WARNING - POTENTIALLY DISTURBING CONTENT After attempting suicide three years ago, 21-year-old Katie Stubblefield became the youngest person in the US to receive a face transplant.

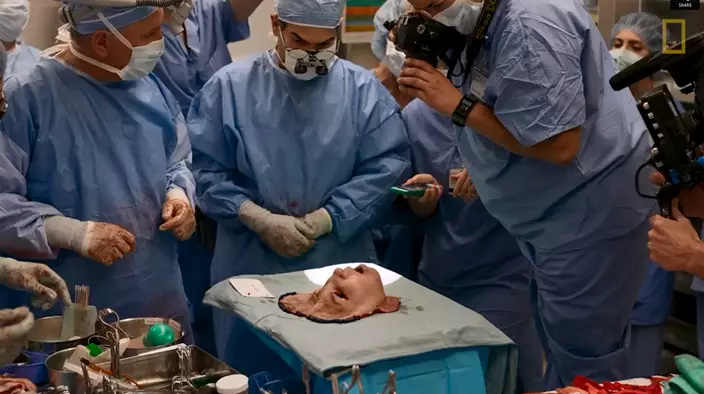

Video screencap

The then-18-year-old Katie faced a number of emotion hurdles, having just found out her boyfriend had been texting another girl and recently having her appendix and gallbladder removed in surgery for gastrointestinal problems, she tried to commit suicide by shooting herself with a .308-caliber hunting rifle in a bathroom of her Mississippi home in March 2014.

Click to Gallery

"I am able to touch my face now, and it feels amazing," said Katie. Her father, Robb, helps to decipher some of her thoughts, as Katie still has some trouble speaking clearly: "You take it for granted, the different components of our faces -- the bone, the tissue, the muscle, everything -- but when it's gone, you recognize the big need. Then when you receive a transplant, you're so thankful."

WARNING - POTENTIALLY DISTURBING CONTENT After attempting suicide three years ago, 21-year-old Katie Stubblefield became the youngest person in the US to receive a face transplant.

The then-18-year-old Katie faced a number of emotion hurdles, having just found out her boyfriend had been texting another girl and recently having her appendix and gallbladder removed in surgery for gastrointestinal problems, she tried to commit suicide by shooting herself with a .308-caliber hunting rifle in a bathroom of her Mississippi home in March 2014.

Katie's older brother, Robert, heard the gunfire found her covered in blood, and recalled, "her face was gone".

“I had never thought of doing that before,” Ms Stubblefield said of her attempt to kill herself. “I felt so guilty that I had put my family through such pain. I felt horrible.”

"I was standing there thinking, 'What do you mean, a face transfer? What do you do?' "

"I had no clue what a face transplant was," Katie said. "When my parents helped explain everything to me, I was very excited to get a face again and to have function again."

Katie waited for a suitable donor for over a year before Andrea Schneider, a 31-year-old organ donor who had recently passed away, was found as a match. Ms Schneider's grandmother, Sandra Bennington, made the decision to donate Andrea's face.

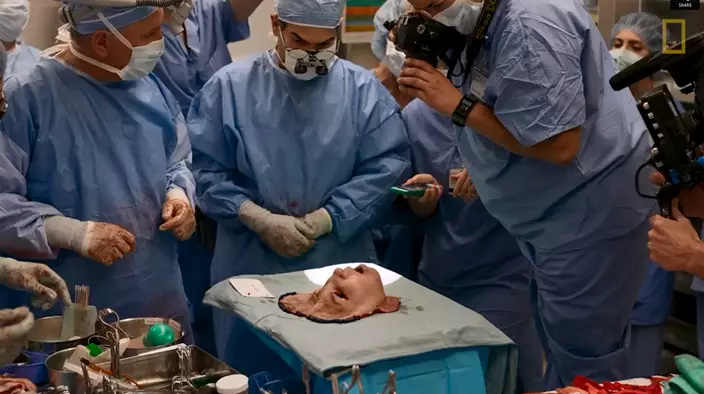

The transplant, which was performed by 11 surgeons in the span of a 31-hour surgery began May 4, 2017, and aimed to restore Stubblefield’s face and functions such as chewing, breathing and swallowing.

"I am able to touch my face now, and it feels amazing," said Katie. Her father, Robb, helps to decipher some of her thoughts, as Katie still has some trouble speaking clearly: "You take it for granted, the different components of our faces -- the bone, the tissue, the muscle, everything -- but when it's gone, you recognize the big need. Then when you receive a transplant, you're so thankful."

Video screencap

Katie's older brother, Robert, heard the gunfire found her covered in blood, and recalled, "her face was gone".

Having been left heavily disfigured in the failed suicide attempt, having lost her forehead, nose, sinuses, mouth except for the corners of her lips and much of the bones that make up the jaws and front of her face. Her eyes remained, but they were askew and badly damaged.

Video screencap

“I had never thought of doing that before,” Ms Stubblefield said of her attempt to kill herself. “I felt so guilty that I had put my family through such pain. I felt horrible.”

"There was an older trauma surgeon who basically told us, 'It's the worst wound that I've ever seen of its kind,' and he said, 'The only thing I can think of that would really give her functional life again is a face transplant,' " Robb Stubblefield, Katie's father, said.

