Adolf Hitler went in wartime for revenge. Angela Merkel plans a pilgrimage in the name of peace. Two German chancellors, with opposite aims and the same destination: a train car in a French forest.

Hitler literally tried to rewrite history in 1940 when the Nazi leader commanded the dining coach to serve France the humiliation Germany suffered in that same spot on the last day of World War I.

This time, Merkel will have the French president by her side as she visits what remains of the Wagon of Compiegne, the carriage-turned-office where the Allies and Germany signed the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918.

FILE - This March 24, 1941 file photo shows the saloon car of Compiegne, in where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

An unusual journey took Wagons-Lits Co. carriage 2419D from serving sauteed veal and boeuf bourguignon to passengers in the seaside town of Deauville to serving as a crucible for world peace while stopped in the middle of a forest in Compiegne.

Puzzled tourists often ask Bernard Letemps, the curator of the Armistice Museum, why the Allies signed the cease-fire agreement that ended the atrocities of the Western Front in that humble setting instead of a grand military building or a glittering palace.

At the time, the official headquarters in Senlis of the Allied commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, would have been the expected place to sign a cease-fire.

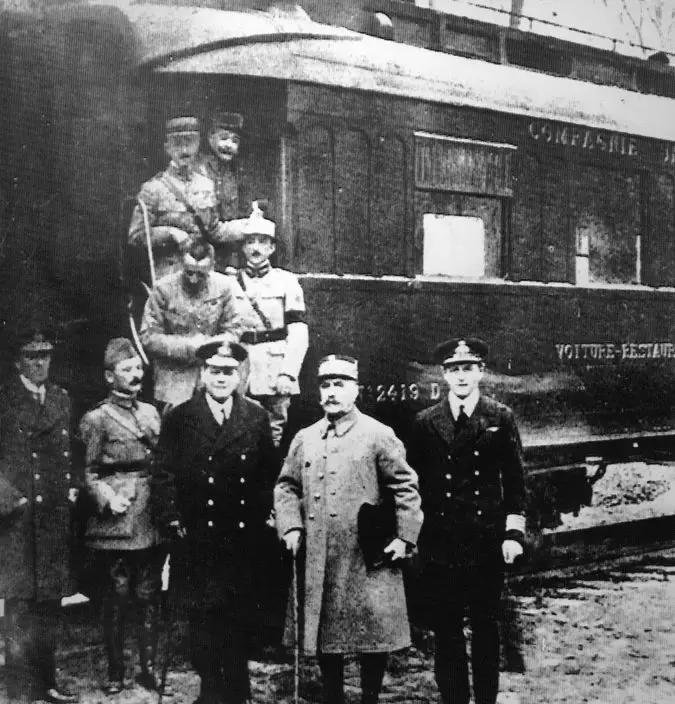

FILE - This undated file photo shows the train wagon in which the armistice of 1918 ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918, in Rethondes, north of Paris. Standing in front of the train are the most important members of the armistice, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, second right, and General Maxime Weygand, second left. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

But the town had endured a brutal German assault. Its inhabitants were taken hostage and its mayor shot in September 1914, before the first Battle of the Marne. How the bruised townspeople would react to the presence of a German delegation, even one coming with the goal of peace, was a serious concern.

"It was out of the question to receive the plenipotentiary Germans in (such a) town," Letemps said.

A moveable train carriage in the nearby Compiegne forest was deemed ideal: The isolated location would deter intruders and the calm and secrecy offered a measure of respect to the defeated Germans.

FILE - In this June, 21 1940 file photo, representatives of Germany with Adolf Hitler, seated second left, and France meet at Compiegne Forest, France, in the railroad dining car to discuss terms during World War II. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

As it happened, Foch had fitted out a mobile office just the month before — a dining car chosen at random from the French passenger train fleet. And so 2419D became known as the "Wagon of Compiegne."

The Armistice was signed just after 5 a.m., but officials held out six hours to put it into effect out of a sense of poetry — the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918. That delay, rather unpoetically, cost lives on both sides at the end of a war that had already left 17 million dead.

"The train car represents the end of fighting. The end, when people found peace," Letemps said.

