In the world of autonomous vehicles, Pittsburgh, Phoenix and Silicon Valley are bustling hubs of development and testing. But ask those involved in self-driving vehicles when we might actually see them carrying passengers in every city, and you'll get an almost universal answer: Not anytime soon.

An optimistic assessment is 10 years. Many others say decades as researchers try to conquer a number of obstacles.

Click to Gallery

In the world of autonomous vehicles, Pittsburgh, Phoenix and Silicon Valley are bustling hubs of development and testing. But ask those involved in self-driving vehicles when we might actually see them carrying passengers in every city, and you'll get an almost universal answer: Not anytime soon.

Here are the problems that researchers must overcome to start giving rides without humans behind the wheel:

Heavy snow, rain, fog and sandstorms can obstruct the view of cameras. Light beams sent out by laser sensors can bounce off snowflakes and think they are obstacles. Radar can see through the weather, but it doesn't show the shape of an object needed for computers to figure out what it is.

But many companies are still trying to master the difficult task of driving on a clear day with steady traction.

That makes Tesla's declarations that it will offer fully autonomous vehicles by the second quarter of next year all the more striking. The company announced its ambitious plans during an investor conference on Monday. But skeptics doubt that Tesla can pull it off.

In this Jan. 4, 2019, photo made with a slow shutter speed, one of the test vehicles from Argo AI, Ford's autonomous vehicle unit, navigates through the strip district near the company offices in Pittsburgh. The people developing self-driving vehicles say it could be anywhere from 10 years to decades before the cars will be carrying passengers in every city. Researchers are trying to conquer a number of obstacles. (AP PhotoKeith Srakocic)

Here are the problems that researchers must overcome to start giving rides without humans behind the wheel:

SNOW AND WEATHER

When it's heavy enough to cover the pavement, snow blocks the view of lane lines that vehicle cameras use to find their way. Researchers so far haven't figured out a way around this. That's why much of the testing is done in warm-weather climates such as Arizona and California.

