Jennie Lyon Marrian believes the monitors provide “false reassurance” to expectant mothers.

A grieving mum who lost her baby at 34 weeks – just days before Christmas – has issued a heart-wrenching plea for home doppler kits to be ditched, believing they provide false reassurance.

Click to Gallery

Jennie has since had a daughter Zoë, now nine months, with her IT consultant husband, Pete, 36, but thinks about Sophie every day and backs the charity Kicks Count’s warnings not to give pregnant loved ones home doppler kits for Christmas, saying: “Unless you’re a qualified medical professional, there’s the risk that, when using a doppler, you’ll either confuse the mum’s heartbeat, or the umbilical flow for the baby’s.

Jennie Lyon Marrian believes the monitors provide “false reassurance” to expectant mothers.

Jennie has since had a daughter Zoë, now nine months, with her IT consultant husband, Pete, 36, but thinks about Sophie every day and backs the charity Kicks Count’s warnings not to give pregnant loved ones home doppler kits for Christmas, saying: “Unless you’re a qualified medical professional, there’s the risk that, when using a doppler, you’ll either confuse the mum’s heartbeat, or the umbilical flow for the baby’s.

Fairly early in her pregnancy with Sophie, Jennie was told she had an anterior placenta, meaning it had attached to the front wall of the uterus.

“It was never meant to be for reassurance – we simply wanted it for the thrill of being able to hear her heartbeat in between appointments,” Jennie explained.

“Pete and I got the doppler out to check, and I am still convinced to this day I could hear Sophie’s heartbeat,” she said. “We are sensible, logical people and would never take risks, but it was the weekend before Christmas and we were rushing around to get things ready.

“It’d happened some time in the previous 48 hours,” said Jennie. “It was such a horrible shock, like a nightmare I couldn’t wake up from.

After being sent home to process the news, Jennie returned to hospital two days later, when she faced the harrowing task of delivering her stillborn daughter.

In the wake of her loss, Jennie made a vow to spare other parents her pain.

Also, earlier this year, the Department of Health announced a Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA) review of fetal dopplers, and a bill to regulate sales of them is due for a second reading in Parliament in January 2019.

She continued: “It was hard going in to give birth again, as it was at the same hospital where I’d lost Sophie. But Zoë is a rainbow baby in every sense of the word.

When stay-at-home mum Jennie Lyon Marrian, 41, of Southampton, Hampshire, realised her unborn daughter, Sophie, had not moved in the womb overnight, she used her doppler – a type of hand-held monitor – and is “certain” she could hear a heartbeat.

But, unable to shake the nagging feeling something was wrong, she went to hospital for a scan and was devastated to be told that her baby had died in the womb, following a fatal haemorrhage.

