The Trump administration is opposing Washington state's effort to make a privately run, for-profit immigration jail pay detainees minimum wage for the work they do.

Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson sued The GEO Group in 2017, saying its Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma must pay the state minimum wage to detainees who perform kitchen, laundry, janitorial, maintenance and barbershop tasks. The lawsuit seeks to force GEO to turn over profits it gained by underpaying them — an amount that could reach into the millions.

U.S. District Judge Robert Bryan has already issued some key rulings in the state's favor. But in a "statement of interest" filed this week, the Justice Department called the lawsuit "an aggressive and legally unjustified effort by the State of Washington to interfere with federal immigration enforcement," and it urged Bryan to reject it.

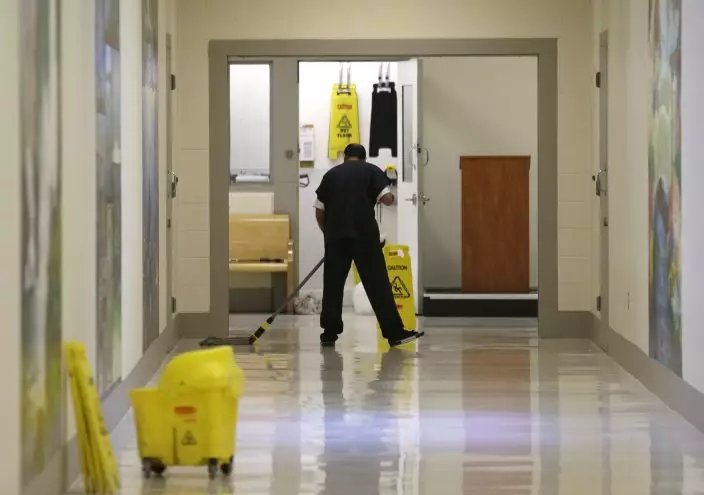

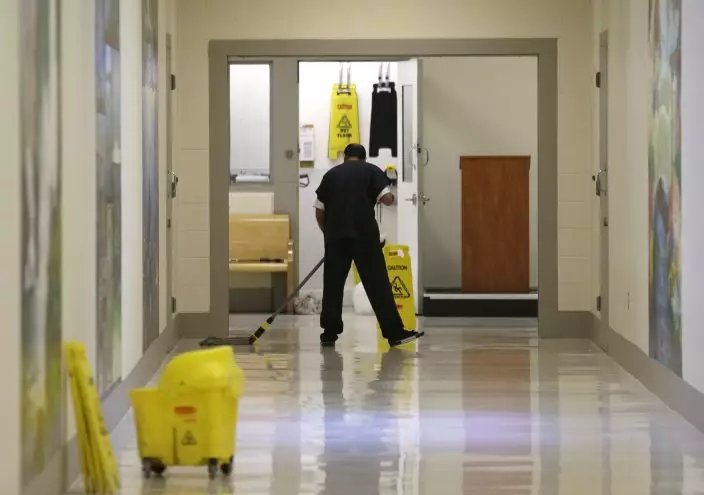

FILE - In this June 21, 2017, file photo, a detainee mops a floor in a hallway of the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Wash., during a media tour of the facility. The Trump administration is opposing Washington state’s effort to make a privately run, for-profit immigration jail pay detainees minimum wage for the work they do. Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson sued The GEO Group in 2017, saying its Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma must pay the state minimum wage to detainees who perform kitchen, janitorial and other tasks. (AP PhotoTed S. Warren, File)

The department said that because the state's minimum wage act doesn't apply to inmates of state prisons, it impermissibly discriminates against the federal government to apply it to a federal contractor holding detainees on civil immigration violations. The judge has already rejected that argument, but on Thursday agreed to reconsider it and other arguments and set a hearing for Sept. 12.

"The State insists that these federal immigration detainees are 'employees' under state law, even though it simultaneously exempts similarly-situated detainees in state facilities from the minimum wage," the Justice Department said. "Basic constitutional principles prevent a State from interfering with the federal government's activities in the way Washington is trying to do here."

