With sunlight sparkling off surrounding Yaquina Bay, workers are putting up an ocean-studies building, smack in the middle of an area expected to one day be hit by a tsunami.

Experts say it's only a matter of time before a shift in a major fault line off the Oregon coast causes a massive earthquake that generates a tsunami as much as seven stories tall.

Even as work on Oregon State University's Marine Studies Building was underway in Newport, the Legislature went a step further and repealed a ban on construction of new "critical facilities" in tsunami inundation zones, allowing fire stations, police stations and schools to be built in the potential path of a tsunami.

In this July 22, 2019, photo, Scott Ashford, dean of Oregon State University's college of engineering, describes to the media the university's Marine Studies Building, which is being built in a tsunami inundation zone in Newport, Ore. The plan to build it was controversial from the moment it was announced, but now the state's elected officials have gone a step further by repealing a quarter-century-old ban on construction of critical facilities in tsunami inundation zones along the Oregon coast. (AP PhotoAndrew Selsky)

Passage of the bill in June was little noticed during one of the most tumultuous legislative sessions in Oregon history. But it has since been roundly criticized — including by Gov. Kate Brown, who told journalists the bill's passage was one of her disappointments, even though she signed the measure and previously said it benefited economic development.

Chris Goldfinger, an Oregon State University professor and an earthquake geologist, says putting the $60 million oceanography building in the path of a tsunami is "beyond ironic," and allowing even more construction threatens lives in favor of development.

"It's foolhardy. In every other country in the world, best practice for tsunamis is avoidance, not building in a tsunami zone," Goldfinger said at a symposium for journalists in Newport that included a tour of the construction project.

In this July 22, 2019, photo, Crystal Sanderson with Portland-based Yost Grube Hall Architecture, shows reporters an emergency access ramp that is being built alongside Oregon State University's Marine Studies Building, which is under construction in Newport, Ore. The roof will serve as a vertical evacuation zone for almost 1,000 fleeing a tsunami that an offshore quake would generate, and the ramp will be open around the clock. (AP PhotoAndrew Selsky)

Proponents of the university facility point out that the building will withstand strong earthquakes and be higher than the biggest tsunami. It will also feature a rooftop evacuation site that can accommodate more than 900 people, accessed via an exterior ramp.

Two days of supplies, including water, food and first aid, will be kept on the roof, said Cinamon Moffett, research facility coordinator for the marine center. Once the water subsides, survivors would be evacuated to a community college on a nearby hill, she said.

An earthquake in the Cascadia subduction zone, which extends in the ocean off Northern California to Canada's Vancouver Island, has a 37 percent probability of happening off Oregon in the next 50 years, with a slightly lower chance of one striking near Washington state, Goldfinger said. Cascadia earthquakes have an average magnitude of around 9, making them among the world's biggest.

In this July 22, 2019, photo, the Yaquina Bay Bridge is seen through the window of Oregon State University's Marine Studies Building, which is being erected in a tsunami inundation zone in Newport, Ore. Experts say there is a 37 percent chance that a large Cascadia earthquake will occur off Oregon's shore in the next 50 years, generating a tsunami that will hit many coastal towns. (AP PhotoAndrew Selsky)

Evidence of a Cascadia earthquake's awesome destructive power is visible 30 miles (50 kilometers) up the coast from Newport.

There, a "ghost forest" of Sitka spruces juts up from a beach in the tiny town of Neskowin. An earthquake 2,000 years ago likely caused the ground beneath the trees to plunge, and tsunami debris buried them. The remnants were partially uncovered by storms in 1997. Today, the barnacle-encrusted trees stand like sentinels, facing the Pacific Ocean with vacation homes and a motel nearby.

The last time the ocean reared up from a Cascadia earthquake was in 1700. The estimated magnitude 9 quake sent a tsunami across the Pacific into the coast of Japan, where it flooded farm fields, damaged fishermen's shacks and ascended a castle moat. In the Pacific Northwest and Canada, the impact was far worse, and is described in the folklore of indigenous peoples. One tale describes a struggle between a thunderbird and a whale that caused the earth to shake and the ocean to wash away people and homes.

In this July 22, 2019, photo, gaps are being built into Oregon State University's Marine Studies Building to make it earthquake resistant in Newport, Ore. Construction workers in this Oregon coastal town are erecting a school building, right in the path of a future tsunami that experts say will be generated by a huge offshore earthquake that is certain to occur sooner or later. (AP PhotoAndrew Selsky)

Oregon became a leader in tsunami preparedness when the Legislature, in 1995, banned construction of certain public facilities in inundation zones.

Vancouver Island in Canada's British Columbia province was slammed by the 1700 tsunami. But no law prohibits construction of public buildings in tsunami zones there, according to Emergency Management BC. Washington state requires municipalities and counties to establish rules to limit development in areas that are frequently flooded or could be hit by tsunamis, landslides or other calamities.