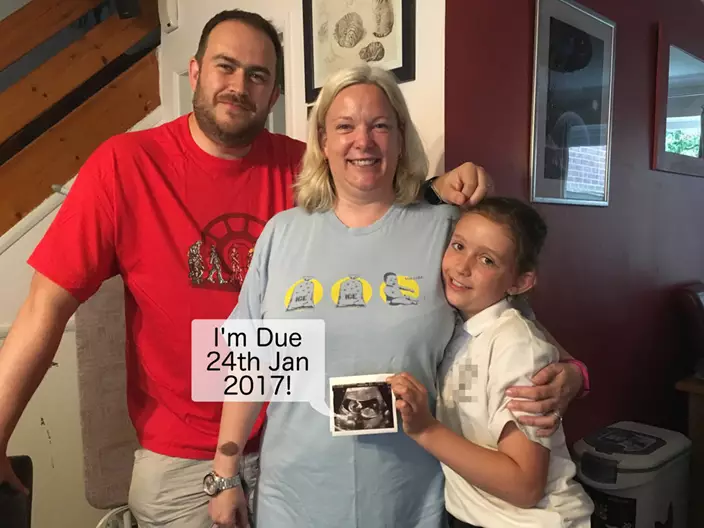

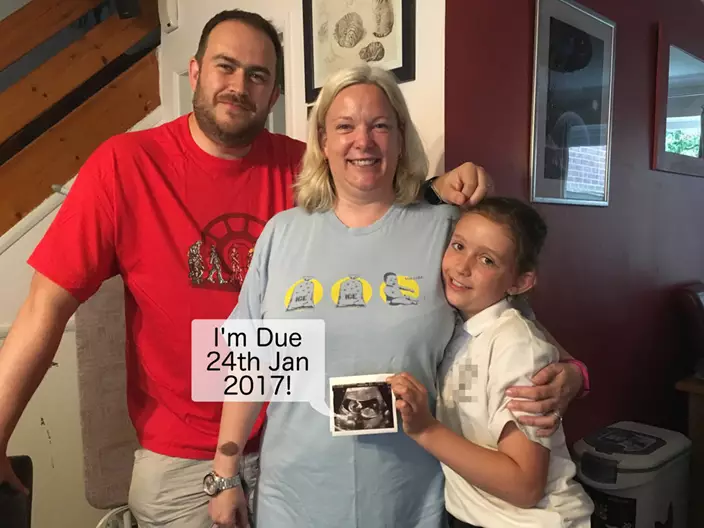

Jennie, Madison, Pete and Zoë (PA Real Life/Collect)

Jennie has since had a daughter Zoë, now nine months, with her IT consultant husband, Pete, 36, but thinks about Sophie every day and backs the charity Kicks Count’s warnings not to give pregnant loved ones home doppler kits for Christmas, saying: “Unless you’re a qualified medical professional, there’s the risk that, when using a doppler, you’ll either confuse the mum’s heartbeat, or the umbilical flow for the baby’s.

“I wish every day that I hadn’t trusted the doppler I used. I’ll never know if things would’ve been different, if they could have saved her, had I gone straight to a hospital. The ‘what ifs’ I relive every single day are the reason I am fully backing the Ditch the Doppler campaign.

“Get to know your baby’s routine and, if anything changes at all, don’t hesitate to go straight to hospital. Midwives would far prefer to scan you 20 times and tell you everything is okay, than sit across from you once and break the awful news I had to hear.”

Sophie's 12 week scan (PA Real Life/Collect)

Fairly early in her pregnancy with Sophie, Jennie was told she had an anterior placenta, meaning it had attached to the front wall of the uterus.

Although this is completely normal, it can cushion the baby’s movements, making them harder to feel.

Having already used a doppler, when they were having their eldest daughter, Madison, now 11, Jennie and Pete decided to get one for her pregnancy with Sophie, too.

Sophie's memory corner (PA Real Life/Collect)

“It was never meant to be for reassurance – we simply wanted it for the thrill of being able to hear her heartbeat in between appointments,” Jennie explained.

As the position of her placenta meant she was not always able to feel Sophie moving much, Jennie went back and forth to hospital for scans to put her mind at ease – and every time, things were perfectly fine.

Then, on 17 December, 2016, when she was 34 weeks pregnant, she woke up realising she had not really felt her baby move overnight.

Madison with Zoë and a bear containing Sophie's ashes (PA Real Life/Collect)

“Pete and I got the doppler out to check, and I am still convinced to this day I could hear Sophie’s heartbeat,” she said. “We are sensible, logical people and would never take risks, but it was the weekend before Christmas and we were rushing around to get things ready.

“Having the anterior placenta, I’d become used to not being able to feel much movement, so in that moment, the doppler helped calm my anxieties. I know now, though, that just because you can hear a heartbeat, it doesn’t mean the baby isn’t in distress.

“All a doppler does is provide a quick snapshot – it’s not like having a full trace scan done, where someone with medical training can work out a pattern and pick up on things like the heart rate decelerating.”

Despite using the doppler, for the rest of the day, Jennie felt something was wrong and, when she used it again in the evening and could not detect any sound, she headed straight to Southampton’s Princess Anne Hospital.

There, an urgent scan tragically determined that Sophie had died in the womb.

A post-mortem later revealed she had suffered a fetomaternal haemorrhage, meaning her blood was lost in her mother’s circulation.

Jennie holding Sophie's hand (PA Real Life/Collect)

“It’d happened some time in the previous 48 hours,” said Jennie. “It was such a horrible shock, like a nightmare I couldn’t wake up from.

“Pete had to phone round the family and break the news and, because Madison was with us as there’d been nobody to leave her with, we had to tell her, too, that the sister she so desperately wanted had gone.

