Bundled up against the icy cold and drifting snow, Don Olson has tended the trail of a popular cross country ski race in Minnesota for years.

Fixing problem spots on the Vasaloppet's route often meant braving the freezing temperatures and frigid winds that have always defined this state. But recently, things have changed: Instead of plodding through the snow, Olson and other volunteers had to start making it.

Click to Gallery

Bundled up against the icy cold and drifting snow, Don Olson has tended the trail of a popular cross country ski race in Minnesota for years.

Winter just isn't the same in Minnesota these days. And as the latest season ends, residents say their lifestyles are changing with it.

Longtime residents who enjoy winter sports and activities have done their best to adjust, but it's not always easy.

Grousing about the weather is regular conversation in the state, but plenty of Minnesotans actually love winter and say it's part of their identity. Many are concerned that the season is not what it used to be.

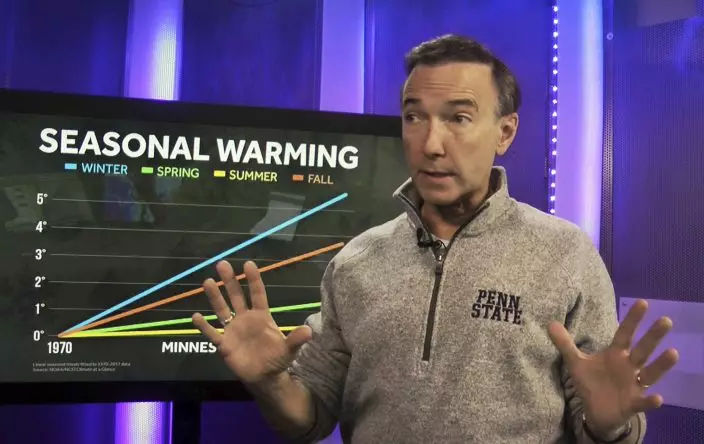

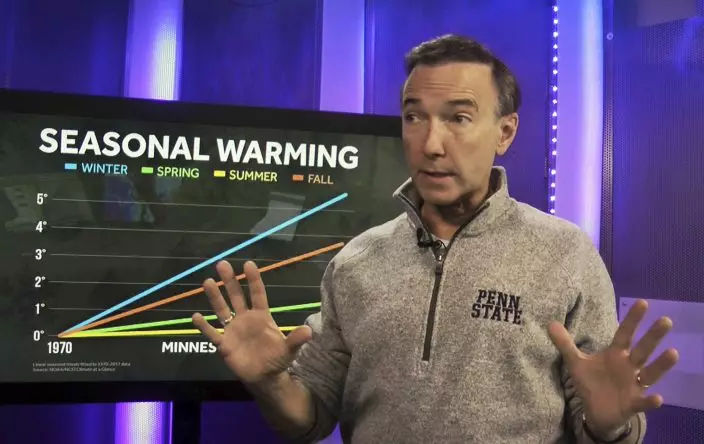

But overall, winter is warming fast — by more than 5 degrees since 1970. Alaska and Vermont have also seen winters warm by more than 5 degrees, according to NOAA data.

"We just simply don't get consistent snow anymore," Olson said. "In order to survive, we felt like we needed to do this."

In this Feb. 23, 2019 photo, Paul Riemer of Eden Prairie, Minn., fishes through a hole in the ice of Lake Minnetonka in Wayzata, Minn. Since 1970, Minnesota's winters have been warming at a rate of more than 1 degree a decade. The change is noticeable to many who enjoy outdoor winter activities, allowing fewer opportunities for cross-country ski races, snowmobiling, dog sledding, ice fishing and outdoor skating. (AP PhotoJeff Baenen)

Winter just isn't the same in Minnesota these days. And as the latest season ends, residents say their lifestyles are changing with it.

Minnesota is among the fastest warming states, and Minnesota's winters are warming faster than its other seasons. Data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration show that since 1970, Minnesota's winters have warmed at an average rate of 1.1 degrees per decade — that's more than five times faster than the rate of winter warming in previous years.

"We've lost some of our winter weather mojo," said longtime meteorologist Paul Douglas. "Maybe one in four winters now, today, are old-fashioned pioneer winters, where we really get socked with cold and snow. The other 70, 75 percent of the winters are trending milder."

