WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT Therapist Ariane believes the vampire-style feeds could even extend his lifespan.

A therapist who bonds with his three giant pet leeches by letting them suck his blood once a month, claims the vampire-style feeding sessions have improved his health and could even extend his lifespan.

Click to Gallery

Ariane and one of his pet snakes (Collect/PA Real Life)

Ariane bonds with his pet leeches by letting them suck his blood (Collect/PA Real Life)

Warning graphic image: Ariane bonds with his pet leeches by letting them suck his blood (Collect/PA Real Life)

Leeches on Ariane's face (Collect/PA Real Life)

The leeches roam freely around Ariane's bedroom at his family home (Collect/PA Real Life)

Ariane also has eight-foot anaconda snakes (Collect/PA Real Life)

One of Ariane's anaconda snakes (Collect/PA Real Life)

Ariane with his snakes at home (Collect/PA Real Life)

Ariane and one of his pet snakes (Collect/PA Real Life)

Placing the three predatory worms he calls his “children” on his left arm, Ariane Khomjani, 22, watches them grow up to 15 inches long, as they gorge on his blood – knowing they are capable of drinking 10 times their own body weight.

Letting them out of their aquarium, to roam freely around his bedroom at his family home in Walnut Creek, California, USA, when he is home, Ariane regularly strokes the pets, which he adores, saying: “People are only scared of what they don’t understand.”

He continued: “In fact, there are so many medicinal uses to leech feeding that we in the West are now only starting to realise.

Ariane bonds with his pet leeches by letting them suck his blood (Collect/PA Real Life)

“Having leeches suck your blood can help with circulation, arthritis, complexion and even extend your lifespan.

“I play a lot of tennis and if ever I have any soreness in my arms, I put a leech on and the pain goes away – it’s incredible.”

Calling his Asian buffalo leeches – native to the swamps of southern India – Laera, Liidra and Lykra, they are the latest proud addition to Ariane’s exotic pet collection, which includes four eight-foot anaconda snakes and a carnivorous Galapagos centipede called Cax.

Warning graphic image: Ariane bonds with his pet leeches by letting them suck his blood (Collect/PA Real Life)

His taste for slithery companions also brought him human love, after his student girlfriend Mackenzie Lynn, 18, spotted his snake and leech-themed Instagram page and got in touch.

Speaking fondly of Mackenzie, who shares his fascination for tropical creatures, he continued: “It’s really cool to meet a girl who is as into reptiles as I am – you really don’t meet many girls who are like that.”

Leeches on Ariane's face (Collect/PA Real Life)

Keen to dispel negative perceptions of slippery animals, Ariane insists his peculiar pets regard him as a parent.

He continued: “People often say to me that keeping these sorts of pets is dangerous, that I should watch out because one day the snakes might start sizing me up, or the leeches might bleed me dry.

“But, once they become comfortable with you, they’re not dangerous at all. I’ve raised them all since they were small enough to wrap around my little finger and they mean a lot to me, like they are my kids.”

The leeches roam freely around Ariane's bedroom at his family home (Collect/PA Real Life)

Keeping various smaller reptiles and insects, like snakes, scorpions and lizards at his parents’ house throughout his teens, they were delighted that he took such an avid interest in zoology.

As a youngster, Ariane even went to educational sideshows around his home state, where collectors would show off their pets.

He said: “One time, at one of these shows, I met a guy who had an anaconda. It was the first time I had seen one and I thought it was amazing, so I started researching them and from then on dreamed about having one of my own.”

Gaining experience with smaller bull snakes, Ariane’s dreams were realised when, aged 17, he bought his first yellow anaconda, Annie, for $300 (£230) later acquiring three more, Allie, Amy and Ana.

Ariane also has eight-foot anaconda snakes (Collect/PA Real Life)

But the collector’s thirst for the exotic creatures was not entirely quenched until he bought his giant leeches.

After seeing a YouTube video of a giant buffalo leech sucking a man’s blood, it became his mission to own some.

“I saw this thing and thought, ‘Can that be real? And if it is, I want one!'” he said.

Buying three baby leeches from a dealer in Holland for $60 (£45) dollars each, Ariane soon began feeding them with his own blood, to make them grow as fast as possible.

