Step off the dusty cobblestone streets and peek behind nondescript, weather-worn, faded, even grimy brick facades, and encounter the startlingly beautiful courtyard gardens of this central Mexican colonial town.

These oases of beauty and calm claim their roots in the traditional Moorish gardens of ancient Spain. Those, in turn, were inspired by Persian, Roman and Islamic gardens even earlier. The word "paradise" itself means "walled garden."

Alfonso Alarcon, a landscape architect in San Miguel de Allende for nearly 30 years, says monasteries were among the first to design and plant courtyard gardens. Perhaps it was an attempt to replicate paradise.

This Nov. 23, 2018 photo provided by Kim Curtis shows a courtyard garden in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico. Step off the dusty cobblestone streets and peek behind nondescript, weather-worn brick facades and encounter the startlingly beautiful courtyard gardens of the central Mexican town of San Miguel de Allende. These oases of beauty and calm claim their roots in the traditional Moorish gardens of ancient Spain. (Kim Curtis via AP)

"Life was directed inside" initially for safety reasons, he explained. "No one saw you. It looks like nothing from the outside, and then you get into this beautiful patio."

Traditionally, such gardens are built in a cross-shape with the corners, usually anchored by large trees, pointing north, south, east and west. A pond or fountain often serves as a central focal point. Fruit trees and fragrant plants provide further respite from the sun, humidity, even the noise and dirt from outside the walls.

In the 16th century, the conquering Spaniards left behind their outdoor sanctuaries, and they continue to be embraced in Mexico today.

This Nov. 23, 2018 photo provided by Kim Curtis shows a courtyard garden in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico. Step off the dusty cobblestone streets and peek behind nondescript, weather-worn brick facades and encounter the startlingly beautiful courtyard gardens of the central Mexican town of San Miguel de Allende. These oases of beauty and calm claim their roots in the traditional Moorish gardens of ancient Spain. (Kim Curtis via AP)

Markus Luck has been designing gardens in San Miguel since 2006. "You want something that looks good year-round," he explains. "Put in things that aren't too big, don't block too much light, aren't too cluttered."

In smaller spaces, the entire courtyard can even be filled with plants in pots.

Mexican walls are often painted bold reds and yellows and oranges, so trees and plants tend toward simple, wide, leafy greens, or crawling ivy and simple white blooms.

Because of its mild, Mediterranean climate, just about anything can grow — and quickly — in San Miguel. Popular choices for courtyard gardens include citrus trees, including oranges, limes and kumquats, olive trees, bougainvillea, ferns and lavender.

"I would see something in front of someone's house and I'd knock on the door and ask for a cutting," Luck said. "You'd see the ones over time that do well."

Modern designers and property owners also are paying more attention to how much water their gardens will use and how much work will be required to maintain them.

San Miguel uses well water stored in ancient aquifers, so it's chock full of salt and other minerals, Luck said.

Jeffry Weisman and Andrew Fisher first fell in love with the three jacaranda trees on the property they bought here in 2011.

"I grew up in L.A. with a jacaranda outside my window. It was minuscule compared to these that are 110 years old," Weisman said. "Nothing like an ancient tree to give scale and sculptural quality to a garden."

The main building on the couple's property was originally built in the 18th century as a tannery, so it's more open and less claustrophobic than most, Weisman explained. He said they designed the courtyard as a series of rooms, each with a theme and purpose, from the pool area to the dining terrace to the outdoor living room with fireplace.

"For the planting, it was critical that everything be easy to grow and native," he said.

"In our youth, we spent a lot of time trying to grow things that didn't want to grow, and we've learned better."

Alarcon said he still meets clients who want what they can't — or shouldn't — have.

"Gardens work as a dynamic unit. Everything should work with everything else," he said, adding that he encourages property owners to think past their immediate enjoyment to the mid- or long-term.

"Gardens don't remain the same. Even if you try to control it. Plants grow old, they die, they change."

