ago when the alleged exposures happened.

“In the 50s, 60s and 70s no one in the public suspected there might be health concerns,” Knight said.

The case in federal civil court is the first of numerous lawsuits against the Texas-based railroad corporation to reach trial over its past operations in Libby, Montana. Current and former residents of the small town near the U.S.-Canada border want BNSF held accountable for its alleged role in asbestos exposure that health officials say has killed several hundred people and sickened thousands.

The seven-member jury met briefly Friday and planned to resume deliberations on Monday morning. They were instructed to decide if the railroad was at fault in the deaths and if so, the amount of damages to award to their estates. If the jurors find that the railroad should also face punitive damages, a separate hearing would determine that amount.

Looming over the proceedings is W.R. Grace & Co., a chemical company that operated a mountaintop vermiculite mine 7 miles (11 kilometers) outside of Libby until it was closed 1990. The Maryland-based company played a central role in Libby's tragedy and has paid significant settlements to victims.

U.S. District Court Judge Brian Morris has referred to the the chemical company as “the elephant in the room” in the BNSF trial. He reminded jurors several times that the case was about the railroad's conduct, not W.R. Grace's separate liability.

How much W.R. Grace revealed about the asbestos dangers to Texas-based BNSF and its corporate predecessors has been sharply disputed. The plaintiffs argued that railroad higher-ups were aware, but that workers on the ground in Libby were left out of the loop.

“We're here to make a party that accepts zero responsibility accept an appropriate amount of responsibility,” plaintiffs' attorney Mark Lanier said. “This is the fault of the bigwigs in the corporate office.”

The judge instructed the jury it could only find the railroad negligent based on its actions in the Libby Railyard, not for hauling the vermiculite.

The railroad said it was obliged under law to ship the vermiculite, which was used in insulation and for other commercial purposes. It said W.R. Grace employees had concealed the health hazards from the railroad.

Former railroad workers said during testimony and in depositions that they knew nothing about the risks of asbestos. They said Grace employees were responsible for loading the hopper cars, plugging the holes of any cars leaking vermiculite and occasionally cleaned up material that spilled in the rail yard.

The estates of the two deceased plaintiffs have argued that the W.R. Grace’s actions don’t absolve BNSF of its responsibility for failing to clean up the vermiculite that spilled in the railyard in the heart of the community.

Their attorneys said BNSF should have known about the dangers because Grace put signs on rail cars carrying vermiculite warning of potential health risks. They showed jurors an image of a warning label allegedly attached to rail cars in the late 1970s that advised against inhaling the asbestos dust because it could cause bodily harm.

Family members of Tom Wells and Joyce Walder testified that their lives ended soon after they were diagnosed with mesothelioma. The families said the dust blowing from the rail yard sickened and killed them.

In a March 2020 video of Wells played for jurors and recorded the day before he died, he lay in a home hospital bed, struggling to breathe.

“I’ve been placed in a horrible spot here, and the best chance I see at release — relief for everybody — is to just get it over with,” he said. “It’s just not something I want to try and play hero through because I don’t think that there’s a miracle waiting.”

The Environmental Protection Agency descended on Libby after the 1999 news reports. In 2009 it declared in Libby the nation’s first ever public health emergency under the federal Superfund cleanup program.

The pollution in Libby has been cleaned up, largely at public expense. Yet the long timeframe over which asbestos-related diseases develop means people previously exposed are likely to continue getting sick for years to come, health officials say.

Brown reported from Billings, Montana.

FILE - Environmental cleanup specialists work at one of the last remaining residential asbestos cleanup sites in Libby, Montana, in mid-September. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (Kurt Wilson/The Missoulian via AP, File)