Video screencap

"I was standing there thinking, 'What do you mean, a face transfer? What do you do?' "

Up to that point, none of the family had heard of this medical procedure, which involved transplanting all or parts of the facial tissue, including skin, bone, nerves and blood vessels from a donor cadaver onto the recipient.

Video screencap

"I had no clue what a face transplant was," Katie said. "When my parents helped explain everything to me, I was very excited to get a face again and to have function again."

Video screencap

Katie waited for a suitable donor for over a year before Andrea Schneider, a 31-year-old organ donor who had recently passed away, was found as a match. Ms Schneider's grandmother, Sandra Bennington, made the decision to donate Andrea's face.

Andrea Schneider (Video screencap)

The transplant, which was performed by 11 surgeons in the span of a 31-hour surgery began May 4, 2017, and aimed to restore Stubblefield’s face and functions such as chewing, breathing and swallowing.

Video screencap

"I am able to touch my face now, and it feels amazing," said Katie. Her father, Robb, helps to decipher some of her thoughts, as Katie still has some trouble speaking clearly: "You take it for granted, the different components of our faces -- the bone, the tissue, the muscle, everything -- but when it's gone, you recognize the big need. Then when you receive a transplant, you're so thankful."

Video screencap

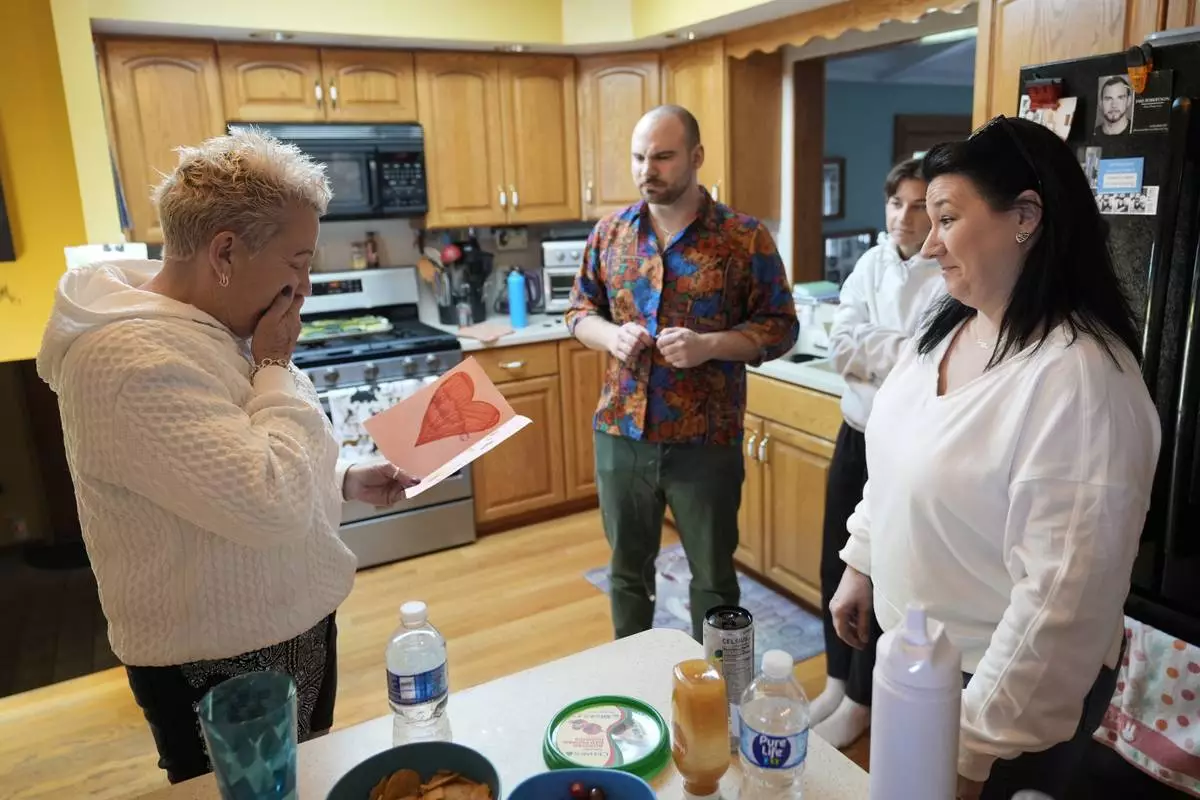

DENVER (AP) — On a brisk day at a restaurant outside Chicago, Deb Robertson sat with her teenage grandson to talk about her death.

She’ll probably miss his high school graduation.

Death doesn't frighten her much. The 65-year-old didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death.

But later, she received a call. A bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their lives with a doctor’s help had made progress.

Then she cried.

“Medical aid in dying is not me choosing to die,” she says she told her 17-year-old grandson. “I am going to die. But it is my way of having a little bit more control over what it looks like in the end.”

That same conversation is happening beside hospital beds and around dinner tables across the country, as Americans who are nearing life’s end negotiate the terms with themselves, their families and, now, state lawmakers.

At least 12 states currently have bills that would legalize physician-assisted death. Eight states and Washington, D.C., already allow it, but only for their own residents. Vermont and Oregon permit any qualifying American to travel to their state for the practice. Patients must be at least 18 years old, within six months of death and be assessed to ensure they are capable of making an informed decision.

