After two weeks of Olympic competition, the "Olympic Athletes from Russia" finally have a gold medal.

Alina Zagitova won the women's figure skating title Friday to become the first Russian to win a Winter Olympic event since the doping-hit 2014 Sochi Games.

Alina Zagitova of the Olympic Athletes of Russia waves after winning g the gold medal during the women's free figure skating final in the Gangneung Ice Arena at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 23, 2018. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

"I was trying with all my strength to ignore it but I couldn't," Zagitova said of Russia's lack of gold. "I was really worried because I knew I didn't have the right to make a mistake. I had to skate clean and show my maximum, but I'm so happy I could."

The Russians have one gold, five silver and eight bronze medals at the Pyeongchang Games as of Friday, putting them behind Belarus and Italy on gold medals (the key measure used in Russia), and behind France on total medals.

Gold medalist in the women's free figure skating Russian athlete Alina Zagitova poses during the medals ceremony at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 23, 2018. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

For a traditional winter sports superpower that prided itself on topping the Sochi medals table — even if many athletes were later accused of doping — the wait for gold has been unfamiliar and unpleasant.

Zagitova, who was only 11 during the Sochi Olympics and has never been suspected of doping, didn't hear the Russian national anthem at her medal ceremony. Instead, the Olympic anthem was played and the Olympic flag flew because Russia is officially suspended from the games.

The International Olympic Committee instead invited some from the country to compete in neutral uniforms, which is why Zagitova accepted her medal in a muted gray coat with the inscription "Olympic Athlete from Russia."

Medalists in the women's free figure skating, from right, Russian athlete Evgenia Medvedeva, silver, Russian athlete Alina Zagitova, gold, and Canada's Kaetlyn Osmond, bronze, pose during their medals ceremony at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 23, 2018. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

To many Russian fans, that status is degrading. To many of Russia's critics over doping, it's a symbolic punishment for a country which should have been banned entirely.

Asked about whether she would be sad not to hear the Russian anthem play, Zagitova avoided the issue.

"Can I not answer that question?" she said.

The Russian medal count at the Pyeongchang Games has been low because of the IOC vetting process, bad luck, and — once again — doping. Curler Alexander Krushelnitsky and his wife, Anastasia Bryzgalova, won bronze in mixed doubles, but gave up the medal Thursday after Krushelnitsky failed a doping test.

Alina Zagitova of the Olympic Athletes of Russia celebrates on the podium after winning the gold medal in the women's free figure skating final in the Gangneung Ice Arena at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Gangneung, South Korea, Friday, Feb. 23, 2018. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip)

Russia sent 168 athletes to South Korea, making it one of the largest teams at the games. However, the team didn't contain some top athletes, including world cross-country ski champion Sergei Ustyugov and short-track speedskater Viktor Ahn. The IOC said it couldn't be confident they were clean. On the day of the opening ceremony, it won a key legal battle upholding that argument.

Still, Russian officials could have sent more athletes in some events but chose not to. According to the Court of Arbitration for Sport, Russia chose to leave 40 quota places unfilled rather than send athletes who weren't first choice, which meant it didn't have enough in some sports simply to enter the relays.

Another issue is that Russia's Winter Olympians competed in Sochi with lavish funding from the government. With the country's moment in the Olympic spotlight over, sports like biathlon and bobsled have struggled for money.

There's also been a wave of infighting in some events like luge, where one Russian was sent home after missing the podium and accusing team staff of favoritism toward his main domestic rival. Injuries played a role in some sports, and in others the Russians simply weren't good enough for gold.

It was a long path to the games for Evgenia Medvedeva, who won silver in figure skating alongside Zagitova, her friend and training partner.

It was Medvedeva who was chosen by Russian sports officials to make their case to the IOC in December, when a blanket ban on Russia was possible. When she skated Friday, she was introduced as an "Olympic Athlete from Russia" as Russian fans cheered and waved the tricolor she's forbidden to wear.

Asked how a Russian 1-2 finish feels without her country's flag, Medvedeva asked for a moment to think before replying.

"People know who we are," she said, "and the spectators in the stands showed it today."

HELENA, Mont. (AP) — BNSF Railway attorneys told a Montana jury Friday that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of an asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program.

Attorneys for the company say the corporate predecessors of the railroad, owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate, didn't know the vermiculite they hauled over decades from a nearby mine was filled with hazardous microscopic asbestos fibers or that asbestos was dangerous.

BNSF attorney Chad Knight said the railroad could only be held liable if it could have foreseen the health hazards of asbestos based on information available decades ago when the alleged exposures happened.

“In the 50s, 60s and 70s no one in the public suspected there might be health concerns,” Knight said.

The case in federal civil court is the first of numerous lawsuits against the Texas-based railroad corporation to reach trial over its past operations in Libby, Montana. Current and former residents of the small town near the U.S.-Canada border want BNSF held accountable for its alleged role in asbestos exposure that health officials say has killed several hundred people and sickened thousands.