“I’ve tried all sorts of places on my legs and arms,” said Ariane, who feeds his snakes with frozen rats, which he buys in bulk.

He added: “Now I usually just do my left arm, because they’ve got used to feeding there.

“The initial bite, when they are attaching themselves to you, can hurt. It feels a bit like thousands of tiny needles pricking your skin. But once they’re on, it feels fine and there’s a very relieving sensation to it.”

One of Ariane's anaconda snakes (Collect/PA Real Life)

Ariane typically allows his leeches to suck up a pint of his blood – roughly a tenth of the amount held within an average person’s body – at each mealtime.

As they feed, he watched them inflate like water balloons, growing by up to 15 inches, when they are full.

Singing their virtues as the “perfect pets,” he said: “Having a snake or a leech is not like having a dog or a cat because they don’t actively seek your affection.”

Ariane with his snakes at home (Collect/PA Real Life)

He added: “But I’m at a stage with them now where they feel completely happy with me being around them and don’t feel threatened by me. That’s the highest form of respect you can have from them. “Some people might think it’s weird keeping these sorts of pets, because they think of them as scary or creepy.

“But I always say to them, ‘Before you get scared by animals, find out what they’re really about – and you never know, you might like them.'”

MEXICO CITY (AP) — The almighty eagle perched on a cactus while devouring a serpent on Mexico’s flag hints at the myth behind the foundation of the country’s capital.

It's a divine sign in an ancient legend, according to which the god Huitzilopochtli asked a group called the Mexica to leave their homeland in search of a place to establish a new city.

It took some 175 years before they spotted the sacred omen and established the city of Tenochtitlan in 1325 where Mexico City stands today.

How the eagle, the cactus and the serpent became an emblem and endured through the European conquest is the focus of a new exhibition. “A coat of arms, an emblem, a symbol of identity,” runs through Dec. 15 at the Old City Hall in downtown Mexico City.

The exhibit is among the government’s activities marking the 700th anniversary of the founding of the Mexica capital.

“Recognizing Tenochtitlan doesn’t mean recalling a dead past, but rather the living heartbeat that still beats beneath our city,” President Claudia Sheinbaum said during an official ceremony in July. “It was the center of an Indigenous world that built its own model of civilization — one in harmony with the Earth, the stars, and its gods and goddesses.”

Fragments of that civilization lie underneath the Old City Hall, the current seat of Mexico City’s government.

Built by order of Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés in 1522, its construction used stones from ancient Mexica sacred sites. The building has been renewed over time, but its halls have witnessed centuries of governance and symbolism.

“Holding the exhibition in this City Hall, a place of decisions and memory, is a way to recognize the history of those who once inhabited it and how its transformations still echo in Mexico City’s identity,” said Mariana Gómez Godoy, Director of Mexico City’s Cultural Heritage, during the exhibit’s inauguration in November.

