Anita was told she’d beaten aggressive cancer before her husband Simon got the kidney transplant he’d waited eight years for weeks later.

A mum who fought aggressive breast cancer as her husband waited desperately for a new kidney has told of her joy at being given the all-clear – just weeks before he underwent a lifesaving transplant.

Click to Gallery

Anita was told she’d beaten aggressive cancer before her husband Simon got the kidney transplant he’d waited eight years for weeks later.

Anita Howell, 44, was forced to tell her children Sarah, 11, and James, six – who’d grown up watching their dad Simon, also 44, battle renal failure – that she, too, was poorly when she was diagnosed with cancer in December 2016.

Then, on 9 August, Simon, a retired pathology doctor, finally received the call he’d waited eight years for, and has just undergone a kidney transplant.

“I know people don’t like to think about death, but you don’t need your organs after you’re gone, and by donating them, not only do you a save a life, but you transform an entire family.”

Anita explained: “When we met, we knew kidney problems were on the cards, but we thought it would be much later in life – that we would have the 2.4 children and he would be a consultant by then and everything would be different.”

She willingly donated her organ and, following a transplant in May 2005, the operation appeared to have been a success.

By 2010, Simon was in the end stages of kidney failure again. Forced to medically retire, he spent four hours a day connected to a dialysis machine – first at hospital before he was eventually able to do it at home – whilst he waited for an organ to become available on the transplant list.

Anita said: “We had to sit the children down and tell them that Mummy has cancer. We said it was okay to be angry and sad, but that life would go on, so it was okay to still have fun too.

Meanwhile, Simon was still on dialysis as he waited for a transplant.

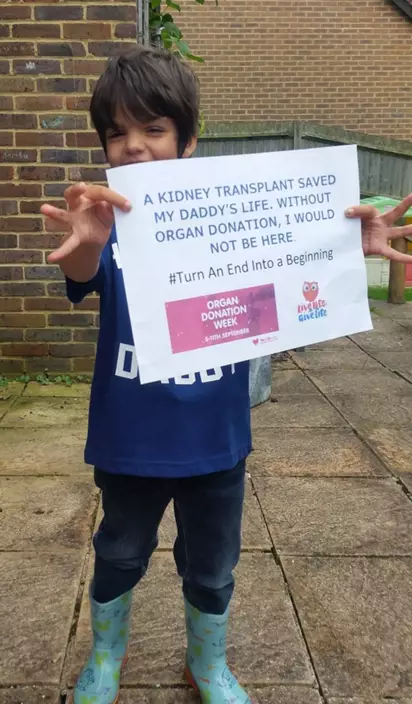

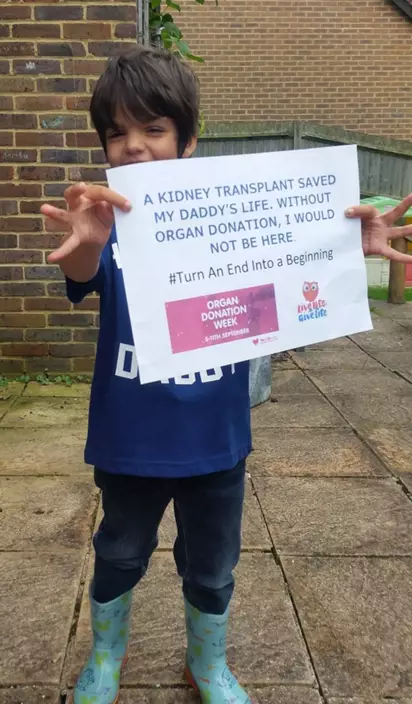

James promoting Organ Donation Week (PA Real Life/Collect)

Anita Howell, 44, was forced to tell her children Sarah, 11, and James, six – who’d grown up watching their dad Simon, also 44, battle renal failure – that she, too, was poorly when she was diagnosed with cancer in December 2016.

As she underwent gruelling treatment, her ailing husband’s condition deteriorated – prompting their daughter to ask whether Daddy would live long enough to walk her down the aisle one day.

But, in June this year, Anita, a supermarket worker, of Burgess Hill, West Sussex, was relieved to be told that there were no traces of cancer left in her body.

