Joe Biden was on friendly turf when he appeared in January 2018 at a San Francisco health care conference to call for urgency in the search for a cancer cure. He had come before an invitation-only crowd of 2,000 health care industry leaders and investors to tout the work of his Biden Cancer Initiative, the nonprofit that has been his defining venture since leaving the Obama White House more than two years ago.

The former vice president first thanked his physician son-in-law, Dr. Howard Krein, a board member of the Biden nonprofit and a top executive of the health care tech company that hosted the event. Next, Biden called out to "one of my closest friends" in the audience, Joe Kiani, a medical device firm mogul and longtime donor.

Biden then launched into a call to arms. "Imagine," he told his standing-room-only crowd, "what we can do together."

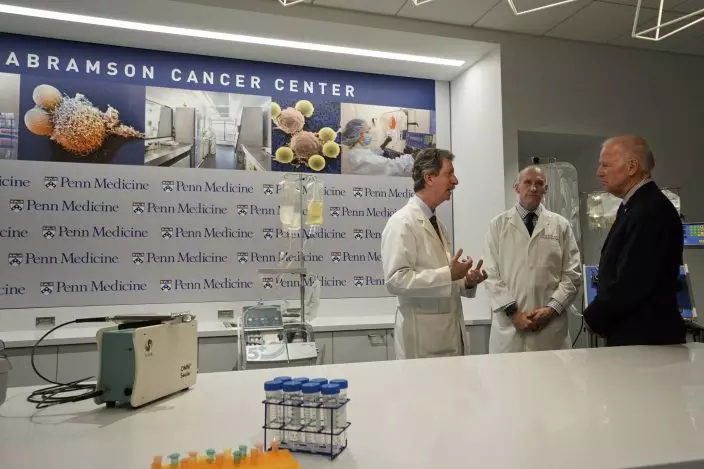

FILE - In this Jan. 15, 2016 file photo, Vice President Joe Biden listens to Dr. Bruce L. Levine PH.D., left, and Dr. Carl H. June M.D., center, in the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Biden’s defining venture since leaving the Obama White House is the Biden Cancer Initiative, a nonprofit aimed at speeding a cancer cure in memory of his son. (AP Photo Joseph Kaczmarek, Pool)

Since leaving office, Biden has made it his mission to mobilize the health care industry to fight cancer as a tribute to his son Beau, who succumbed to the disease in 2015. Biden enlisted family, friends and donors and has promoted his crusade at health care industry events. And drug companies, hospitals, insurers, medical associations and charities have pledged millions to the cause. In its first two years, the Biden Cancer Initiative has listed 58 separate collaborations joined by more than 200 health care companies and other groups.

Now that Biden is running for president those relationships highlight his reliance on a powerful industry with much at stake in the outcome of the 2020 race. Many of the organizations he's celebrated — including some tied to the men Biden mentioned in the 2018 speech— have health care-related financial or regulatory interests before the federal government. A Biden administration would inevitably have to reckon with their efforts to influence its policies, ethics experts say.

"Fighting cancer is clearly a worthy cause," said Arthur Caplan, professor of bioethics at New York University and director of the college's Division of Medical Ethics. But the nonprofit's reliance on health care industry partners poses questions about whether a "Biden administration would give favorable treatment for anyone who supported his foundation in the past."

FILE - In this Oct. 18, 2016 file photo, Vice President Joe Biden speaks at the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate in Boston, about the White House's cancer "moonshot" initiative — a push to throw everything at finding a cure within five years. Biden’s defining venture since leaving the Obama White House is the Biden Cancer Initiative, a nonprofit aimed at speeding a cancer cure in memory of his son. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

At a campaign stop last week in Ottumwa, Iowa, Biden made clear his aim to mount a government-run cancer-fighting effort. "I promise you, if I'm elected president, you're going to see the single most important thing that changes in America is we're going to cure cancer," he said.

Biden's campaign said his nonprofit's operations would not be incorporated into a Biden administration cancer-fighting effort. That could mean the nonprofit might continue working with health care industry organizations with Biden in the White House.

Biden has taken several steps to defuse ethics concerns. He and his wife, Jill, dropped off the nonprofit's board in April, a move aimed at eliminating potential conflicts during his presidential campaign. And Biden's campaign told The Associated Press that if elected, he would issue an executive order and staff guidance enforcing "the highest ethical standards." Biden's campaign did not provide details, but cited President Barack Obama's 2009 order, which tightened ethics standards and limited the hiring of lobbyists.

The nonprofit discloses the names of its partners but much less on their financial pledges. An AP review of all 58 collaborations found precise funding figures available for only 13 partnerships, totaling more than $400 million. The nonprofit expects to provide more dollar figures in future updates.

The Biden campaign insists health care industry cooperation is necessary to marshal the resources needed to make a difference.

Biden commits to "the highest standards of ethical culture," said deputy campaign manager Kate Bedingfield. She added that Biden believes that success in curing cancer "will only be achieved by calling on the resources and creativity of a robust private-public partnership: government, health care nonprofits, innovative medical startups, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies and patient advocacy groups."