FILE - Adolf Hitler, right, at Compiegne in 1940 after dictating terms to France for their surrender, in Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP Photo)

He added, smiling: "It fulfilled its role of dining car before becoming famous."

The Armistice Museum lays on the train tracks on the site of the signing in the middle of forest.

Foch was immortalized in statues ubiquitous across France and gave his name to one of the broad, leafy avenues radiating out from the Arc de Triomphe.

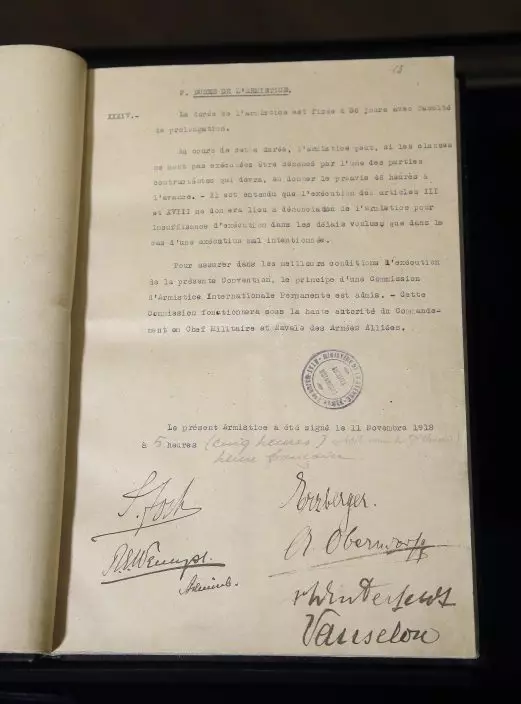

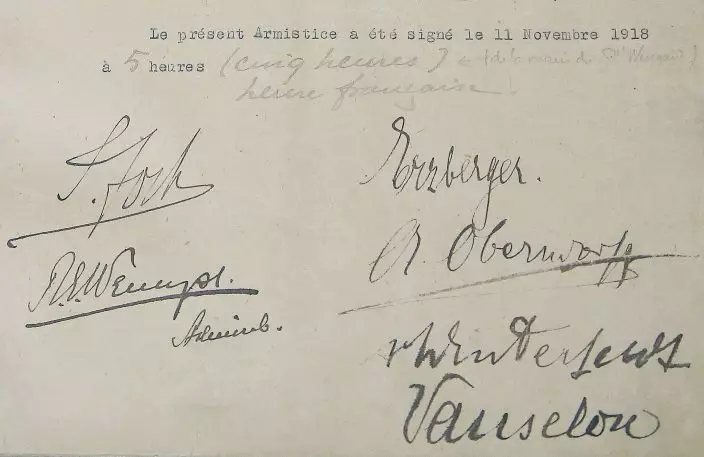

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 photo shows the Armistice document signed by the Allies and the Germans in a carriage in Rethondes, north of Paris, at 05:00 am on Nov. 11, 1918. The document is displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris, France. The Allies signed the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 in a train carriage in Compiegne, north of Paris, that ended hostilities with Germany and put an end to the atrocities of World War I. (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

The same reception was not reserved for the losing side: One of the Germans to sign the document, Matthias Erzberger, was vilified for his role in the surrender. He was assassinated in 1921.

The story of dining car 2419D and Compiegne didn't end with the war.

For throngs of French mourners in the post-war years, the dining car became a shrine to peace and catharsis.