Two states have gone in the opposite direction. Kansas has a bill to further criminalize those who help someone with their physician-assisted death. West Virginia is asking voters to enshrine its current ban into the state constitution.

That patchwork of laws has left Americans in most states without recourse. Some patients choose to apply for residency in a state where it’s legal. Others take arduous trips in the late-stage of disease to die in unfamiliar places and beds, far from family, friends and pets.

It was late at night when Rod Azama awoke to his wife crawling on the floor, screaming. Pain from her cancer had punched through the heavy morphine dose.

“Let me die,” screamed his wife, Susan.

As Rod rushed to hold her, the cries faded to repeated mumbles. “Heaven,” she said, again and again.

Susan, 68, pieced through her life’s belongings — family heirlooms, photos, an antique spinning wheel — touching the memories a final time. Then she decided where their next lives would be.

She said goodbye to her constant sidekick, Sunny, a fluffy Maltipoo.

Then the couple traveled to Oregon.

The issue is contentious. Opponents have moral objections with the very concept of someone ending their life. Even with safeguards in place, they argue, the decision could be made for the wrong reasons, including depression or pressure from family burdened by their caretaking.

“It’s normalizing suicide, and it’s incentivizing individuals to end their lives,” said Danielle Pimentel of Americans United for Life. Pimentel raised concerns that pain isn’t the top reason people choose an early departure, adding that policy should focus on bettering end-of-life care.

Two national organizations lobbying for the bills argue it’s about autonomy and compassion, some power over one’s preordained exit.

“It comes down to the right of an individual to control their own end of life decisions free from government intervention or religious interference,” said Goeff Sugerman, national campaign strategist Death with Dignity.

Even though it’s illegal in most states, a 2018 Gallup poll showed more than two-thirds two-thirds of Americans support the practice.

Only a small fraction of Americans across the country, about 8,700, have used physician-assisted death since Oregon became the first state to legalize it in 1997, according to the advocacy group Compassion & Choices.

The organization successfully sued Oregon and Vermont over their residency requirements in the last two years and are using the courts to expand access. California has a bill before lawmakers that would allow out-of-staters to access the procedure. Three states, including Colorado, have proposals to expand in-state access, such as allowing advanced practice registered nurses, not just doctors, to prescribe the medication.

As Robertson discussed the topic with her grandson, he got teary eyed. If it became legal in Illinois tonight, would his grandmother be gone tomorrow? How does it differ from suicides that left empty seats at his school?

Robertson reassured him it would be the very last option as she embarks on new chemotherapy treatment. Then she explained the safeguards.

Typically, two doctors must confirm that a patient has six months to live. The patient must verbally request it twice with a waiting period that varies by state, and submit a written request with witnesses. At three meetings, a physician assesses the patient to ensure they are able to make an informed decision. The patient can be referred to a psychologist for an assessment if there are concerns.

Patients must take the medication themselves. They lose consciousness within a few minutes, and die usually within a few hours.

Eventually the teenager met her eyes. “Granny, I support whatever you choose to do,” he said.

When Gary Drake, a jovial businessman from Florida, received a diagnosis that lung, bone and kidney cancer would end his life within six months, he didn’t deliberate long.

The 78-year-old flew to Oregon in February, after beginning a Facebook post with “RIP.”

“I love you all, say a prayer for me, and I’ll see you on the other side,” the Feb. 13 post read.

His son, Mitch, flew to Oregon to meet with his father. They said their goodbyes, then Drake drank the medicine.

As they played his song request, “Toes” by Zac Brown Band, Drake put the cup down and sang.

“I got my toes in the water, ass in the sand

Not a worry in the world, a cold beer in my hand

Life is good today

Life is good today.”

Then he fell asleep.