Alfonso Alarcon: www.terralandscapedesign.com

Markus Luck: www.sozolandscape.com

Jeffry Weisman: www.fisherweisman.com

Andrew Fisher: www.andrewfisherart.com

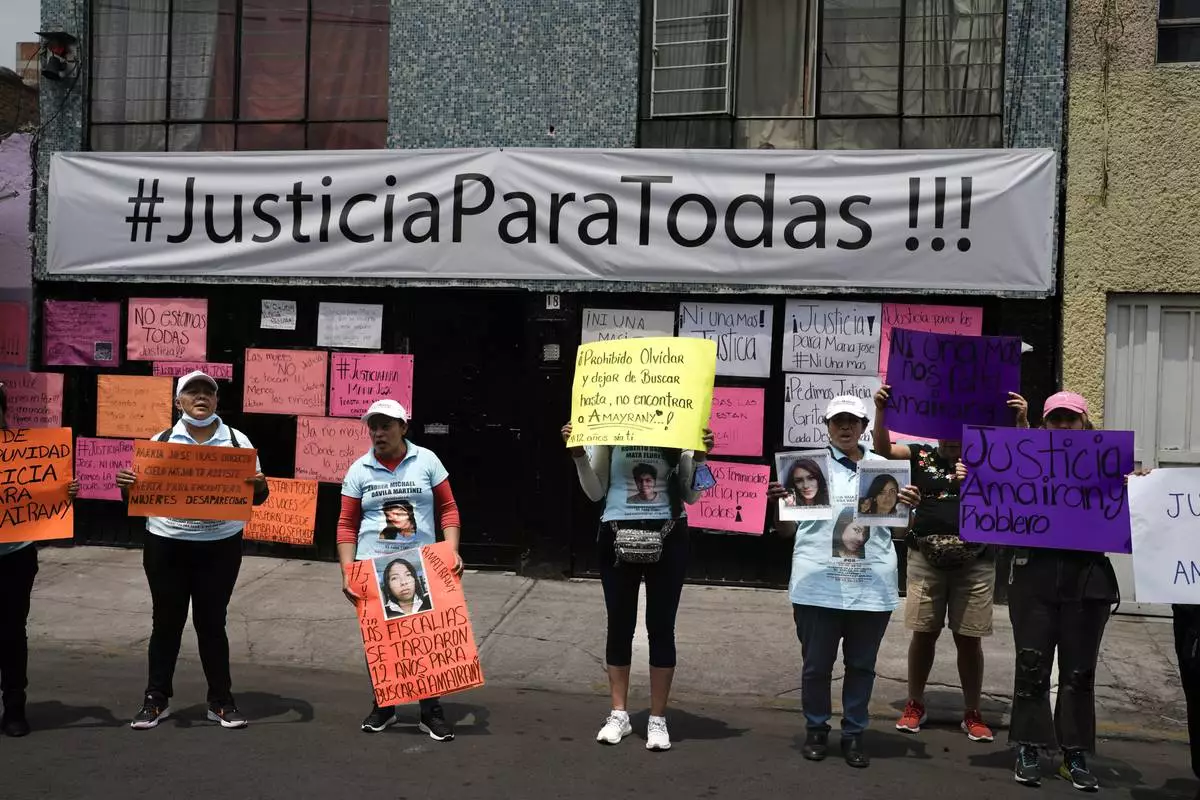

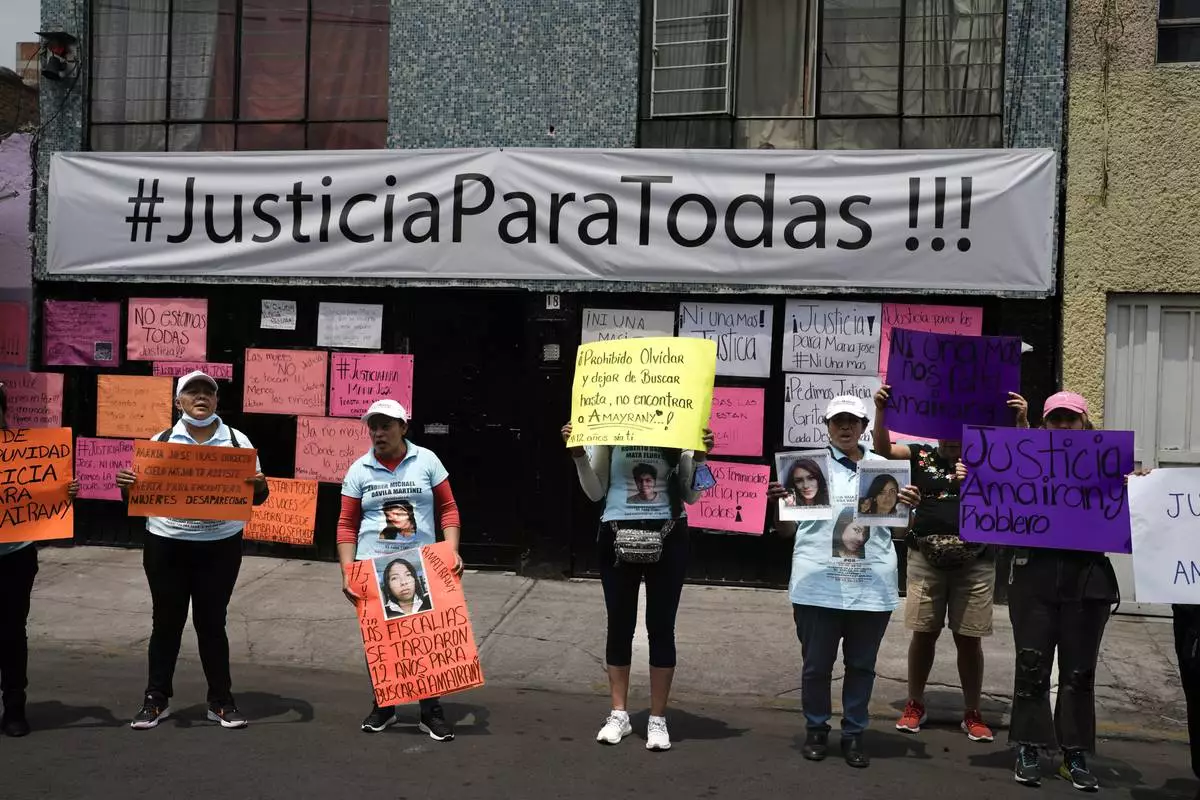

MEXICO CITY (AP) — The family and supporters of a missing woman who may have been the first victim of a Mexico City serial killer protested Friday at the site where the bones and possessions of a half-dozen women were found last week.

Protesters covered the facade of the apartment building with placards after investigators found the bones, cell phones and ID cards of several women at rented rooms there, apparent mementos of the killer's 12-year trail of victims.

Most of the placards taped to the non-descript apartment building on the city's east side Friday asked variants of a single question: Why did it take prosecutors 12 years to investigate the disappearance of Amairany Roblero, then 18.

The high school student vanished in 2012 and her parents never heard from her — or investigators — until last week, a pattern all too familiar in missing persons cases in Mexico, where prosecutors often leave it up to relatives to investigate.

