From a tiny Pacific island to a leafy Indiana forest, a handful of sites where the United States manufactured and tested some of the most lethal weapons known to humankind are now peaceful havens for wildlife.

An astonishing array of animals and habitats flourished on six obsolete weapons complexes — mostly for nuclear or chemical arms — because the sites banned the public and other intrusions for decades.

The government converted them into refuges under U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service management, and they now protect black bears and black-footed ferrets, coral reefs and brushy steppes, rare birds and imperiled salmon.

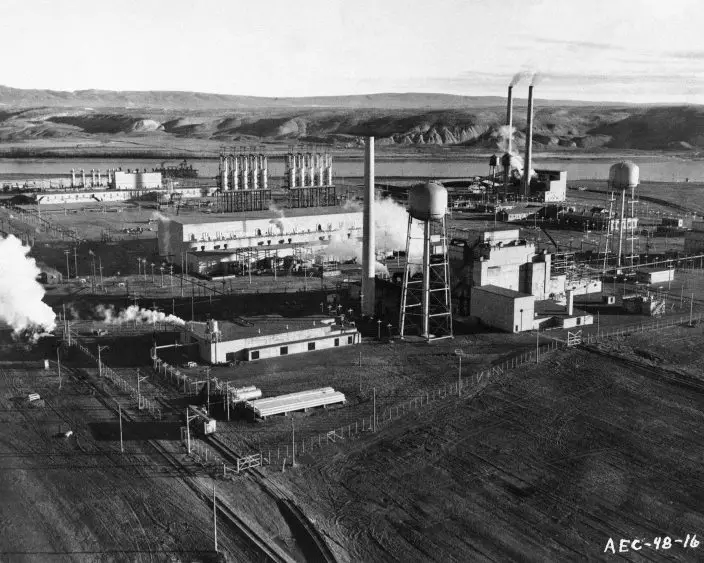

FILE - This Aug. 6, 1945 photo from the Atomic Energy Commission shows one of the production areas at the Hanford Engineer Works, near Pasco in Richland, Wash., where plutonium for the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, was developed. At Hanford, the cleanup as of 2019 has already cost at least $48 billion and hundreds of billions more are projected. (AEC via AP)

But the cost of the conversions is staggering, and some critics say the sites have not been scrubbed well enough of pollutants to make them safe for humans.

The military, the U.S. Department of Energy and private companies have spent more than $57 billion to clean up the six heavily polluted sites, according to figures gathered by The Associated Press from military and civil agencies.

And the biggest bills have yet to be paid. The Energy Department estimates it will cost between $323 billion and $677 billion more to finish the costliest cleanup, at the Hanford Site in Washington state where the government produced plutonium for bombs and missiles.

In this Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2019 photo, a sign designates a boundary of the Hanford Reach National Monument as the world's first large scale nuclear reactor, the B Reactor, is seen in the background where it sits unused on the Hanford Nuclear Reservation along the Columbia River near Richland, Wash. The Energy Department estimates it will cost between $323 billion and $677 billion more to finish the costliest cleanup, at the Hanford Site in Washington state where the government produced plutonium for bombs and missiles. (AP PhotoElaine Thompson)

CONTAMINATION LEFT BEHIND

Despite the complicated and expensive cleanups, significant contamination has been left behind, some experts say. This legacy, they say, requires restrictions on where visitors can go and obligates the government to monitor the sites for perhaps centuries.

"They would be worse if they were surrounded by a fence and left off-limits for decades and decades," said David Havlick, a professor at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs who studies military-to-wildlife conversions. "That said, it would be better if they were cleaned up more thoroughly."

In this Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2019 photo, an osprey feeds a chick nested atop a platform adjacent to the the Hanford Reach National Monument along the Columbia River near Richland, Wash. A handful of sites where the United States manufactured and tested some of the most lethal weapons known to humankind are now peaceful havens for wildlife, where animals and habitats flourished on obsolete nuclear or chemical weapons complexes because the sites banned the public and most other intrusions for decades. But Hanford, where the cleanup has already cost at least $48 billion and hundreds of billions more are projected, may be the most troubled refuge of all. (AP PhotoElaine Thompson)

Researchers have not examined the health risks to wildlife at the cleaned-up refuges as extensively as the potential danger to humans, but few problems have been reported.

At least 30 of the 560-plus refuges managed by the wildlife service have some history with the military or weapons production, the AP found. Most handled conventional weapons, not nuclear or chemical.

Many of the conversions came after the first and second world wars. It was an inexpensive way to expand the national refuge system, especially in urban areas with scarce open space, said Mark Madison, the Fish and Wildlife Service's historian.

In this Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2019 photo, the Columbia River flows under the Vernita Bridge and past the Hanford Reach National Monument, left, and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, right beyond the bridge, near Richland, Wash. Washington state officials are worried that the Trump administration wants to reclassify millions of gallons of wastewater at Hanford from high-level radioactive to low-level, which could reduce cleanup standards and cut costs. (AP PhotoElaine Thompson)

When the Cold War ended in the 1980s, more surplus military lands were earmarked for refuges. Some were among the most dangerously polluted sites in the nation but held swaths of hard-to-find habitat.