In this Feb. 23, 2019 photo, a snowmobile sits on the snow-covered ice of Lake Minnetonka in Wayzata, Minn., while ice anglers gather in the background. Since 1970, Minnesota's winters have been warming at a rate of more than 1 degree a decade. The change is noticeable to many who enjoy outdoor winter activities, allowing fewer opportunities for cross-country ski races, snowmobiling, dog sledding, ice fishing and outdoor skating. (AP PhotoJeff Baenen)

Longtime residents who enjoy winter sports and activities have done their best to adjust, but it's not always easy.

During mild spells, some sled dog races have been shortened or canceled. Snowmobilers say they've traveled greater distances to find good snow. Outdoor skating rinks and ponds have sometimes been too soft or slushy to use. And businesses that cater to ice anglers or other winter enthusiasts can see a slowdown.

Even Minnesota's beloved moose have felt the effects, with parasites that don't die off in milder temperatures a leading cause of moose deaths, according to a state study.

In this Feb. 23, 2019 photo, Jason Kong uses an auger to drill holes in Lake Minnetonka in Wayzata, Minn., as he prepares to go ice fishing. Since 1970, Minnesota's winters have been warming at a rate of more than 1 degree a decade. State residents notice the change, and say winter isn't as cold as it used to be and the snow is less predictable. (AP PhotoJeff Baenen)

Grousing about the weather is regular conversation in the state, but plenty of Minnesotans actually love winter and say it's part of their identity. Many are concerned that the season is not what it used to be.

"We'd like to go back to the nostalgia of just having cold weather. Grab a scarf and hot chocolate and enjoy it," said Jim Dahline of the U.S. Pond Hockey Championships, an amateur tournament that in 2016 began starting two weeks later to increase its chances for skateable ice.

To be sure, Minnesota still gets cold. Minneapolis-St. Paul just endured its snowiest February ever — 39 inches. The polar vortex in January, and a similar event in 2014, brought the state some of its coldest weather in years.

In this Feb. 14, 2019 photo, cross-country skiers practice at Theodore Wirth Regional Park in Golden Valley, Minn. Since 1970, Minnesota's winters have been warming at a rate of more than 1 degree a decade. The change is noticeable to many who enjoy outdoor winter activities, allowing fewer opportunities for cross-country ski races, snowmobiling, dog sledding, ice fishing and outdoor skating. (AP PhotoJeff Baenen)

But overall, winter is warming fast — by more than 5 degrees since 1970. Alaska and Vermont have also seen winters warm by more than 5 degrees, according to NOAA data.

Minnesota's winter season has gotten shorter since 1970, too, with an average of 16 fewer days from the first frost to the last, and about 12 days less of ice cover on the state's lakes.

The winter season is warming faster than other seasons because greenhouse gases are trapping heat in the atmosphere at a time when the earth is supposed to be cooling, said Kenny Blumenfeld, senior climatologist for the Department of Natural Resources. While Minnesota has been warming over the last century, the trend has been concentrated since 1970.

In this Feb. 21, 2019 photo, meteorologist Paul Douglas, shown in his Eden Prairie, Minn. studio, says Minnesota has "lost some of our winter weather mojo." Minnesota winters have gotten warmer since 1970. State residents notice the change, and say winter isn't as cold as it used to be and the snow is less predictable. (AP PhotoJeff Baenen)

The changes are felt by many.

Musher Frank Moe loves running his sled dogs on cold winter nights under the stars, when the air is crisp and everything is quiet.

But there are fewer opportunities now because of patchy snow. He's seen several local races that once brought tourism dollars to smaller northern Minnesota cities get canceled for good.

"When a local race gets canceled and you don't have mushing conditions, you'll either quit ... or you'll move to some place where you think will have more predictable snow and weather," Moe said.

That's what Moe did. A decade ago, he and his wife moved 250 miles from Bemidji in north central Minnesota to the north shore of Lake Superior to increase their chances of reliable snow.

"It's dramatic and everybody knows it," Moe said of the change in Minnesota winters. "I don't think there's any climate change deniers in the musher world."

No one has tallied the economic impact but milder winters take a toll on some businesses.