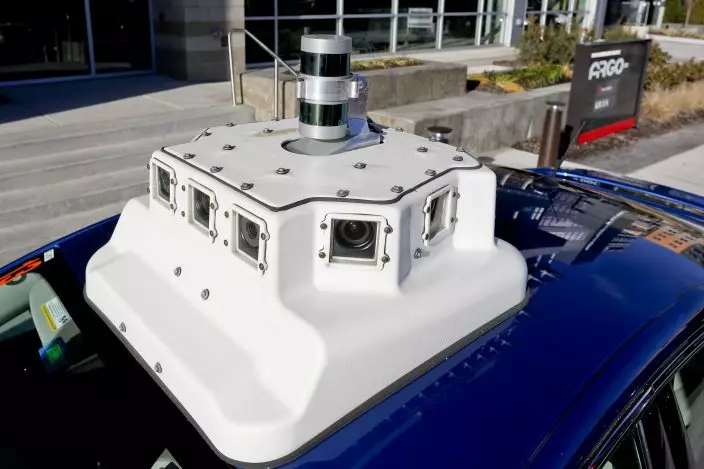

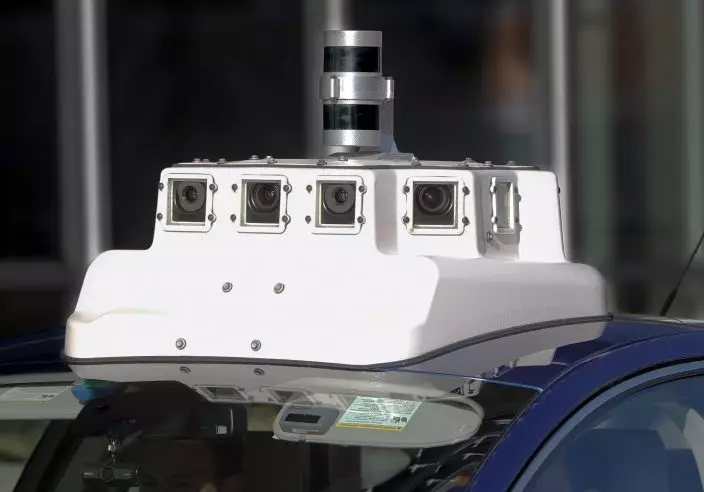

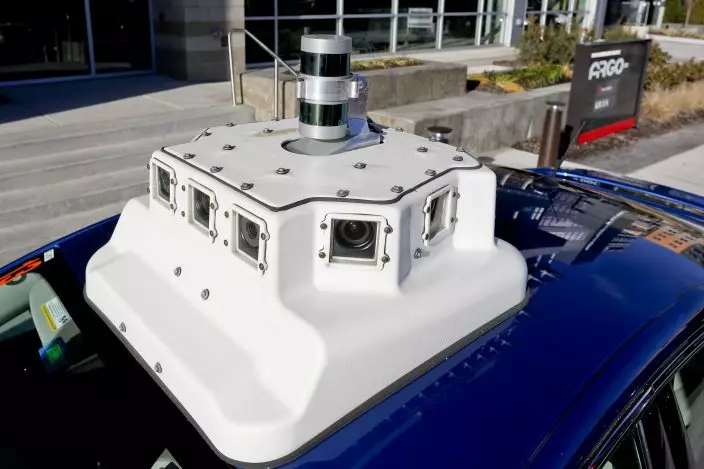

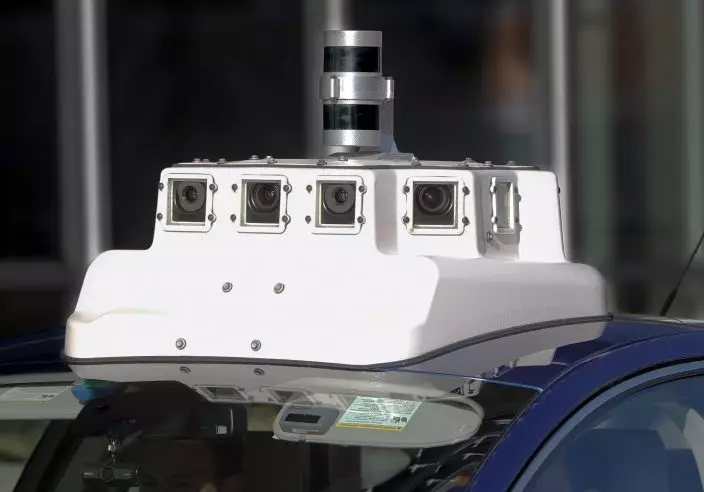

In this Dec. 18, 2018, photo, a sensor and camera array on top of one of the test vehicles from Argo AI, Ford's autonomous vehicle unit, is parked at the company offices in Pittsburgh. In the world of autonomous vehicles, Pittsburgh, Phoenix and Silicon Valley are bustling hubs of development and testing. But ask those involved in self-driving vehicles when we might actually see them carrying passengers in every city, and you'll get an almost universal answer: Not anytime soon. An optimistic assessment is 10 years. Many others say decades as researchers try to conquer a number of obstacles. (AP PhotoKeith Srakocic)

Heavy snow, rain, fog and sandstorms can obstruct the view of cameras. Light beams sent out by laser sensors can bounce off snowflakes and think they are obstacles. Radar can see through the weather, but it doesn't show the shape of an object needed for computers to figure out what it is.

"It's like losing part of your vision," says Raj Rajkumar, an electrical and computer engineering professor at Carnegie Mellon University.

Researchers are working on laser sensors that use a different light beam wavelength to see through snowflakes, said Greg McGuire, director of the MCity autonomous vehicle testing lab at the University of Michigan. Software also is being developed so vehicles can differentiate between real obstacles and snowflakes, rain, fog, and other conditions.

In this Dec. 18, 2018, photo, one of the test vehicles from Argo AI, Ford's autonomous vehicle unit, navigates through the strip district near the company offices in Pittsburgh. In the world of autonomous vehicles, Pittsburgh, Phoenix and Silicon Valley are bustling hubs of development and testing. But ask those involved in self-driving vehicles when we might actually see them carrying passengers in every city, and you'll get an almost universal answer: Not anytime soon. An optimistic assessment is 10 years. Many others say decades as researchers try to conquer a number of obstacles. (AP PhotoKeith Srakocic)

But many companies are still trying to master the difficult task of driving on a clear day with steady traction.