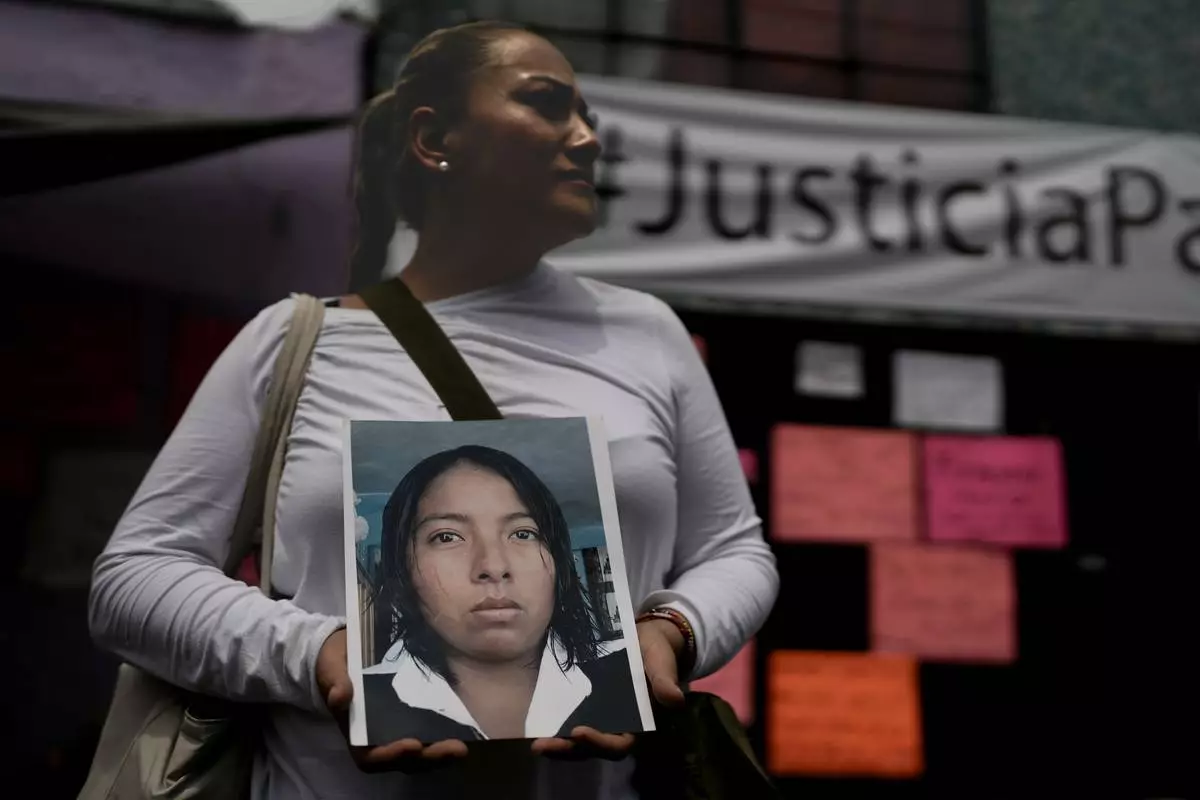

“The prosecutors had the case file, but they didn't ever give any results to her parents,” said Alejandra Jiménez, a family friend who accompanied Amairany's parents in their search and at Friday's protest.

Her parents “printed up flyers, and they distributed them outside of her school” — the last place she was seen — “but her parents had nothing, nowhere to start, nor any directions to the end.”

In fact, prosecutors never caught the killer. It was neighbors and police who detained him last week after he allegedly broke into a neighbor’s apartment to kill his seventh victim, was interrupted and left a surviving witness.

The suspect — who was only identified by his first name, Miguel, according to Mexican law — apparently waited for a woman to leave her apartment last week and then rushed in and sexually abused and strangled her 17-year-old daughter.

The mother returned and saw the man leaving, but he slashed her in the neck and fled, authorities said. The mother survived but her daughter did not.

The suspect lived near the scene of the crime, and he was quickly identified and arrested. He has been ordered held over for trial on charges of murder and attempted murder, both related to the most recent victims.

While Mexico City authorities sought Thursday to downplay the case — city prosecutor Ulises Lara contended the killer was essentially unstoppable because “he showed no signs of violent or aggressive behavior in his daily life" — protesters weren't buying those excuses.

“They (authorities) have all the means to look for missing people,” Jiménez said. “Instead of focusing on their political campaigns, they should help all the women who are looking for their children.”

This week, prosecutors finally called Amairany's parents to tell them they had found unspecified “evidence” related to their daughter in a room the suspect rented.

Previously, investigators said they found blood stains, bones, a saw, cellphones and missing women’s ID cards, as well as other “biological material” in the rooms. They also found “a series of notebooks that may well be narrations of the acts that Miguel carried out against his victims.”

“But they haven't shown her parents any belongings, no clothing, no photo, nothing,” said Jiménez. “This is wearing down her parents physically, mentally.”

Juan Carlos Gutiérrez, a lawyer who represents the family of another suspected victim, questioned why authorities didn’t investigate her disappearance earlier — acting only when evidence linked to her case showed up at the suspect’s apartment.