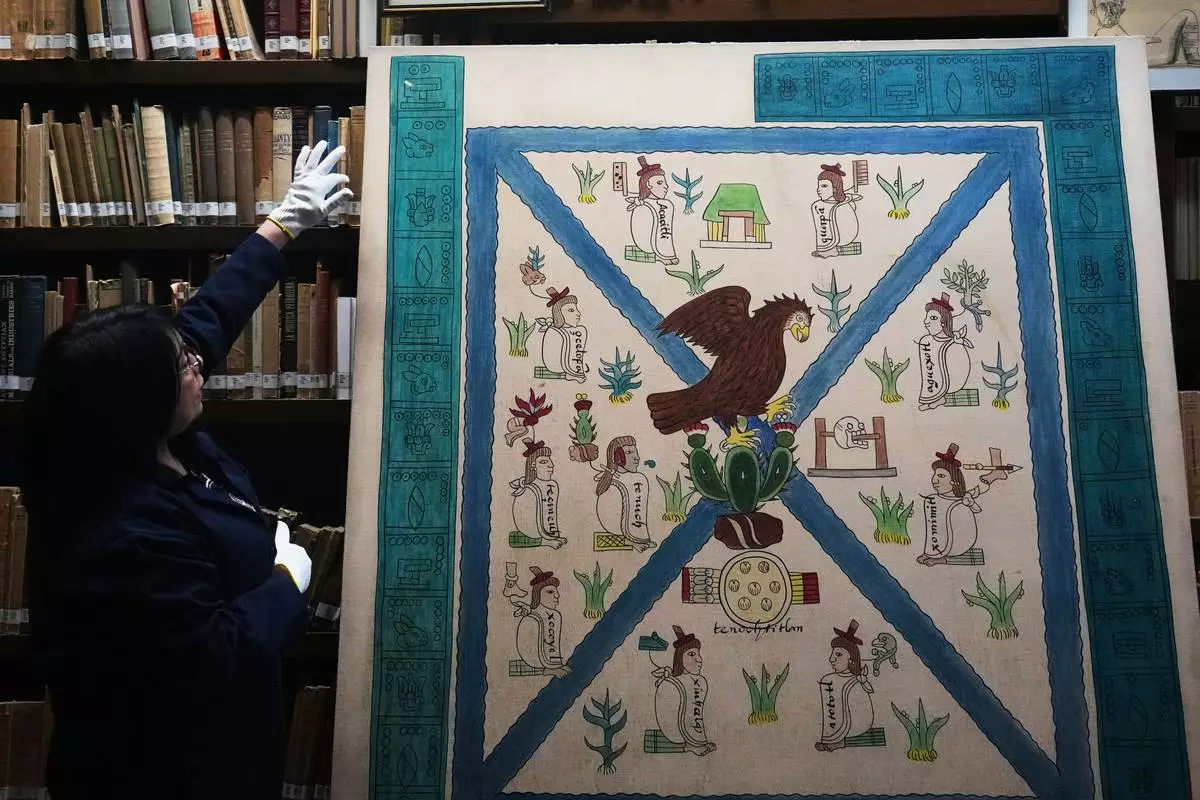

The Mexica themselves recounted their story after Tenochtitlan fell to the Europeans. Several codices — including some produced after the conquest — depict the path that led them to fulfill their deity’s task.

According to the Templo Mayor Museum, the region’s pre-Hispanic people preserved the origin story of a long journey that led to the founding of Tenochtitlan as a cornerstone of their traditions.

They identified a small island in Lake Texcoco —now central Mexico City— as the place where the Mexica saw the eagle foretold by Huitzilopochtli.

Some scholars, however, revisit the narrative with a different lens. Eduardo Matos Moctezuma — an acclaimed archaeologist from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History — has argued that the legend is a symbolic retelling of historical events, rather than a literal claim about divine prophecy.

The new exhibit offers a historical overview of how the image evolved — from its establishment as the city’s coat of arms in 1523 under Emperor Charles V to its transformation into an emblem of Mexico as an independent nation.

Curated by researcher Guadalupe Lozada, it also displays images portraying how it was adopted by the religious orders in charge of converting the Indigenous people to Catholicism.

While the eagle and cactus were already adopted by Europeans in the mid-16th century, the Jesuits introduced the serpent decades later. “From then on, it would remain a symbol of the city’s identity — one that would also spread throughout the rest of New Spain,” Lozada said.

According to her, plenty of monasteries dating back to the 17th century attest to how friars displayed the eagle and cactus in their sanctuaries. Even today, the emblem can still be seen above the façade of Mexico City’s cathedral and inside one of its chapels.

“Such was the strength of Mexica culture that the evangelizers sought to adopt it rather than exclude it,” she said. “It was like saying, ‘I acknowledge your history.’”

The same logic applied with the European conquerors. Even as they ordered the destruction of the Mexica religious complexes, the representation of the foundational myth was not erased from history.