The seven-member jury met briefly Friday and planned to resume deliberations on Monday morning. They were instructed to decide if the railroad was at fault in the deaths and if so, the amount of damages to award to their estates. If the jurors find that the railroad should also face punitive damages, a separate hearing would determine that amount.

Looming over the proceedings is W.R. Grace & Co., a chemical company that operated a mountaintop vermiculite mine 7 miles (11 kilometers) outside of Libby until it was closed 1990. The Maryland-based company played a central role in Libby's tragedy and has paid significant settlements to victims.

U.S. District Court Judge Brian Morris has referred to the the chemical company as “the elephant in the room” in the BNSF trial. He reminded jurors several times that the case was about the railroad's conduct, not W.R. Grace's separate liability.

How much W.R. Grace revealed about the asbestos dangers to Texas-based BNSF and its corporate predecessors has been sharply disputed. The plaintiffs argued that railroad higher-ups were aware, but that workers on the ground in Libby were left out of the loop.

“We're here to make a party that accepts zero responsibility accept an appropriate amount of responsibility,” plaintiffs' attorney Mark Lanier said. “This is the fault of the bigwigs in the corporate office.”

The judge instructed the jury it could only find the railroad negligent based on its actions in the Libby Railyard, not for hauling the vermiculite.

The railroad said it was obliged under law to ship the vermiculite, which was used in insulation and for other commercial purposes. It said W.R. Grace employees had concealed the health hazards from the railroad.

Former railroad workers said during testimony and in depositions that they knew nothing about the risks of asbestos. They said Grace employees were responsible for loading the hopper cars, plugging the holes of any cars leaking vermiculite and occasionally cleaned up material that spilled in the rail yard.

The estates of the two deceased plaintiffs have argued that the W.R. Grace’s actions don’t absolve BNSF of its responsibility for failing to clean up the vermiculite that spilled in the railyard in the heart of the community.

Their attorneys said BNSF should have known about the dangers because Grace put signs on rail cars carrying vermiculite warning of potential health risks. They showed jurors an image of a warning label allegedly attached to rail cars in the late 1970s that advised against inhaling the asbestos dust because it could cause bodily harm.

Family members of Tom Wells and Joyce Walder testified that their lives ended soon after they were diagnosed with mesothelioma. The families said the dust blowing from the rail yard sickened and killed them.

In a March 2020 video of Wells played for jurors and recorded the day before he died, he lay in a home hospital bed, struggling to breathe.

“I’ve been placed in a horrible spot here, and the best chance I see at release — relief for everybody — is to just get it over with,” he said. “It’s just not something I want to try and play hero through because I don’t think that there’s a miracle waiting.”

The Environmental Protection Agency descended on Libby after the 1999 news reports. In 2009 it declared in Libby the nation’s first ever public health emergency under the federal Superfund cleanup program.

The pollution in Libby has been cleaned up, largely at public expense. Yet the long timeframe over which asbestos-related diseases develop means people previously exposed are likely to continue getting sick for years to come, health officials say.

Brown reported from Billings, Montana.

FILE - Environmental cleanup specialists work at one of the last remaining residential asbestos cleanup sites in Libby, Montana, in mid-September. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (Kurt Wilson/The Missoulian via AP, File)