The Northwest Detention Center is a 1,575-bed jail, one of the nation's largest privately run immigrant detention centers. On any given day, about 470 of them perform some sort of work through a voluntary program at the facility, earning $1 per day. GEO has the authority to pay more, but Congress will only reimburse it up to that amount.

FILE - In this June 21, 2017, file photo a detainee works in the kitchen of the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Wash., during a media tour of the facility. The Trump administration is opposing Washington state’s effort to make a privately run, for-profit immigration jail pay detainees minimum wage for the work they do. Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson sued The GEO Group in 2017, saying its Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma must pay the state minimum wage to detainees who perform kitchen, janitorial and other tasks.(AP PhotoTed S. Warren, File)

Washington argues it is entitled to enforce the minimum wage law against GEO just as it's entitled to enforce it against any other company. The law does exempt state prisons from paying inmates for work, but it doesn't do the same for private detention centers, it says.

Further, the state says, GEO's contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement requires the detainee work program to comply with all applicable labor laws — including Washington's minimum wage law, since GEO is in a clear employer-employee relationship with the detainees.

"The Trump Administration apparently thinks the for-profit, private company that runs Northwest Detention Center should be above the law," Ferguson said in an emailed statement. "Despite President Trump's position, GEO must comply with Washington law and either pay the detainees that run its facility minimum wage, or pay minimum wage to Washington workers to do the job."

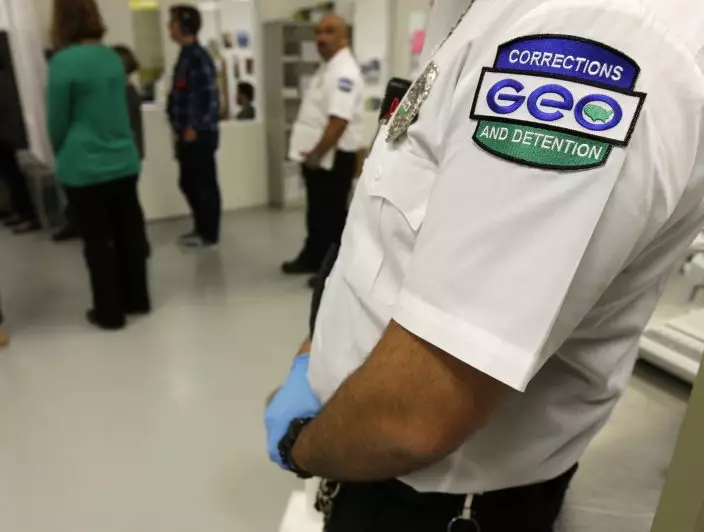

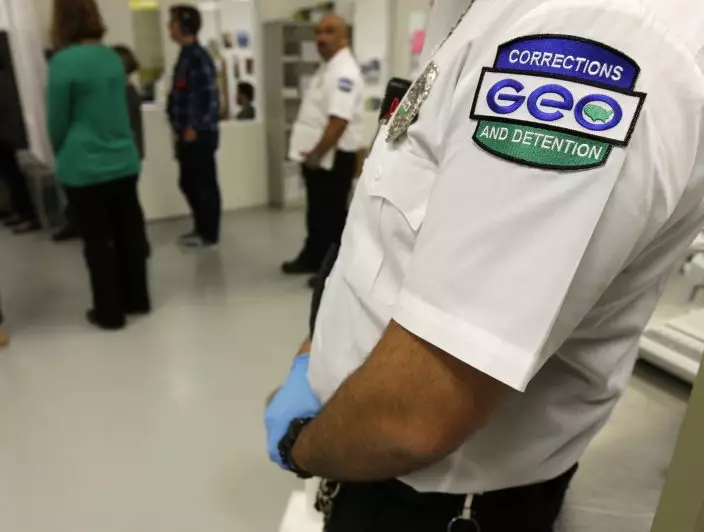

FILE - In this June 21, 2017, file photo, a guard with the GEO Group stands in a detainee processing section of the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Wash., during a media tour of the facility. The Trump administration is opposing Washington state’s effort to make a privately run, for-profit immigration jail pay detainees minimum wage for the work they do.Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson sued The GEO Group in 2017, saying its Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma must pay the state minimum wage to detainees who perform kitchen, janitorial and other tasks. (AP PhotoTed S. Warren, File)

