Michael Olenick was 19 and living a secret social life, letting loose with friends at a speakeasy-like bar with blacked-out windows and one of the few floors in town where men danced with other men. Then the lights came on and the police strode into the Stonewall Inn.

Adrenaline pumping, Olenick worried about getting arrested but also about the action outside — shouting, sirens, sounds of objects being thrown. Gay people got harassed on the streets often enough that he wondered whether they were getting attacked.

He never thought that what he was hearing early June 28, 1969, would echo for 50 years. It was the start of a rebellion that helped propel and transform the modern LGBTQ rights movement, leaving a legacy in politics, policing and personal lives.

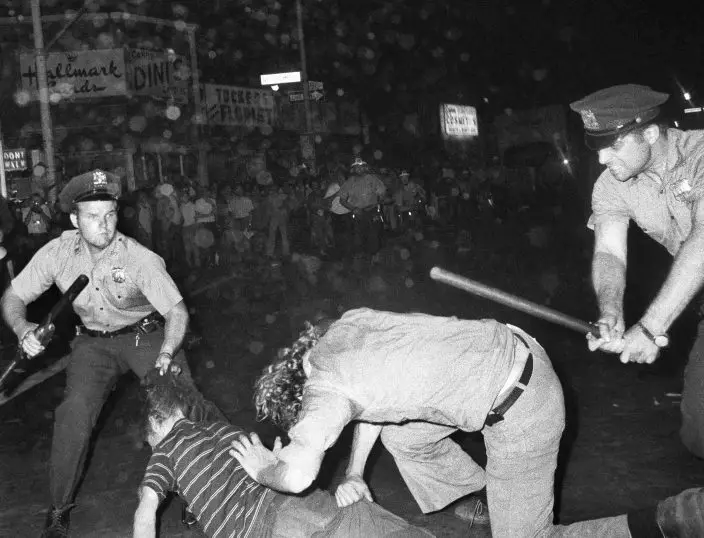

FILE - In this Aug. 31, 1970, file photo, a New York Police Department officer grabs a youth by the hair as another officer clubs a young man during a confrontation in Greenwich Village after a Gay Power march in New York. A year earlier, the June 1969 uprising by young gays, lesbians and transgender people in New York City, clashing with police near a bar called The Stonewall Inn, was a vital catalyst in expanding LGBT activism nationwide and abroad. (AP PhotoFile)

"I'm standing there, not knowing what was going on. That was the horror," recalls Olenick, who was among many patrons police eventually allowed to leave the bar. "And then what came from it was the joy — the enlightenment for the country, for the world, that, 'Hey, we're here. Get over it.'"

Many details of what happened at the Stonewall are enveloped in differing perspectives, disputes and the uncertainty of half-century-old memories.

But the outlines are clear. At a time when homosexuality was defined as mental illness and showing same-sex affection could be deemed illegal, a diverse crowd of hundreds of gay men, bisexuals, lesbians and transgender people refused to go quietly after police raided the bar. They confronted the officers, hurling coins, bottles, invective and more.

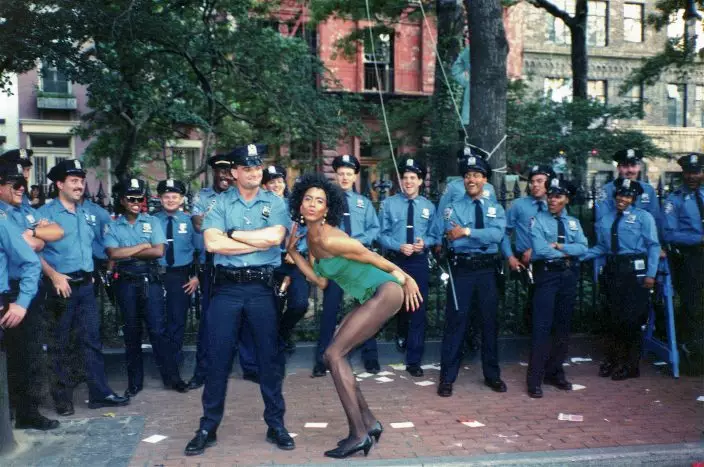

In this June 24, 1990, photo provided by Thomas Garguilo, Darryl Brantley, a waiter at New Jimmy's, poses with New York Police Department officers while dressed in a Playboy bunny outfit as they await the Pride parade to make its way past the bar. New Jimmy's was a bar that was created and opened in 1990 in the space of the original Stonewall Inn, which went out of business shortly after the riots in 1969. (Thomas Garguilo via AP)

