South Korean President Moon Jae-in has always wanted to lead the diplomacy aimed at ending the North Korean nuclear crisis, even as he was overshadowed in his first year in office by a belligerent standoff between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un.

Moon now has his wish granted as he prepares for a meeting in late April with Kim and basks in the international glow of having engineered another upcoming summit — previously thought wildly unlikely — between the American and North Korean leaders.

It doesn't mean the decades-long effort to thwart the North's nuclear ambition is settled, but it's clear that Moon is having a diplomatic moment. He's popular at home, and abroad he has emerged as a reliable intermediary between North Korea and the United States, enemies that spent the last year threatening each other with total destruction.

FILE - In this March 7, 2018, file photo, people watch a TV screen showing images of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, right, South Korean President Moon Jae-in, center, and U.S. President Donald Trump at the Seoul Railway Station in Seoul, South Korea. South Korean President Moon Jae-in has always wanted to lead the diplomacy aimed at ending the North Korean nuclear crisis, even as he was overshadowed in his first year in office by a belligerent standoff between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un. Korean letters on the screen read: "Thawing Korean Peninsula." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, File)

Here's a look at how Moon set up the summits and the challenges that lie ahead:

PATIENCE

Since taking office last May, the liberal Moon has maintained that South Korea needs to lead on the North Korea issue.

In part, it was a matter of national pride for many South Koreans, who liken their country's geopolitical situation to "a shrimp stuck between whales" — the whales being the U.S. and China.

Moon initially found little room to maneuver diplomatically.

The Trump administration was wary about Moon pushing for greater ties with North Korea even as Pyongyang carried out its biggest ever nuclear test explosion and test-fired intercontinental ballistic missiles. So Moon was forced to go more hard-line than he probably wanted and to join Trump's sanctions and pressure campaign against Pyongyang.

Moon ordered provocative precision-guided missile tests immediately after North Korean weapons tests, something that even his conservative predecessors didn't do. He also allowed the United States to install a high-tech missile defense system despite strong oppositions by China.

All the while, though, he kept working to reach out to the North.

The Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, would prove to be a major opportunity.

Moon may have learned how to balance the alliance with Washington and his outreach to the North from his time as chief of staff for late liberal President Roh Moo-hyun, who often had awkward ties with President George W. Bush over North Korea.

"Moon realized why relations with the U.S. suffered during the Roh government so he would know very well how to deal with the U.S.," said Lee Daewoo, an analyst at the private Sejong Institute in South Korea, who pointed out that Moon often gives Trump credit for bringing the North to talks.

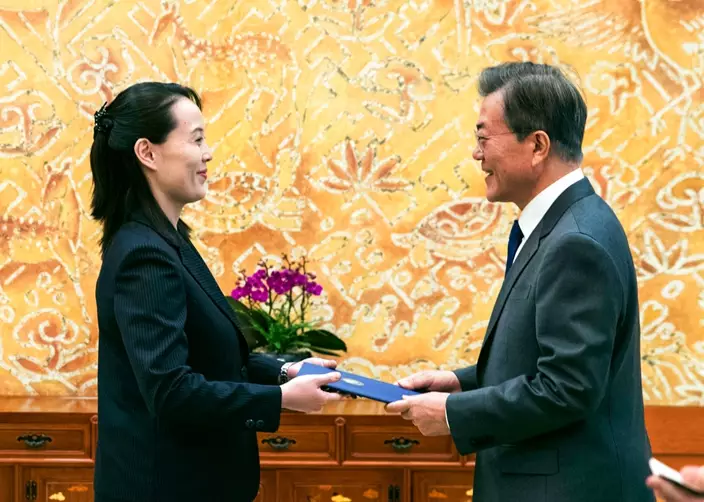

FILE - In this Feb. 10, 2018, file photo, South Korean President Moon Jae-in, right, receives a letter from Kim Yo Jong, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un's sister, at the presidential Blue House in Seoul, South Korea. South Korean President Moon Jae-in has always wanted to lead the diplomacy aimed at ending the North Korean nuclear crisis, even as he was overshadowed in his first year in office by a belligerent standoff between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un. (Kim Ju-sung/Yonhap via AP, File)

SPEED

The speed with which the two summits were set up shocked many, in part because of the period of intense animosity that came before.

The two Koreas have held leaders' talks only twice since the peninsula's 1945 division. There's been no such contact ever between sitting U.S. and North Korean leaders.

The process this time was linked to the Olympics. In January, North and South Korea had their first dialogue in two years to discuss cooperation for the February games. The rivals agreed to march together to open the games and to field their first joint Olympic team in women's hockey.

Kim sent his younger sister Kim Yo Jong to the opening ceremony, making her the first member of the North's ruling Kim family to visit South Korea since the end of the 1950-53 Korean War.

The U.S.-North Korea summit talks were brokered by Moon's envoys, who met with Kim Jong Un during a March 5-6 Pyongyang trip. They then brought Kim's offer to talk to Trump, who accepted the proposal.

Moon called the summit deals a "miracle."

"The world is paying attention," Moon told advisers Monday. "The fate of the Republic of Korea and the Korean Peninsula depends on whether we can seize on these opportunities."

FILE - In this March 5, 2018 file photo, provided by the North Korean government, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, front right, shakes hands with South Korean National Security Director Chung Eui-yong after Chung gave Kim the letter from South Korean President Moon Jae-in, in Pyongyang, North Korea. South Korean President Moon Jae-in has always wanted to lead the diplomacy aimed at ending the North Korean nuclear crisis, even as he was overshadowed in his first year in office by a belligerent standoff between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un. Independent journalists were not given access to cover the event depicted in this image distributed by the North Korean government. The content of this image is as provided and cannot be independently verified. Korean language watermark on image as provided by source reads: "KCNA" which is the abbreviation for Korean Central News Agency. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP, File)

HURDLES

There is still a chance the summit between Kim and Trump never happens.

Pyongyang's state media haven't even officially confirmed or denied that such talks were agreed to. The two sides are also far apart on what details would be up for discussion.

It's unknown what nuclear disarmament measures Kim might offer, what rewards he'll demand and whether Trump will agree.

North Korea will be very reluctant to completely abandon a nuclear program that it's spent decades building despite toughening international sanctions. Nuclear weapons are the core of Kim's authoritarian rule, with the young leader promoting the so-called "Byungjin" policy of simultaneously bolstering his nuclear arsenal and improving the economy.

One step the North might take is to offer to freeze or scrap its long-range nuclear missile program, which has worried U.S. officials who think Kim might soon acquire the ability to fire nuclear warheads at the U.S. mainland.

Trump, for his part, has said America demands complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization. The North has said denuclearization of the peninsula can be possible when the U.S. completely pulls out its 80,000 troops from South Korea and Japan and stops annual military drills with South Korea that it claims are an invasion rehearsal.

FILE - In this Feb. 9, 2018, file photo, North Korea's Hwang Chung Gum and South Korea's Won Yun-jong carriy the flag during the opening ceremony of the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea. South Korean President Moon Jae-in has always wanted to lead the diplomacy aimed at ending the North Korean nuclear crisis, even as he was overshadowed in his first year in office by a belligerent standoff between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

FALLOUT

Just as he was praised for setting up the summit, Moon could also be in the crosshairs should the talks fall apart or not bear fruit.

Moon would possibly face criticism from U.S. and South Korean conservatives that his overtures only helped North Korea buy time to perfect its nuclear program.

"It wasn't a bad attempt to draw Kim Jong Un into talks via the Olympics ... but we still worked as a messenger for North Korea and I think that's become a diplomatic risk,"said Go Myong-Hyun of the Seoul-based Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

But Lee at the Sejong Institute said any breakdown in talks shouldn't be blamed on the mediator.

And even if the talks fall through this time, Lim Eul Chul at South Korea's Kyungnam University said improved Korean ties could provide future opportunities to bring Pyongyang and Washington to the negotiating table.