Steve Crumley, a snowmobiler who loves traveling the state with the Eden Prairie Snowdrifters club, said his group canceled several trips because of poor conditions.

"I certainly have noticed in the last five years we have to go further to find the good snow," Crumley said.

Olson, the Vasaloppet race volunteer, said he's worried about what's in store in the years ahead.

"I don't look forward to the day when our Minnesota winters are like Missouri or southern Iowa, or Nebraska — where you get snow one day and the next day it's all mud," he said.

Associated Press writers Doug Glass in Minneapolis and Blake Nicholson in Bismarck, North Dakota, contributed to this story.

Follow Amy Forliti on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/amyforliti

DUMA, West Bank (AP) — Charred homes and cars dotting this hilltop village surrounded by olive groves are a searing reminder of Palestinians' vulnerability to rising violence from Israeli settlers.

The trail of wreckage along Duma's main road is the aftermath of a three-hour attack in mid-April that left 15 homes damaged by arson and six residents injured by bullets, the head of its village council said. It was one of nearly 800 settler attacks against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank since Hamas attacked Israel from the Gaza Strip on Oct. 7, according to the U.N.

The burnt remains in Duma also highlight the village's limited resources to clean up and rebuild, let alone defend itself from future incursions, which seem inevitable as gun-toting settlers patrol the area roughly 20 miles (30 kilometers) north of Jerusalem.

“We as the village of Duma ... do not have the power to defend ourselves,” said Suleiman Dawabsha, chairman of the village council for this community of more than 2,000 people. He estimated the attack caused five million shekels ($1.3 million) in damage.

The rampage on April 13 echoed a similar event that took place almost a decade ago. In 2015, three Palestinians from Duma were killed, including an 18 month-old baby, after settlers fire-bombed a home there. An Israeli man was later convicted for murder.

The latest attack against Duma was part of a wave of settler violence touched off by the death of a 14-year-old Israeli who went missing on the morning of April 12. Authorities found his body the next day and they have arrested a man from Duma who they say was connected to the boy's alleged murder.

On April 15, two days after the attack in Duma, two Palestinians were shot dead by settlers near the town of Aqraba, according to the Palestinian Health Ministry. And in a related spurt of violence, a man was killed by Israeli fire on April 12 in nearby al-Mughayyir, though it remains unclear whether the fatal bullet was fired by a soldier or settler.

There have been 794 settler attacks against Palestinians in the West Bank since Oct. 7 — from stones thrown at passing cars to bullets fired at residents, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. At least 10 Palestinians have been killed by settlers in these attacks, it said.

Attacks by settlers aren't the only form of violence on the rise in the West Bank.

Since the war in Gaza began, nearly 500 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli fire in the territory, according to the Health Ministry based in Ramallah, which says the overwhelming majority have been shot dead by soldiers. Palestinians in the West Bank have killed nine Israelis, including five soldiers, since Oct. 7, according to U.N. data.

The war has undoubtedly heightened tensions between settlers and Palestinians. But Israeli human rights groups blame the far-right government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for fueling settler violence by promoting an ideology of total Israeli supremacy in the West Bank.

These groups say the Israeli army doesn't do enough to stop the violence, and even facilitates it in some cases by offering the settlers protection. The Israeli army said in a statement it tries to protect everyone living in the West Bank and that complaints about soldiers are investigated.

No one was killed in the attack on Duma, but residents described narrow escapes.

Ibrahim Dawabsha, a truck driver and father of four, said most of his family hid in the kitchen as settlers launched firebombs and set part of their home ablaze.

“My daughter was at her uncle’s house, there was no one there,” he said. “What they (might) do to her I don’t know.”

The heads of Duma and al-Mughayyir said Israeli troops arrived shortly after the attacks on their communities began but did little to intervene. Instead, they fired at Palestinians attempting to confront the settlers, these officials said.

A prominent Israeli human rights group, Yesh Din, described it as an “umbrella of security” — a collaboration it says has become increasingly common since Israel's right-wing coalition government came to power in late 2022.

“As soon as the Palestinians try to protect themselves, they’re the ones who the army attacks,” said Ziv Stahl, Yesh Din’s director.