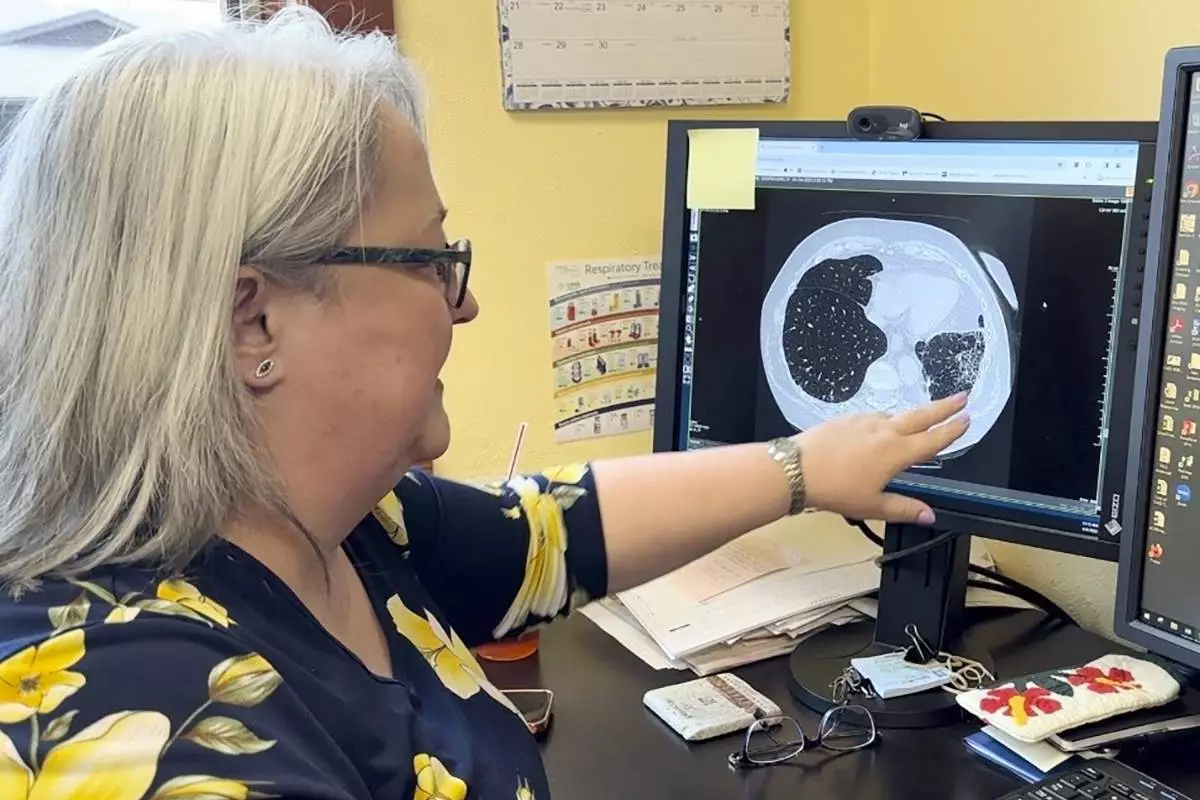

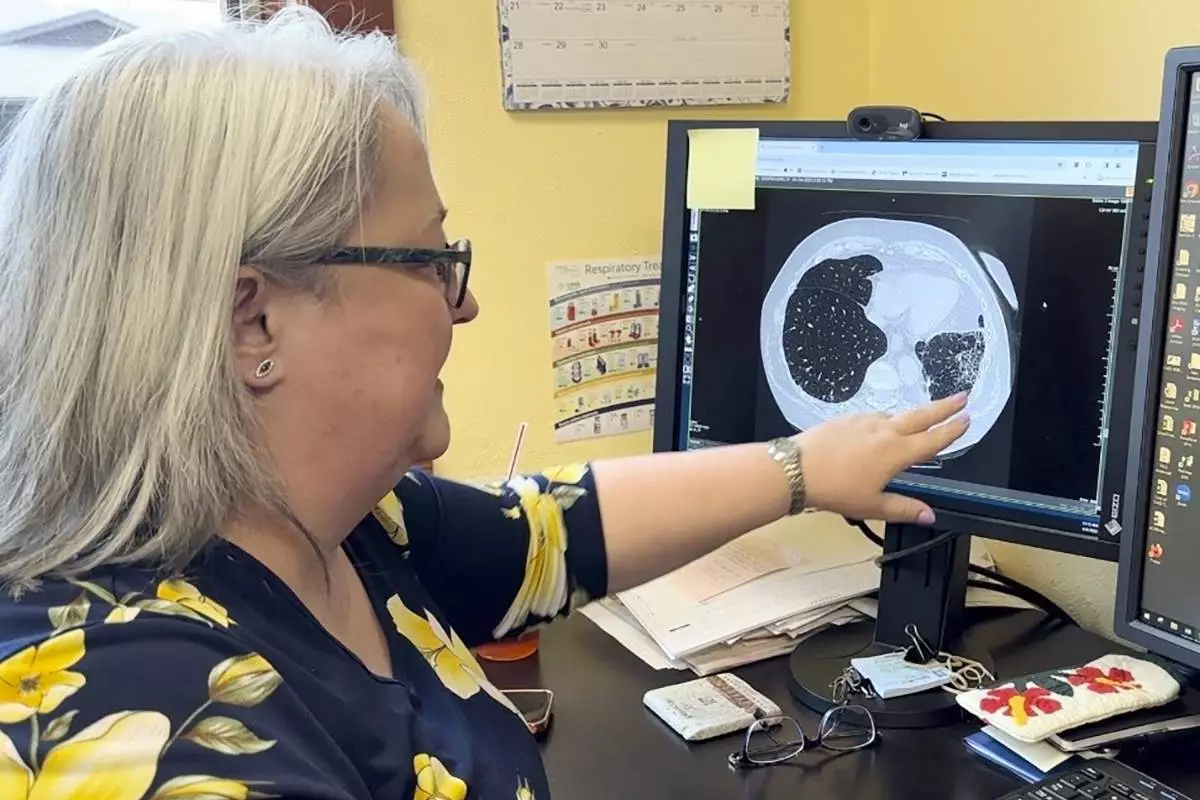

FILE - Dr. Lee Morissette shows an image of lungs damaged by asbestos exposure, at the Center for Asbestos Related Disease, Thursday, April 4, 2024, in Libby, Mont. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown, File)

FILE - In this April 27, 2011, file photo, the entrance to downtown Libby, Mont., is seen. BNSF Railway attorneys are expected to argue before jurors Friday, April 19, 2024, that the railroad should not be held liable for the lung cancer deaths of two former residents of the asbestos-contaminated Montana town, one of the deadliest sites in the federal Superfund pollution program. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown, File)