At the height of his power in 1971, Iran's Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi drew world leaders to a wind-swept luxury tent city, offering a lavish banquet of food flown in from Paris to celebrate 2,500 years of Persian monarchy in the ruins of Persepolis.

Only eight years later, his own empire would be in ruins.

Click to Gallery

FILE - In this Oct. 13, 1971 file photo, the Shah of Iran walks to the viewing stand of visiting dignitaries, at a ceremony to mark the 2,500 anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire, at Pasargadae, 49 miles northeast of Persepolis, Iran. At the height of his power in 1971, Pahlavi drew world leaders to a wind-swept luxury tent city in the ruins of Persepolis, offering a lavish banquet of food flown in from Paris for the celebration. (AP PhotoHorst Faas, File)

FILE - This Oct. 15, 1971 file photo, shows the interior of the banqueting tent during the celebrations to mark the 2,500 anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire, in Persepolis, Iran. At the height of his power in 1971, Iran’s Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi drew world leaders to the wind-swept luxury tent city, offering a lavish banquet of food flown in from Paris to celebrate in the ruins of Persepolis. Only eight years later, his own empire would be in ruins. (AP PhotoHorst Faas, File)

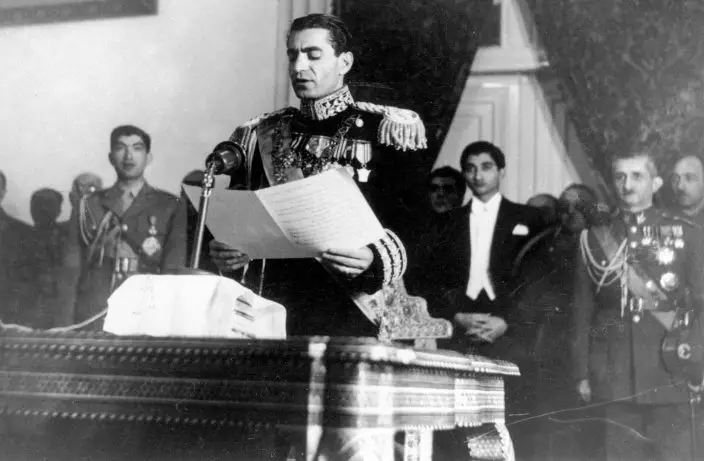

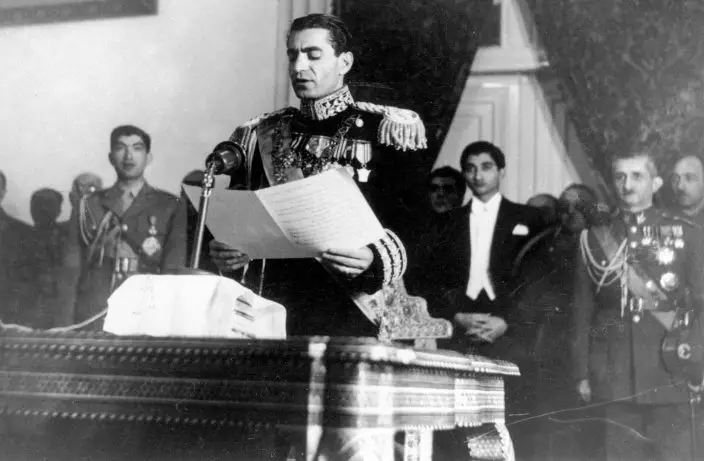

FILE - In this Feb. 16, 1950 file photograph, the Shah of Iran Mohammad Reza Pahlavi reads his inaugural speech at the initial session of his nation's first senate in Tehran, Iran. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this April 14, 1962 file photo, the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi sits between President John Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson as they look through binoculars of Marine landing operations at Camp LeJeuene, North Carolina. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this April 1, 1969 file photo, an unidentified U.S. Army officer salutes as the Shah of Iran Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, center, and President Richard Nixon, walk past, on the White House grounds in Washington. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. (AP Photo, File)