Bedayn is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

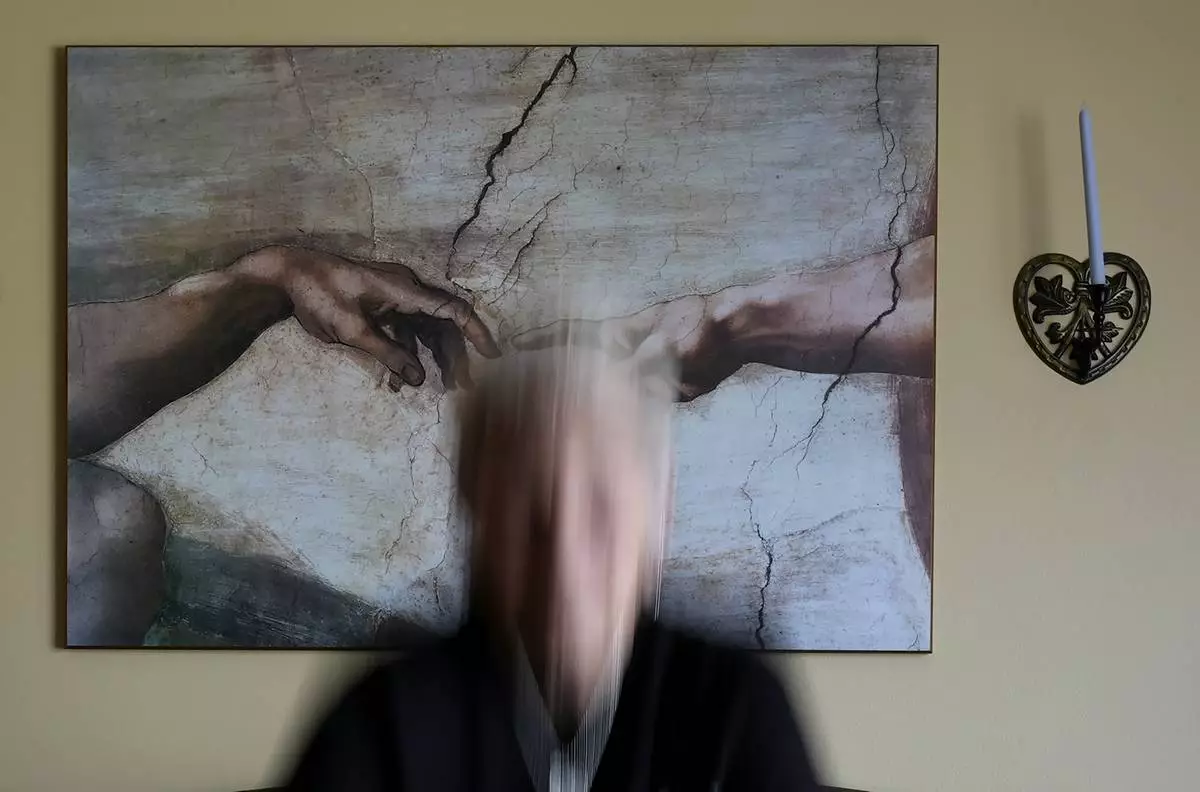

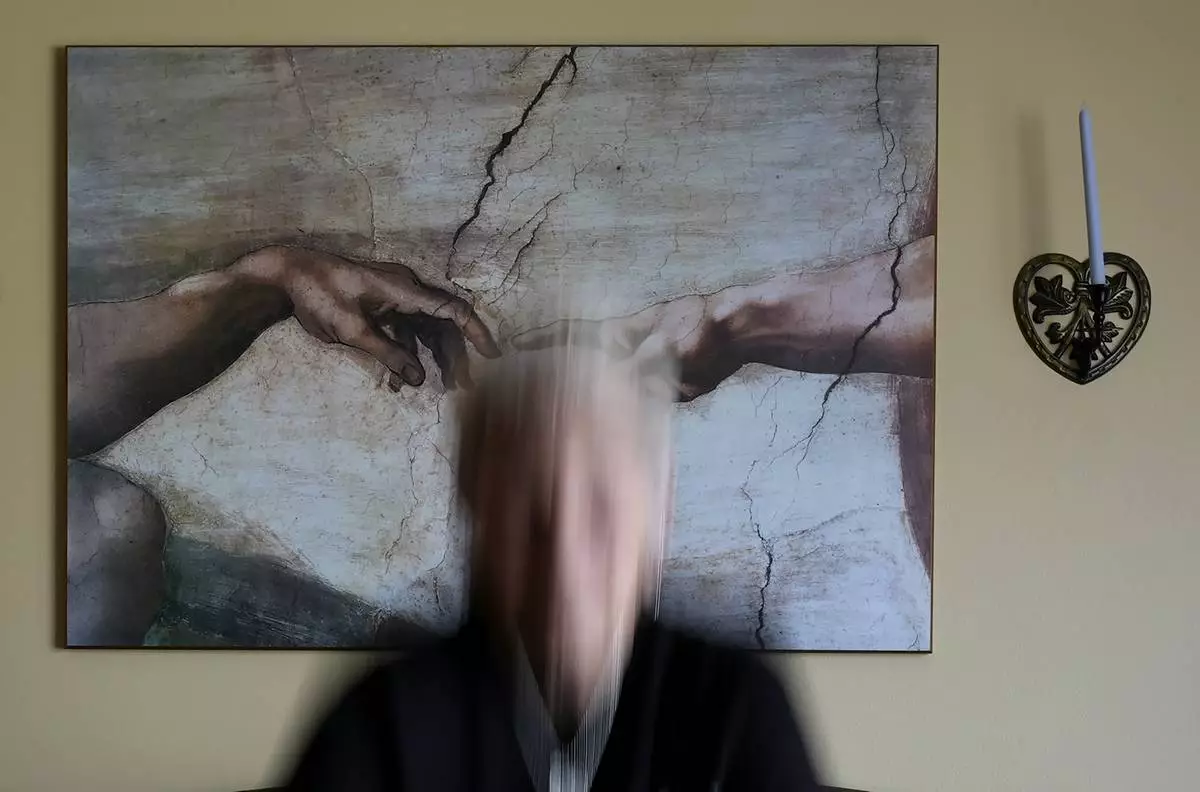

Deb Robertson stands for a portrait in the living room of her Lombard, Ill. home, in front of a reproduction of Creation of Adam painting by Michelangelo, Thursday, March 21, 2024. Robertson didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Deb Robertson kisses her wife Kate Koubek, as they prepare for a meal with family and friends at their Lombard, Ill., home Saturday, March 23, 2024. Robertson didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Deb Robertson sits for a portrait at her Lombard, Ill. home, Thursday, March 21, 2024. She didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Gary Drake and his youngest granddaughter Azalee Drake, 5, pose for a picture on Jan. 4, 2024, in Jacksonville, Fla. Drake's son Mitch Drake flew to Oregon with his father in February, where physician-assisted death is allowed for out-of-state patients who are terminally ill and meet certain requirements. He thanked him for the life he'd given him, and they said their goodbyes. (Courtesy of Mitch Drake via AP)