Some bucked arrest and scuffled with officers, who took cover inside the bar for a time before riot police arrived. Demonstrations, defiance and arrests continued for several more nights.

The U.S. had seen some organized gay protests and spontaneous fights between LGBTQ people and police. But Stonewall proved to be a turning point. It kindled a sustained burst of organizing that changed the tone and volume of LGBTQ activism, and it altered how some people saw themselves in a society that had relegated many to shadows and shame.

"I knew that I deserved the same rights as anybody else, but it took all of that to make me realize that we, as a people, could fight back," says Mark Segal, who was weeks out of high school when he went to the Stonewall that night and emerged an activist.

In this 1970 photo provided by The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center, demonstrators rally and march during the first Gay Liberation Day march in New York. Gay and lesbian demonstrations grew nationwide following the 1969 New York Police Department raid of gay patrons at The Stonewall Inn in New York's Greenwich Village. (Leonard FinkThe Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center via AP)

"How could anyone have imagined that going out for a night would end up being history?"

'THINGS HAVE CHANGED A LOT SINCE I WAS A COP'

The night's assignment: Search for evidence of unlicensed alcohol sales at the unlicensed Stonewall Inn.

This June 15, 2019, photo provided by Michael Olenick shows Olenick at his home in Hemlock Farms, Penn. Olenick was inside The Stonewall Inn the night it was raided in 1969. As a 19-year-old at the time, he didn't want to get arrested and didn't join in the resistance. But as he reflected over the next few days, he thought "this was the start of something big...and it gave me more of a sense of myself for being a gay kid." (Courtesy of Michael Olenik via AP)

Officer Charles Broughton had been on similar raids before. They were common at New York's gay bars, often unlicensed and run by the underworld. Patrons rarely made waves.

As Broughton recalls, the focus was on people selling illegal drinks, not buying them. Several Stonewall employees were arrested.

While news and other accounts describe police checking people wearing clothes deemed gender-inappropriate — at the time, sometimes considered an illegal "disguise" — and arresting some, Broughton says he wasn't involved in that and didn't judge how bar patrons wanted to live.

In this 1971 photo provided by The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center, demonstrators march through the streets during the Gay Liberation Day march in New York. Gay and lesbian demonstrations grew nationwide following the 1969 New York Police Department raid of gay patrons at The Stonewall Inn in New York's Greenwich Village. (Rudy GrilloThe Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center via AP)

He didn't anticipate being corralled in the Stonewall by an angry crowd, hoping he wouldn't get hurt as something crashed against the window.

He would ultimately be shoved and kicked by three people, according to an arrest report; Broughton says he doesn't remember it. Overall, at least six people were arrested in the melee. At least four officers — not Broughton — were treated for injuries, according to police reports obtained by historian Jonathan Ned Katz and others. The reports don't reflect any protesters' injuries.

Broughton doesn't regret the Stonewall raid. "I did my job at the time," he says.

In this 1971 photo provided by The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center, demonstrators march through the streets during the Gay Liberation Day parade in New York. Gay and lesbian demonstrations grew nationwide following the 1969 New York Police Department raid of gay patrons at The Stonewall Inn in New York's Greenwich Village. (Leonard FinkThe Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center via AP)

But the New York Police Department apologized this month.

"The actions taken by the NYPD were wrong, plain and simple," Commissioner James O'Neill said.

The words of contrition came from a police force that now protects — and participates in — LGBT Pride celebrations that commemorate resistance to its own action.

