A Venezuelan teenager who lost his eyesight when he was hit by police buckshot during a protest said Friday that he wants to continue studying.

Wearing reflective sunglasses, 16-year-old Rufo Chacón also spoke about difficult living conditions in his home state of Táchira, where he was injured during a demonstration over a lack of cooking gas early this month. Asked what he likes to eat, he smiled and said chocolate and ice cream are his favorites.

And he described a new life without sight.

16-year-old Rufo Chacon, wearing reflective sunglasses, speaks to a group of reporters outside the offices of Foro Penal, a Venezuelan human rights organization, in Caracas, Venezuela, Friday, July 19, 2019. The Venezuelan teenager who lost his eyesight when he was hit by police buckshot during a protest says he wants to continue studying. (AP PhotoAriana Cubillos)

"You see continuous darkness," Chacón told journalists outside the Caracas office of Foro Penal, a human rights group. "It's like having your eyes shut and seeing nothing, absolutely nothing."

Chacón's story stands out, even in a country with seemingly countless cases of deprivation and suffering. Images of the boy grimacing and clutching his bloodied face right after he was sprayed with police pellets circulated widely on social media, causing revulsion among many Venezuelans accustomed to years of economic hardship and political conflict.

The shooting highlighted concerns about security forces using harsh tactics to quell discontent as Juan Guaidó, the U.S.-backed opposition leader, tries to oust President Nicolás Maduro, who counts Cuba and Russia among his supporters.

16-year-old Rufo Chacon, wearing reflective sunglasses, and his mother Adriana Parada are met by a gaggle of reporters as they arrive to the offices of Foro Penal, a Venezuelan human rights organization, in Caracas, Venezuela, Friday, July 19, 2019. A Venezuelan teenager who lost his eyesight when he was hit by police buckshot during a protest says he wants to continue studying. (AP PhotoAriana Cubillos)

On Friday, the United States announced sanctions on four officials of Venezuela's military intelligence unit, saying the action was linked to the death of Capt. Rafael Acosta Arévalo, a Venezuelan navy officer allegedly tortured in state custody. The restrictions, which follow similar measures against Maduro and more than 100 other Venezuelan officials, freeze any U.S. assets that the men have and bar them from doing business with Americans.

Venezuela's human rights record fell under more scrutiny after a scathing report about abuses issued by Michelle Bachelet, the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights who visited the country in June. Venezuelan authorities said the report was biased and ignored a record of violence by the opposition, whose attempt to stage a military rebellion on April 30 failed.

This week, authorities in Venezuela released a young musician who was jailed six weeks ago after venting her frustration with Maduro's government on social media. Karen Palacios had been held at a military prison and accused of inciting hate under a law passed by a pro-Maduro congress in 2017.

Two police officers have been arrested for "cruel" conduct in Chacón's case, according to the attorney general's office in Venezuela. However, Alfredo Romero, the head of Foro Penal, said the suspects had not been transferred away from their unit and to a prison in line with a judicial order.

On Friday, Chacón appeared composed. There were dabs of cream on his face, to heal wounds from the police projectiles. After the shooting, medics plucked pellets from his eye sockets.

His mother, Adriana Parada, said her son has good and bad days. She blamed Venezuela's problems on its government and said she gets angry sometimes when she thinks about her son's plight.

She said Chacón needs a medical procedure for prosthetic eyes.

Yet she also talked about what seems impossible.

"As a mother, I have to make my son see again," she said.

PUTUCUAL, Venezuela (AP) — Some of the 10 women and teenage girls who recently came to a medical clinic in eastern Venezuela for free contraceptives fidgeted a bit when a community health worker taught them how to use an IUD, condoms and birth control pills correctly.

The health worker also asked what they knew about HPV, the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world and the cause of nearly all cervical cancer. The women, ages 16 to 33 — two of whom had traveled to Putucual by boat and bus — only one had learned about human papillomavirus in middle school. The rest had talked about it with friends or cousins, but never their parents.

None knew HPV vaccines exist, even though Venezuelan pediatricians have long recommended giving all children the vaccine starting at age 9.

Venezuela’s government has repeatedly broken its promise to provide the shots for free, and many public-school teachers don't follow the requirement to teach sex ed. President Nicolás Maduro 's administration claims the well-being of youth and women is a priority, but the onus is on parents to talk to their kids about HPV and pay for the vaccines at private clinics. That's out of reach for most in a country where private-sector workers earn $202 a month on average, and public employees' monthly minimum wage is $3.60 plus $100 in bonuses.