The United States has increased pressure on Israel to curb settler attacks in the West Bank, sanctioning some leaders, including a close ally of Israel's far-right national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir.

Dawabsha, the chief of Duma, does not believe the pressure campaign will be effective. “I am not pinning my hopes on the American government,” he said.

Israel captured the West Bank, east Jerusalem and Gaza in the 1967 Mideast war, territories Palestinians want as part of a future state. Settlers claim the West Bank, home to some 3 million Palestinians, is their biblical birthright.

Around 500,000 Israeli settlers live across hundreds of settlements and outposts in the West Bank. These segregated and tightly guarded communities vary in size and nature. Larger settlements are akin to Jerusalem’s sprawling suburbs, while smaller unauthorized outposts can consist of just a few caravans parked on a hilltop.

Outposts often receive tacit government support and sometimes they gain formal recognition — and receive funding — from the Israeli government.

Duma's geography makes it uniquely vulnerable to attack.

Overlooking Jordan and Israeli settlements to the east, the village is surrounded more closely by at least three outposts that the head of its council says have expanded gradually over the past decade. Duma is in a section of the West Bank known as Area B: Its civil affairs are governed by the Palestinian Authority, but the Israeli military is in charge of its security.

Palestinians largely consider the PA to be ineffective and corrupt, and it rarely opposes Israel's military operations in the territory.

Over the past year, settlers have cut off Duma's access to four vital springs and wells that surround the village by sabotaging roads and other infrastructure, according to residents.

In the days following Hamas' Oct. 7 attack on southern Israel, more than 100 Bedouin Arabs that were living a nomadic lifestyle in the pastures south of Duma relocated to its fringes in search of greater safety and resources.

One of them, Ali Zawahiri, said his extended family relocated after settlers had begun burning their tents and stealing their livestock in apparent revenge attacks. The Bedouin Arabs living near Duma are one of 16 such communities in the West Bank that have relocated because of settler violence or threats since the start of 2023, according to Yesh Din.

"He is armed with a gun and I am just a person with nothing,” Zawahiri said.

An armed unit run by the Palestinian Authority that formerly patrolled the perimeter of West Bank towns at night halted operations shortly after the Gaza war broke out, when members of the force were kidnapped by settlers.

When asked how they might better defend themselves in the future, residents of Duma struggled to answer.

“What preparations?" said Ibrahim Dawabsha, whose truck — his main source of income — was burnt to ashes. "There are no preparations.”

Associated Press video journalist Imad Isseid contributed to this report.

This story has been corrected to show that some 3 million Palestinians live in the West Bank. An earlier version said there were 2,000.

Follow AP's coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/israel-hamas-war

Bedouin Khaled Arara, 54, and his son Ali, 7, pose for a picture on the road leading to his hamlet that was closed with rocks by Israeli settlers, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

A Bedouin man attends his herd after he fled his home following a wave of attacks by Israeli settlers, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

An Israeli settlers' outpost on a hilltop, right, is seen from outskirts of the West Bank town of Duma, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

Bedouins fled their homes on the far hillside seen in the background following a wave of attacks by Israeli settlers, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

Bedouins fled their homes on the far hillside seen in the background following a wave of attacks by Israeli settlers, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

A Bedouin man fled his home on the far hillside seen in the background following a wave of attacks by Israeli settlers, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

Ibrahim Dawabsha, 34, holds hands with his daughter Ghena, 3 while posing for a picture in front of his truck, at the garage of the family house, that was torched during an attack by Israel settlers last month, in the West Bank village of Duma, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

Fathi Dawabsha, 82, walks toward the remains of a family vehicle that was torched during an attack by Israel settlers last month, in the West Bank village of Duma, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

Fatahi Mohammad, 20, walks past his family's truck that was torched during an attack by Israel settlers last month, in the West Bank village of Duma, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

Fatahi Dawabsha, 82, walks past his family's vehicles that were torched during an attack by Israel settlers last month, in the West Bank village of Duma, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

House and vehicles of Ibrahim Dawabsha and his family that were torched during an attack by Israel settlers last month, in the West Bank village of Duma, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

House and vehicles of Ibrahim Dawabsha and his family that were torched during an attack by Israel settlers last month, in the West Bank village of Duma, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)