The family on a day out in February 2015 (PA Real Life/Collect)

Then, on 9 August, Simon, a retired pathology doctor, finally received the call he’d waited eight years for, and has just undergone a kidney transplant.

Now speaking out ahead of Organ Donation Week 2018, which runs from 3 to 9 September, Anita said: “Even now, this doesn’t feel real. We’ve gone from expecting that Simon wouldn’t be around to see the kids reach adulthood to having a very real chance of him living to see his grandchildren born, thanks to organ donation.”

She added: “Six thousand people across the UK are in need of a transplant right now, and around three a day die waiting.

Simon and Sarah in late 2009 (PA Real Life/Collect)

“I know people don’t like to think about death, but you don’t need your organs after you’re gone, and by donating them, not only do you a save a life, but you transform an entire family.”

When Anita and Simon first met in 1995 as students in north London, they knew his kidneys were likely to start failing in the future.

He’d been born with renal dysplasia, a condition where the internal structures of the organs do not develop properly in the womb.

But, the pair didn’t expect any complications to occur until he was in his 50s or 60s.

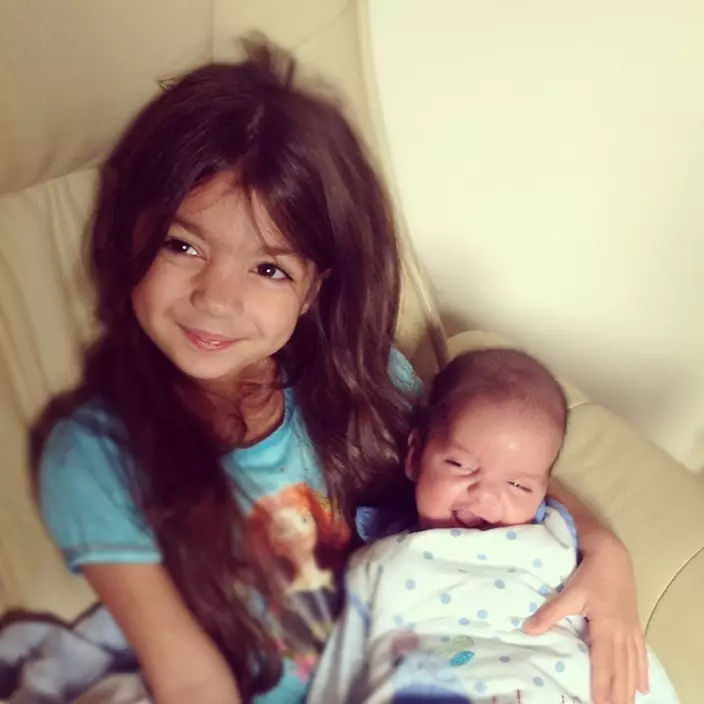

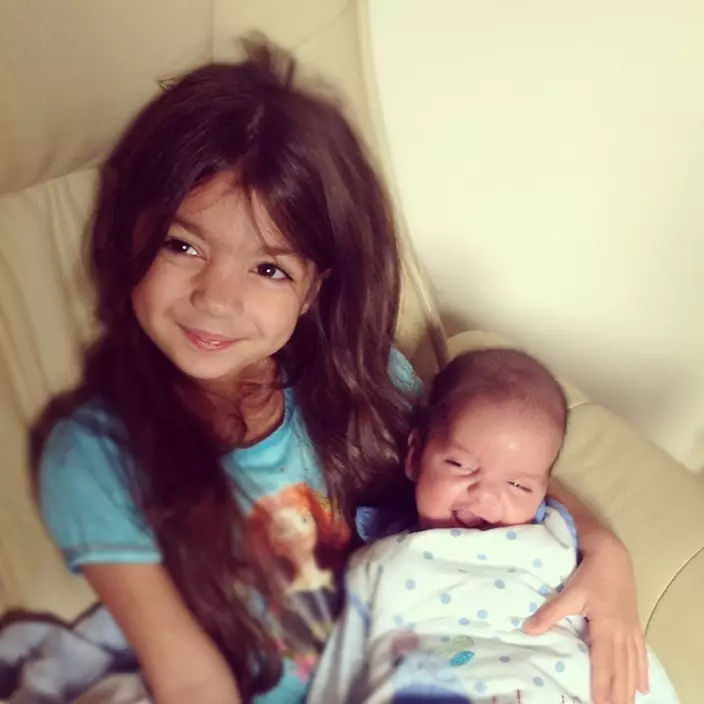

Sarah holding her brother James, just weeks old, in September 2012 (PA Real Life/Collect)