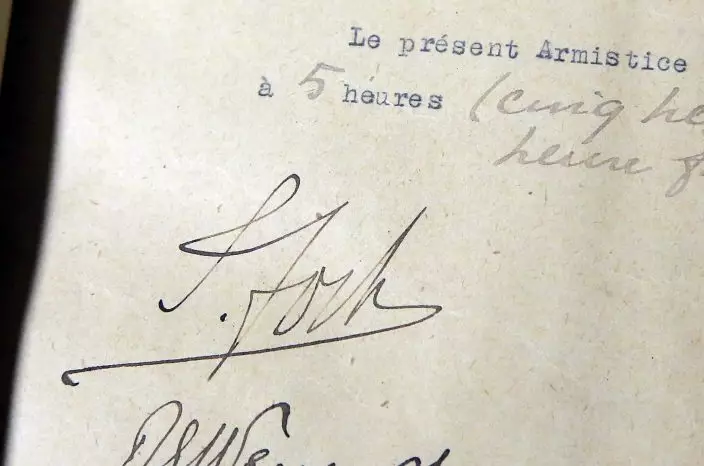

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 picture shows a close view of the signature of French Marshal Ferdinand Foch on the armistice document signed by the Allies and the Germans in a carriage in Rethondes, north of Paris, at 05:00 am on Nov. 11, 1918. The document is displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris, France. The Allies signed the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 in a train carriage in Compiegne, north of Paris, that ended hostilities with Germany and put an end to the atrocities of World War I. (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

The car was taken to Paris for display in the courtyard of the Invalides, the final resting place of Napoleon, before it went back to Compiegne in 1927 to sit in a specially-made memorial constructed on the site of today's museum.

Letemps said the wagon received over 190,000 visitors in one year alone in the 1930s as it became a focus for mourning France's 1.4 million fallen soldiers.

For Hitler in those same years, it became a rallying cry during his ascent to power as he exploited the German public's contempt for the punitive terms of surrender.

This Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 picture shows the signatures of the Allies and Germans on the armistice document dated Nov. 11, 1918 and displayed at the Vincennes castle museum in Vincennes, outside Paris. On left from top : French Marshal Ferdinand Foch and below : British Admiral Lord Wester Wemyss. The German signatures on the right, from the top : Matthias Erzberger head of the German delegation and member of the parliament, Count Alfred von Oberndorff representative of the minister of foreign affair of Germany, General Detlof von Winterfeldt and Captain Ernst Vanselow representing the German Navy. In addition to the signatures the text above reads in French: "The present armistice was signed on Nov. 11, 1918 at 05:00 am French time". (AP PhotoMichel Euler)

The Nazi leader visited the site in 1940 when his armies conquered France.

The Fuhrer ordered the dining car brought out of the memorial and returned to the tracks in the spot in the forest it occupied in 1918.

What ensued was Hitler's surreal theatrical restaging of the 1918 armistice, one of history's most famous events, with literally the tables' turned.

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the interior of the train carriage in which the armistice of the Nov. 11, 1918 was signed, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

The 1940 Armistice was dictated in that train — with Germany the victor and France the loser.

"General (Wilhelm) Keitel read the conditions for the Armistice in the car, with Chancellor Hitler sitting in the place of Marshal Foch," Letemps said.

Hitler then ordered the car to be hauled to Germany and displayed, like a notorious prisoner of war, at the Berlin Cathedral.

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows a model depicting the circumstances of the signing of the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

The dining car was destroyed at the end of World War II, though how that happened has been lost to time. Some accounts blame members of the Nazi SS, others a random airstrike.

In 1950, French manufacturer Wagons-Lits, the company that ran the Orient Express, donated a car from the same series to the museum — 2439D is identical to its ravaged twin from its polished wooden finishes to its studded, leather-bound chairs. It is parked beside the display of the original car remains: a few fragments of bronze decoration and two access ramps.

On Saturday, Merkel becomes the first German chancellor in 78 years to visit the forest clearing where the end of the globe's first conflict was written.

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the museum of the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice in Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

She will be joined by French President Emmanuel Macron in a scene reminiscent of 1984 when Chancellor Helmut Kohl poignantly held President Francois Mitterrand's hand at an ossuary near Verdun.

On the centenary of the conflict's end, this visit will make for soul-searing images of its own.

Thomas Adamson can be followed at Twitter.com/ThomasAdamson_K

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the exact location where the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice was been signed in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)

This Oct. 19, 2018 photo shows the museum of the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice, in the forest of Compiegne, north of Paris. The French and German leaders this weekend will jointly visit the remains of the train carriage where the armistice ending World War I was signed on Nov. 11, 1918. For the French, the dining car became a shrine to peace. For Adolf Hitler, it was a symbol of the humiliation of surrender. The Nazi leader had it dragged to Germany after conquering France in World War II. (AP PhotoThibault Camus)