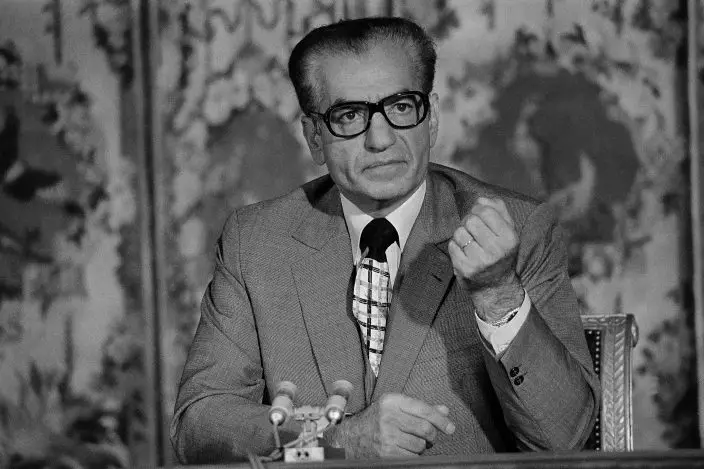

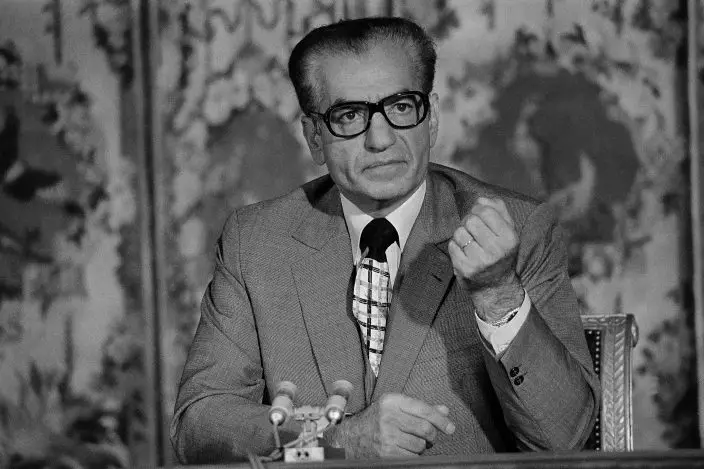

FILE - In this June 27, 1974 file photo, the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, gestures during a press conference at the Trianon in Versailles, near Paris, France. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. Instead of fighting and holding onto power, the shah instead chose exile 40 years ago, flying away on a jetliner that he himself piloted. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Dec. 31, 1977 file photograph, President Jimmy Carter toasts Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran during a New Year's Eve dinner at Niavaran Palace in Tehran, Iran. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 13, 1971 file photo, the Shah of Iran walks to the viewing stand of visiting dignitaries, at a ceremony to mark the 2,500 anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire, at Pasargadae, 49 miles northeast of Persepolis, Iran. At the height of his power in 1971, Pahlavi drew world leaders to a wind-swept luxury tent city in the ruins of Persepolis, offering a lavish banquet of food flown in from Paris for the celebration. (AP PhotoHorst Faas, File)

The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah's ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. While successfully riding rising oil prices in the 1970s, the shah failed to see that Iranians had begun to expect more as the country's people moved from the countryside to cities like Tehran.

FILE - This Oct. 15, 1971 file photo, shows the interior of the banqueting tent during the celebrations to mark the 2,500 anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire, in Persepolis, Iran. At the height of his power in 1971, Iran’s Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi drew world leaders to the wind-swept luxury tent city, offering a lavish banquet of food flown in from Paris to celebrate in the ruins of Persepolis. Only eight years later, his own empire would be in ruins. (AP PhotoHorst Faas, File)

And as the crisis reached a fever pitch, the shah's inability to act and poor decisions while secretly fighting what would be a fatal cancer doomed him.