“For them, conquering a city like Tenochtitlan was a matter of pride and therefore they never intended to deny its existence,” Lozada said. “This meant that the strength of the city buried beneath the new one underlies it and resurfaces — as if it had never disappeared.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

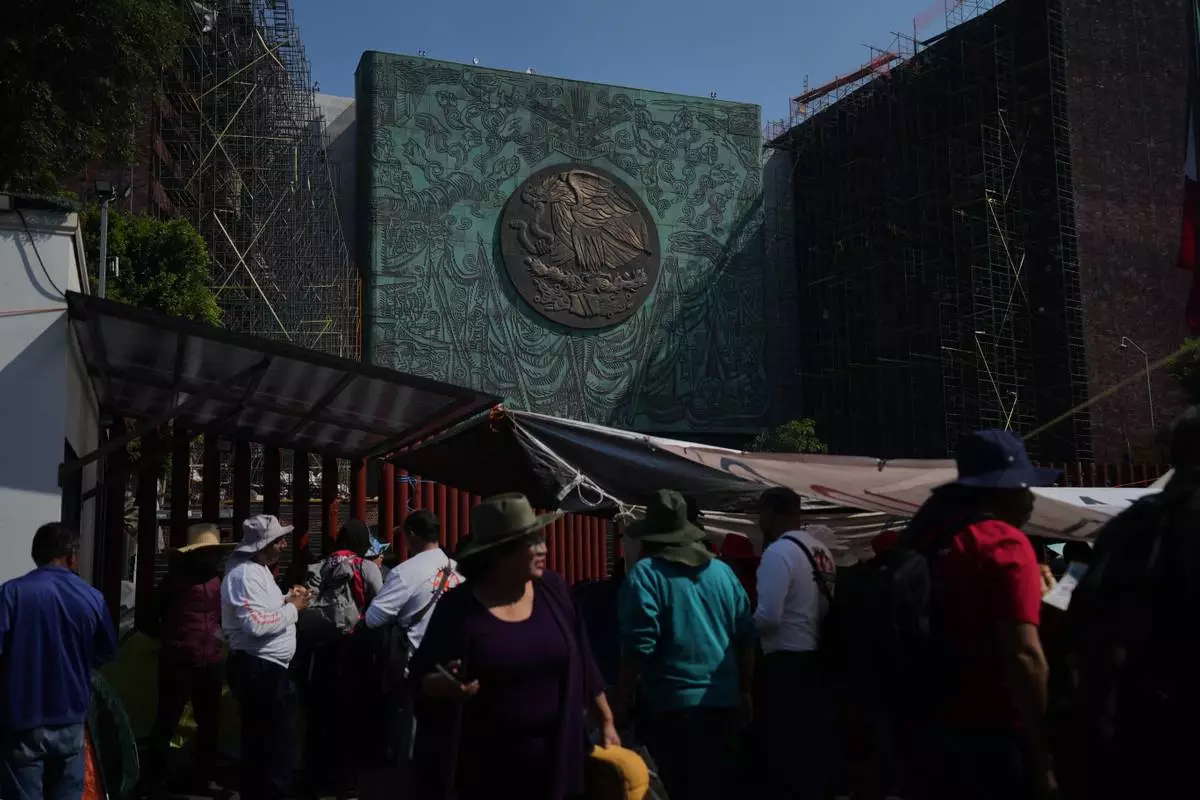

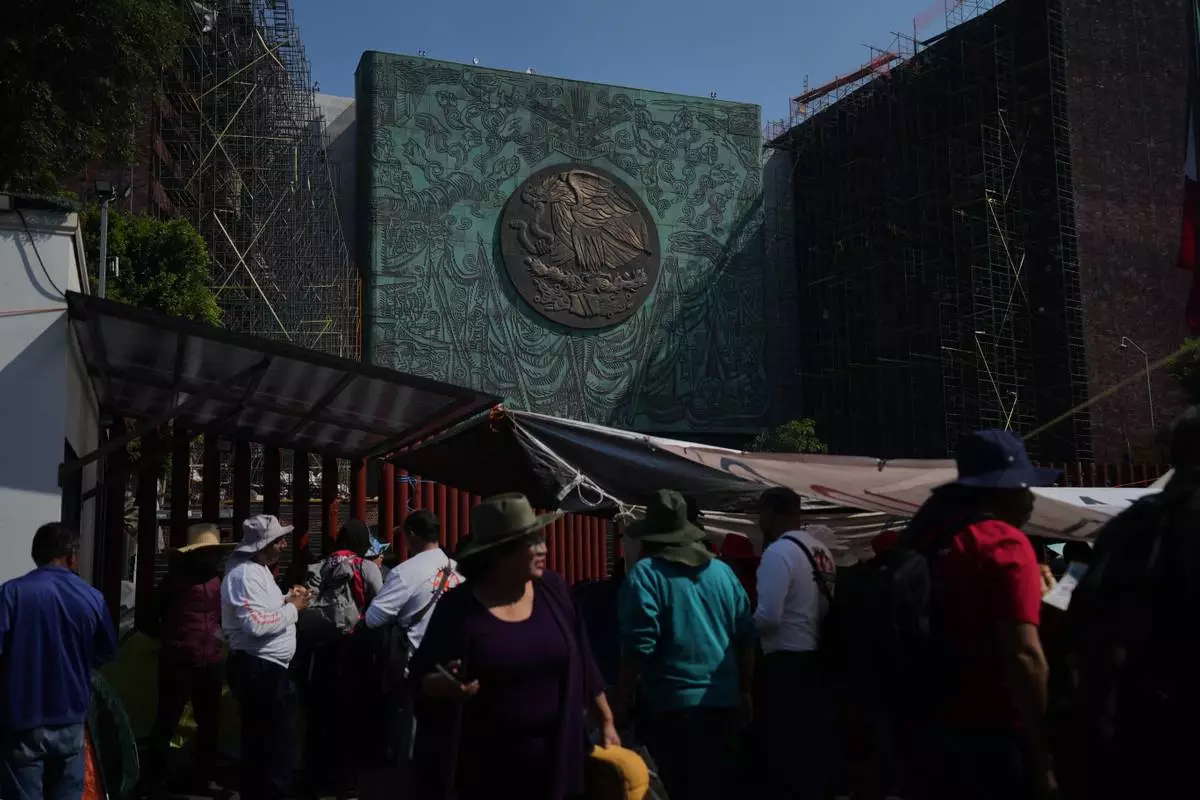

Protesters gather in front of the Legislative Palace of San Lazaro in Mexico City, where the Mexican coat of arms is visible on the building's façade, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

People sit on benches in Plaza del Aguilita, where the evolution of the Mexican coat of arms is showcased, Mexico City, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

The entrance of Mexico City's National Museum of Anthropology features Mexico's national emblem on its façade, Friday, Nov. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

