Seven decades after Israel's founding, the debate over Judaism's place in public life rages on.

Israeli political battle lines often fracture along how the country balances Jewish religion and liberal democracy. These tensions were a central issue in this week's national election, and are sure to influence the composition of the country's next government.

While the country's Jewish majority is largely secular, parties representing the ultra-Orthodox minority have traditionally wielded considerable political power.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addressees his supporters at party headquarters after elections in Tel Aviv, Israel, Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2019. (AP PhotoAriel Schalit)

Acting as coalition kingmakers, religious parties hold a monopoly on many areas of daily life, from the closure of stores and public transport on the Sabbath to Jewish burial and marriage rites.

Israel has granted the ultra-Orthodox community sweeping exemptions from the country's mandatory military draft. This has built resentment among the secular majority, who are required to serve.

After Israel held elections last April, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's prospective governing coalition collapsed because a secular ally, Yisrael Beitenu party leader Avigdor Lieberman, insisted on legislation to force young ultra-Orthodox men to also serve in the military.

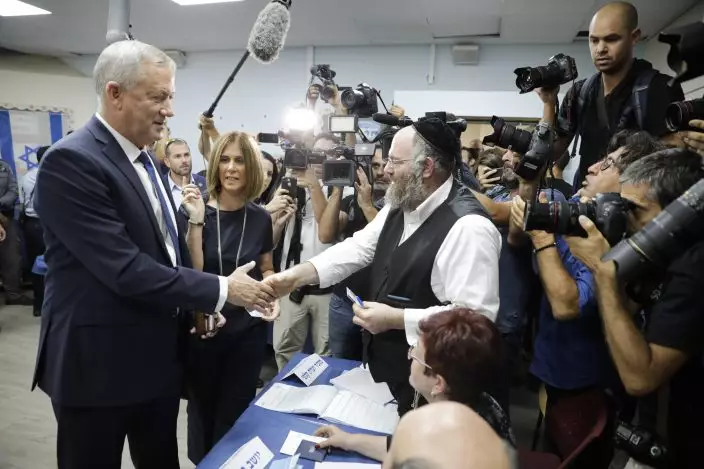

Blue and White party leader Benny Gantz and his wife Revital vote in Rosh Haayin, Israel, Tuesday, Sept. 17, 2019. Israelis began voting Tuesday in an unprecedented repeat election that will decide whether longtime Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stays in power despite a looming indictment on corruption charges. (AP PhotoSebastian Scheiner)

Playing on this theme, Lieberman's party boosted its strength in Tuesday's election and is poised to be a central player in the next coalition government. He is insisting on a broad secular partnership with the country's two largest parties.

"Israelis voted more on religion and state as a result of the political growth and appetite of the ultra-Orthodox parties," said Yohanan Plesner, president of the Israel Democracy Institute, a Jerusalem think tank.

Of Israel's 9 million people, 75% are Jewish. Most of the population is secular or modern Orthodox, and 14% are ultra-Orthodox, according to Israel's Central Bureau of Statistics. Another 20% of the population is made up by the country's Muslim, Christian and Druze Arabs.

As coalition negotiations get set to begin, here's a look at religion's role in Israeli politics:

ORTHODOX

The two ultra-Orthodox parties — the predominantly Ashkenazi United Torah Judaism and Sephardi Shas party representing Jews of Middle Eastern descent — and the religious nationalist Yemina faction, advocate a greater place for Orthodox Judaism in state life, including religious education and shutting public transportation on the Sabbath.

They also have rejected efforts to dissolve a long-standing exemption for religious men to study in seminaries in lieu of having to serve in the military.

Religious Jewish parties won nearly 20% of the vote in Tuesday's repeat election. In recent decades, those parties have typically united with the conservative Likud party to form a governing coalition. But this time, the religious-nationalist bloc fell short of a majority in the Knesset, Israel's parliament, winning only 56 of the 120 seats.

SECULAR

Several of the main liberal parties — Blue and White, Yisrael Beytenu and the Democratic Union — ran on a secular platform, advocating measures such as universal military draft that includes ultra-Orthodox men and civil marriage. Currently, all Jewish marriages in Israel must be performed by the country's Orthodox Rabbinate, which requires that both partners be Jewish and that the ceremony adhere to Orthodox custom.

Lieberman's staunchly secular Yisrael Beytenu party is supported mainly by mostly non-religious, Russian-speaking immigrants from the former Soviet Union.

Blue and White, headed by former army chief of staff Benny Gantz, campaigned ahead of election day with ads calling for a "secular national unity government." Those calls were echoed by Lieberman, who supports a partnership with Gantz and Netanyahu that excludes the ultra-Orthodox parties.

ARABS

The majority of Israel's roughly 20% Arab minority are Sunni Muslims, with the remainder made up of Druze and Christians. Most self-define as traditional or religious, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics. The Joint List of Arab parties, a union of four smaller factions, including a secular nationalist, an Islamist, and a Communist party, won a projected 12 seats in the country's parliament. Most Arabs tend to vote based on national identity rather than along religious lines.