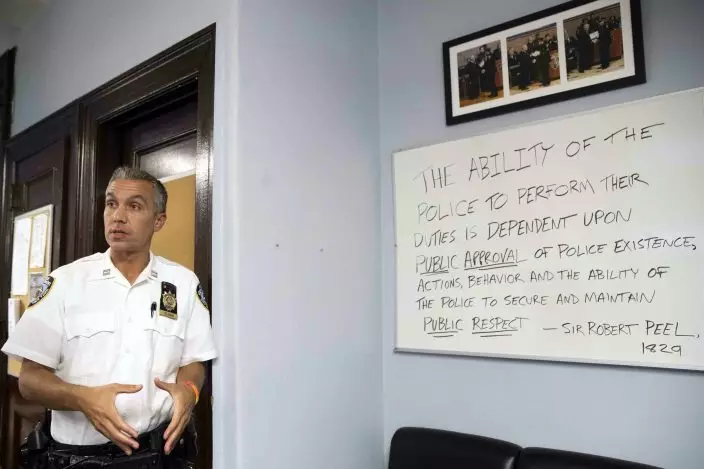

In this Tuesday, June 18, 2019, photo, Capt. Kevin Coleman, commanding officer of the New York City Police Department's 10th Precinct, talks about one of his favorite quotes by Sir Robert Peel during an interview in New York. Coleman has been open throughout his 16-year career about being “a cop who happens to be gay.” (AP PhotoMary Altaffer)

The Gay Officers Action League has hundreds of members from the NYPD and some nearby agencies. LGBT officers have attained such high-profile positions as precinct commander.

Capt. Kevin Coleman, who oversees a Manhattan precinct, has been open throughout his 16-year career about being "a cop who happens to be gay."

Other officers appreciate his frankness, he says.

In this Sunday, June 26, 2016, photo, a police officer applauds as parade-goers shout and wave flags during the New York City Pride Parade, in New York City. June is LGBT Pride Month, commemorating the Stonewall riots, which occurred in June 1969 following a New York Police Department raid of gay patrons at The Stonewall Inn. (AP PhotoMel Evans)

"The NYPD, like all of society, evolves," he said this week as a rainbow pride flag flew among others outside the stationhouse. "If we look at Stonewall, 50 years ago, through today, that's an example of how far we've come."

Still, LGBT activists say heavy-handed policing isn't a thing of the past, particularly for transgender people and minorities. Some activists weren't assuaged by O'Neill's apology for the raid, and it elicited mixed feelings in police circles.

"I don't blame the cops because they worked in a different time period. They answered to different types of policies," said Sgt. Ed Mullins, a union leader. Like O'Neill, he joined the force in the 1980s.

In this 1972 photo provided by The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center, demonstrators march through the streets during the Gay Liberation Day march in New York. Gay and lesbian demonstrations grew nationwide following the 1969 New York Police Department raid of gay patrons at The Stonewall Inn in New York's Greenwich Village. (Rudy GrilloThe Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center via AP)

Broughton, for his part, wasn't offended by the NYPD's apology.

"Things have changed a lot since I was a cop. ... If it helps, it's good," said Broughton, now a long-retired detective. "Listen, all of us have had family members that are part of that community. And none of us are better than anybody else."

'WE WANTED SOCIETY TO CHANGE'

Mark Segal, founder of the Philadelphia Gay News, stands in the rain during an interview outside The Stonewall Inn, Tuesday, June 18, 2019, in New York. In the aftermath of the 1969 uprising of gays following a New York Police Department raid at the Stonewall, Segal emerged as a gay rights activist just weeks out of high school. "I knew that I deserved the same rights as anybody else," said Segal. (AP PhotoBebeto Matthews)

Scrawled on the Stonewall's boarded-up windows the night after the raid were words that blew Dale Mitchell's mind: "Support Gay Power."

"I had never seen 'gay' as part of a political slogan before," he recalls, "let alone associated with the word 'power.'"

Mitchell, then 20, didn't feel so powerful. He'd had to drop out of college after breaking with his family over his sexual orientation, and he was living in a drug-ridden rooming house with an older man who was mortified by the prior night's Stonewall rebellion.