"Once we are able to have a system reliably perform in those, then we'll start working toward expanding to those more challenging conditions," said Noah Zych, Uber's head of system safety for self-driving cars.

In some limited areas that have been mapped in three dimensions, the cars can function in light snow and rain.

This Dec. 18, 2018, photo shows a sensor and camera array on top of one of the test vehicles from Argo AI, Ford's autonomous vehicle unit, at the company offices in Pittsburgh. In the world of autonomous vehicles, Pittsburgh, Phoenix and Silicon Valley are bustling hubs of development and testing. But ask those involved in self-driving vehicles when we might actually see them carrying passengers in every city, and you'll get an almost universal answer: Not anytime soon. An optimistic assessment is 10 years. Many others say decades as researchers try to conquer a number of obstacles. (AP PhotoKeith Srakocic)

PAVEMENT LINES AND CURBS

Across the globe, roadway marking lines are different, or they may not even exist. Lane lines aren't standardized, so vehicles have to learn how to drive differently in each city. Sometimes there aren't any curbs to help vehicles judge lane width.

For instance, in Pittsburgh's industrial "Strip District," where many self-driving vehicles are tested, the city draws lines across the narrow lanes to mark where vehicles should stop for stop signs. Sometimes the lines are so far back and buildings are so close to the street that autonomous cars can't see traffic on the cross street if they stop at the line. One workaround is to program vehicles to stop for the line and creep forward.

In this Dec. 18, 2018, photo, a sensor and camera array on top of one of the test vehicles from Argo AI, Ford's autonomous vehicle unit, is parked at the company offices in Pittsburgh. The people developing self-driving vehicles say it could be anywhere from 10 years to decades before the cars will be carrying passengers in every city. Researchers are trying to conquer a number of obstacles. (AP PhotoKeith Srakocic)

"Is it better to do a double stop?" asked Pete Rander, president of Argo AI, an autonomous vehicle company in which Ford has invested heavily. "Since intersections vary, it's not that easy."

DEALING WITH HUMAN DRIVERS

For many years, autonomous vehicles will have to deal with humans who don't always play by the rules. They double-park or walk in front of cars. Recently in Pittsburgh, an Argo backup driver had to take over when his car stopped during a right turn, blocking an intersection when it couldn't immediately decide whether to go around a double-parked delivery truck.

"Even if the car might eventually figure something out, it's shared space, and it's socially unacceptable" to block traffic, Rander said.

Humans also make eye contact with other drivers to make sure they're looking in the right direction, something still being developed for autonomous vehicles.

Add to that the antagonism that some feel toward robots. People have reportedly been harassing Waymo's autonomous test vehicles near Phoenix. The Arizona Republic reported in December that police is suburban Chandler have documented at least 21 cases in the past two years, including a man waiving a gun at a Waymo van and people who slashed tires and threw rocks. One Jeep forced the vans off the road six times.

LEFT TURNS

Deciding when to turn left in front of oncoming traffic without a green arrow is one of the more difficult tasks for human drivers and one that causes many crashes. Autonomous vehicles have the same trouble.

Waymo CEO John Krafcik said in an interview last year that his company's vehicles are still encountering occasional problems at intersections.

"I think the things that humans have challenges with, we're challenged with as well," he said. "So sometimes unprotected lefts are super challenging for a human, sometimes they're super challenging for us."

CONSUMER ACCEPTANCE

The fatal Uber crash near Phoenix last year did more than push the pause button on testing. It also rattled consumers who someday will be asked to ride in self-driving vehicles.

Surveys taken after the Uber crash showed that drivers are reluctant to give up control to a computer. One by AAA in March found 71 percent of people are afraid to ride in fully self-driving vehicles.

Autonomous vehicle companies are showing test passengers information on screens about where the vehicles are headed and what its sensors are seeing. The more people ride, the more they trust the vehicles, says Waymo's Krafcik.

"After they become more and more confident they rarely look at the screens, and they're on their phones or relaxing or sleeping," he said.

PARIS (AP) —

Reuters photographer Mohammed Salem captured this year’s prestigious World Press Photo of the Year award Thursday with a depiction of loss and sorrow in Gaza, a heartrending photo of a Palestinian woman cradling the body of her young niece. The photograph, taken in Khan Younis just days after Salem’s own child was born, shows 36-year-old Inas Abu Maamar holding five-year-old Saly, who was killed along with her mother and sister when an Israeli missile struck their home.