"He was, as one diplomat said, almost Hamlet-like in his indecision," said Abbas Milani, a professor at Stanford University who wrote a book on the shah. "Shakespeare said sometimes greatness comes to the great, sometimes greatness is thrust upon them. And he had a kingdom thrust upon him."

Born in 1919, Mohammad Reza Shah was the son of Reza Shah, then an army officer. By 1925, Reza Shah became shah after forcing out the previous Qajar dynasty with the backing of the British. He named his nation Iran, which was still known as Persia until he ordered foreign diplomats to cease using the name.

FILE - In this Feb. 16, 1950 file photograph, the Shah of Iran Mohammad Reza Pahlavi reads his inaugural speech at the initial session of his nation's first senate in Tehran, Iran. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. (AP Photo, File)

But Iran's strong trade ties with Germany, Reza Shah's push for neutrality in World War II and Western fears over its oil supplies falling to the Nazis ultimately led to a Russian-British invasion of the country in 1941. Reza Shah abdicated in favor of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, at the insistence of the occupying British forces.

His full embrace of autocratic power came after the political chaos of 1953. Liberal Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh sought to nationalize Iran's oil industry. The British sought to keep their control of Iran's oilfields and its refinery at Abadan, then the world's biggest. Meanwhile, the U.S. feared Soviet influence expanding in Iran.

Out of these fears came TPAJAX, a CIA-backed coup plot to overthrow Mossadegh. Declassified U.S. documents show the CIA boasting that it had both leading security officials in its pocket, as well as hopes it could use the "powerfully influential clergy" within Shiite Iran to back the coup.

FILE - In this April 14, 1962 file photo, the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi sits between President John Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson as they look through binoculars of Marine landing operations at Camp LeJeuene, North Carolina. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. (AP Photo, File)

The Western plotters soon found one of their biggest problems to be the shah himself.

"His inability to take decisions coupled with his tendency to interfere in political life has on occasions been (a) disruptive influence," the U.S. Embassy in Tehran warned in February 1953. Ultimately, his twin sister, Princess Ashraf, and a U.S. general helped convince him to back the coup.

When the coup initially appeared to have failed, the shah fled to Baghdad and on to Italy. But protests supporting the shah, fanned in part by the CIA, led to Mosaddegh's fall and the monarch's return.

FILE - In this April 1, 1969 file photo, an unidentified U.S. Army officer salutes as the Shah of Iran Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, center, and President Richard Nixon, walk past, on the White House grounds in Washington. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. (AP Photo, File)

As time went on, monarchs in Egypt and Iraq fell to nationalistic army officers. The shah felt the pressure, growing increasingly suspicious of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and Iraq. He focused on the threats from abroad by pouring money into his military.

As Britain withdrew from the Middle East, the U.S. increasingly looked at the shah as a stabilizing force. He allowed U.S. and British spies to monitor the Soviet Union from secret bases in Iran. He also recognized Israel as a state in 1959, long before any Arab nation struck a peace deal.

Meanwhile, the shah reaped the benefit of skyrocketing global oil prices, which he himself had a hand in raising on his own and through Iran's membership in OPEC. He sought to industrialize and educate Iranians through his 1960s "White Revolution," as well as abolish the feudal state of much of its countryside.

FILE - In this June 27, 1974 file photo, the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, gestures during a press conference at the Trianon in Versailles, near Paris, France. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. Instead of fighting and holding onto power, the shah instead chose exile 40 years ago, flying away on a jetliner that he himself piloted. (AP Photo, File)

The land reforms angered Iran's gentry and saw the rural poor move to the cities. There, they would become fresh recruits for the revolution.

Shiite clerics railed against the shah's relationship with Israel, his acceptance of those of the Baha'i faith they viewed as heretics and the capital's raucous nightlife and sexual mores. They also opposed the shah granting suffrage to women as well as his opening of private universities, because the clerics had once had sole dominion over Iran's educational system.

Among those clergymen was Ruhollah Khomeini, a cleric who would be imprisoned and who would later go into exile. He would return as a triumphant ayatollah in 1979, riding the revolution to become Iran's first supreme leader.