This undated photo provided by Rod Azama shows Azama with his wife Susan Azama at a party in Md. Eight states and Washington D.C. allow physician-assisted death for certain terminally ill patients, like Susan Azuma, but only for their own residents. Vermont and Oregon permit any qualifying American to travel to their state for the practice, so the Maryland resident traveled to Oregon. (Rod Azama via AP)

This Jan. 28, 2017 photo provided by Rod Azama shows his wife Susan relaxing with her dog Sunny at home in Silver Spring, Md. Eight states and Washington D.C. allow physician-assisted death for certain terminally ill patients, like Susan Azama., but only for their own residents. Vermont and Oregon permit any qualifying American to travel to their state for the practice, so the Maryland resident traveled to Oregon. (Rod Azama via AP)

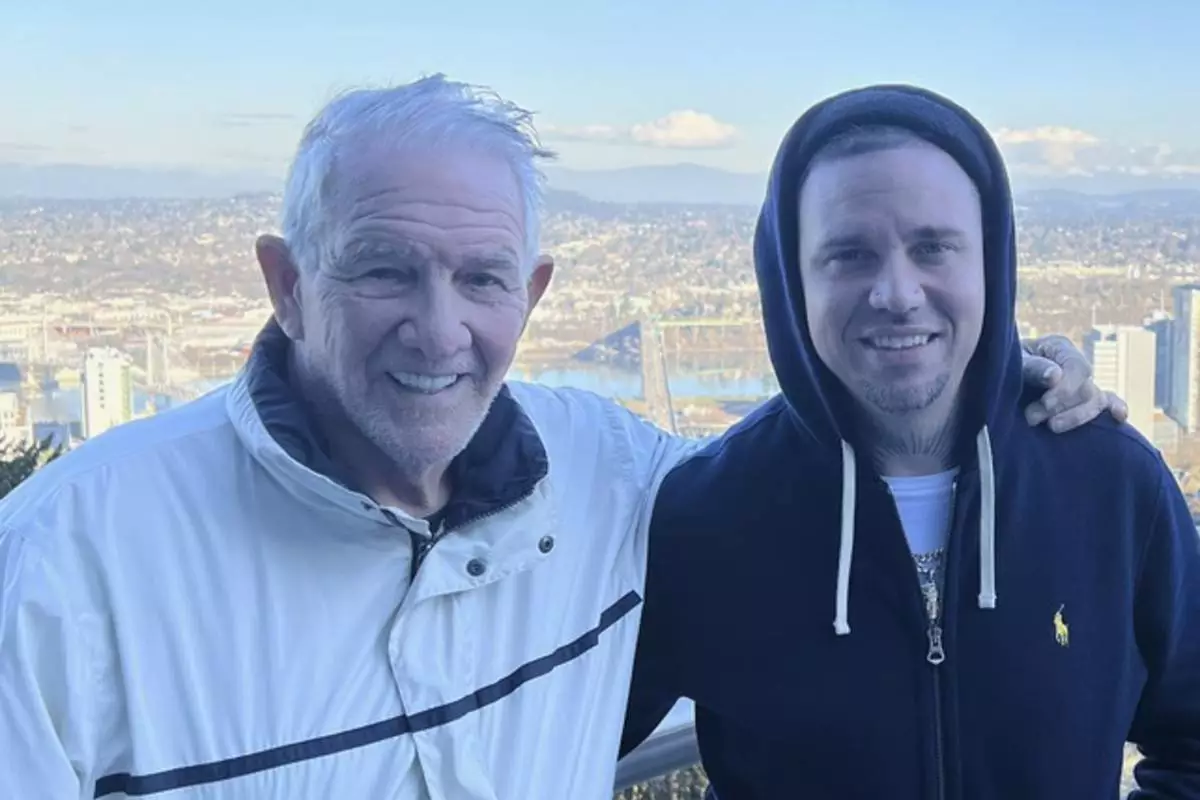

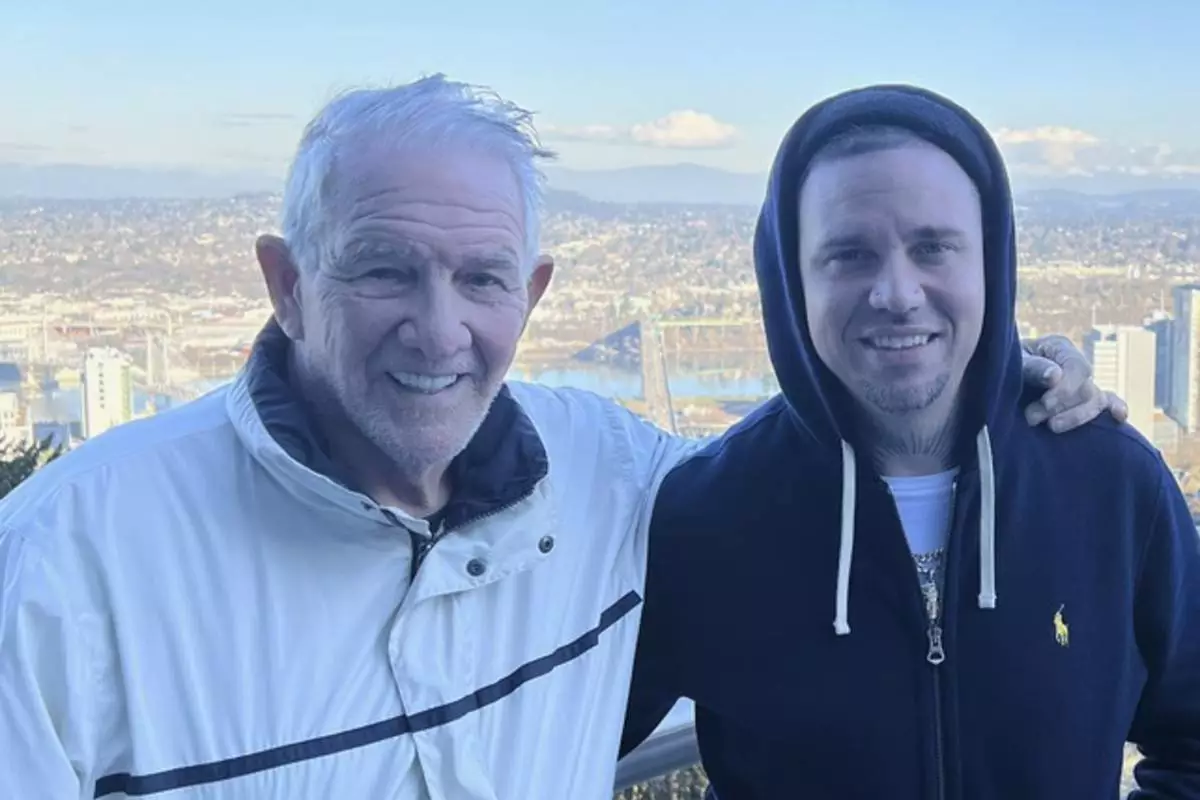

Gary Drake and his son Mitch Drake pose for a picture in Portland, Ore., on Feb. 13, 2024. Mitch Drake flew to Oregon with his father in February, where physician-assisted death is allowed for out-of-state patients who are terminally ill and meet certain requirements. He thanked him for the life he'd given him, and they said their goodbyes. (Courtesy of Mitch Drake via AP)

Gary Drake, left, his son Mitch Drake, and Mitch's mother Cindy Jackson pose for a picture on Jan. 4, 2024, in Jacksonville, Fla. Mitch Drake flew to Oregon with his father in February, where physician-assisted death is allowed for out-of-state patients who are terminally ill and meet certain requirements. He thanked him for the life he'd given him, and they said their goodbyes. (Courtesy of Mitch Drake via AP)

Deb Robertson stands for a portrait in the living room of her Lombard, Ill. home, in front of a reproduction of Creation of Adam painting by Michelangelo, Thursday, March 21, 2024. Robertson didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