Salem, who is Palestinian, described this photo filed Nov. 2 last year, as a “powerful and sad moment that sums up the broader sense of what was happening in the Gaza Strip.”

The image ”truly encapsulates this sense of impact,” said global jury chair Fiona Shields, The Guardian newspaper's head of photography. “It is incredibly moving to view and at the same time an argument for peace, which is extremely powerful when peace can sometimes feel like an unlikely fantasy,” she added.

The World Press Photo jury praised the shot’s sense of care and respect and its offering of a “metaphorical and literal glimpse into unimaginable loss.”

This is not the first time Salem has been recognized for his work on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; he received a World Press Photo award more than a decade ago for another depiction of the human toll of conflict in the Gaza strip.

In the three other global categories announced Thursday, South Africa’s Lee-Ann Olwage won Photo Story of the Year for her touching series “Valim-babena,” featured in GEO magazine. The project focused on the stigmatization of dementia in Madagascar, a topic she explored through intimate portraits of “Dada Paul” and his family. Lack of public awareness surrounding dementia means that people displaying symptoms of memory loss are often stigmatized.

In the series, “Dada Paul,” who has lived with dementia for 11 years, is tenderly cared for by his daughter Fara. One of the standout images in the series shows him preparing for church with his granddaughter Odliatemix, capturing moments of normalcy and warmth amidst the challenges of dementia.

Photographer Alejandro Cegarra, a Venezuelan native who migrated to Mexico in 2017, won the Long-Term Project award for “The Two Walls,” published by The New York Times and Bloomberg. Cegarra’s project, initiated in 2018, examines a shift in Mexico’s immigration policies, which have moved from being historically open to enforcing strict regulations at its southern border. The jury said the photographer's perspective as a migrant gave it a “sensitive," human-centered perspective, according to a press release.

Julia Kochetova of Ukraine won the Open Format award for “War Is Personal.” The project stood out from coverage of the ongoing conflict by offering a personal look at the harsh realities of war. On a dedicated website, she merged traditional photojournalism with a diary-like documentary style, incorporating photography, poetry, audio clips and music.