“Why was there never an investigation, why were people never interviewed, despite missing person reports being filed starting in 2015?” Gutiérrez said.

Without proper funding, training or professionalism, prosecutors in Mexico’s capital have routinely failed to stop serial killers until the number of victims reaches a point that can’t be ignored.

In 2021, a serial killer in a Mexico City suburb was only caught after years of alleged crimes — 19 bodies were found hacked up and buried at his house — because his final victim was the wife of a police commander. The commander burst into the suspect's house with a bunch of other cops, only to find a scene of horror.

In 2018, a serial killer in Mexico City responsible for the deaths of at least 10 women was caught only when he was found pushing a dismembered body down the street in a baby carriage. He had dumped most of the bodies of his victims in vacant lots.

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

A basket of flowers sits next to a poster of Amarirany Roblero who went missing 12 years ago, during a protest outside an apartment rented by a suspected serial killer where evidence related to Roblero was found, in the Iztacalco neighborhood of Mexico City, Friday, April 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

Friends and family holds images of women who have gone missing, during a protest outside an apartment rented by a suspected serial killer, in the Iztacalco neighborhood of Mexico City, Friday, April 26, 2024. Protesters covered the facade of the building with placards after investigators found the bones, cell phones and ID cards of several women at rented rooms there. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

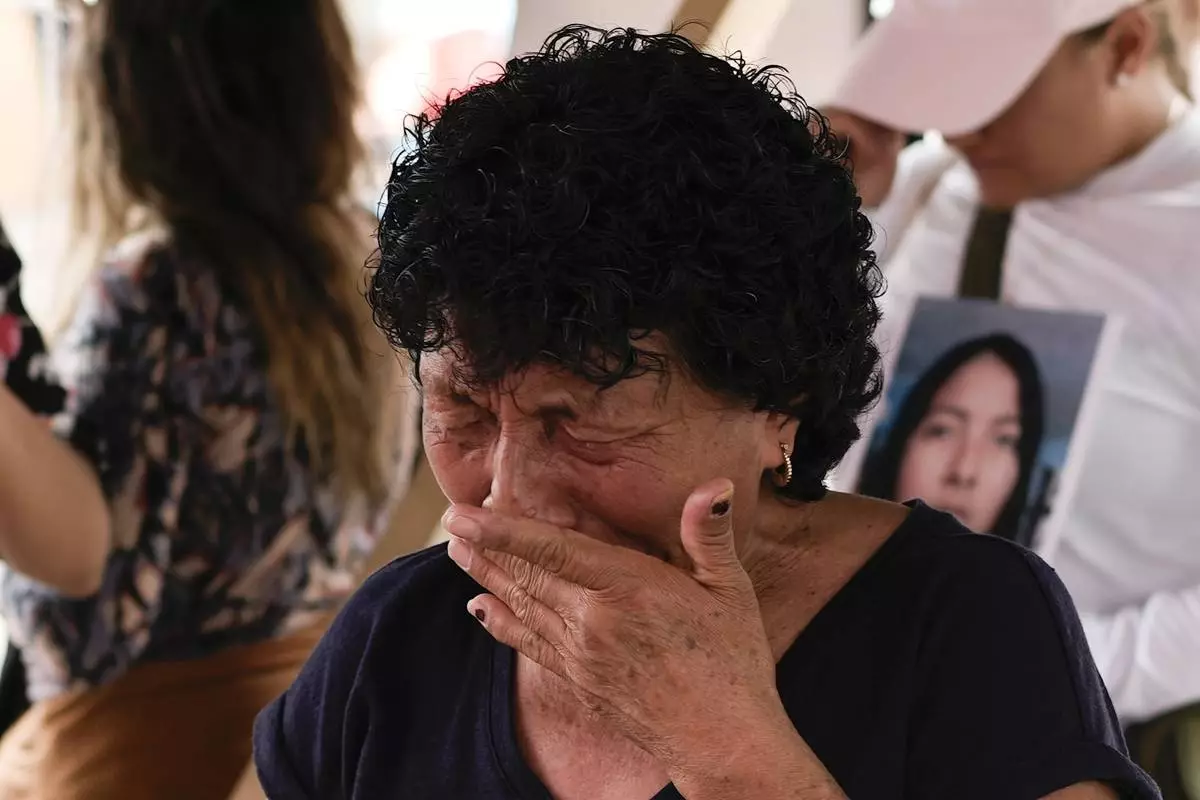

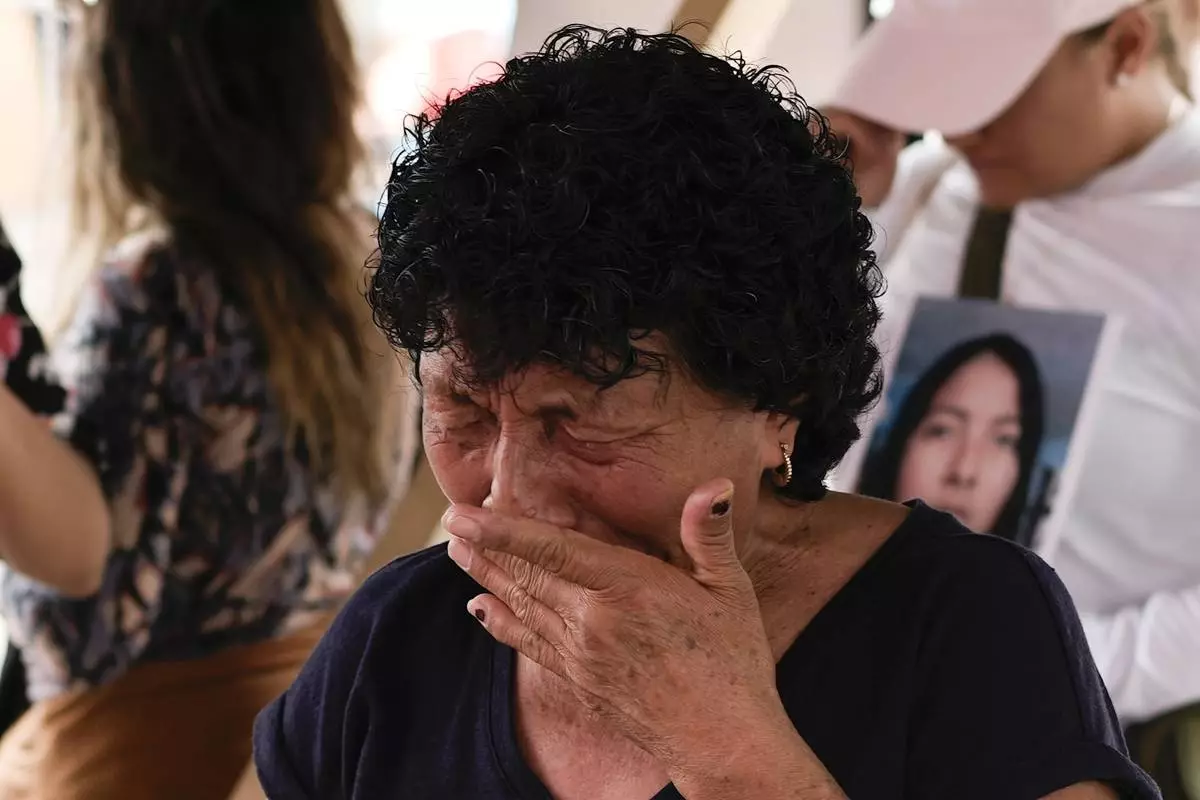

Cecilia Gonzalez, the mother of Amarirany Roblero, who went missing 12 years ago, cries during a protest outside an apartment rented by a suspected serial killer where evidence related to her daughter was found, in the Iztacalco neighborhood of Mexico City, Friday, April 26, 2024. Protesters covered the facade of the building with placards after investigators found the bones, cell phones and ID cards of several women at rented rooms there, asking variants of a single question: Why did it take prosecutors 12 years to investigate the disappearance of Amairany Roblero, then 18. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