REBORN AS IDYLLIC PRAIRIE

Most skeptics agree the refuges are worthwhile but warn that the natural beauty might obscure the environmental damage wreaked nearby.

In this Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2019 photo, a sign at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation warns of possible hazards in the soil there along the Columbia River near Richland, Wash. Washington state officials are worried that the Trump administration wants to reclassify millions of gallons of wastewater at Hanford from high-level radioactive to low-level, which could reduce cleanup standards and cut costs. (AP PhotoElaine Thompson)

The military closed the sites to keep people safe from the dangerous work that went on there, not to save the environment, said Havlick of the University of Colorado.

"It's not because the Department of Defense has some ecological ethic," said Havlick, author of a book about conversions, "Bombs Away: Militarization, Conservation, and Ecological Restoration."

Converting a heavily polluted weapons complex into a wildlife refuge is cheaper than making it safe for homes, schools and businesses, said Adam Rome, who teaches environmental history at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

In this Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2019 photo, a boat motors along Columbia River near the Hanford Reach National Monument near Richland, Wash. A handful of sites where the United States manufactured and tested some of the most lethal weapons known to humankind are now peaceful havens for wildlife, where animals and habitats flourished on obsolete nuclear or chemical weapons complexes because the sites banned the public and most other intrusions for decades. But Hanford, where the cleanup has already cost at least $48 billion and hundreds of billions more are projected, may be the most troubled refuge of all. (AP PhotoElaine Thompson)

"In some cases, they could have conceivably made the site into something that was economically valuable," but that would have cost more, Rome said.

Critics say Rocky Mountain Arsenal in Colorado illustrates the shortcomings of a cleanup designed to be good enough for a refuge but not for human habitation.

Roughly 10 miles (16 kilometers) from downtown Denver, the arsenal was once an environmental nightmare where chemical weapons and commercial pesticides were made. Thousands of ducks died after coming in contact with its wastewater ponds in the 1950s.

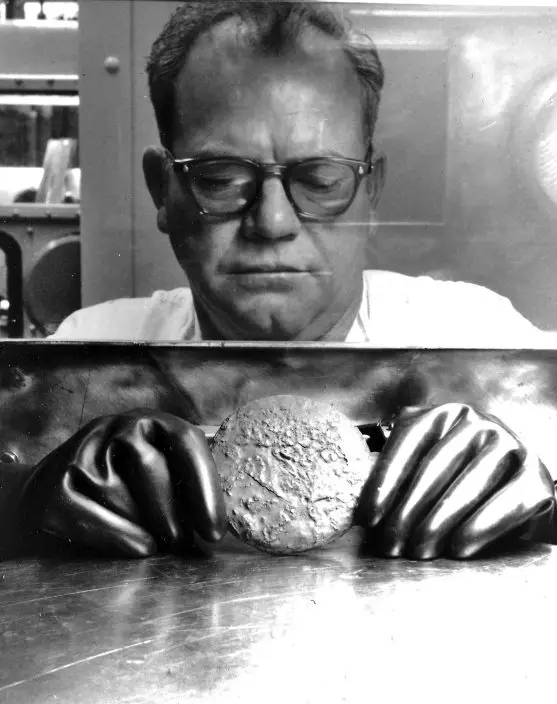

In this Sept. 19, 1973 photo provided by the U.S. Department of Energy, a worker holds a plutonium "button" inside a chamber using protective gloves at the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons plant northwest of Denver. The U.S. Energy Department manufactured plutonium triggers for nuclear warheads at Rocky Flats. It had a long history of leaks, fires and environmental violations. (U.S. Department of Energy via AP)

After a $2.1 billion cleanup, the site was reborn as Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge, with 24 square miles (61 square kilometers) of idyllic prairie where visitors can take scenic drives or hikes.

But parts of the refuge remain off-limits, including specially designed landfills where the Army disposed of contaminated soil. Eating fish and game from the refuge is forbidden. Treatment plants remove contaminants from groundwater to keep them out of domestic wells.

"So there's a huge downside to converting it into a wildlife refuge, because it allows residual contamination to remain in place," said Jeff Edson, a former Colorado state health official who worked on the cleanup.

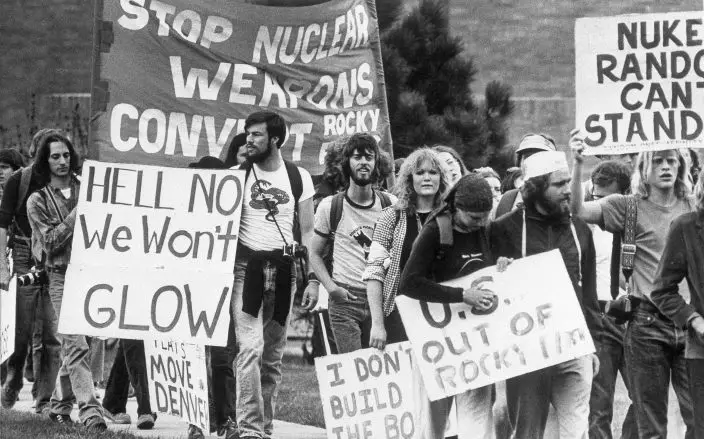

FILE - In this April 28, 1979 file photo, a group of anti-nuclear protesters sets out on a 10-mile hike from Boulder, Colo., to the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons plant, where they joined with more than 7,000 demonstrators at a mass rally seeking closure of the plant. The U.S. Energy Department manufactured plutonium triggers for nuclear warheads at Rocky Flats. It had a long history of leaks, fires and environmental violations. (AP PhotoJE)

"Theoretically, if the Earth still exists in the year 3000, they'll still be monitoring groundwater at the arsenal," he said.