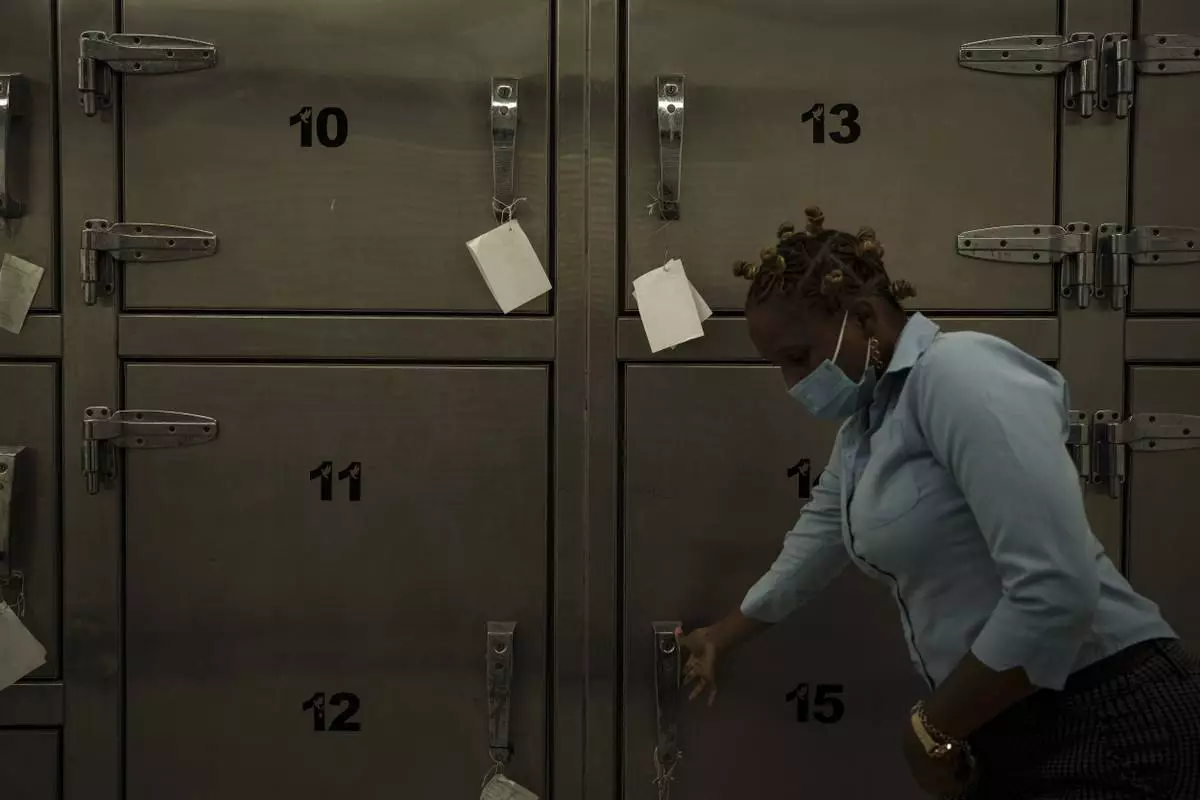

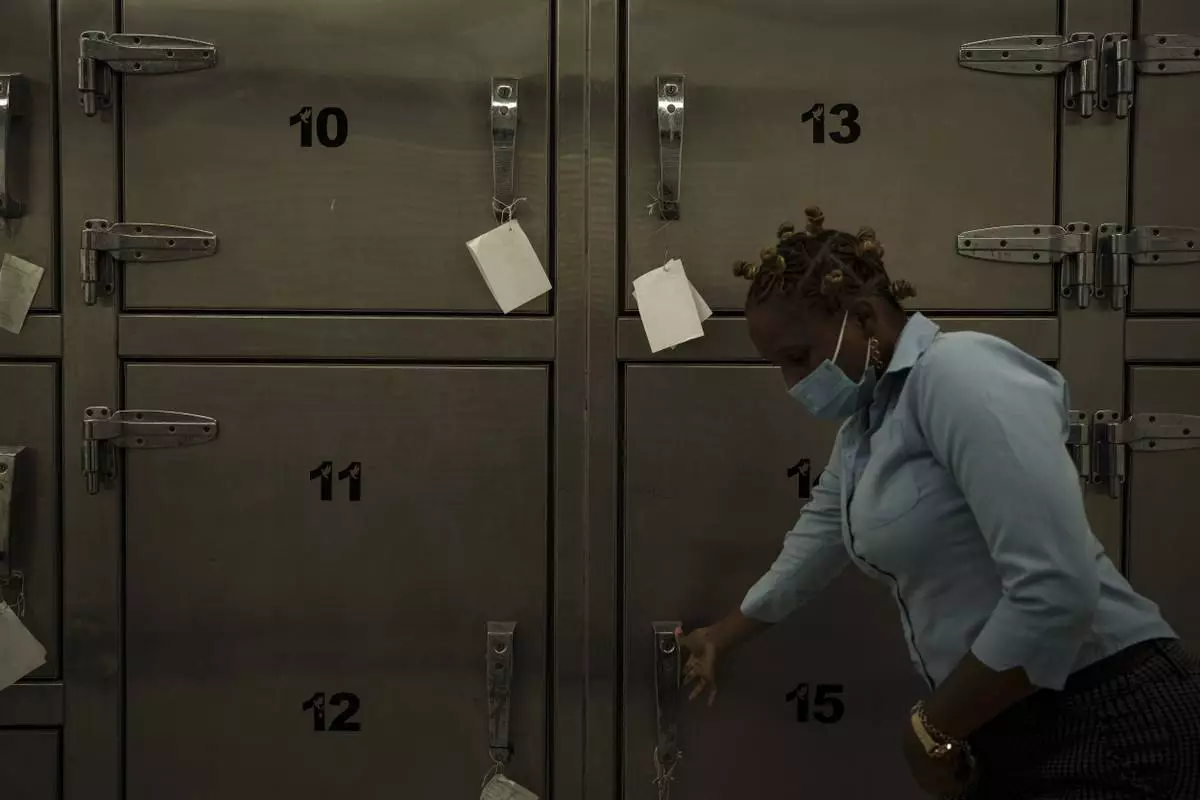

The Associated Press won the Open Format award in the regional Africa category with the multimedia story “Adrift,” created by journalists Renata Brito and Felipe Dana. The story investigates the fate of West African migrants who attempted to reach Europe via a treacherous Atlantic route but ended up on a ghost ship discovered off Tobago. The team’s compelling use of photography, cinematography and detailed narrative, enhanced by expert design and multimedia elements, highlights the perils faced by migrants and the human stories behind global migration issues.