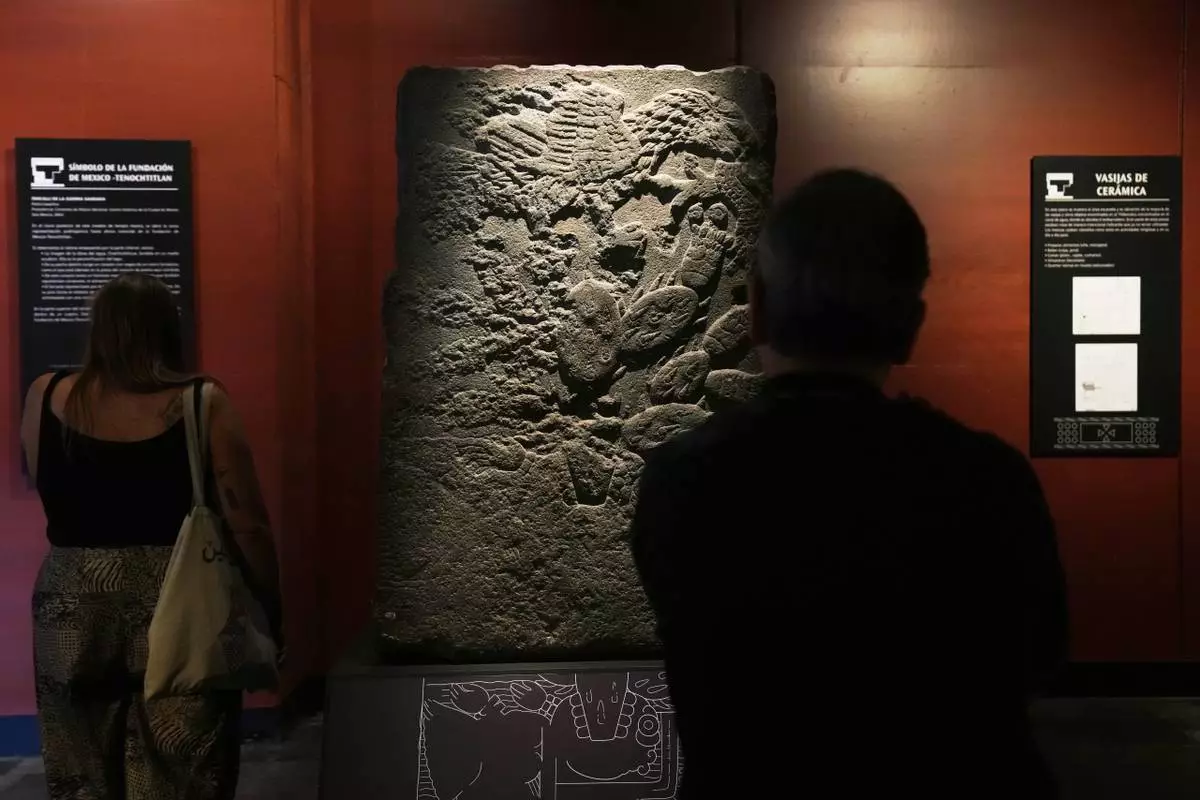

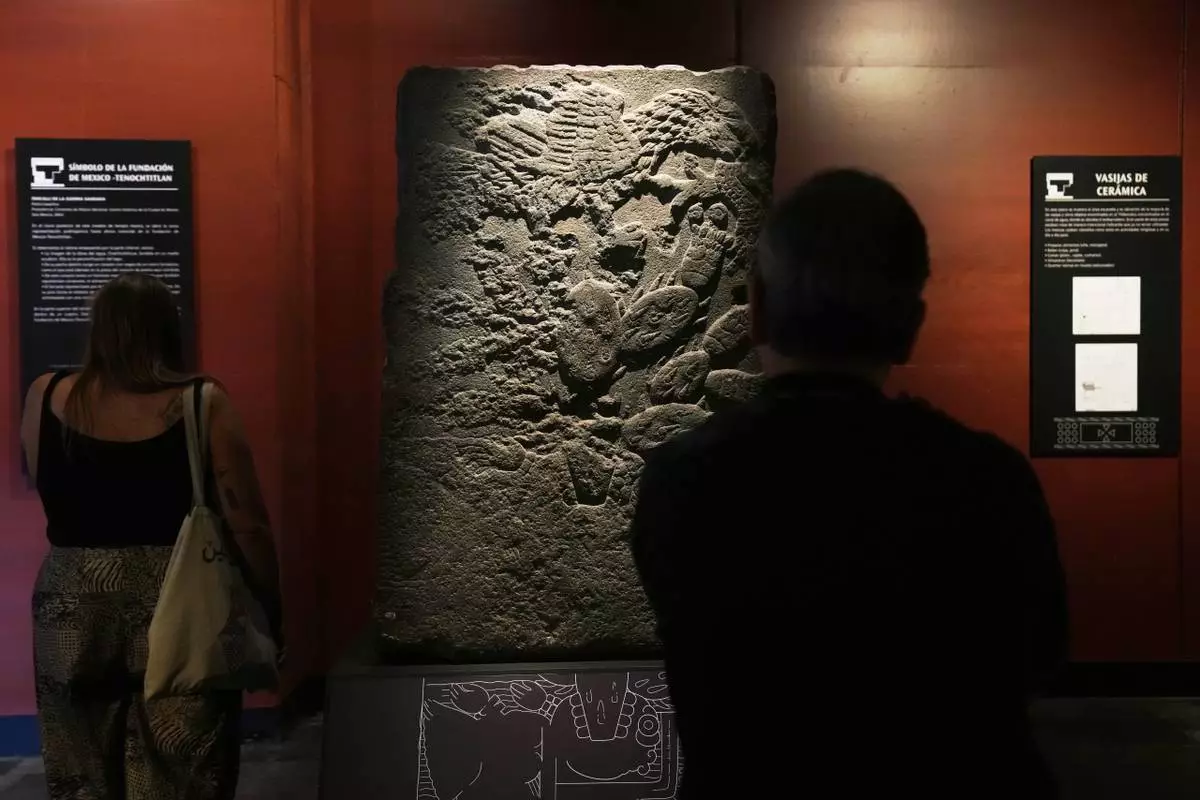

The Teocalli of the Sacred War, the only archaeological piece bearing the carved symbol of Tenochtitlan's founding, an eagle perched on a cactus, is on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, Friday, Nov. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