Most HPV infections are asymptomatic and go away without treatment. But some can lead to genital warts and cancers, primarily of the cervix, but also of the anus, penis and throat.

Official health care statistics are elusive in Venezuela, making it virtually impossible to know the rate of HPV infection or how many people have been vaccinated either privately or by nongovernmental organizations. HPV vaccine coverage estimates from the World Health Organization show a blank space for Venezuela.

In 2022, Maduro’s administration estimated 30% of Venezuelan women are affected by cancer-causing strains of HPV. But the Ministry of Popular Power for Health did not publicly provide the data nor historical figures to show how the rate may have changed.

Health care professionals in the South American country told The Associated Press that the government’s figure is an undercount.

“With HPV, all governments have a social and moral debt to the female population,” said Dr. Carlos Cabrera, an OB-GYN in private practice and director of the maternal fetal medicine program at the Central University of Venezuela. “But people don’t like to talk about sexual and reproductive health.”

When HPV shots first hit the market in the mid-2000s, the oil-dependent state's coffers were flush. The price of oil — Venezuela’s most valuable resource — was steadily climbing and the country produced more than a million barrels a day. In 2009, doctors urged the government of President Hugo Chávez to introduce the HPV vaccine into the country, but they were ignored.

In 2015, Ministry of Health officials appeared ready to start offering HPV shots, mentioning in the agency’s annual performance report that the country’s vaccine schedule would include them and they "would be administered starting in 2016.” By this time, Venezuela's budget holes due to financial mismanagement were apparent, but U.S. economic sanctions had not yet crippled the oil industry.

Venezuela's last vaccine promise came in late 2022 after it reached an agreement with GAVI, a public-private global alliance that helps poor countries procure vaccinations. Government officials said shipments were expected for 2023, but no shots were distributed then, and they are also not listed among those being offered during national vaccination week.

The Ministry of Popular Power for Communication and Information did not respond to questions from the AP about the status of the vaccines, including reasons for the delay.

GAVI, whose assistance is time-limited and requires government funding commitments, said in a statement that Venezuela “reconfirmed its ... intent” to introduce the HPV vaccine in November 2023. It did not answer the AP's question about when it expected the first shots to arrive, saying only that rolling out vaccines takes preparation time.

The health ministry’s vaccination schedule still does not list the HPV vaccine. But that has not stopped state television from occasionally airing a two-minute cartoon of a Maduro-lookalike superhero — “Super Mustache” — whose adversaries are accused of wanting to “destroy everything” in Venezuela, including the “vaccines for the youngest women.” Globally, girls and young women are the primary demographic for the HPV shot.

Private practices in Venezuela that obtain the vaccine through importers sell it for $100 or more, depending on the brand and city, and recommend one or two boosters — which cost extra. Very few can afford that in a country where paychecks of public and private-sector employees aren't enough to cover a month of food for a family of four, which exceeds $350.

Awareness about HPV is another issue: Public schools used to teach about STIs, giving students a chance to ask questions that they might not have felt comfortable bringing to their parents.

But educators now largely ignore the requirement to teach the subject — either due to personal beliefs or because meager pay forces teachers to find second or third jobs, to the point that they're not in the classroom five days a week.

“In theory, on paper, we have a decent sex education program that adheres to international standards, with correct messages,” said Dr. Lila Vega, a pediatrician and member of the Network of Mothers, Fathers and Representatives of Venezuela, an NGO that promotes the participation of parents and guardians in schools. “But in reality, we are not even teaching addition and subtraction, and sex education is not a priority.”

Under Chávez, the ministries of education and culture edited and printed several free textbooks. “Life and Comprehensive Health” for seventh graders had lengthy explanations on teen pregnancy, birth control methods and the cancer risks posed by HPV infections. It included an image of “possible lesions caused by HPV.”

Maduro’s administration last printed the textbooks in 2015. Education officials later set up a digital library to which teachers can refer students, but the health book was never uploaded. Some teachers still share a PDF version of the book with their students, and others refer kids to old copies in school libraries.

Adriana Yeguez, 33, who participated in the session at the clinic in Putucual run by the global medical charity Doctors Without Borders, believes adolescents like her 16-year-old son need more information than what they can get on their own or at school. So, she and her partner are talking to him about HPV.

“We do talk to him, especially about infections,” Yeguez said. “What if he gets one? Imagine that! What if there’s no cure or treatment? What if we don’t have money?”

