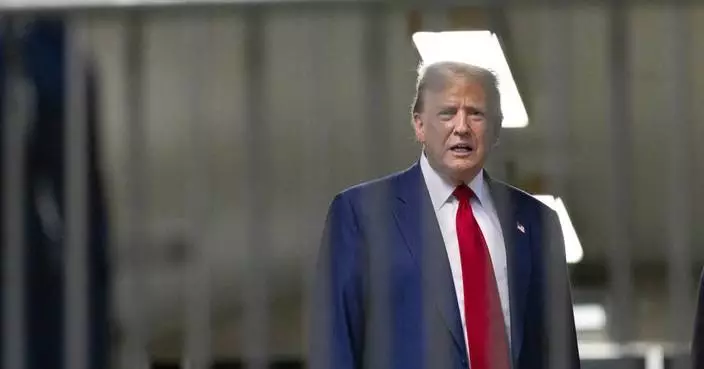

President Donald Trump would like to freeze the moment. He had relished watching a fractious Democratic debate. He had soaked in affirmation at a rally. And he was spending the night at one of his hotels, on the Las Vegas Strip.

Trump, making a rare four-day swing through the West, was exuding reelection confidence Thursday after the prior night's prize fight of a debate in Las Vegas. He reveled in the intra-party squabbling and the weak debut debate performance turned in by former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg, according to aides and allies.

When Trump woke up Thursday morning in his gilded Las Vegas hotel, his base during the four-state western trip, he tuned in to the post-debate coverage and displayed his glee.

Repurposing one of Bloomberg's own quotes about the Democratic infighting, Trump tweeted: “The real winner last night was Donald Trump.” He tacked on his own coda: “I agree!”

The night before, after his own campaign rally in Phoenix, Trump summoned reporters to his office aboard Air Force One to join him in watching a replay of the debate on the return flight to Las Vegas. His motorcade jammed up traffic for more than a half hour as it passed the casino that had hosted the Democrats' debate in the lead-up to the party caucuses in Nevada on Saturday.

Trump was holding his third campaign rally in three days later Thursday in Colorado Springs. But his preoccupation with the scrambled nomination race for the Democrats seeking to replace him has been clear throughout the trip.

Bloomberg has been the most disconcerting force in the 2020 race for Trump since the ultra-billionaire entered the fray in November and spent more than $400 million, which rocketed him in the polls in just three months.

Trump's campaign poll numbers have improved since his impeachment trial wrapped up in January and his campaign has broken fundraising records, raising $60 million in January and $14 million this week in California alone. But Bloomberg's willingness to spend near-unlimited sums to defeat Trump this fall, and the mocking tone of many of his ads, have deeply rankled the president.

Trump's campaign had organized itself around the strategy that it would be able to paint any rival as an extreme liberal, a "socialist" or worse, and concerns mounted that strategists would have to come up with a different plan should Bloomberg win the nomination.

Trump's team saw the debate as validating his reelection strategy and providing a fresh opening for Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, a self-described Democratic socialist, to gain a significant delegate lead on Super Tuesday. The president was hopeful that panic from more moderate Democrats at Sanders' rise would only further fracture the Democratic Party.

“We don't care who the hell it is,” Trump boasted Wednesday. "We're going to win.”

Trump on Thursday placed a round of calls to confidants, echoing the thoughts he had posted on Twitter — at times with more colorful language — and opining that Bloomberg did not appear ready for the moment, according to two Republicans close to the White House who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly about private conversations.

Long insecure about Bloomberg’s wealth, Trump told confidants that the debate proved money alone did not lead to his own electoral success.

His eldest son echoed the thought as he tweeted during the debate.

“Like a deer in the headlights! Like I said last week Mini, you can’t buy personality or wit and the whole world just saw it,” Donald Trump Jr. wrote.

Between three rallies and a pair of high-dollar fundraisers, Trump sought to use his western swing to highlight administration policies that delivered on campaign promises and appealed to key demographics.

On Wednesday, he ceremoniously signed new environmental regulations that eased water restrictions on farmers in the heavily Republican California Central Valley. On Thursday, Trump spoke to a graduating class of ex-prisoners in a renewed appeal to communities of color, as he championed his administration’s work on criminal justice reform.

"Your future does not have to be defined by the mistakes of your past,” Trump told the graduates, before turning to political topics.

Trump received updates on the debate's opening minutes Wednesday evening moments before he took the stage at a rally in a packed Phoenix arena and promptly delivered his first review.

“I hear he's getting pounded tonight — you know he's in a debate,” Trump said about the man he has dubbed “Mini Mike” because of his short stature. “I hear that pounding. He spent $500 million so far and I think he has 15 points. Crazy Bernie was at 30."