FILE - In this Dec. 31, 1977 file photograph, President Jimmy Carter toasts Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran during a New Year's Eve dinner at Niavaran Palace in Tehran, Iran. The fall of the Peacock Throne and the rise of the Islamic Revolution in Iran grew out of the shah’s ever-tightening control over the country as other Middle East monarchies toppled. (AP Photo, File)

As the economy improved, the shah increasingly seized more and more power. Everything down to the minutiae of the state needed to pass his desk. And slowly, he lost control by trying to take all of it.

"He eliminated the center of Iranian politics, he certainly eliminated the left and he even eliminated much of the right and the only political force that was allowed to continue and expand . was the Islamists," Milani said. "He never saw where the threat came from. He wasn't alone. The CIA didn't. MI6 didn't."

Also hidden from view was his cancer. He had secretly taken chemotherapy for years but knew he had little time left. He took Valium and other medication as well, likely only adding to his indecisive nature.

FILE - In this Oct. 13, 1971 file photo, the Shah of Iran walks to the viewing stand of visiting dignitaries, at a ceremony to mark the 2,500 anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire, at Pasargadae, 49 miles northeast of Persepolis, Iran. At the height of his power in 1971, Pahlavi drew world leaders to a wind-swept luxury tent city in the ruins of Persepolis, offering a lavish banquet of food flown in from Paris for the celebration. (AP PhotoHorst Faas, File)

There had been a crackdown against political opponents, seeing thousands imprisoned and tortured by his feared SAVAK intelligence service. State media in Iran now typically refer to the shah as "despotic," focusing on the abuses and his lavish lifestyle.

Iran today, however, faces criticism from international human rights groups for arbitrary arrests, mistreatment and torture of prisoners. It is one of the world's top executioners, putting to death hundreds each year. It also has faced accusations that it detains people with Western ties and uses them as bargaining chips.

Instead of fighting and holding onto power, the shah instead chose exile 40 years ago, flying away on a jetliner that he himself piloted. He died in July 1980 at the age of 60, the last monarch Iran has ever known.

Asked in exile by interviewer David Frost if he wished he had "stayed and died fighting in the streets," the shah said no.

"If I was not a king, surely I would have done that," the shah said. "A crown, a throne could not be based on the not-too-very-solid foundation of blood."

Follow Jon Gambrell on Twitter at www.twitter.com/jongambrellap .

Five years ago, video images from a Minneapolis street showing a police officer kneeling on the neck of George Floyd as his life slipped away ignited a social movement.

Now, videos from another Minneapolis street showing the last moments of Renee Good's life are central to another debate about law enforcement in America. They've slipped out day by day since ICE agent Jonathan Ross shot Good last Wednesday in her maroon SUV. Yet compared to 2020, the story these pictures tell is murkier, subject to manipulation both within the image itself and the way it is interpreted.

This time, too, the Trump administration and its supporters went to work establishing their own public view of the event before the inevitable imagery appeared.

But half a decade later, so many things are not the same — from cultural attitudes to rapidly evolving technology around all kinds of imagery.

“We are in a different time,” said Francesca Dillman Carpentier, a University of North Carolina journalism professor and expert on the media's impact on audiences.

No one who saw the searing video of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin with his knee on Floyd's neck for more than nine minutes on May 25, 2020, is likely to forget it — and Chauvin's impassive face Floyd insisted he couldn't breathe. United in revulsion, demonstrators began one of the nation's largest-ever social movements. Chauvin was convicted of murder.

The footage “caused many individuals to experience an epiphany about racism, specifically cultural racism, in the United States,” legal scholar Angela Onwuachi-Willig wrote in a Houston Law Review study that examined whether white Americans experienced a collective cultural trauma.

She eventually concluded that didn't happen and that the impact diminished with time. The rollback of diversity programs with the second Trump administration offers evidence for her argument.