GEO has attacked Ferguson's lawsuit as being "politically motivated." In court documents, the company says the state has known about the dollar-a-day payments since as early as 2009, but that Ferguson did not file a lawsuit until after the 2016 election of President Donald Trump and his implementation of controversial immigration policies.

KYIV, Ukraine (AP) — A big, new package of U.S. military aid will help Ukraine avoid defeat in its war with Russia. Winning will still be a long slog.

The arms and ammunition in the $61 billion military aid package should enable Ukraine to slow the Russian army's bloody advances and block its strikes on troops and civilians. And it will buy Ukraine time — for long-term planning about how to take back the fifth of the country now under Russian control.

“Ultimately it offers Ukraine the prospect of staying in the war this year,” said Michael Clarke, visiting professor in war studies at King’s College London. “Sometimes in warfare you’ve just got to stay in it. You’ve just got to avoid being rolled over.”

The U.S. House of Representatives approved the package on Saturday after months of delays by some Republicans wary of U.S. involvement overseas. It was passed by the Senate on Tuesday, and President Joe Bidensigned it into law on Wednesday.

The difference could be felt within days on the front line in eastern and southern Ukraine, where Russia’s much larger army has been slowly taking territory against massively outgunned Ukrainian forces.

The aid approval means Ukraine may be able to release artillery ammunition from dwindling stocks that it has been rationing. More equipment will come soon from American stocks in Poland and Germany, and later from the U.S.

The first shipments are expected to arrive by the beginning of next week, said Davyd Arakhamia, a lawmaker with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s Servant of the People party.

But opposition lawmaker Vadym Ivchenko, a member of the Ukrainian parliament’s National Security, Defense and Intelligence Committee, said logistical challenges and bureaucracy could delay shipments to Ukraine by two to three months, and it would be even longer before they reach the front line.

While details of the shipments are classified, Ukraine’s most urgent needs are artillery shells to stop Russian troops from advancing, and anti-aircraft missiles to protect people and infrastructure from missiles, drones and bombs.

What’s coming first is not always what front-line commanders need most, said Arakhamia, the Ukrainian lawmaker. He said that even a military giant like the U.S. does not have stockpiles of everything.

“The logic behind this first package was, you (the U.S.) finds our top priorities and then you see what you have in the warehouses,” Arakhamia said. “And sometimes they do not match.”

Hope for future breakthroughs for Ukraine still hangs on more timely deliveries of Western aid, lawmakers acknowledge.

Many experts believe that both Ukraine and Russia are exhausted by two years of war and won’t be able to mount a major offensive — one capable of making big strategic gains — until next year.

Still, Russia is pushing forward at several points along the 1,000-kilometer (600-mile) front, using tanks, wave after wave of infantry troops and satellite-guided gliding bombs to pummel Ukrainian forces. Russia is also hitting power plants and pounding Ukraine’s second-largest city, Kharkiv, which is only about 30 kilometers (some 20 miles) from the Russian border.

Ivchenko said the goal for Ukraine’s forces now is to “hold the line” until the bulk of new supplies arrive by mid-summer. Then, they can focus on trying to recapture territory recently lost in the Donetsk region.

“And probably ... at the end of summer we’ll see some movement, offensive movement of the Ukrainian armed forces,” he said.

Some military experts doubt Ukraine has the resources to mount even small offensives very soon.

The U.S. funding “can probably only help stabilize the Ukrainian position for this year and begin preparations for operations in 2025,” said Matthew Savill, director of military sciences at the Royal United Services Institute, a think tank.

In the best-case scenario for Ukraine, the American aid will give commanders time to reorganize and train its army — applying lessons learned from its failed summer 2023 offensive. It may also galvanize Ukraine’s allies in Europe to increase aid.