The Associated Press' Ebrahim Noroozi won the Asia Stories award for his series “Afghanistan on the Edge,” which documents the country since the Taliban took over in August 2021.

World Press Photo is an independent, nonprofit organization based in the Netherlands, founded in 1955.

This image provided by World Press Photo is part of a series titled Afghanistan on the Edge by Ebrahim Noroozi, Associated Press, which won the World Press Photo Asia Series category and showsAn Afghan refugee rests in the desert next to a camp near the Torkham Pakistan-Afghanistan border, in Torkham, Afghanistan, Friday, Nov. 17, 2023. A huge number of Afghans refugees entered the Torkham border to return home hours before the expiration of a Pakistani government deadline for those who are in the country illegally to leave or face deportation. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

This image provided by World Press Photo is part of a series titled Afghanistan on the Edge by Ebrahim Noroozi, Associated Press, which won the World Press Photo Asia Series category and shows : Since the chaotic Taliban takeover of Kabul on Aug. 15, 2021, an already war-devastated economy once kept alive by international donations alone is now on the verge of collapse. There isn't enough money for hospitals. The World Health Organization is warning of millions of children suffering malnutrition, and the U.N. says 97% of Afghans will soon be living below the poverty line. Three Afghan internally displaced children look with surprise at an apple that their mother brought home after begging, in a camp on the outskirts of Kabul, Afghanistan, Thursday, Feb 2, 2023. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

This image provided by World Press Photo is part of a multimedia project by Associated Press' Renata Brito and Felipe Dana titled Adrift, won the World Press Photo Africa Regional Winner Open Format category and shows a mortuary technician opening the door of a refrigerator used to store the remains of migrants recovered from inside the Mauritania boat that appeared drifting near the island of Tobago, in Scarborough, Trinidad and Tobago, Tuesday, Jan. 25, 2022. In May 2021 a boat from Mauritania full of dead men was found off the coast of the Caribbean Island of Tobago. Who were these men and why were they on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean? Two visual journalists sought answers, uncovering a story about migrants from West Africa who seek opportunity in Europe via an increasingly popular but treacherous Atlantic route. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

This image provided by World Press Photo is part of a multimedia project by Associated Press' Renata Brito and Felipe Dana titled Adrift, won the World Press Photo Africa Regional Winner Open Format category and shows young fishermen walk into the ocean to board an artisanal fishing boat in Nouakchott, Mauritania, Friday, Dec. 10, 2021. In May 2021 a boat from Mauritania full of dead men was found off the coast of the Caribbean Island of Tobago. Who were these men and why were they on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean? Two visual journalists sought answers, uncovering a story about migrants from West Africa who seek opportunity in Europe via an increasingly popular but treacherous Atlantic route. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

This image provided by World Press Photo is part of a multimedia project by Associated Press' Renata Brito and Felipe Dana titled Adrift, won the World Press Photo Africa Regional Winner Open Format category and shows Moussa Sako, an asylum-seeker from Mali, who survived 22 days aboard a Mauritanian boat drifting in the Atlantic Ocean covers his face during an interview with the Associated Press in Guadalajara, Spain, Sunday, Nov. 14, 2021. In May 2021 a boat from Mauritania full of dead men was found off the coast of the Caribbean Island of Tobago. Who were these men and why were they on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean? Two visual journalists sought answers, uncovering a story about migrants from West Africa who seek opportunity in Europe via an increasingly popular but treacherous Atlantic route. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

This image provided by World Press Photo and taken by Julia Kochetova is part of a series titled War is Personal which won the World Press Photo Open Format Award. Amidst tens of thousands of civilian and military casualties and an effective stalemate that has lasted for months, there are no signs of peace on the horizon for Russia's war in Ukraine. While news media updates its audience with statistics and maps, and international attention drifts elsewhere, the photographer has created a personal website that brings together photojournalism with the personal documentary style of a diary to show the world what it is like to live with war as an everyday reality. (Julia Kochetova/World Press Photo via AP)

This image provided by World Press Photo and taken by Julia Kochetova is part of a series titled War is Personal which won the World Press Photo Open Format Award and shows a stabilization point near Bakhmut, Ukraine, of the 5th assault brigade and 77th brigade. Hospitalliers battalion - volunteer battalion of combat medics are helping here. Amidst tens of thousands of civilian and military casualties and an effective stalemate that has lasted for months, there are no signs of peace on the horizon for Russia's war in Ukraine. While news media updates its audience with statistics and maps, and international attention drifts elsewhere, the photographer has created a personal website that brings together photojournalism with the personal documentary style of a diary to show the world what it is like to live with war as an everyday reality. (Julia Kochetova/Der Spiegel/World Press Photo via AP)

This image provided by World Press Photo and taken by Julia Kochetova is part of a series titled War is Personal which won the World Press Photo Open Format Award and shows the training of mobilized conscripts of 68th brigade in Donetsk region, not far from frontline. 68th brigade recently liberated Blagodatne village during the Ukrainian counter-offensive. The instructors came from US, working for NGO "Saber".Amidst tens of thousands of civilian and military casualties and an effective stalemate that has lasted for months, there are no signs of peace on the horizon for Russia's war in Ukraine. While news media updates its audience with statistics and maps, and international attention drifts elsewhere, the photographer has created a personal website that brings together photojournalism with the personal documentary style of a diary to show the world what it is like to live with war as an everyday reality. (Julia Kochetova/Der Spiegel/World Press Photo via AP)

This image provided by World Press Photo and taken by Alejandro Cegarra for The New Times/Bloomberg is part of a series titled The Two Walls which won the World Press Photo Long-Term Project Award and shows Carlos Mendoza, a Venezuelan migrant, crossing the Rio Grande river to seek asylum in the United States. Piedras Negras, Mexico, 7 October 2023. (Alejandro Cegarra/The New York Times/Bloomberg/World Press Photo via AP)

This image provided by World Press Photo and taken by Alejandro Cegarra for The New Times/Bloomberg is part of a series titled The Two Walls which won the World Press Photo Long-Term Project Award and shows a migrant walking atop a freight train known as "The Beast." Migrants and asylum seekers lacking the financial resources to pay a smuggler often resort to using cargo trains to reach the United States border. This mode of transportation is very dangerous; over the years, hundreds have fallen onto the tracks and have been killed or maimed. Piedras Negras, Mexico, 8 October 2023. (Alejandro Cegarra/The New York Times/Bloomberg/World Press Photo via AP)

This image provided by World Press Photo and taken by Lee-Ann Olwage for GEO is part of a series titled Valim-babena which won the World Press Photo Story of the Year Award and shows Dada Paul Rakotazandriny (91), who is living with dementia, and his granddaughter, Odliatemix Rafaraniriana (5), get ready for church on Sunday morning at his home in Antananarivo, Madagascar. 12 March 2023. (Lee-Ann Olwage/Geo/World Press Photo via AP)

This image provided by World Press Photo and taken by Lee-Ann Olwage for GEO is part of a series titled Valim-babena which won the World Press Photo Story of the Year Award and shows Joeline (Fara) Rafaraniriana (41) watches her father, Dada Paul Rakotazandriny (91) clean fish at home on Sunday afternoon. A typical Sunday consists of the family attending church in the morning and spending time together in the afternoon. Fara works during the week and as the sole provider and carer for her daughter and father struggles to manage all her responsibilities in the absence of assistance by her siblings who live close by. Mandrosoa Ivato, Antananarivo, Madagascar. 12 March 2023. (Lee-Ann Olwage/Geo/World Press Photo via AP)

This image provided by World Press Photo and taken by Mohammed Salem of the Reuters news agency won the World Press Photo Award of the Year and shows Palestinian woman Inas Abu Maamar, 36, embracing the body of her 5-year-old niece Saly, who was killed in an Israeli strike, at Nasser hospital in Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip, October 17, 2023. (Mohammed Salem/Reuters/World Press Photo via AP)