Elizabeth Warren still “has a plan” for everything. She’s just trying to put a more personal face on them.

Being a proud policy nerd helped catapult the Massachusetts senator into front-runner status last summer but may have carried her as far as it can. She has retooled the speech she gives voters at multiple daily campaign stops and has begun stressing that she’s been counted out of fights all her life -- only to find a way to prevail. That's a strategy she's hoping to emulate enough to recover her footing in the Democratic presidential primary race.

“One of the things that I realize is that voters have a right to know not just the policies but also the heart of the person they’re going to pick as president of the United States,” she said after a packed event at a church in Portsmouth on Monday night. “So I put out all the polices. But I also put more of my heart out there for people.”

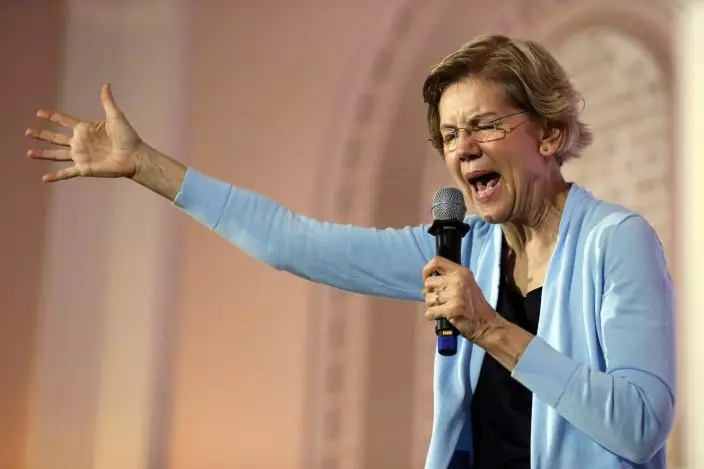

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth, D-Mass., speaks at a town hall campaign event, Monday, Feb. 10, 2020, in Portsmouth, N.H. (AP PhotoRobert F. Bukaty)

Warren has begun telling crowds that, when she was in high school, her mother said she would never go to college — so she used her babysitting money to pay for applications and secured a debate scholarship. She describes beating incumbent Republican Sen. Scott Brown in 2012, despite once being down by nearly 20 points: “I got knocked on my fanny multiple times during that campaign. But you know what I did? I got up each and every time.”

And a new centerpiece of her speech features a February 2017 episode when Warren was on the Senate floor opposing Jeff Sessions’ nomination as attorney general and Republican Majority Leader Mitch McConnell evoked an obscure rule to stop her from speaking. Co-opting McConnell's words, Warren has summed up the experience under the slogan "Nevertheless, she persisted,” which often draws standing ovations.

Those changes likely came too late to help Warren in New Hampshire's primary Tuesday. But her campaign sees the struggles of former Vice President Joe Biden as opening up a wealth of new would-be supporters that she could scoop up in states like Nevada and South Carolina, which vote next on the Democratic presidential calendar.

Her team sees a winnowing field perhaps eventually setting up a fight between Warren and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a billionaire who is pouring vast swaths of his fortune into the states that vote on Super Tuesday, March 3. Warren has called for a wealth tax on the nation’s rich, and her message of economic populism could give her a second campaign wind against someone like Bloomberg -- if she can make it that far.

A wild card could be Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who genera ted late-stage enthusiasm in New Hampshire. Still, Warren’s campaign is betting that staff infrastructure she’s already built in 30 states means she can outlast Klobuchar, giving her a path to the nomination -- albeit one that is narrowing the longer she goes without winning a state.

Top advisers point to Warren’s highlighting the Senate speech from 2017 as a new and important way to excite voters. The senator mentioned it after a largely forgettable performance in Friday night’s New Hampshire debate. It got such a good reaction that she said it on stage before an arena full of cheering Democrats at a state party dinner the next night. Now it’s the loudest applause line at her rallies.

Warren insists the race is still fluid, saying “the best evidence of that” is incorrect past predictions about who would be the strongest primary candidate to this point.

“Who was supposed to be in this race today, and who wasn’t? I think I wasn’t, and a lot of people who were supposed to have locked it up by this point are not here,” she said after a rally in Rochester, New Hampshire.

The senator also argues that she is the best candidate to unify the Democratic Party, a subtle shot at Bernie Sanders, the race's other strong progressive candidate, who is calling for political revolution and has emerged in a near tie at the top of the field in Iowa's caucuses with a more centrist White House hopeful, former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigeig.

As part of the unification process, Warren has hired staffers who worked for Democratic White House candidates who left the race, and she's even begun spelling out how she’s incorporated their plans into her own: abortion rights proposals from California Sen. Kamala Harris, a paid family leave plan promoted by New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand and calls for universal prekindergarten programs that former Obama administration housing chief Julián Castro championed.

“She’s trying to get the message out that that is part of her platform," said Beth Carta-Dolan, a restaurant owner who met Warren when she stopped at a cafe in Conway, in northern New Hampshire's breathtaking White Mountains. "So that the people who supported these other people are now being drawn in to understand that she represents them as well.”

Catch up on the 2020 election campaign with AP experts on our weekly politics podcast, “Ground Game.”