“So this just wasn’t about Ukraine and the United States, this really affected our entire 51-country coalition,” said U.S. Congressman Bill Keating, a Democrat who visited Kyiv on Monday as part of a four-member congressional delegation.

Zelenskyy insists Ukraine's war aim is to recapture all its territory from Russia — including Crimea, seized illegally in 2014. Even if the war ultimately ends through negotiation, as many experts believe, Ukraine wants to do that from as strong a position as possible.

Whatever happens on the battlefield, Ukraine still faces variables beyond its control.

Former U.S. President Donald Trump, who seeks to retake the White House in the November election, has said he would end the war within days of taking office. And the 27-nation Europe Union includes leaders like Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico, who have opposed arming Ukraine.

Ukraine’s allies have held back from supplying some arms out of concern about escalation or depleting their own stocks. Ukraine says that to win the war it needs longer-range missiles it could use for potentially game-changing operations such as cutting off occupied Crimea, where's Russia's Black Sea fleet is based.

It wants a longer-range version of Army Tactical Missile Systems, known as ATACMs, from the U.S. and Taurus cruise missiles from Germany. Both governments have resisted calls to send them because they are capable of striking targets deep within Russian territory.

The new bill authorizes the president to send Ukraine the longer-range ATACMS, which have a range of some 300 kilometers (190 miles), “as soon as practicable.” It's unclear what that will mean in practice.

Sometimes, promised weapons have arrived late, or not at all. Zelenskyy recently pointed out that Ukraine is still waiting for the F-16 fighter jets it was promised a year ago.

Meanwhile, Russia is using its advantage in troops and weapons to push back Ukrainian forces, perhaps seeking to make maximum gains before Ukraine's new supplies arrive.

For weeks it has pummeled the small eastern city of Chasiv Yar, suffering heavy losses. Britain's Ministry of Defense says 900 Russian troops are being killed or injured a day in the war.

Capturing the strategically important hill town would allow them to move toward Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, key cities Ukraine controls in the eastern region of Donetsk. It would be a significant win for Russian President Vladimir Putin, who Western officials say is bent on toppling Ukraine’s pro-Western government.

Russian pressure was aimed not just at gaining territory, but on undermining Zelenskyy and bolstering critics who say his war plan is failing, said Clarke of King's College London.

The U.S. aid package decreases the likelihood of a political crisis in Ukraine, and U.S. Speaker Mike Johnson deserves credit for pushing it through Congress, he said.

"He held history in his hands,” Clarke said.

This story has been updated to correct Orbán's title, the Slovak prime minister's name and that the British estimate of daily Russian losses is for the war, not one battle.

Follow AP’s coverage of the war in Ukraine at https://apnews.com/hub/russia-ukraine

From left, U.S. representatives Nathaniel Moran, R-Tx, Tom Kean Jr, R-NJ, Bill Keating, D-Mass, and Madeleine Deane, D-Pa, talk to journalists during a joint news conference outside Saint Michael cathedral in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, April 22, 2024. A newly approved package of $61 billion in U.S. aid may prevent Ukraine from losing its war against Russia. But winning it will be a long slog. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A volunteer makes a camouflage net at a facility producing material for Ukrainian soldiers in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, April 22, 2024. A newly approved package of $61 billion in U.S. aid may prevent Ukraine from losing its war against Russia. But winning it will be a long slog. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Davyd Arakhamia, a lawmaker with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy's Servant of the People party, talks during an interview with Associated Press in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, April 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A woman rallies to raise awareness on the fate of Ukrainian prisoners of war in Kyiv, Ukraine, Sunday, April 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Ribbons with the colors of the European Union and Ukraine are attached to a tree next to memorial wall of Ukrainian soldiers killed during the war in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, April 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

The body of a woman killed by Russian bombardment in Chernihiv, Ukraine, Wednesday, April 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Soldiers carry the coffins of two Ukrainian army sergeants during their funeral in Lviv, Ukraine, Tuesday, April 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)