The military defector was killed in a hail of gunfire and then run over by a car in Spain. The opposition figure was struck repeatedly with a hammer in Lithuania. The journalist fell ill from a suspected poisoning in Germany.

Since President Vladimir Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine, attacks and harassment of Russians — prominent or not — have been blamed on Moscow's intelligence operatives across Europe and elsewhere.

Despite attempts by Western governments to dismantle Russian spy networks, experts say the Kremlin apparently is still able to pursue those it perceives as traitors abroad in an attempt to silence dissent. Opponents of Putin increasingly fear the long arm of Moscow’s security services, including in countries they once thought were safe.

“We just escaped Russia and had this illusion that we’ve escaped prison,” said journalist Irina Dolinina, who works for the independent outlet Important Stories, based in the Czech capital of Prague.

Dolinina and colleague Alesya Marokhovskaya were harassed in 2023, leading to fears they were under surveillance. They were sent threatening messages via comments on the media outlet's website and told not to travel to a conference in Sweden. To underscore the point, the threat included their airline ticket numbers, seat locations and hotel booking.

“It was a mistake for us to think that here, we are safe,” Dolinina told The Associated Press.

The Kremlin, which routinely denies going after its opponents abroad, has been blamed for decades for such attacks.

The most famous cases include Soviet revolutionary-turned-exiled dissident Leon Trotsky, who was killed in 1940 in Mexico after being attacked with an ice ax by a Soviet agent, and Georgi Markov, a dissident working for the BBC's Bulgarian language service, who died in 1978 in London after being jabbed with a poison-tipped umbrella.

Britain was the site of other poisonings blamed on Russian security services under Putin. Defector and former intelligence officer Alexander Litvinenko died after drinking tea laced with radioactive polonium-210 in 2006, and former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter fell gravely ill but recovered following an attack with a Soviet-era nerve agent in 2018. The Kremlin repeatedly denied involvement in the British cases.

Now, with a full-scale domestic crackdown underway inside Russia, most of the Kremlin's political opponents, independent journalists and activists have moved abroad. There are strong suspicions, as well as accusations from officials, that Moscow is increasingly targeting them.

The breadth of those individuals pursued by Russia, “even if they look and sound completely insignificant,” is because Russian authorities believe they “might come back to the country and destroy it completely,” said security expert Andrei Soldatov.

There are multiple reports of exiles being persecuted not only in former Soviet countries with a large Russian diaspora but also in Europe and beyond.

Activists and independent journalists have reported symptoms that they suspect to be poisoning.

Investigative journalist Elena Kostyuchenko fell ill on a train from Munich to Berlin in 2022, and German prosecutors later said they were investigating it as an attempted killing.

Natalia Arno, the head of the U.S.-based Free Russia Foundation, told AP she still suffers from nerve damage after a suspected poisoning in Prague in May. She believes Russian security services tried to “silence” her because of her pro-democracy work.

In an especially brutal incident, the bullet-riddled body of pilot Maksim Kuzminov was found in La Cala, Spain, near the eastern port of Alicante, after being shot and run over with a car. Threats against him surfaced soon after he stole a Russian Mi-8 helicopter in August, flew it to Ukraine and defected.

Kuzminov, 33, became a “moral corpse” the moment he planned his “dirty and terrible crime,” said Sergei Naryshkin, head of Russia’s foreign intelligence service.

In March, Leonid Volkov, chief of staff to the late opposition politician Alexei Navalny, had his arm broken in a hammer attack in the Lithuanian capital Vilnius.

Lithuania's security service said the assault was probably “Russian-organized and implemented." On April 19, Polish police detained two people on suspicion of attacking Volkov on the orders of a foreign intelligence service.

In the decades Putin has held power, the Kremlin has denied multiple times that it is targeting its enemies at home and abroad. It has not commented on the suspected poisonings and Putin's spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, declined comment on Volkov's case, saying it was a matter for Lithuania's Interior Ministry.

Even fledgling anti-war groups find themselves in Moscow's sights.

Russians in Stockholm, Sweden, who in May 2022 formed one of the first organizations to support Ukraine and political prisoners, burned an effigy of Putin labeled “war criminal” outside the Russian Embassy.

Six months later, Russian authorities designated the group an undesirable organization, threatening members with fines and prison. Their relatives were visited at home in Russia by police, and their personal data was leaked, members told AP, speaking on condition of anonymity because of fears for their security.