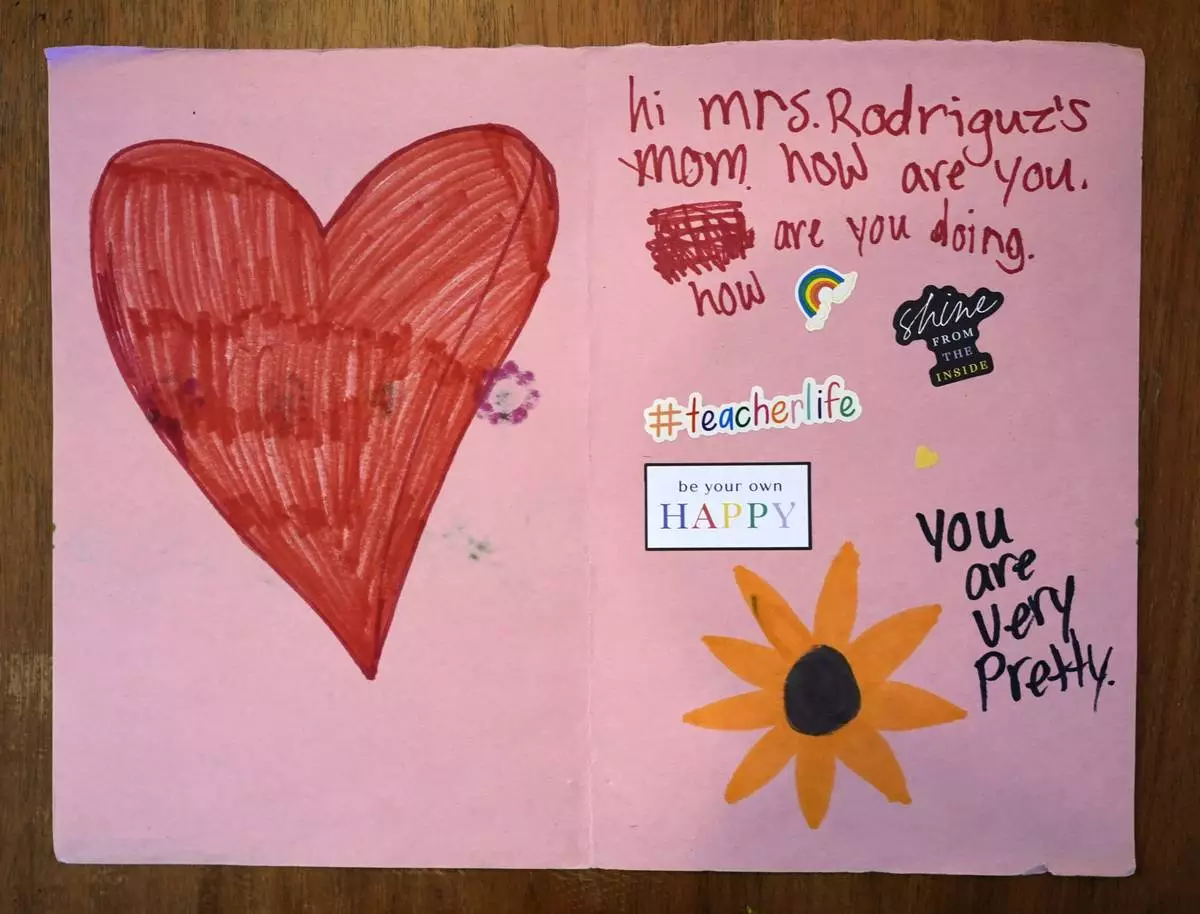

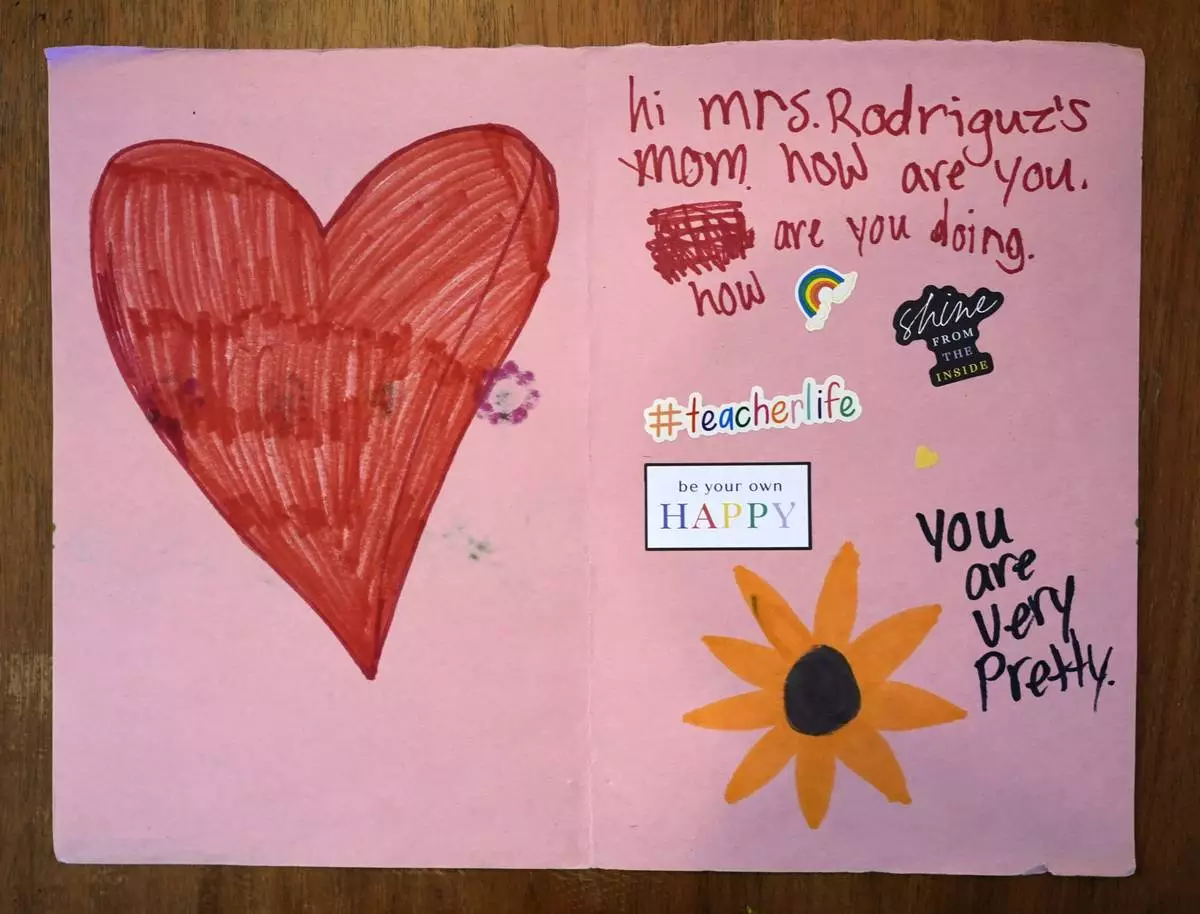

A card made for Deb Robertson by a student of Robertson’s daughter Shannon Rodriguez is seen at Robertson's Lombard, Ill., home Saturday, March 23, 2024. She didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after she received a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