Mario Roblero and Cecilia Gonzalez hold images of their missing daughter Amarirany Roblero, during a protest outside an apartment rented by a suspected serial killer, in the Iztacalco neighborhood of Mexico City, Friday, April 26, 2024. Protesters covered the facade of the building with placards after investigators found the bones, cell phones and ID cards of several women at rented rooms there, asking variants of a single question: Why did it take prosecutors 12 years to investigate the disappearance of Amairany Roblero, then 18. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

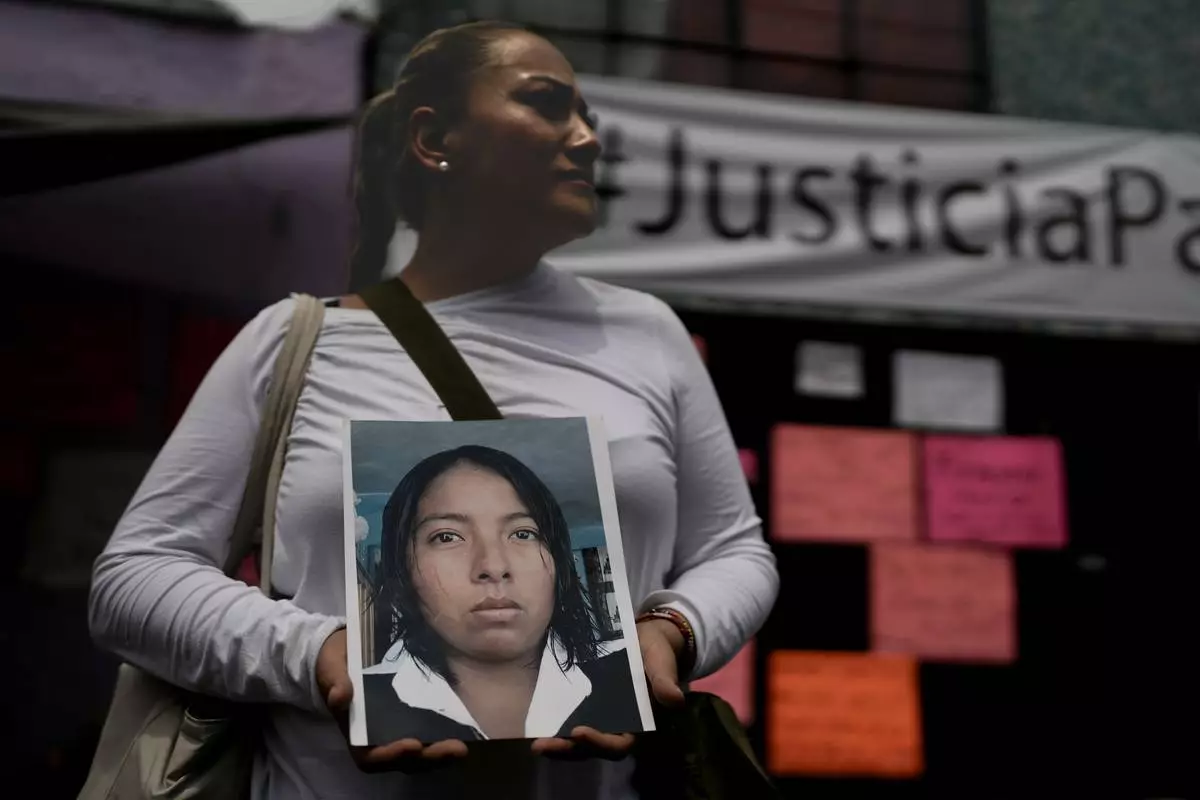

Alejandra Jiménez holds an image of Amarirany Roblero who went missing 12 years ago, during a protest outside an apartment rented by a suspected serial killer, in the Iztacalco neighborhood of Mexico City, Friday, April 26, 2024. Protesters covered the facade of the building with placards after investigators found the bones, cell phones and ID cards of several women at rented rooms there, asking variants of a single question: Why did it take prosecutors 12 years to investigate the disappearance of Amairany Roblero, then 18. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)