In some Latin American countries, studies showed a lack of parental knowledge about HPV was an obstacle to vaccination. And in Venezuela, physicians say parents and governments also resist the vaccine due to cultural taboos and the false notion that girls will see it as a ticket to promiscuity.

The vaccine prevents more than 90% of cancers caused by HPV. Yuly Remolina, a researcher and oncologist in Mexico City, believes that statistic is the best argument for why governments should provide the shots and parents and young adults should seek them out.

“It is incredible to continue seeing young patients with cervical cancer who cannot be operated on, who have to be given chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and who end up dying of it," said Remolina, who sees patients from Venezuela, Colombia and other Latin American countries.

It's why Daniel Rojas, a community health worker at the Putucual clinic, urged the women and teens to seek medical attention if they suspect an HPV infection: “Don’t let the days go by just thinking ‘Maybe yes, maybe no.’”

A patient leaves with a box of complimentary condoms after visiting the Doctors Without Borders medical clinic in Putucual, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024. While there she attended a discussion led by a community health worker who taught women and teenage girls how to use an IUD, condoms and birth control pills correctly and about HPV infections. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A patient looks at a birth control injection at a Doctors without Borders medical clinic in Putucual, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024. A group of women and teenage girls visited the medical clinic in eastern Venezuela where a community health worker taught them how to use an IUD, condoms and birth control pills correctly and about HPV infections. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