Mark Segal, founder of the Philadelphia Gay News, prepares for an interview during his visit to The Stonewall Inn, Tuesday, June 18, 2019, in New York. In the aftermath of the 1969 uprising of gays following a New York Police Department raid at the Stonewall, Segal emerged as a gay rights activist just weeks out of high school. "I knew that I deserved the same rights as anybody else," said Segal. (AP PhotoBebeto Matthews)

Mitchell, though, was struck by it and by the crowd that gathered the night after the raid, calling for gay power as another tense standoff developed with police.

Two years later, he would become Indiana University's first openly gay student senator and tell a student newspaper gay people were "showing that our power is real." This month, he was honored as the Boston Pride parade's grand marshal for his advocacy for LGBT senior citizens through the group SAGE and other efforts.

Heading toward the Stonewall that night after the raid, Charles Evans viewed it from the vantage point of a black man from the segregated South, where he'd seen "you had to fight for everything that you got."

In this June 7, 2019, photo, Boston Pride Parade grand marshal Dale Mitchell speaks at a Pride event in Boston. Mitchell was at The Stonewall Inn when riots broke out between gays and police 50 years earlier in New York's Greenwich Village. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

"Now, I got to fight for my rights to be who I am," the college student thought as he joined in the second night of protests, heartened at how many supporters had gathered.

Circulating in the crowd, Karla Jay heard the urgency but feared it would fade. Yet a month later, she was among hundreds on a march to the Stonewall, mobilized by the nascent Gay Liberation Front.

Formed in the rebellion's wake, GLF was more radical than earlier groups that staged pioneering, decorous demonstrations and emphasized a message that gay people were mainstream.

In this June 7, 2019, photo, Boston Pride Parade grand marshal Dale Mitchell, middle, reminisces with Charles Evans, left, and Paul Glass at a Pride event in Boston. All three men were at The Stonewall Inn when riots broke out between gays and police 50 years earlier in New York's Greenwich Village. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

GLF members "didn't care any more about those niceties," said Jay, then a graduate student who became the group's first female leader. "We wanted society to change."

Short-lived but influential, GLF marched in Times Square and picketed news publications. Members started a spectrum of other groups, including a transgender-advocacy organization founded by Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera .

Activists pressed officials to pass anti-discrimination laws and psychiatrists to stop classifying homosexuality as a mental disorder. The new groups held dances to socialize in the open.

In this June 8, 2019, photo, Boston Pride Parade grand marshal Dale Mitchell waves as he rides in a convertible past the Statehouse during the Gay Pride Parade in Boston. Mitchell was at The Stonewall Inn when riots broke out between gays and police 50 years earlier in New York's Greenwich Village. (AP PhotoElise Amendola)

"We had to be out, loud and in your face," concluded Segal, the teen spurred to activism by the Stonewall uprising. A GLF member, he founded a gay youth group, disrupted TV news and talk shows to raise the movement's visibility, and now publishes the Philadelphia Gay News.

For Paul Glass, Stonewall's impact was more private but no less important. He came out to his family a few weeks later.

"It was liberating," says Glass, Evans' husband.

Wes Enos speaks to reporters before the start of a Stonewall 50 event at the New-York Historical Society in New York, Sunday, June 2, 2019. Enos works to share LGBT life stories through the Generations Project, an organization he founded after recognizing many of his peers knew little about their elders. (AP PhotoSeth Wenig)

A WINDING ROAD OF CHANGE

Today, the Stonewall Inn is part of the first national monument to LGBT history . It has undergone various physical and ownership changes over the years, but it's still a bar, and a rallying point for LGBTQ activists along a winding road of political and social change .

With gay marriage legal nationwide, polls show majorities of Americans now support same-sex marriage and nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ people; 20 states have such laws. A federal proposal passed the House this spring but faces long odds in the Senate.