People at the square of Aguilita in Mexico City walk past a central sculpture depicting Mexico's coat of arms which shows an eagle perched on a cactus devouring a rattlesnake, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

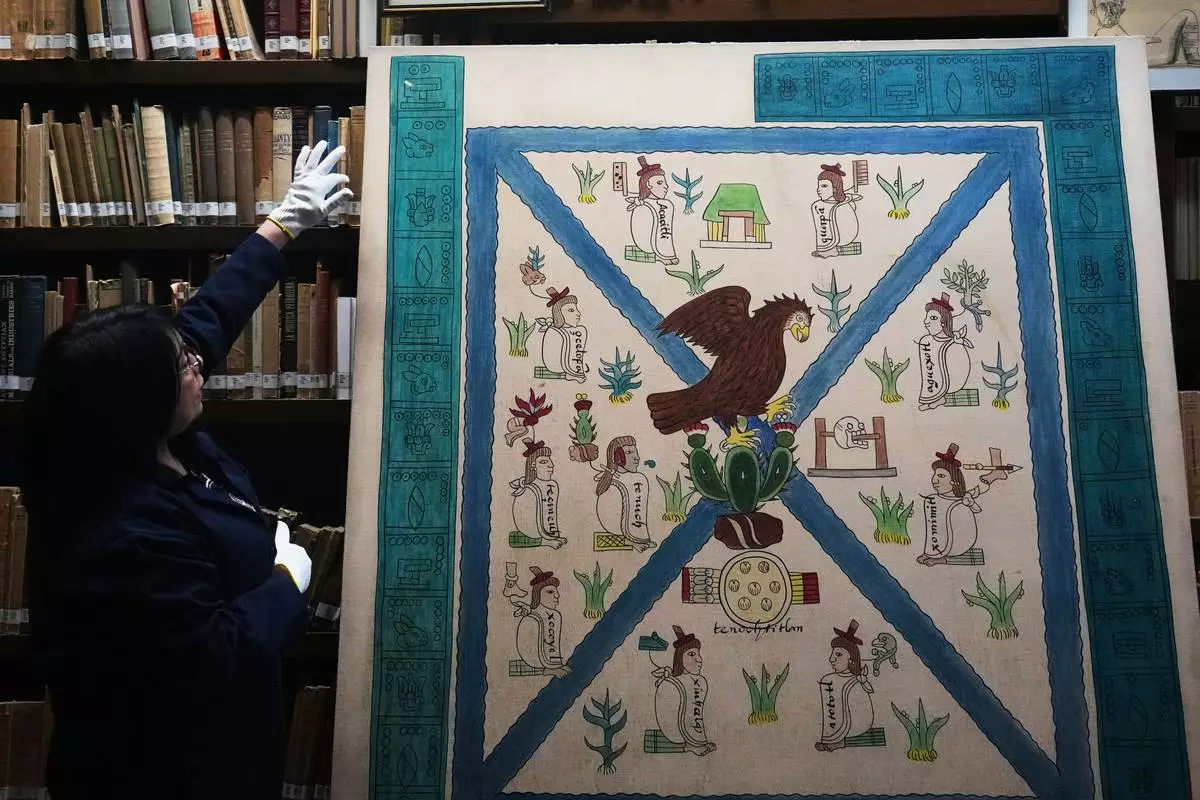

Rosalba Sanchez Flores, a historian at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, points to the details of Mexico's coat of arms as depicted in the Codex Mendoza, Friday, Nov. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

People sit on benches in Plaza del Aguilita, where the evolution of the Mexican coat of arms is showcased, Mexico City, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

People sit at a rooftop bar overlooking Mexico City's Fine Arts Palace, where the Mexican coat of arms is visible atop the building's dome, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)

Mexico's coat of arms decorates a large flag in the city's Zocalo square, Mexico City, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Claudia Rosel)