“The people who are writing the cultural narrative of the Good shooting took notes from the Floyd killing and are managing this narrative differently,” said Kelly McBride, an expert on media ethics for the Poynter Institute.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem labeled Good, who was demonstrating in opposition to ICE enforcement of immigration laws, a domestic terrorist — an interpretation that Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey dismissed with an expletive. Both President Donald Trump and Vice President JD Vance suggested the shooting was justified because Good was trying to run Ross down with her vehicle.

On the night of the killing, White House border czar Tom Homan was cautious in an interview with the “CBS Evening News” when anchor Tony Dokoupil showed him the most widely distributed video of the incident, taken by a bystander and posted by a reporter for the Minnesota Reformer. The veteran law enforcement official said it would be unprofessional for him to prejudge before an investigation.

Later that evening, Homan issued a statement calling the shooting “another example of the results of the hateful rhetoric and violent attacks” against U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Border Patrol officers.

Video of the incident has been generally inconclusive about whether Good's vehicle actually hit Ross before he opened fire. Even if she did, many experts question whether that represented grounds for firing his weapon. Clearly, however, that would bolster public sympathy for the officer.

“These ICE videos do present irrefutable facts — a woman drove her car and then she was shot dead by an ICE agent,” said Duy Linh Tu, a documentarian and professor at the Columbia University journalism school. “What the videos can't show is the intent of the woman or the officer. And that's the tricky part.”

Good, obviously, can’t speak to what motivated her to put her SUV in drive and move on Portland Avenue South.

Several news organizations have carefully examined the forensic evidence that has emerged. The Associated Press wrote that it was unclear if Good's car made contact with Ross. The Washington Post wrote that “videos examined by The Post, including one shared on Truth Social by Trump, do not clearly show whether the agent is struck or how close the front of the vehicle comes to striking him.”

The New York Times said that “in one video, it looks like the agent is being struck by the SUV. But when we synchronize it with the first clip, we can see the agent is not being run over.”

Video that emerged Friday from the Minnesota site Alpha News showed the incident from Ross' perspective. It, too, left many questions and no shortage of people willing to answer them.

Vance linked to the video online and wrote: “Many of you have been told this law enforcement officer wasn't hit by a car, wasn't being harassed and murdered an innocent woman. The reality is that his life was endangered and he fired in self-defense.”

Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer wrote online that “how could anyone on the planet watch this video and conclude what JD Vance says?” Schumer said the administration “is lying to you.”

When one online commentator wrote that Good did not deserve to be shot in the face, conservative media figure Megyn Kelly responded, “Yes, she did. She hit and almost ran over a cop.”

Poynter’s McBride said the media has generally done a good and careful job outlining the evidence that is circulating around in the public. But the administration has also been effective in spreading its interpretation, she said.

There are more camera angles available now than there was with Floyd, but “I don't know if that adds clarity or more fog to this case,” Tu said. “I think that people will see what they want to see. Or, rather, they'll pick the angle that aligns with what they already believe.”

That nagging sense of uncertainty left by the videos leaves experts like Tu and Carpentier to conclude they will pale in impact compared to the Floyd case. With each passing year, the public is becoming more desensitized to images of violence — as the online spread of footage showing Republican activist Charlie Kirk illustrated, she said.

The spread of AI-enhanced fake images is also teaching the public to question what it sees, she said. Before Ross was identified, BBC Verify said false images were being spread online speculating about what the masked agent looked like, and fake video of a Minneapolis demonstration spread.

“Now you can't believe what you're seeing,” Carpentier said. “You don't know if what you're seeing is the real video or if it has been doctored. I don't think AI is being a friend in this case at all.”

David Bauder writes about the intersection of media and entertainment for the AP. Follow him at http://x.com/dbauder and https://bsky.app/profile/dbauder.bsky.social.

Federal immigration officers make an arrest as bystanders film the incident Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/John Locher)

Bystanders film a federal immigration officer in their car Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/John Locher)