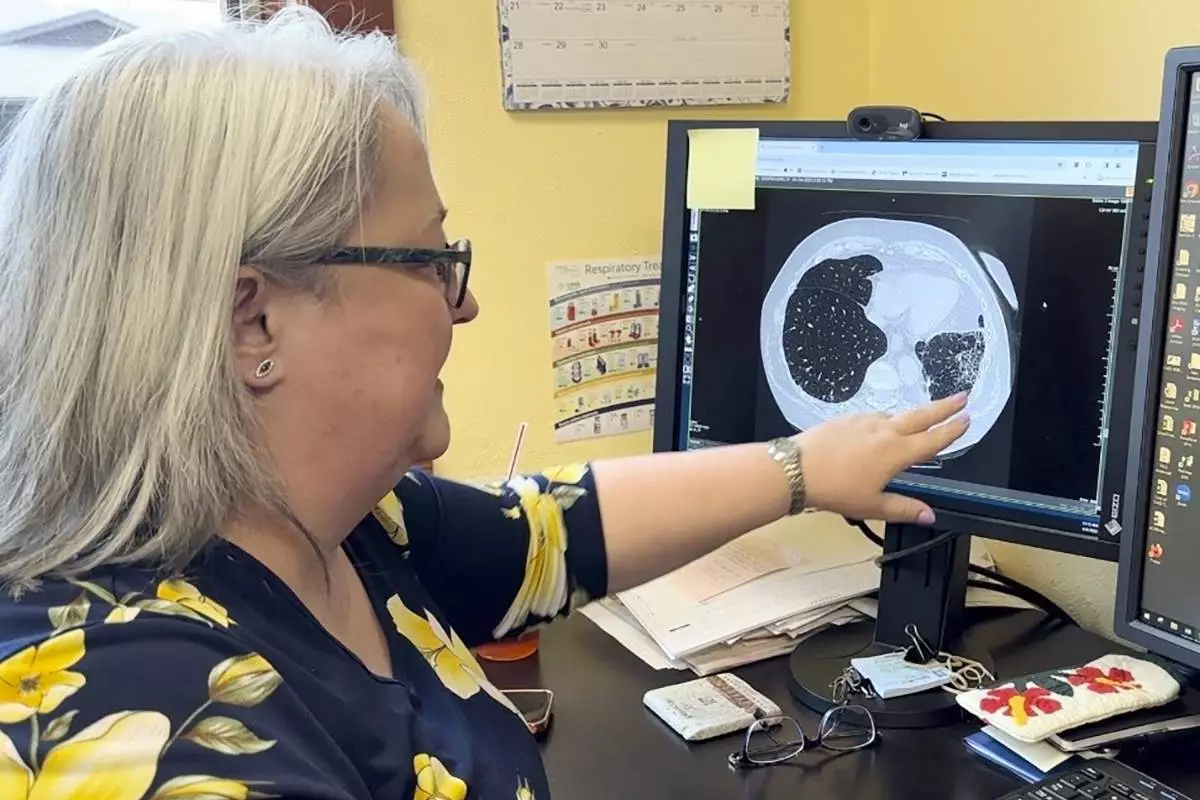

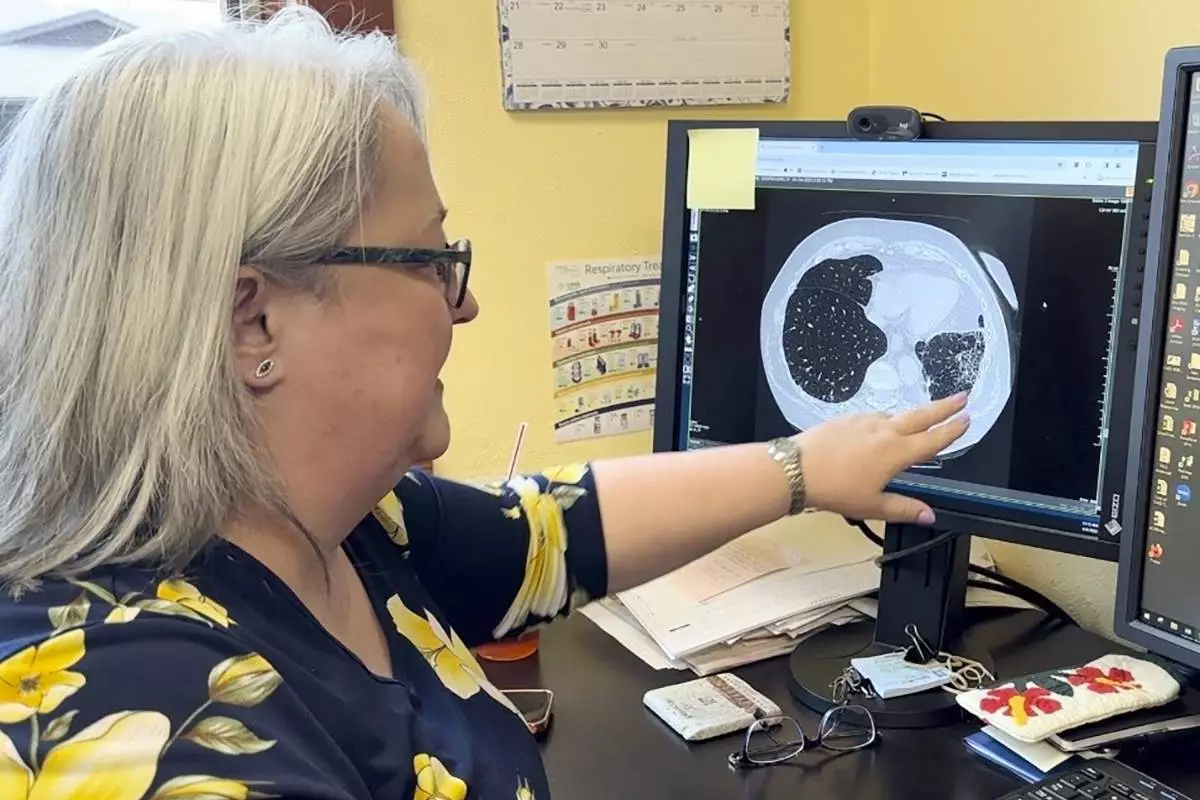

FILE - Dr. Lee Morissette shows an image of lungs damaged by asbestos exposure, at the Center for Asbestos Related Disease, Thursday, April 4, 2024, in Libby, Mont. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown, File)

FILE - In this April 27, 2011, file photo, the entrance to downtown Libby, Mont., is seen. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown, File)