To be sure, the influence minefield facing a Biden administration doesn't match the ethics concerns that have vexed the Trump administration. President Donald Trump made it easy for foreign and domestic interests to try to influence U.S. policy when he retained his stake in his private real estate company. Meanwhile, Trump's personal nonprofit, the Donald J. Trump Foundation, was dissolved last year after it was sued by the New York attorney general for operating as a "checkbook to serve Mr. Trump's business and political interests."

The Biden nonprofit's use of cancer-related collaborations echoes the Clinton Global Initiative, a global partnership program run by the Clinton Foundation, the charity set up by former President Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton. The Clinton Foundation came under fire throughout Hillary Clinton's 2016 presidential campaign for its dealings with foreign and corporate donors and the CGI program was ended in 2017. While Biden's group has a far smaller budget and operations, both groups have emphasized funding and collaborations between companies and other groups.

"The larger question," said Douglas White, former director of Columbia University's Master of Science Program in Fundraising Management, "is should candidates be in the business of creating nonprofits if they're still aiming for a political career."

The Bidens launched their cancer nonprofit in June 2017 to carry on the work of the White House Cancer Moonshot Task Force, the anti-cancer effort that Biden headed in his final year as vice president. Greg Simon, who directs the Biden nonprofit and had a similar role with Cancer Moonshot, said the Biden Cancer Initiative is ethically careful in its work with corporate and other interests. The nonprofit takes no direct donations from drug companies and its grants have no restrictions on their use, he said.

The nonprofit has accepted direct donations from some corporate-tied interests. Its largest gifts include $1 million each from foundations headed by Napster and Facebook entrepreneur Sean Parker and by Susan Buffett, daughter of billionaire investor Warren Buffett. Parker and Buffett have donated heavily to political candidates and committees.

But the bulk of the money supporting Biden's nonprofit comes in the form of indirect pledges. That funding does not go directly to the Biden Cancer Initiative, but instead is managed by the participating organizations to fund their research and work. Biden's group then uses its platform to promote the partnerships.

That offers good publicity to such well-known drug companies like Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Meyers Squibb and Johnson & Johnson. They are among a host of corporate partners and other groups that work on cancer-related projects promoted by the Biden nonprofit and also lobby with the federal government.

Before stepping down from the nonprofit's board, Biden was the organization's top booster in public and goal-setter in private. Biden did not sign off on the nonprofit's collaborations, but he was briefed on each one, Simon said. Biden spoke regularly with health care industry players in roundtables, hospital visits and on the phone. And he made public appearances approximately every other month for the last two years. Biden was not paid for the speeches, but accepted travel and lodging — as did other speakers — when the events were run by nonprofit groups, Simon added.

Even with those precautions, Biden's 2018 appearance at the StartUp Health Festival in San Francisco showed how some of those he has celebrated have ties to health care industry groups with interests before the federal government. Krein, who is married to Biden's daughter, Ashley, is on the Biden Cancer Initiative's board of directors while working as chief medical officer at StartUp Health, a venture capital and health tech firm, which lobbied the government last year on health industry technology regulations.

Last September, StartUp joined a coalition of health care tech and medical groups that wrote to the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services urging rule changes to aid "connected health technologies." The coalition asked the agency to provide flexibility in Medicare's compensation of patient monitoring and other tech systems used in hospital care. StartUp has provided investment seed money to some small firms specializing in health technologies.

Biden has twice appeared at StartUp's annual event, a high-profile attraction for the firm. StartUp has invested in more than 280 small firms since its launch in 2011 and was raising money for an investment fund at the time of Biden's speech last year. StartUp's fund ultimately took in $31 million from a group of outside investors, including the Swiss drug firm Novartis, Japan's Otsuka Pharmaceutical and China-based insurer Ping An Ventures.

Simon said: "There's never been a request from the Bidens to do anything to feature or highlight StartUp." Neither Krein nor his brother, Steven, the firm's CEO, responded to requests for comment from the AP in emails and phone calls.

In his 2018 StartUp speech, Biden also hailed Kiani for doing "great, great work." Kiani's corporate prominence in the health care industry, his company's heavy spending on lobbying and his political ties to the former vice president all point to potential clout in a Biden administration.

Kiani's Masimo Corp. is a leading manufacturer of patient monitoring equipment. The firm spent $80,000 a year between 2013 and 2018 on federal lobbying, including efforts to suspend or eliminate a tax on medical device products originally part of the Obama administration's 2013 health care law. The firm has called the tax an "impediment to innovation."

Biden's campaign said he backed the medical device tax during the Obama administration and continues to support it.

Kiani and Masimo have no role with the Biden nonprofit, Simon said. But they have other Biden connections.

In February 2017, two weeks after leaving the White House, Biden spoke at an Orange County, California, event held by the Kiani-led Patient Safety Movement Foundation, which aims to reduce patient deaths in hospitals. Masimo Corp. has invested in StartUp. Another Kiani-led charity, the Masimo Foundation, donated $1 million to the Biden Foundation, a separate Biden family nonprofit that suspended operations in April in advance of the former vice president's entry into the 2020 race.

Kiani is also aiding Biden's presidential bid. He and his wife, Sarah, co-hosted a Biden fundraiser in Los Angeles in May, and they each gave $5,000 in 2017 to American Possibilities, a political committee organized by Biden.

A spokeswoman for Kiani said that he declined comment.