The Russian Orthodox Tsargrad media outlet suggested the group’s members could be recruited by foreign intelligence services and dubbed them “terrorists.” The pro-Kremlin outlet warned them of a nasty surprise if they continued opposing the war.

Days later, while visiting relatives in St. Petersburg, a group member named Marina said a police car stopped right in front of her as she exited a shop. Three men got out, asked for her documents, forced her into the car and drove to a police station, siren blaring.

“It was really scary. How the hell did they know my exact location?” Marina told AP, declining to give her surname because she fears for her safety.

She was confronted with the leaked data and video of the embassy protest, and investigators demanded she identify other members of the group, reveal its funding source and asked her views on the war. One even questioned why she was leaving Russia before her father’s birthday -– making clear they knew the identity of her family.

She was charged with an administrative violation, usually punishable by a fine. As police prepared to drive her to her parents’ apartment, it was suggested she “cooperate” and become an informant if she wanted to see her family again without fear of detention, Marina said.

“It’s a known modus operandi for Russian intelligence and the Russian regime to follow opponents in the Russian diaspora in other countries and subject them to different types of harassment or intelligence work,” Fredrik Hultgren-Friberg, spokesperson for the Swedish Security Service, told AP.

Soldatov said the Kremlin is going after a wide range of opponents because it fears pro-Western uprisings like those in Georgia and Ukraine and wants to prevent the seeds of dissent from growing into “something new.”

Even though Western countries expelled hundreds of Russian spies in coordinated actions after the 2018 poisoning of the Skripals and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russians abroad say they are concerned Moscow still can reach them.

Marokhovskaya, the investigative journalist in Prague, received anonymous threats, including one indicating close surveillance that said, “We’ll find her wherever she walks her wheezing dog.”

She and Dolinina told AP they experienced such observation inside Russia, including after publishing award-winning investigations of corruption in Putin’s family.

After moving to Europe, Dolinina said she initially thought she was experiencing “constant paranoia.” When she got the anonymous threats and was followed on Prague's streets, however, she realized the fears were well-founded.

Neither journalist has concrete proof that Russian security services targeted them, but they said they believe the personal data -– flight information, passport numbers and home addresses -– and physical surveillance were likely orchestrated by a state actor.

“I was really shocked that it’s happening in Europe,” Dolinina said.

Although the many incidents the West blames on the Kremlin fuel speculation that Moscow still can intimidate Russians abroad, not everyone has been silenced.

“This is not the reason to quit,“ Marokhovskaya said. "It’s the reason to keep working.”

FILE - Russian defector Maksim Kuzminov attends a news conference in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Tuesday, Sept. 5, 2023. Spanish police say the bullet-riddled body of a man found in a Spanish town was that of Kuzminov, 33, who flew a Russian military helicopter across the front lines into Ukraine last year. Sergei Naryshkin, head of Russia's foreign intelligence service, said Kuzminov became a "moral corpse" from the moment he planned his "dirty and terrible crime." (AP Photo/Vladyslav Musiienko, File)

FILE - Leonid Volkov, chief of staff for the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny watches a session of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France, on Dec. 15, 2021. Volkov had his arm broken by an attacker wielding a hammer in Vilnius, Lithuania, in March. Lithuania's security service said the assault was probably "Russian-organized and implemented." (AP Photo/Jean-Francois Badias, File)

FILE - Yulia Skripal poses during an interview in London, on Wednesday, May 23, 2018. She and her father, Sergei Skripal, were found slumped on a bench in Salisbury, England, in March 2018. Sergei Skripal lived there after being released from prison in Russia in a spy swap. British investigators said they had been poisoned with a Russian-developed nerve agent and blamed Moscow for the attack. Moscow denied the allegations. (Dylan Martinez/Pool via AP, File)

FILE - Police officers guard a supermarket parking facility near where former spy and defector Sergei Skripal and his daughter were found critically ill following exposure to the Russian-developed nerve agent Novichok in Salisbury, England, on Tuesday, March 13, 2018. The British government accused Russia of attempted murder in the poisonings. Two men identified by authorities as carrying out the attack denied any involvement and told Russian television they were simply tourists. (AP Photo/Matt Dunham, File)

FILE – Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko, a former operative for the KGB and FSB, is seen at his home in London, on Friday, May 10, 2002. Litvinenko was viewed as a traitor by the Kremlin after fleeing to Britain in 2000. He died after drinking tea laced with radioactive polonium-210 at a hotel in London. On his deathbed, Litvinenko claimed that Russian President Vladimir Putin directly ordered his assassination. A British inquiry later found that Russian agents had killed Litvinenko, probably with Putin's approval. (AP Photo/Alistair Fuller, File)