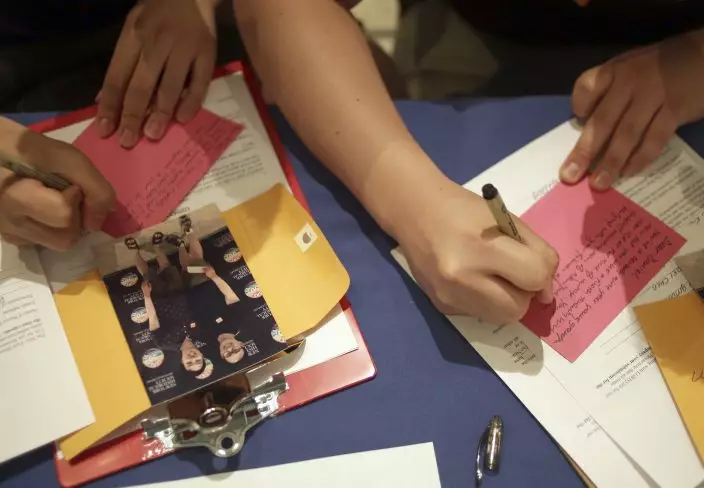

Daniel Kim, right, and Michael Chen write notes to accompany their photograph to go into a time capsule at the New-York Historical Society in New York, Sunday, June 2, 2019. The letters share LGBT life stories through the Generations Project, a project committed to preserve LGBTQ history. (AP PhotoSeth Wenig)

Enduring differences over the movement are as visible as a rainbow pride flag that went up over the Wisconsin state Capitol this month. Where some saw a banner of inclusivity, others viewed it as waving a provocative cause in the public's face .

"It is divisive," complained state Rep. Scott Allen, a Republican.

'WE HAD COME SO FAR, AND SO MUCH HAD BEEN FORGOTTEN'

Karla Jay, a gay rights activist, author, gay and lesbian studies pioneer, strolls along Stonewall Park, which is decorated with Pride flags, during an interview, Monday, June 3, 2019, in New York. In the wake of the 1969 uprising of gays following a New York Police Department raid at The Stonewall Inn bar, for which the park is named, Jay was among hundreds mobilized by the nascent Gay Liberation Front, who marched to the site showing that gay people were mainstream. (AP PhotoBebeto Matthews)

One afternoon this month, people started tucking notes and keepsakes into envelopes at the New-York Historical Society, there to stay for the next half-century in the Stonewall 50 Time Capsule.

There were flyers for 1980s nightclubs where one man found a social community, and newspaper clippings about being a lesbian police officer and parent in the 1990s. A young transgender woman left a note to her future self: "I love you for being true to you."

Wes Enos put in a letter about helping to create a time capsule dedicated to the legacy of an event decades before his birth. At 32, he has regretted how little many of his peers know about the lives of older LGBTQ people.

In this Friday, June 7, 2019, photo, Karla Jay, right, speaks during the book launch of "In Search of Stonewall," at the New York Historical Society. In the wake of the 1969 uprising of gays following a New York Police Department raid at The Stonewall Inn bar, for which the park is named, Jay was among hundreds mobilized by the nascent Gay Liberation Front, who marched to the site showing that gay people were mainstream. (AP PhotoMary Altaffer)

"It felt like we had come so far, and so much had been forgotten," says Enos, who founded an intergenerational storytelling organization called the Generations Project. It's collaborating on the time capsule, to be sealed next year.

Justin Sams wrote out: "You're beautiful. You're worthy. You're brave. You're courageous."

The 27-year-old actor hopes to read his message again in 2069. But he also hopes it will "let the fellow LGBTQ brothers and sisters know that they're worthy and they can keep fighting," he said.

Karla Jay, a gay rights activist, author, gay and lesbian studies pioneer, poses during an interview, Monday, June 3, 2019, in New York. In the wake of the 1969 uprising of gays following a New York Police Department raid at The Stonewall Inn bar, Jay was among hundreds mobilized by the nascent Gay Liberation Front, who marched to the site showing that gay people were mainstream. (AP PhotoBebeto Matthews)

"And hopefully, they won't have to fight."

Justin Sams, left, takes a picture with George Stewart during a Stonewall 50 time-capsule event at the New-York Historical Society in New York, Sunday, June 2, 2019. Sams shared his message in the Generations Project, a project committed to preserving LGBTQ history and will next be read again in 2069. (AP PhotoSeth Wenig)