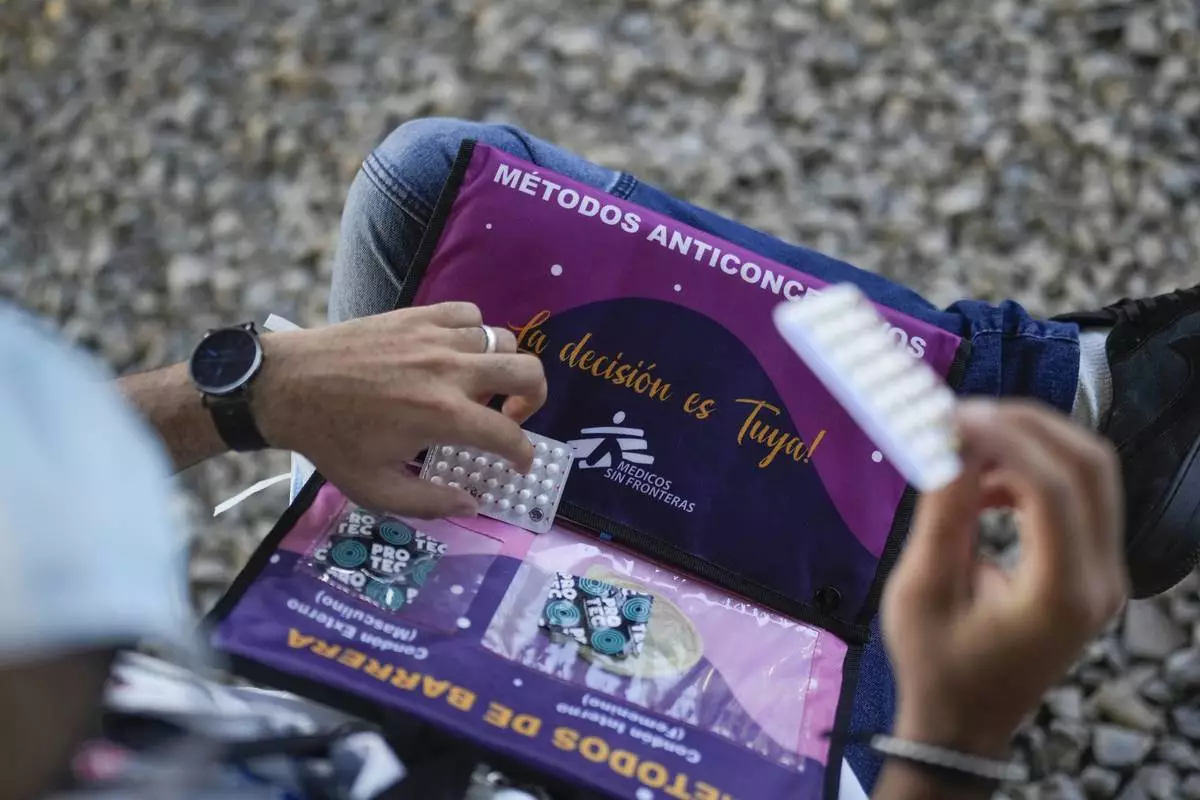

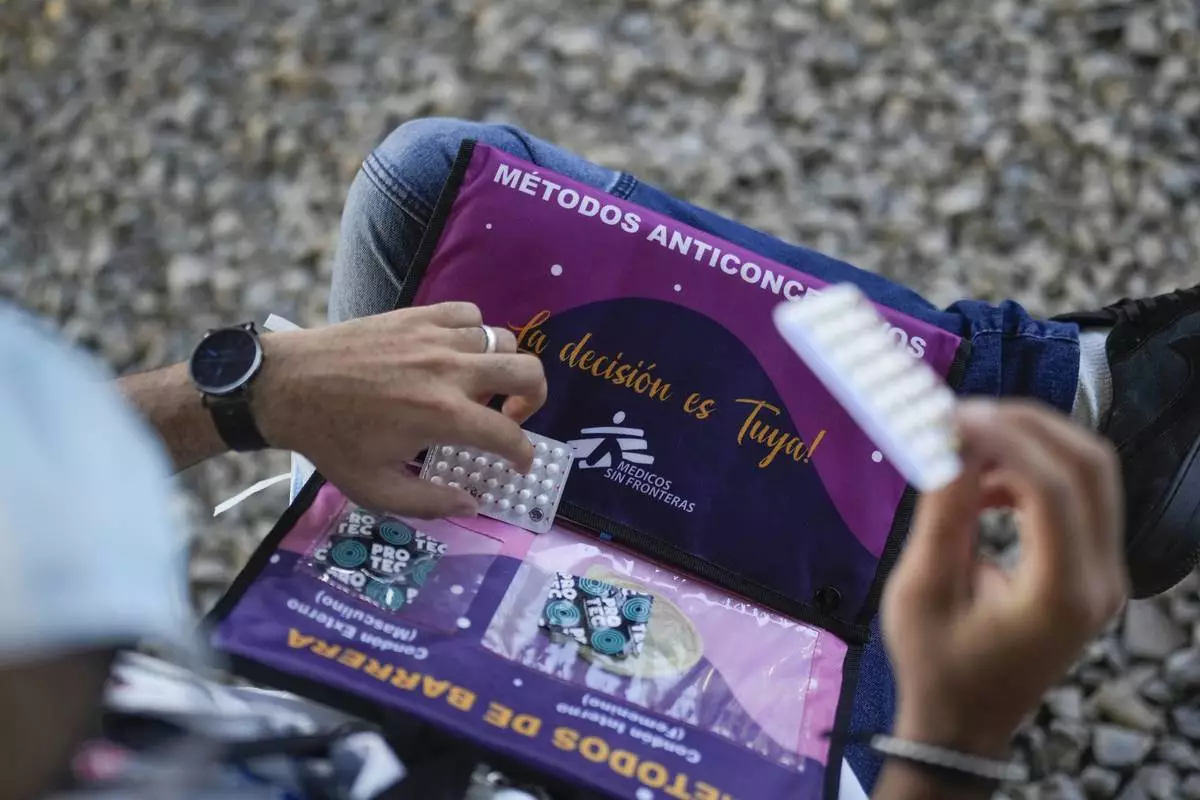

A community health worker teaches a group of women and teenage girls about contraception methods, at a Doctors Without Borders medical clinic, in Putucual, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024. The health worker also asked them what they knew about HPV. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A community health worker teaches a group of women and teenage girls about contraception methods, at a Doctors Without Borders medical clinic, in Putucual, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024. The health worker also asked what they knew about HPV. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A patient receives a birth control implant at a Doctors without Borders medical clinic in Putucual, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024. A group of women and teenage girls visited the medical clinic in eastern Venezuela where a community health worker taught them how to use an IUD, condoms and birth control pills correctly and about HPV infections. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Patients wait their turn to enter a Doctors without Borders medical clinic in Putucual, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024. The women and teenage girls came to the medical clinic in eastern Venezuela for free contraceptives where a community health worker taught them how to use an IUD, condoms and birth control pills correctly and about HPV infections. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Patients' shadows are cast on a wall at a Doctors Without Borders medical clinic in Putucual, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024. A group of women and teenage girls visited the medical clinic in eastern Venezuela for free contraceptives where a community health worker taught them how to use an IUD, condoms and birth control pills correctly and about HPV infections. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix).