NASA's New Horizons spacecraft has survived the most distant exploration of another world, a tiny, icy object 4 billion miles away that looks to be shaped like a peanut or bowling pin.

Word of success came 10 hours after the middle-of-the-night encounter, once flight controllers in Maryland received word from the spacecraft late Tuesday morning. Cheers erupted at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory, home to Mission Control, as mission operations manager Alice Bowman declared: "We have a healthy spacecraft."

A huge spill-over crowd in a nearby auditorium joined in the loud celebration, cheering each green, or good, status update. Scientists and other team members embraced, while hundreds of others gave a standing ovation.

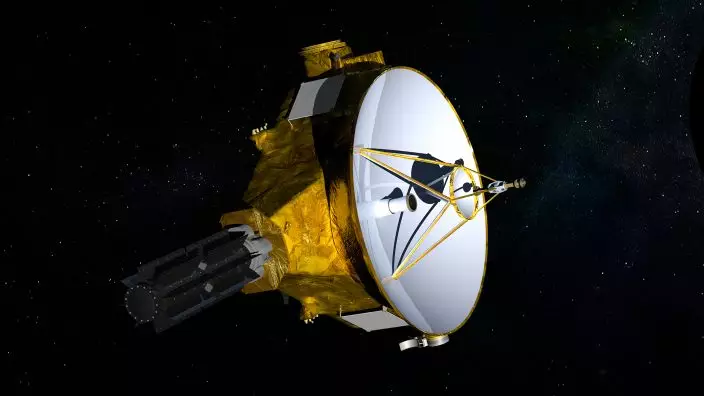

FILE - This illustration provided by NASA shows the New Horizons spacecraft. NASA launched the probe in 2006; it's about the size of a baby grand piano. NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is set to fly past the mysterious object nicknamed Ultima Thule at 12:33 a.m. Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019. (NASAJHUAPLSwRI via AP)

"I don't know about all of you, but I'm really liking this 2019 thing so far," lead scientist Alan Stern of Southwest Research Institute said to applause. "I'm here to tell you that last night, overnight, the United States spacecraft New Horizons conducted the farthest exploration in the history of humankind, and did so spectacularly."

New Horizons zoomed past the small celestial object known as Ultima Thule 3 ½ years after its spectacular brush with Pluto. Scientists said it will take nearly two years for New Horizons to beam back all its observations of Ultima Thule, a full billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) beyond Pluto. At that distance, it takes six hours for the radio signals to reach Earth.

Scientists did not want to interrupt observations as New Horizons swept past Ultima Thule — described as a bullet intersecting with another bullet — so they delayed radio transmissions. The spacecraft is believed to have come within 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) of Ultima Thule.

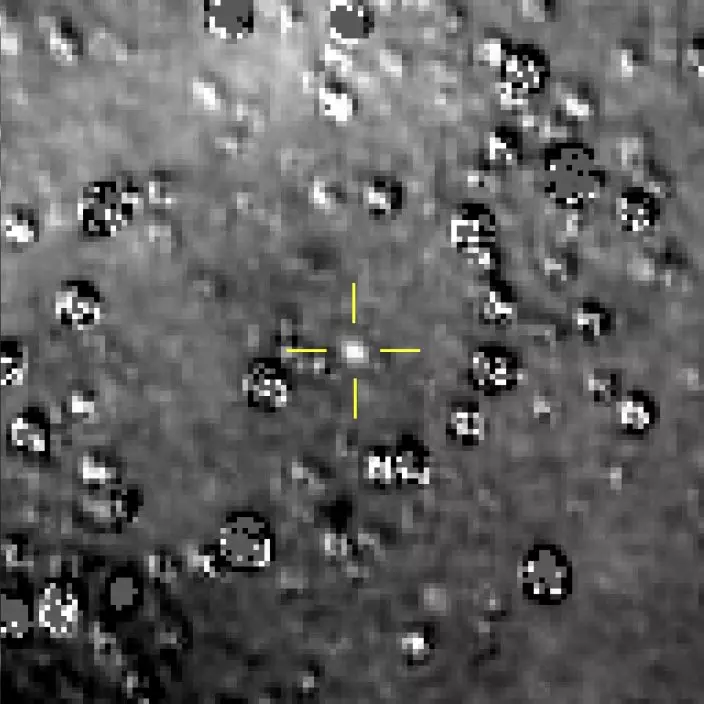

FILE - This composite image made available by NASA shows the Kuiper Belt object nicknamed "Ultima Thule," indicated by the crosshairs at center, with stars surrounding it on Aug. 16, 2018, made by the New Horizons spacecraft. The brightness of the stars was subtracted from the final image using a separate photo from September 2017, before the object itself could be detected. (NASAJohns Hopkins University Applied Physics LaboratorySouthwest Research Institute via AP)

Weary from dual countdowns late Monday and early Tuesday, the New Horizons team members were visibly anxious as they reassembled in late morning. "Happy New Year again," they bid one another. But the hundreds of spectators went wild nonetheless when the good news came in.