Anita explained: “When we met, we knew kidney problems were on the cards, but we thought it would be much later in life – that we would have the 2.4 children and he would be a consultant by then and everything would be different.”

But, as he turned 29 in 2004, Simon fell ill – and was shocked when blood tests revealed he was in the end stages of kidney failure.

Right away, medics began searching for a donor and were thrilled when his mum Linda was a found to be a match.

Anita and Simon with their children in August 2016 (PA Real Life/Collect)

She willingly donated her organ and, following a transplant in May 2005, the operation appeared to have been a success.

Simon returned to work and, in 2006, Anita discovered she was pregnant with Sarah, who was then born in February 2007.

But two years later, Simon’s health declined once again, and it emerged his transplant had failed.

Anita and other family members were tested to see if they were a potential match but unfortunately, they were the wrong blood type.

Simon the day after his first transplant at Guy's and St. Thomas' Hospital in London in May 2005 (PA Real Life/Collect)

By 2010, Simon was in the end stages of kidney failure again. Forced to medically retire, he spent four hours a day connected to a dialysis machine – first at hospital before he was eventually able to do it at home – whilst he waited for an organ to become available on the transplant list.

Towards the end of 2011, the couple were overjoyed when Anita unexpectedly fell pregnant with James, who was born in August 2012.

With Simon’s health continuing to deteriorate though, the birth posed heartbreaking questions about how much of his children’s lives he’d be around to see.

Then, in December 2016, the family were dealt another bombshell when a lump Anita found under her right armpit turned out to be grade three locally aggressive breast cancer.

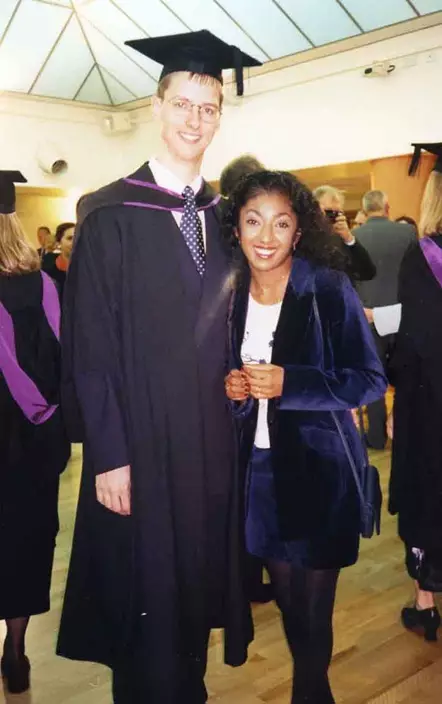

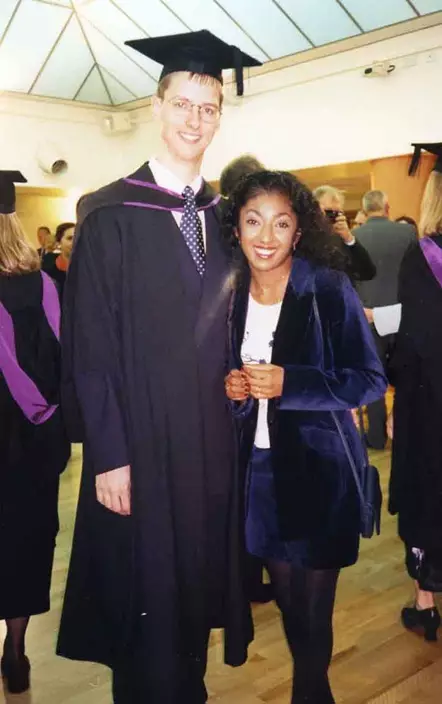

Anita and Simon at his graduation from medical school in July 1998 (PA Real Life/Collect)

Anita said: “We had to sit the children down and tell them that Mummy has cancer. We said it was okay to be angry and sad, but that life would go on, so it was okay to still have fun too.

