Wet and muddy from their trek across the Mexican border, immigrant children say they sat or lay on the cold, concrete floor of the immigration holding centers where they were taken.

It was hard to sleep with lights shining all night and guards kicking their feet, they say. They were hungry, after being given what they say were frozen sandwiches and smelly food.

Younger children cried in caged areas where they were crammed in with teens, and they clamored for their parents. Toilets were filthy, and running water was scarce, they say. They waited, unsure and frightened of what the future might bring.

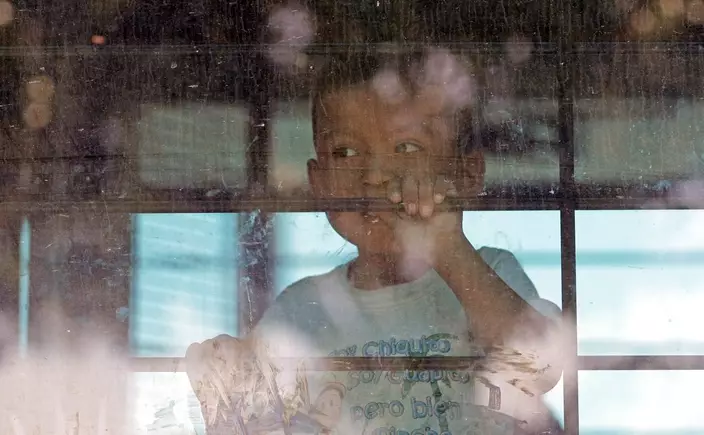

File - In this June 23, 2018, file photo, an immigrant child looks out from a U.S. Border Patrol bus leaving as protesters block the street outside the U.S. Border Patrol Central Processing Center in McAllen, Texas. Immigrant children described hunger, cold and fear in a voluminous court filing about the facilities where they were held in the days after crossing the border. Advocates fanned out across the southwest to interview more than 200 immigrant parents and children about conditions in U.S. holding facilities, detention centers and a youth shelter. The accounts form part of a case over whether the government is complying with a longstanding settlement over the treatment of immigrant youth in custody. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip, File)

"I didn't know where my mother was," said Griselda, 16, of Guatemala, who entered the U.S. with her mother in the McAllen, Texas, area. "I saw girls ask where their mothers were, but the guards would not tell them."

The children's descriptions of various facilities are part of a voluminous and at times scathing report filed in federal court this week in Los Angeles in a case over whether the Trump administration is meeting its obligations under a long-standing settlement governing how young immigrants should be treated in custody.

Dozens of volunteer lawyers, interpreters and other legal workers fanned out across the Southwest in June and July to interview more than 200 immigrant parents and children in holding facilities, detention centers and a youth shelter.

FILE - In this June 17, 2018 file photo provided by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, people who've been taken into custody related to cases of illegal entry into the United States, sit in one of the cages at a facility in McAllen, Texas. Immigrant children described hunger, cold and fear in a voluminous court filing about the facilities where they were held in the days after crossing the border. Advocates fanned out across the southwest to interview more than 200 immigrant parents and children about conditions in U.S. holding facilities, detention centers and a youth shelter. The accounts form part of a case over whether the government is complying with a longstanding settlement over the treatment of immigrant youth in custody. (U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Rio Grande Valley Sector via AP)

Advocates said the government isn't complying with the decades-old Flores agreement, which lays out detention conditions and release requirements for immigrant children.

"They have spoken out loud and clear, and what they've said is they are experiencing enforced hunger, enforced dehydration, enforced sleeplessness," said Peter Schey, an attorney for the children who has asked the court to appoint a special monitor to enforce the agreement. "They are terrorized, and I think it is time for the courts and the public to hear their voices."

The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees immigration and border enforcement, did not immediately comment. But in their own reports to the court last month, government monitors said that immigration authorities were complying with the settlement agreement.

In his report, Henry Moak Jr., juvenile coordinator for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, documented the air temperature as appropriate at a number of border facilities and said he drank the water himself from 5-gallon (19-liter) containers at a processing center in McAllen.

He said some children and parents told him they disliked the food and weren't sure the water was drinkable, but there were no allegations the food was spoiled.