“She has an old head on young shoulders, but she was only nine then, and couldn’t understand why Sophie wasn’t coming home.”

Pete, Zoë and Sophie's bear (PA Real Life/Collect)

After being sent home to process the news, Jennie returned to hospital two days later, when she faced the harrowing task of delivering her stillborn daughter.

She continued: “When it first happened, I’d wanted a c section. But then Madison said to me, ‘Every time you look at the scar though, Mummy, you’ll be sad.’

“I realised she was right. So, I had to deliver Sophie naturally, knowing I would never get to take her home. At 9:06pm on 19 December, my angel was born and went straight to heaven.”

Zoë and Madison (PA Real Life/Collect)

In the wake of her loss, Jennie made a vow to spare other parents her pain.

And, after reading about Kicks Count, a leading pregnancy and stillbirth charity, online, she put her full support behind their Ditch the Doppler campaign.

Launching in 2017, the movement aims to regulate or ban the sale of home dopplers to expectant parents in the UK.

So far, retail giant Mothercare has agreed to discontinue sales once existing stocks have run out and price comparison company Idealo has pledged its support – removing all dopplers from its site.

Some roses planted in Sophie's memory (PA Real Life/Collect)

Also, earlier this year, the Department of Health announced a Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA) review of fetal dopplers, and a bill to regulate sales of them is due for a second reading in Parliament in January 2019.

Meanwhile, as she threw her weight behind the Kicks Count campaign, Jennie discovered she was expecting again.

Calling her daughter, born in March 2018, Zoë, after a midwife who showed her exceptional care and another mother she had bonded with, she is her ‘rainbow baby ‘ – the name given to a baby born after a loss, like a stillbirth.

Zoë, Jennie and Pete's 'rainbow baby' (PA Real Life/Collect)

She continued: “It was hard going in to give birth again, as it was at the same hospital where I’d lost Sophie. But Zoë is a rainbow baby in every sense of the word.

“I still think of Sophie every single day, and there are times when it all feels very surreal, but I am determined to live well to honour her memory.”

Jennie's Facebook announcement photo from when she was pregnant with Sophie (PA Real Life/Collect)

For information, visit www.kickscount.org.uk

KIGALI, Rwanda (AP) — Rwanda says it's ready to receive migrants from the United Kingdom after British Parliament this week approved a long-stalled and controversial bill seeking to stem the tide of people crossing the English Channel in small boats by deporting some of them to the East African country.

There is even a place ready and waiting for the migrants — a refurbished Hope Hostel in the vibrant upscale neighborhood of Kagugu, an area of the Rwandan capital of Kigali that is home to many expats and several international schools.

The hostel once housed college students whose parents died in the 1994 genocide, this African nation’s most horrific period in history when an estimated 800,000 Tutsi were killed by extremist Hutu in massacres that lasted over 100 days.

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has pledged the deportation flights would begin in July but has refused to provide details or say about how many people would be deported.

Rwanda government's deputy spokesperson Alain Mukuralinda told The Associated Press on Tuesday that authorities here have been planning for the migrants' arrival for two years.

“Even if they arrive now or tomorrow, all arrangements are in place,” he said.

The plan was long held up in British courts and by opposition from human rights activists who say it is illegal and inhumane. It envisages deporting to Rwanda some of those who enter the U.K. illegally and migrant advocates have vowed to continue to fight against the plan.

The measure is also meant to be a deterrent to migrants who risk their lives in leaky, inflatable boats in hopes that they will be able to claim asylum once they reach Britain. The U.K. also signed a new treaty with Rwanda to beef up protections for migrants, and adopted new legislation declaring Rwanda to be a safe country.

“The Rwanda critics and the U.K. judges who earlier said Rwanda is not a safe country have been proven wrong,” Mukuralinda said. “Rwanda is safe.”

The management at the four-story Hope Hostel says the facility is ready and can accommodate 100 people at full capacity. The government says it will serve as a transit center and that more accommodations would be made available as needed.

Thousands of migrants arrive in Britain every year.

After they arrive from Britain, the migrants will be shown to their rooms to rest, after which they will be offered food and given some orientation points about Kigali and Rwanda, said hostel manager Ismael Bakina.