UNEXPLODED ARTILLERY SHELLS

The Army is still struggling with cleaning up Jefferson Proving Ground in southeastern Indiana, part of which became Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge .

In this Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2019 photo, a sign hangs from a fence at the head of a trail at the Rocky Flats Wildlife Refuge in Arvada, Colo. The U.S. Energy Department manufactured plutonium triggers for nuclear warheads at Rocky Flats. It had a long history of leaks, fires and environmental violations. Its rare tallgrass prairie is home to hundreds of species, including an endangered jumping mouse. Part of the site is open to the public. (AP PhotoDavid Zalubowski)

Soldiers test-fired millions of artillery rounds at the proving ground, some made of depleted uranium.

Depleted uranium, a byproduct of nuclear fuel production, is used for armor-piercing shells. Its radiation isn't strong enough to be dangerous outside the body, but its dust is a serious health risk if inhaled or swallowed, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says.

Depleted uranium fragments are scattered on the firing range among 1.5 million rounds of unexploded shells, which makes cleanup dangerous and expensive.

FILE - In this Sept. 26, 2012 file photo, a cormorant dries its wings after diving for fish in Lake Ladora at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in Commerce City, Colo. Roughly 10 miles (16 kilometers) from downtown Denver, the arsenal was once an environmental nightmare where chemical weapons and commercial pesticides were made. Thousands of ducks died after coming in contact with its wastewater ponds in the 1950s. (AP PhotoDonna Bryson)

The Army told the Nuclear Regulatory Commission it could cost $3.2 billion to clean the area for unrestricted use. Its latest plan calls for waiting 20 years in hopes that better, less expensive technology emerges or the unexploded shells degrade to a safe level.

That rankles Tim Maloney, a senior policy director for the Hoosier Environmental Council.

"I think there's a case to be made that just leaving it in place really maintains an unacceptable risk of contamination spreading from the site," he said. "The Army needs to find a way to clean up the depleted uranium safely."

FILE - In this Sunday, Nov. 18, 2018 file photo, hikers head down a trail in the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge in Broomfield, Colo. The former nuclear weapons plant northwest of Denver opened to hikers and cyclists in September 2018, but some activists question whether it’s safe. (AP PhotoDavid Zalubowski)

Some parts of the refuge have been deemed safe — but visitors must watch a safety video and sign a waiver promising not to sue if they're injured by an exploding shell.

A $7 BILLION CLEANUP

Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge , a former nuclear weapons plant northwest of Denver, opened to hikers and cyclists last September, but some activists question whether it's safe.

FILE - In this Sunday, April 14, 2019 file photo, clouds loom over a lake at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge Sunday, April 14, 2019, in Commerce City, Colo. Critics say Rocky Mountain Arsenal in Colorado illustrates the shortcomings of a cleanup designed to be good enough for a refuge but not for human habitation. (AP PhotoDavid Zalubowski)

A $7 billion cleanup concentrated on 2 square miles (5 square kilometers) where workers assembled plutonium triggers for nuclear warheads, and that area is fenced and closed to the public.

The refuge was created on the buffer zone surrounding the production area. State and federal officials say it's safe, but skeptical activists filed a lawsuit saying the federal government didn't test the refuge carefully enough.

Another group asked the courts to release documents from a 27-year-old criminal investigation into the weapons plant, hoping they will show whether the government tracked down and cleaned up all the contamination.

Both those cases are pending in federal court.

SAVING 'SOMETHING POSITIVE'

Hanford — where the cleanup has already cost at least $48 billion and hundreds of billions more are projected — may be the most troubled refuge of all.

Parts of a C-shaped buffer zone around the perimeter are open to visitors as Hanford Reach National Monument . But cleanup costs for an area where contaminated waste is stored are soaring, and Department of Energy investigators say the project has been plagued by fraud and mismanagement.

Washington state officials are worried that the Trump administration wants to reclassify millions of gallons of wastewater at Hanford from high-level radioactive to low-level, which could reduce cleanup standards and cut costs.

The Energy Department told the state it has no current plans to change the classification. State officials say they want long-term and legally binding assurances.

Madison, the Fish and Wildlife Service historian, said the refuges are salvaging something valuable from ecological devastation.

"A lot of the environmental stories are kind of doomy and gloomy, and these are successful ones, something positive," he said.

If agency officials believed the sites were unsafe for the public, he said, they would not work there.

"They're there all the time," Madison said. "They're not going to want to be in a place with chemical pollution or radiation problems."

Follow Dan Elliott at http://twitter.com/DanElliottAP .