California has no state-mandated development restrictions in tsunami zones, said Rick Wilson, senior engineering geologist with the California Geological Survey. But the state recently adopted new language in its building code requiring that certain types of buildings be constructed to withstand tsunami forces, Wilson said. Other states are moving to do the same, using standards from the American Society of Civil Engineers.

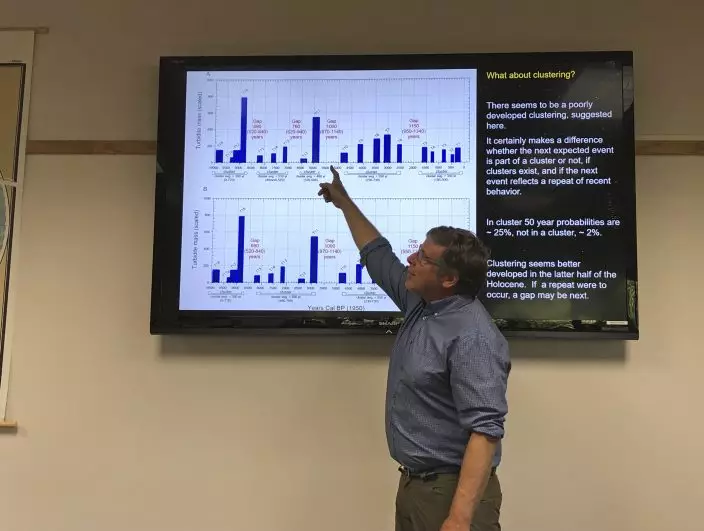

In this July 22, 2019, photo, Chris Goldfinger, an Oregon State University professor and expert on earthquakes and tsunamis, talks to the media about the probability of a large tsunami-generating earthquake occurring off the Oregon coast in Newport, Ore. Goldfinger is sharply critical of a recent repeal of a ban on construction of critical facilities in tsunami inundation zones in Newport, Ore. (AP PhotoAndrew Selsky)

Japan, reacting to a 2011 earthquake and tsunami that left more than 18,000 dead or presumed dead, passed a law allowing towns to set tsunami warning zones and make evacuation and reconstruction plans. The government is spending 1 trillion yen ($9 billion) to build giant seawalls around the northern coastline. Moving to higher ground is not required, though some coastal communities have done so.

"Oregon has gone from sort of a leader in this to full reverse," said Goldfinger, who was attending a seismology conference in Japan when the 2011 earthquake hit.

Oregon lawmakers overwhelmingly repealed the 1995 construction ban in June, as tensions in the Capitol ratcheted up over Republican opposition to a bill addressing global warming. Few people attended hearings at which lawmakers from coastal districts testified in favor of the repeal.

In this July 22, 2019, photo, Oregon State University's Marine Studies Building, which is under construction in a tsunami inundation zone, is seen from the Yaquina Bay Bridge in Newport, Ore. The building, slightly right of center in the middle of the photograph, is surrounded by Yaquina Bay. Construction workers in this Oregon coastal town are erecting the building right in the path of a future tsunami that experts say will be generated by a huge offshore earthquake that is certain to occur sooner or later. (AP PhotoAndrew Selsky)

Democratic Rep. David Gomberg, one of its sponsors, told members of a House committee to imagine the impacts if the state banned new schools, parking garages and police and fire stations in their communities.

"What would be the consequence of that, to your ability to get insurance on your home, your ability to attract a new business into a neighborhood that's not safe enough for fire departments, your ability to resell your home in a neighborhood not safe enough for police departments?" Gomberg asked.

He said the state geology department should "help us rather than to stop ... our communities growing, thriving or continuing."

Gomberg said his bill gives the department responsibility for advising where a new inundation line should be and how risks can be mitigated. He also said he will introduce legislation for Oregon to adopt the American Society of Civil Engineers' tsunami and earthquake building standards.

Republican Sen. Brian Boquist, who was at the center of a Republican walkout over the global warming bill, was the only senator to vote against the repeal. Boquist said in an email that it allows public entities to build, knowing full well the buildings will not survive a tsunami.

It is too soon to tell if coastal cities will use the new leeway to build facilities in inundation zones. Some have been doing the opposite. The town of Seaside, 70 miles (110 kilometers) northwest of Portland, is moving schools out of the tsunami zone.

Newport Mayor Dean Sawyer said his city has no plans to build critical facilities in the inundation zone. But he praised the Marine Studies Building for its rooftop evacuation site, which can fit the population of an entire neighborhood of his fishing town.

"We consider it to be a unique solution," he said.

Meanwhile, the Corvallis Gazette-Times noted in an editorial that while it is possible to design a building that can survive an earthquake and tsunami, "that doesn't answer the question of why we should take the risk in the first place."

The newspaper urged lawmakers to reassess the new law when they convene next year.

Associated Press writers Mari Yamaguchi in Tokyo and Rob Gillies in Toronto contributed to this report.

Follow Andrew Selsky on Twitter at https://twitter.com/andrewselsky