Iraq has detained or imprisoned at least 19,000 people accused of connections to the Islamic State group or other terror-related offenses, and sentenced more than 3,000 of them to death, according to an analysis by The Associated Press.

The mass incarceration and speed of guilty verdicts raise concerns over potential miscarriages of justice — and worries that jailed militants are recruiting within the general prison population to build new extremist networks.

FILE - In this Oct. 3, 2017 file photo, a Kurdish security officer orders a displaced man from Hawija to sit down as they try to determine if the men being held were associated with the Islamic State group, at a Kurdish screening center in Dibis, Iraq. (AP Photo/Bram Janssen, File)

The AP count is based partially on an analysis of a spreadsheet listing all 27,849 people imprisoned in Iraq as of late January, provided by an official who requested anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media. Thousands more also are believed to be held in detention by other bodies, including the Federal Police, military intelligence and Kurdish forces. Those exact figures could not be immediately obtained.

The AP determined that 8,861 of the prisoners listed in the spreadsheet were convicted of terrorism-related charges since the beginning of 2013 — arrests overwhelmingly likely to be linked to the Islamic State group, according to an intelligence figure in Baghdad.

In addition, another 11,000 people currently are being detained by the intelligence branch of the Interior Ministry, undergoing interrogation or awaiting trial, a second intelligence official said. Both intelligence officials spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to brief the press.

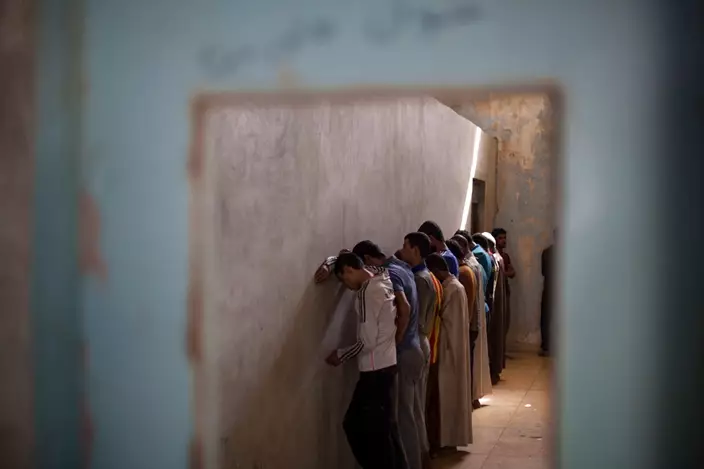

FILE - In this Oct. 3, 2017 file photo, displaced men from Hawija stand facing a wall in order not to see security officers, who will try to determine if they were associated with the Islamic State group, at a Kurdish screening center in Dibis, Iraq. (AP Photo/Bram Janssen, File)

"There's been great overcrowding ... Iraq needs a large number of investigators and judges to resolve this issue," Fadhel al-Gharwari, a member of Iraqi's parliament-appointed human rights commission, told the AP.

Al-Gharwari said many legal proceedings have been delayed because the country lacks the resources to respond to the spike in incarcerations.

Large numbers of Iraqis were detained during the 2000s, when the U.S. and Iraqi governments were battling Sunni militants, including al-Qaida, and Shiite militias. In 2007, at the height of the fighting, the U.S. military held 25,000 detainees. The spreadsheet obtained by the AP showed that about 6,000 people arrested on terror charges before 2013 still are serving those sentences.

But the current wave of detentions has hit the Iraqi justice system much harder because past arrests were spread out over a much longer period and the largest numbers of detainees were held by the American military, with only a portion sent to Iraqi courts and the rest released.

FILE - In this Oct. 3, 2017 file photo, a blindfolded suspected Islamic State militant stands against a wall at a Kurdish screening center in Dibis, Iraq. (AP Photo/Bram Janssen, File)

Human Rights Watch warned in November that the broad use of terrorism laws meant those with minimal connections to the Islamic State group are caught up in prosecutions alongside those behind the worst abuses. The group estimated a similar number of detainees and prisoners — about 20,000 in all.

"Based on all my meetings with senior government officials, I get the sense that no one — perhaps not even the prime minster himself — knows the full number of detainees," said Belkis Wille, the organization's senior Iraq researcher.

Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, who is running to retain his position in national elections slated for May, has repeatedly called for accelerated death sentences for those charged with terrorism.

The spreadsheet analyzed by the AP showed that 3,130 prisoners have been sentenced to death on terrorism charges since 2013.

Since 2014, about 250 executions of convicted IS members have been carried out, according to the Baghdad-based intelligence official. About 100 of those took place last year, a sign of the accelerating pace of hangings.

The United Nations has warned that fast-tracking executions puts innocent people at greater risk of being convicted and executed, "resulting in gross, irreversible miscarriages of justice."

The rising number of those detained and imprisoned reflects the more than four-year fight against the Islamic State group, which first formed in 2013 and conquered nearly a third of Iraq and neighboring Syria the next year.

FILE - In this Oct. 3, 2017 file photo, displaced men from Hawija sit facing a wall in order not to see security officers, who will try to determine if they were associated with the Islamic State group, at a Kurdish screening center in Dibis, Iraq. (AP Photo/Bram Janssen, File)

Iraqi and Kurdish forces, backed by a U.S.-led coalition, eventually rolled the group back on both sides of the border, regaining nearly all of the territory by the end of last year.

Throughout the fighting, Iraq has pushed thousands of IS suspects through trials in counterterrorism courts. Trials witnessed by the AP and human rights groups often took no longer than 30 minutes.

The vast majority were convicted under Iraq's Terrorism Law, which has been criticized as overly broad.

Asked about the process, Saad al-Hadithi, a government spokesman, said, "The government is intent that every criminal and terrorist receive just punishment."

The largest concentration of those with IS-related convictions is in Nasiriyah Central Prison, about 200 miles (320 kilometers) southeast of Baghdad, a sprawling maximum-security complex housing more than 6,000 people accused of terrorism-related offenses.

Cells designed to hold two prisoners now hold six, according to a prison official who spoke on condition of anonymity in line with regulations. The official said overcrowding makes it difficult to segregate prisoners charged with terrorism and that an inadequate number of guards means IS members are openly promoting their ideology inside the prison.

Though prisoners at Nasiriyah were banned last year from giving sermons and recruiting fellow inmates, the official said he still witnesses prisoners circulating extremist religious teachings.

In wards holding mostly terror-related convicts, high-ranking IS members have banned prisoners from watching television. Many refuse to eat meat from the cafeteria, believing it hasn't been prepared according to religious guidelines, the prison official said.

The relative free rein for extremists is reminiscent of Bucca Prison, a now-closed facility that the U.S. military ran in southern Iraq in the 2000s.

The facility proved a petri dish where militant detainees mingled — including the man who now leads the Islamic State group, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who spent months there, joining with other militants who became prominent in the group.

Iraqi officials say they have taken steps to prevent a repeat of the Bucca phenomenon.

"We will never allow Bucca to happen again," said an Interior Ministry officer overseeing the detention of IS suspects in the Mosul area, also speaking on condition of anonymity in line with regulations.

"The Americans freed their captives; under Iraq, they will all receive the death penalty," he said.

Cellphone signal jammers are installed at prisons holding IS suspects. But in Nasiriyah, the prison official said inmates appear to remain in contact with the outside.

He recounted how just days after a guard disciplined a senior IS member in the prison, the man threatened the guard's family, listing the names and ages of his children.

The imprisonments hit hard among Iraq's Sunni Arab minority, threatening to worsen tensions with the Shiite-dominated government. The community was both the pool that IS drew recruits from and the population most brutally victimized by its rule.

Mass incarcerations under former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki led to widespread resentment among Sunnis, helping fuel the growth of IS.

FILE - In this Oct. 3, 2017 file photo, displaced men from Hawija stand facing a wall in order not to see security officers, who will try to determine if they were associated with the Islamic State group, at a Kurdish screening center in Dibis, Iraq. (AP Photo/Bram Janssen, File)

The head of the International Red Cross, an organization that regularly visits prison and detention facilities in Iraq, warned that mass detentions often incite future cycles of violence.

"It's the tortures, the ill treatments, the continuous long-term bad conditions in detentions which have radicalized a lot of actors which we find again as armed actors on the battlefield," ICRC President Peter Maurer said during a recent visit to Iraq.