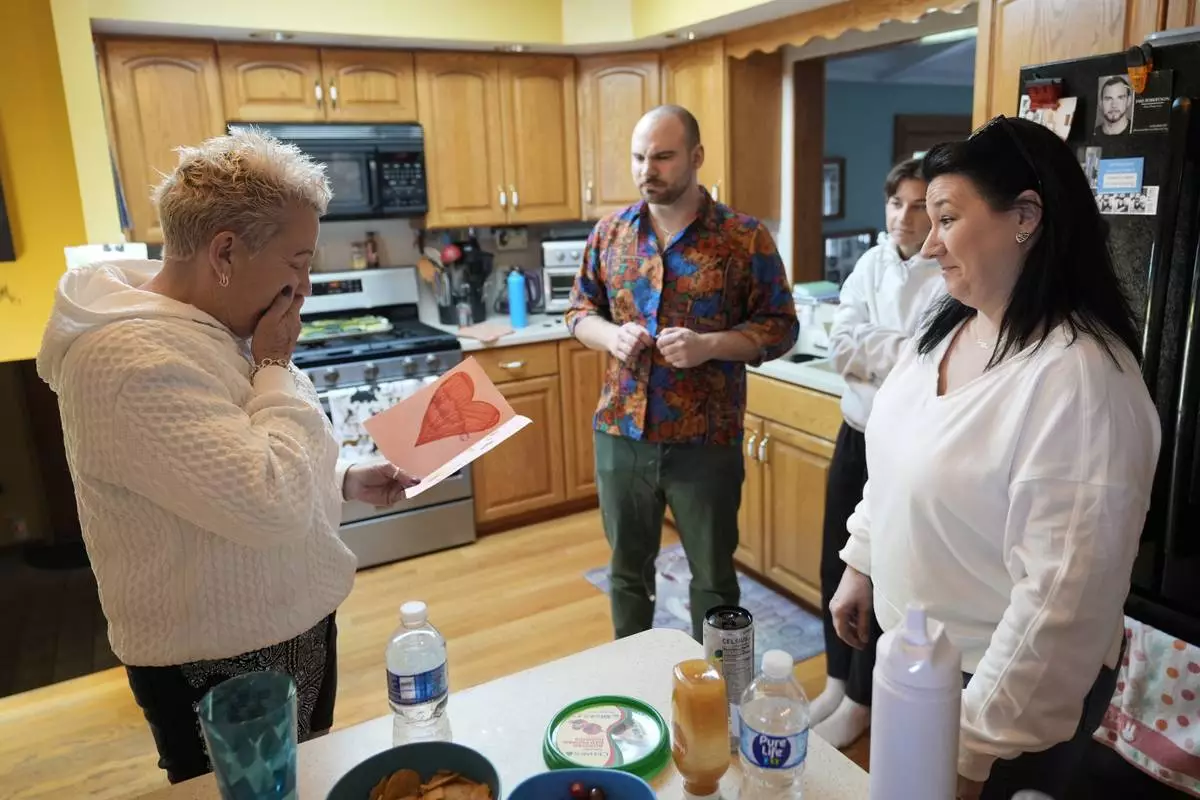

Deb Robertson, left, reacts to a card made for her by a student of her daughter Shannon Rodriguez, right, as her son Jake and niece Emma watch before a BBQ with family and friends at her Lombard, Ill., home Saturday, March 23, 2024. She didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Deb Robertson, right, kisses her wife of over 40 years, Kate Koubek as they prepare for a BBQ with family and friends at their Lombard, Ill., home Saturday, March 23, 2024, in Lombard, Ill. Robertson didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Deb Robertson smiles as she converses with her son Jake before a BBQ with family and friends at her Lombard, Ill., home Saturday, March 23, 2024. She didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Shannon Rodriguez, right, shows off a tattoo made of her mother Deb Robertson's handwriting "Love You More" and sunflower at Robertson's Lombard, Ill., home Saturday, March 23, 2024. Robertson didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Deb Robertson sits with her 12 year-old dog Mazi in the hallway before a meal with family and friends at her Lombard, Ill., home Saturday, March 23, 2024. Robertson didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Deb Robertson shows a collage of her and her wife Kate Koubek at their Lombard, Ill. home, Thursday, March 21, 2024. She didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Deb Robertson kisses her wife Kate Koubek, as they prepare for a meal with family and friends at their Lombard, Ill., home Saturday, March 23, 2024. Robertson didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Deb Robertson looks at a wall crafts with her chemo caps at her Lombard, Ill. home, Thursday, March 21, 2024. She didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

'I'm dying, you're not': Those terminally ill ask more states to legalize physician-assisted death

Deb Robertson sits for a portrait at her Lombard, Ill. home, Thursday, March 21, 2024. She didn’t cry when she learned two months ago that the cancerous tumors in her liver were spreading, portending a tormented death. But later, she cried after receiving a call that a bill moving through the Illinois Legislature to allow certain terminally ill patients to end their own lives with a doctor’s help had made progress. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

'I'm dying, you're not': Those terminally ill ask more states to legalize physician-assisted death