"The Biggest Little Farm" is a documentary with the title, and much of the rosy fantasy, of a picture book. John and Molly Chester didn't, like Matt Damon and Scarlett Johansson, buy a zoo. But they got start-up investors to help them purchase a 213-acre farm just north of Los Angeles.

"Not just any farm," John says of their ambitions for an old-school, biodiverse plot. "We're talking about something out of a children's book."

When they excitedly survey their new land, the couple, newly liberated from day-jobs and a cramped Santa Monica apartment near Los Angeles, bubble with anticipation. "I wonder if we can grow bananas," says Molly.

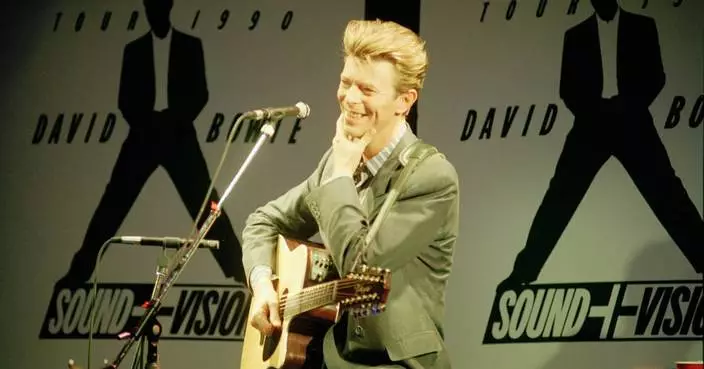

This image released by Neon shows an aerial view of Apricot Lane Farms in a scene from "The Biggest Little Farm." (Neon via AP)

The imagined romance of agrarian life has long been the stuff of daydreams, from "Anna Karenina" to "Shaun the Sheep." ''The Biggest Little Farm," which chronicles the eight years that followed for the Chesters, captures what happens when two city folk try to really do what many urbanites only imagine before determining that we could never, really, bring ourselves to wear overalls.

The steep learning curve for the Chesters is steeper, still, because they aren't merely dipping their toe into farming. Unlike the mono-crop farms all around them, their Apricot Lane Farms will be a restorative farm with its own self-perpetuating ecosystem that, once up-and-running, coasts on nature's own cycles. There will be ducks and chickens and a bull and over 70 varieties of fruit. "Diversify, diversify, diversify," says their consultant Alan York, a surfer dude-type who speaks mystically about riding a farm like you would a wave.

Harmony, of course, proves elusive. Their bliss is constantly interrupted by the toil of daily farm life and a host of invaders: coyotes, snails and birds, not to mention drought and wildfires.

Capturing those pains was always part of the plan. Molly and John, who's also the film's director and narrator, began their quixotic journey documenting every step of the way, leading to previous segments on Oprah's OWN network. Their lives are laid out here for inspiration and envy, much like Joanna and Chip Gaines on HGTV's "Fixer Upper." The Chesters are about soil the way the Gaines are about shiplap.

"The Biggest Little Farm" can at times feel like a larger, better-produced version of the kind of viral video that spreads on Facebook, equal parts uplifting and self-congratulating. It's a self-contained film about a self-contained paradise.

But John, a former cameraman for Animal Planet, documents the place with "Planet Earth" specificity, with views from the microscopic to the aerial. And "The Biggest Little Farm" is most invested in capturing not the Chesters' renewal, but the rehabilitation of their land, from dried-out hillside to lush, recycling idyll.

And as much as it might seem silly to say about a long-term documentary composed significantly of people doing yard work, "The Biggest Little Farm" couldn't be more urgent. The United Nations, in its first comprehensive biodiversity report, on Monday said extinction is looming for more than 1 million species of plants and animals. On a planet overwhelmed by habitat loss, the Chesters managed to build an ark. We're going to need a lot more of them.

"The Biggest Little Farm," a Neon release, is rated PG by the Motion Picture Association of America for mild thematic elements and brief language. Running time: 92 minutes. Two and a half stars out of four.

MPAA Definition of PG: Parental guidance suggested.

Follow AP Film Writer Jake Coyle on Twitter at: http://twitter.com/jakecoyleAP