New Horizons' 2015 encounter with Pluto was the most distant exploration until Tuesday. The Ultima Thule rendezvous was more complicated, given its 4 billion-mile (6.4 billion-kilometer) distance from Earth, the much closer gap between the spacecraft and its target, and all the unknowns surrounding Ultima Thule.

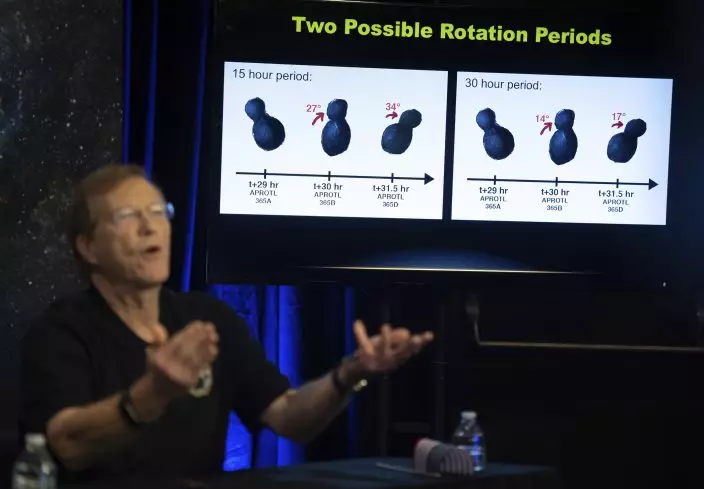

Based on rudimentary pictures snapped just hundreds of thousands of miles (kilometers) before the 12:33 a.m. close approach, Ultima Thule is decidedly elongated — about 22 miles by 9 miles (35 kilometers by 15 kilometers). Scientists say there are two possibilities: Ultima Thule is either one object with two connected lobes, sort of like a spinning bowling pin or peanut still in the shell, or two objects orbiting surprisingly close to one another. A single body is more likely, they noted. An answer should be forthcoming Wednesday, once new and better pictures arrive. The best color close-ups, though, won't be available until later in January and February.

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, left, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., left gives a high-five too New Horizons mission operations manager Alice Bowman, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), after the team received signals from the spacecraft that it is healthy and collected data, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019, at the Mission Operations Center at the APL in Laurel, Md. The spacecraft survived a journey to near the tiny, icy object called Ultima Thule, about 4 billion miles from Earth. (Bill IngallsNASA via AP)

The icy rock has been in a deep-freeze preservation state since the formation of our solar system 4.5 billion years ago. Scientists hope to learn about those origins through New Horizons' observations deep inside the so-called Kuiper Belt, or frozen Twilight Zone, on the fringes of the solar system.

New Horizons will continue to zoom farther away. The hope is that the mission, now totaling $800 million, will be extended yet again and another target will be forthcoming sometime in the 2020s.

Ultima Thule is the first destination to be reached that was not even known until after the spacecraft's launch. New Horizons rocketed from Cape Canaveral, Florida, in 2006.

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, center, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., celebrates with other mission team members after they received signals from the New Horizons spacecraft that it is healthy and collected data during the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019, at the Mission Operations Center at the APL in Laurel, Md. (Bill IngallsNASA via AP)

The Associated Press Health & Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Guests applaud New Horizons team members after the they received signals from the New Horizons spacecraft that it is healthy and it collected data during a fly-by of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019, at the Mission Operations Center at the APL in Laurel, Md. The spacecraft survived a journey to near the tiny, icy object called Ultima Thule, about 4 billion miles from Earth. (Bill IngallsNASA via AP)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks about new data received from the New Horizons spacecraft during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the spacecraft that it has completed a flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019, at the APL in Laurel, Md. The spacecraft survived the most distant exploration of another world, a tiny, icy object 4 billion miles away that looks to be shaped like a peanut or bowling pin. (Joel KowskyNASA via AP)

A new image of Ultima Thule, right, is displayed during a press conference after the New Horizons team received confirmation from the spacecraft has completed a flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019, at the APL in Laurel, Md. The spacecraft survived the most distant exploration of another world, a tiny, icy object 4 billion miles away that looks to be shaped like a peanut or bowling pin. From left are, New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, mission operations manager Alice Bowman, mission systems engineer Chris Hersman, and project scientist Hal Weaver. (Joel KowskyNASA via AP)

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, left, speaks about the New Horizons spacecraft during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the spacecraft that it has completed a flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019, at the Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md. Listening at right is mission operations manager Alice Bowman The spacecraft survived the most distant exploration of another world, a tiny, icy object 4 billion miles away that looks to be shaped like a peanut or bowling pin. (Joel KowskyNASA via AP)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, speaks about new data received from the New Horizons spacecraft during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the spacecraft that it has completed a flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019, at the APL in Laurel, Md. The spacecraft survived the most distant exploration of another world, a tiny, icy object 4 billion miles away that looks to be shaped like a peanut or bowling pin. (Joel KowskyNASA via AP)

New Horizons team members and guests watch a live feed of the Mission Operations Center (MOC) as the team waits to receive confirmation from the spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (Joel KowskyNASA via AP)