“It was so difficult for them, knowing that we were both sick. It was rare to have a day where we both felt well enough to do something as a family.”

As 2017 began, Anita, who was too ill to work throughout her treatment, started intensive chemotherapy, undergoing six rounds in total.

Her immune system wiped out, she was repeatedly hospitalised with infections – even contracting sepsis twice.

Anita and Simon on their wedding day - the day after his graduation - on 4 July 1998 (PA Real Life/Collect)

Meanwhile, Simon was still on dialysis as he waited for a transplant.

“We were both under the care of the Royal Sussex in Brighton, so sometimes we’d be in treatment on the same day,” she recalled. “We’d drive down together, then I’d drop Simon off for his dialysis and he’d then come to collect me as I finished chemotherapy.

“All throughout my treatment, I never really had a good day. I was so exhausted. Even when it was just Simon ill, we were limited to what we could do, but now I was too, maintaining that normality was virtually impossible.

“We had to rely a lot on help from family and friends, so we felt it was important to be open with the children about what was happening.”

In May 2017, Anita finished chemotherapy, before undergoing a double lumpectomy – where the cancer and some surrounding tissue is cut away – and having 11 lymph nodes removed at Princess Royal Hospital, Haywards Heath, East Sussex.

Then, in August, she started radiotherapy, having a total of 20 sessions before beginning a course of Tamoxifen, a hormonal therapy drug she’ll need to take for the next 10 years.

Thankfully, in June 2018, a mammogram showed she was officially classed as NED – ‘no evidence of disease’.

Simon the morning after his transplant in August 2018 (PA Real Life/Collect)

“I can’t describe the utter relief I felt to hear those words,” she said. “As a scan approaches, you can feel really anxious so hearing the cancer hadn’t returned was an enormous weight off.”

But the family’s ordeal wasn’t over yet. Ending up in hospital with a serious infection the following month, Simon’s prognosis did not seem as positive.

That was, until the night of August 9, when a life-changing call came.

Anita recalled: “We were sat on the sofa when the phone rang, and Simon answered. I couldn’t work out what was going on, but I could tell something big had happened.

“Then Simon hung up and said, ‘I think I have a kidney.’

“It just didn’t feel real. A friend took him to Guy’s Hospital in London, while I stayed behind for the night to organise the kids.”

She continued: “The next morning, I was going about all these everyday tasks, like dropping them at their grandparents and sorting everything for a drama show Sarah had.

“It was all so normal – but in the back of my mind, I kept thinking, ‘Simon is in hospital right now finding out if he has a kidney.’”

Incredibly, the organ was found to be a match, and on the evening of August 10, Simon underwent his operation.

Coming to visit, Anita was amazed at how much healthier he already looked.

“He seemed so much brighter and more alert,” she said.

“All we know about his donor was that they were a similar age to Simon, but we hope to one day write to their family to thank them for all they’ve done.”

Now, though he is still recovering, Simon is hopeful that the transplant has been successful.

Having had to break so much difficult news to their young children, the couple have written a series of children’s books about their experiences to provide a learning tool for parents going through similar trauma.

Called Meet Lucy and Jack, the series has three titles so far – H is for Haemodialysis, P is for Peritoneal Dialysis and K is for Kidney Transplant.

After raising money via a crowdfunding site to get it published, Anita has just announced a fourth called B is for Breast Cancer, which will be available on Amazon.

They also hope their story will inspire people to sign up as organ donors, sharing their wishes with loved ones.

Simon said: “Even now, this feels utterly unreal after eight years of waiting. It’s like the best present you received at Christmas as a child – only infinitely better. I’ve gone from wondering if I’ll see the children reach secondary school to being able to give Sarah away when she gets married.”

He continued: “It’s hard to grasp how amazing a thing donating organs is. You lose nothing by doing it, but six or seven people gain the world.”