FILE - In this Sunday, June 17, 2018, file photo provided by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, people who've been taken into custody related to cases of illegal entry into the United States rest in one of the cages at a facility in McAllen, Texas. Immigrant children described hunger, cold and fear in a voluminous court filing about the facilities where they were held in the days after crossing the border. Advocates fanned out across the southwest to interview more than 200 immigrant parents and children about conditions in U.S. holding facilities, detention centers and a youth shelter. The accounts form part of a case over whether the government is complying with a longstanding settlement over the treatment of immigrant youth in custody. (U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Rio Grande Valley Sector via AP, File)

At the Yuma station in Arizona, he said he tried the water there, too, and, "I can confirm the water fountains worked and the water tasted clean."

The litany of complaints compiled by advocates comes after a global outcry drove the Trump administration to stop separating immigrant families at the border. Authorities are now reuniting parents and children under a separate court order and said they will seek to detain families together during their immigration proceedings, though under the Flores agreement immigrant children are generally supposed to be released from custody in about 20 days.

In that case, Justice Department lawyers assured a judge this week that the children in government custody were being well cared for.

FILE - In this June 20, 2018, file photo, immigrant children walk in a line outside the Homestead Temporary Shelter for Unaccompanied Children, a former Job Corps site that now houses them in Homestead, Fla. Immigrant children described hunger, cold and fear in a voluminous court filing about the facilities where they were held in the days after crossing the border. Advocates fanned out across the southwest to interview more than 200 immigrant parents and children about conditions in U.S. holding facilities, detention centers and a youth shelter. The accounts form part of a case over whether the government is complying with a longstanding settlement over the treatment of immigrant youth in custody. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson, File)

Many of the children described conditions in U.S. Customs and Border Protection facilities where they were taken and processed in the initial days after crossing the border. They were identified in the reports solely by their first names.

Timofei, a 15-year-old from Russia who sought asylum at the border with his parents over their beliefs as Jehovah's Witnesses, said night and day blended together in the locked, crowded room where he was held with other boys. It had a single window overlooking an empty corridor, he said. He said there was no soap in the bathroom, and he only sometimes got a single-use toothbrush.

He said he was offered a shower upon arriving at the San Ysidro, California, facility but didn't take one and wasn't allowed one on his second or third day there.

Some children were later sent to the Casa Padre shelter in Texas for immigrant children traveling alone or who were separated from their parents. The facility operates under a contract with the Department of Health and Human Services. There, teenage boys described going hungry and not being given enough time to speak with their parents by phone.

Kenneth Wolfe, a spokesman for HHS's Administration for Children and Families, said the agency wouldn't comment on specific cases but if a contractor doesn't comply with agency procedures, the issue is addressed.

Also in Texas, Keylin, a 16-year-old girl from Honduras, said she traveled north with her mother after her mother's life was threatened back home. The pair turned themselves in at the border near McAllen and were taken to a facility she called the "ice box" because it was so cold.

A day later, they were taken to a facility with caged areas she called the "dog house." There, they were separated and allowed to speak once for 10 minutes over the next four days, she said.

FILE - In this June 18, 2018, file photo, dignitaries take a tour of Southwest Key Programs Casa Padre, a U.S. immigration facility in Brownsville, Texas, where children are detained. Immigrant children described hunger, cold and fear in a voluminous court filing about the facilities where they were held in the days after crossing the border. Advocates fanned out across the southwest to interview more than 200 immigrant parents and children about conditions in U.S. holding facilities, detention centers and a youth shelter. The accounts form part of a case over whether the government is complying with a longstanding settlement over the treatment of immigrant youth in custody. The facility operates under a contract with the Department of Health and Human Services. There, teenage boys described going hungry and not being given enough time to speak with their parents by phone. (Miguel Roberts/The Brownsville Herald via AP, File)

In both places, the food was frozen and smelled bad and she couldn't eat it, she said. She said female guards yelled at her and other girls and made them strip naked and leered at them before they showered.

"I was very frightened and depressed the entire time. I was scared of the guards and scared I would be deported without my mother," she said, adding they were later reunited and sent to a family detention center.

Angel, a 13-year-old who came from Mexico with his mother, said guards told boys in his cell in McAllen, Texas they were going to be adopted and wouldn't see their parents again. He was later sent to family detention with his mother where he said they passed an asylum screening and were awaiting release.

"I am excited to get out of here and get past this nightmare," he said.