Tents will be set up within the hostel's compound for processing their documentation and for various briefings. The site is equipped with security cameras, visible across the compound.

Within the compound are also entertainment places, a mini-soccer field, a basketball and a volleyball court as well as a red-carpeted prayer room. For those who want to light up, "there is even a smoking room," Bakina explained.

Meals will be prepared in the hostel's main kitchen but provisions are also being made for those who want to prepare their own meals, he said. The migrants will be free to walk outside the hostel and even visit the nearby Kigali city center.

“We will have different translators, according to (their) languages," Bakina added, saying they include English and Arabic.

The government has said the migrants will have their papers processed within the first three months. Those who want to remain in Rwanda will be allowed to do so while authorities will also assist those who wish to return to their home countries.

While in Rwanda, migrants who obtain legal status — presumably for Britain — will also be processed, authorities have said, though it's unclear what that means exactly.

For those who choose to stay, Mukurilinda said Rwanda's government will bear full financial and other responsibilities for five years, after which they will be considered integrated into the society.

At that point, they can start managing on their own.

Follow AP’s global migration coverage at: https://apnews.com/hub/migration

A view of Hope Hostel one of the locations where the asylum seekers from the U.K. are expected to arrive in the next 10-12 weeks in Kigali, Rwanda, Wednesday, April 24, 2024. The management of the hostel where the migrants are to stay in, Hope Hostel, says the facility is ready to accommodate 100 migrants. (AP Photo/Atulinda Allan)

A view of Hope Hostel one of the locations where the asylum seekers from the U.K. are expected to arrive in the next 10-12 weeks in Kigali, Rwanda, Wednesday, April 24, 2024. The management of the hostel where the migrants are to stay in, Hope Hostel, says the facility is ready to accommodate 100 migrants. (AP Photo/Atulinda Allan)

A basketball court with a volleyball play ground at Hope Hostel, where U.K. asylum seekers from the U.K. are expected to arrive in the next 10-12 weeks in Kigali, Rwanda, Wednesday, April 24, 2024. The management of the hostel where the migrants are to stay in, Hope Hostel, says the facility is ready to accommodate 100 migrants. (AP Photo/Atulinda Allan)

FILE - A security guard stands in the reception area of the Hope Hostel, which is one of the locations expected to house some of the asylum-seekers due to be sent from Britain to Rwanda, in the capital Kigali, Rwanda on June 10, 2022. Rwanda government's deputy spokesperson Alain Mukuralinda said Tuesday, April 23, 2024, it's ready to receive migrants from the United Kingdom after British Parliament this week approved a long-stalled bill seeking to stem the tide of people crossing the English Channel in small boats by deporting some to the East African country. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A bedroom is seen inside the Hope Hostel, which is one of the locations expected to house some of the asylum-seekers due to be sent from Britain to Rwanda, in the capital Kigali, Rwanda on June 10, 2022. Rwanda government's deputy spokesperson Alain Mukuralinda said Tuesday, April 23, 2024, it's ready to receive migrants from the United Kingdom after British Parliament this week approved a long-stalled bill seeking to stem the tide of people crossing the English Channel in small boats by deporting some to the East African country. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - The interior of the Hope Hostel, which is one of the locations expected to house some of the asylum-seekers due to be sent from Britain to Rwanda, is seen in the capital Kigali, Rwanda on June 10, 2022. Rwanda government's deputy spokesperson Alain Mukuralinda said Tuesday, April 23, 2024, it's ready to receive migrants from the United Kingdom after British Parliament this week approved a long-stalled bill seeking to stem the tide of people crossing the English Channel in small boats by deporting some to the East African country. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - The exterior of the Hope Hostel, which is one of the locations expected to house some of the asylum-seekers due to be sent from Britain to Rwanda, is seen in the capital Kigali, Rwanda on June 10, 2022. Rwanda government's deputy spokesperson Alain Mukuralinda said Tuesday, April 23, 2024, it's ready to receive migrants from the United Kingdom after British Parliament this week approved a long-stalled bill seeking to stem the tide of people crossing the English Channel in small boats by deporting some to the East African country. (AP Photo, File)