Anthony Clarkson, Interim Director of Organ Donation and Transplantation for NHS Blood and Transplant, said: “This is brilliant news for a family who have been through so much and done so much to promote the lifesaving power of organ donation.

“Simon’s transplant was made possible through the generosity of a family who supported donation at a time of grief and I hope it will bring them comfort. I’m sure Simon’s story will inspire more families to say yes to organ donation, saving many more lives.”

Register as an organ donor at www.organdonation.nhs.uk

DES MOINES, Iowa (AP) — Stung by paying billions of dollars for settlements and trials, chemical giant Bayer has been lobbying lawmakers in three states to pass bills providing it a legal shield from lawsuits that claim its popular weedkiller Roundup causes cancer.

Nearly identical bills introduced in Iowa, Missouri and Idaho this year — with wording supplied by Bayer — would protect pesticide companies from claims they failed to warn that their product causes cancer, if their labels otherwise complied with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s regulations.

But legal experts warn the legislation could have broader consequences — extending to any product liability claim or, in Iowa’s case, providing immunity from lawsuits of any kind. Critics say it could spread nationwide.

"It’s just not good government to give a company immunity for things that they’re not telling their consumers,” said Matt Clement, a Jefferson City, Missouri, attorney who represents people suing Bayer. “If they’re successful in getting this passed in Missouri, I think they’ll be trying to do this all over the country.”

Bayer described the legislation as one strategy to address the “headwinds” it faces. About 167,000 legal claims against Bayer assert Roundup causes a cancer called non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which Bayer disputes. The company has won some cases, settled many others but also has suffered several losses in which juries awarded huge initial judgments. It has paid about $10 billion while thousands of claims linger in court.

Though some studies associate Roundup's key ingredient with cancer, the EPA has regularly concluded it is not likely to be carcinogenic to humans when used as directed.

The costs of “defending a safe, approved product” are unsustainable, said Jess Christiansen, head of communications for Bayer's crop science division.

The legislation was introduced in targeted states pivotal to Bayer's Roundup operations and is at a different stage in each. It passed the Iowa Senate, is awaiting debate in the Missouri House and was defeated in Idaho, where this year's legislative session ended.

Farmers overwhelmingly rely on Roundup, which was introduced 50 years ago as a more efficient way to control weeds and reduce tilling and soil erosion. For crops like corn, soybeans and cotton, it’s designed to work with genetically modified seeds that resist Roundup’s deadly effect.

Missouri state Rep. Dane Diehl, a farmer who worked with Bayer to sponsor the legislation, cited concerns that costly lawsuits could force Bayer to pull Roundup from the U.S. market, leaving farmers to depend on alternative chemicals from China.

“This product, ultimately, is a tool that we need," said Diehl, a Republican.

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds, a Republican, said in an email the legislation maintains the integrity of the regulatory process and, without it, “Iowa risks losing hundreds of jobs” in Muscatine, an eastern Iowa city where Roundup is mostly produced.

The Associated Press is seeking public records on Bayer’s communications with governor's offices in Iowa, Missouri and Idaho.

Bayer, like other companies, hires lobbyists in states to advocate for its interests. The company backs this legislation in the states where “we have a big, direct economic impact,” Christiansen said.

Roundup’s key ingredient, glyphosate, is derived from phosphate mined in Idaho. And St. Louis is the headquarters of its North America crop science division, acquired in its 2018 purchase of Monsanto. Because of that, many of the lawsuits are filed in Missouri.

The five lobbyists registered for Bayer in Iowa and three in Idaho is largely consistent with recent years, but the number working in Missouri this year ballooned from four to nine. Lobbyist expenditures exceeded $8,000 in Idaho this year; similar information was not available in Iowa or Missouri.

Led by Bayer, a coalition of agricultural organizations called Modern Ag Alliance also is spending tens of thousands of dollars on radio and print advertisements claiming that trial lawyers and litigation threaten the availability of glyphosate.

On its website, the group asserts that at risk are 500 jobs connected to glyphosate production in Iowa, and 800 jobs in Idaho.

Bayer stopped short of threatening closures. The Iowa facilities, including in Muscatine, “are very critical facilities to our business, so we'll remain at some sort of support level,” Christiansen said.

At issue in the lawsuits and legislation is how Bayer – and any other pesticide company — communicates with consumers about the safety of its products.

Companies are required to register products with the EPA, which evaluates — and then reevaluates every 15 years — a pesticide and its label. The EPA reiterated in 2020 that glyphosate used as directed posed no health risks to humans. But a federal appeals court panel in 2022 ruled that decision “was not supported by substantial evidence” and ordered the EPA to review further.

The debate over glyphosate escalated when a 2015 report by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, part of the World Health Organization, said it's “probably carcinogenic to humans" based on “limited” evidence of cancer in people and “sufficient” evidence in study animals.

Based on that international report, California sought to add a cancer warning label to products containing glyphosate. But a federal appeals court ruled against California last November, concluding such a warning wasn't factual.

Christiansen emphasized that many regulatory agencies worldwide agree with the EPA and insisted Bayer has to stick to EPA labeling to ensure it isn't providing false or misleading information. She added that the company is transparent in the information it does provide.

Critics of the legislation aren't convinced, citing examples such as opioids and asbestos that had been deemed safe for use as directed — until they weren't.

There also are concerns that the legislation could stifle any product liability claim since most rely on the argument that a company failed to warn, said Andrew Mertens, executive director of the Iowa Association for Justice, an organization for trial lawyers.

Jonathan Cardi, a product liability and torts expert at Wake Forest University School of Law, also said a strict reading of the Iowa legislation extends beyond liability claims, and “the way it’s drafted makes it interpretable to mean nobody could bring any suit.”

In lobbying lawmakers and in speaking with the AP, Bayer representatives disputed that the legislation would cut off other legal actions. Several legal experts said the legislation is unlikely to affect the 18,000 lawsuits already pending in Missouri’s capital of Jefferson City, and wouldn’t prevent claims in states that don’t adopt similar legislation.

In Idaho, the Republican-led Senate narrowly defeated the bill amid concerns about relying on federal agencies' safety standards and limiting the ability of harmed individuals to sue.

John Gilbert, who farms in Iowa Falls, Iowa, with limited use of Roundup, called Republicans hypocritical for attempting to protect corporate interests after campaigning on standing up for Iowans.

The bill “invites a lot of reckless disregard," said Gilbert, who is on the board for the Iowa Farmers Union. “No amount of perfume’s gonna make it anything but a skunk."

Lieb reported from Jefferson City, Missouri.

FILE - Soybeans are seen in a field on a farm, Friday, Sept. 2, 2016, in Iowa. The maker of a popular weedkiller is turning to lawmakers in key states to try to squelch legal claims that it failed to warn about cancer risks. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall, File)

FILE - The Bayer AG corporate logo is displayed on a building of the German drug and chemicals company in Berlin, Monday, May 23, 2016. Bayer, the maker of a popular weedkiller, is turning to lawmakers in key states to try to squelch legal claims that it failed to warn about cancer risks. Bayer disputes such claims but already has paid about $10 billion to resolve them. (AP Photo/Markus Schreiber, File)

FILE - Phosphate ore is dug up and transported from Monsanto Company's South Rasmussen Mine site near Soda Springs, Idaho, July 16, 2009. Bayer acquired Monsanto in 2018. Bayer, the maker of a popular weedkiller, is turning to lawmakers in key states to try to squelch legal claims that it failed to warn about cancer risks. The company disputes such claims. A key ingredient of the weedkiller, glyphosate, is derived from phosphate mined in Idaho. (Bill Schaefer/The Idaho State Journal via AP, File)

FILE - Containers of Roundup are displayed on a store shelf in San Francisco, Feb. 24, 2019. Thousands of legal claims against drug and chemicals company Bayer assert Roundup causes a cancer called non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which Bayer disputes. (AP Photo/Haven Daley, File)

FILE - A soybean field is sprayed in Iowa, July 11, 2013. The maker of a popular weedkiller is turning to lawmakers in key states to try to squelch legal claims that it failed to warn about cancer risks. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall, File)