Following the publication of “An Appeal for Human Rights” on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta’s historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregationist laws that excluded them from white areas in restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. Hundreds of black people were arrested that year, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., before white leaders relented and desegregated Atlanta’s facilities. Here is a selection of Associated Press photos showing events related to the Atlanta Student Movement against racial inequality and exclusion.

FILE - In this March 16, 1960 file photo, Victor Cobb, right, the manager of a dining room in Atlanta's Trailways Bus Terminal, asks African American sit down demonstrators to leave his lunch counter, in Atlanta. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this May 17, 1960 file photo, state troopers stand guard at the state capitol, in Atlanta awaiting a scheduled march on the building by black demonstrators in observance of the sixth anniversary of the Supreme Court's school desegregation decision. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this May 17, 1960 file photo, a state trooper passes out billy clubs to other troopers as 2,000 blacks started a march toward the state capitol in Atlanta, in observance of the sixth anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court's school desegregation decision. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP PhotoHorace Cort, File)

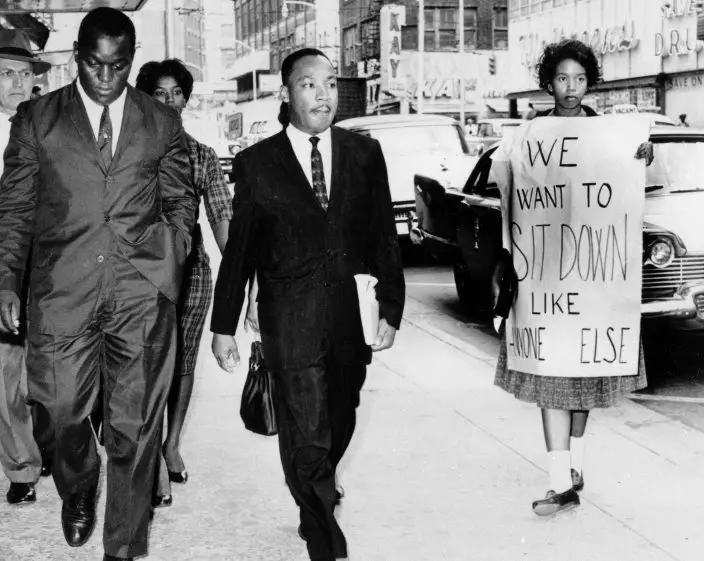

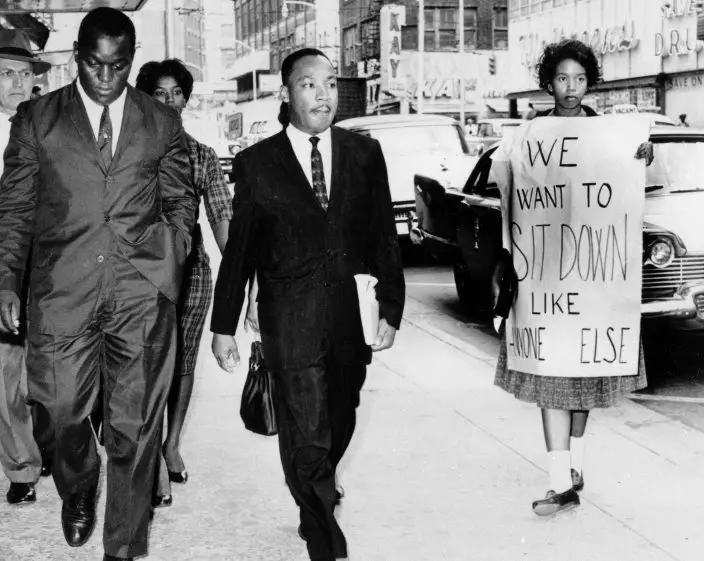

FILE - In this Oct. 19, 1960 file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. under arrest by Atlanta Police Captain R.E. Little, left rear, passes through a picket line outside Rich's Department Store, in atlanta. On King's right are Atlanta Student Movement leader Lonnie King and Spelman College student Marilyn Pryce. Holding the sign is Spelman student activist Ida Rose McCree. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 19, 1960 file photo, Black activists are seen picketing outside Rich's department store protesting against segregated eating facilities at one of its lunch counters in Atlanta, Ga. The activists who had taken seats inside the store were arrested. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 19, 1960 file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., right, looks out the window of a police car as he and Spelman College student Agnes Blondean Orbert, arrested with him at Rich's Department Store, are taken to jail, in Atlanta.. Driving the car is Atlanta Police Capt. R.E. Little. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 25, 1960 file photo, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., integration leader, is escorted from the Atlanta, Ga. jail by two unidentified officers as he is taken to neighboring DeKalb county courthouse for a traffic hearing. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP PhotoHorace Cort, File)

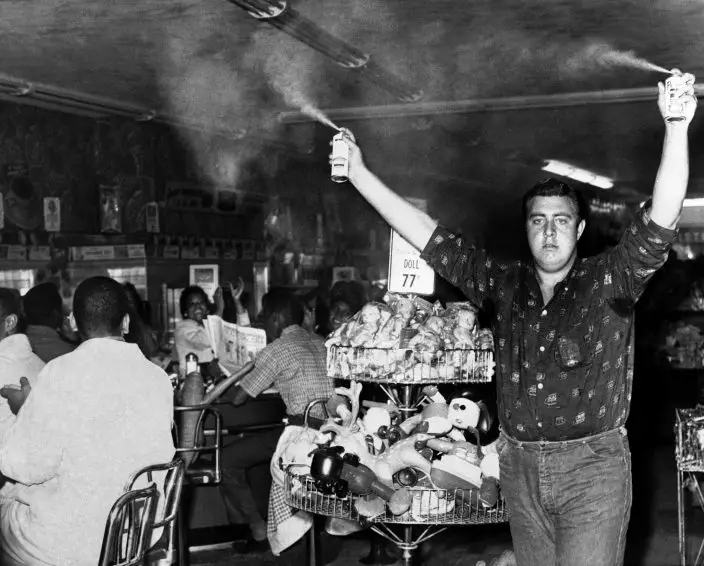

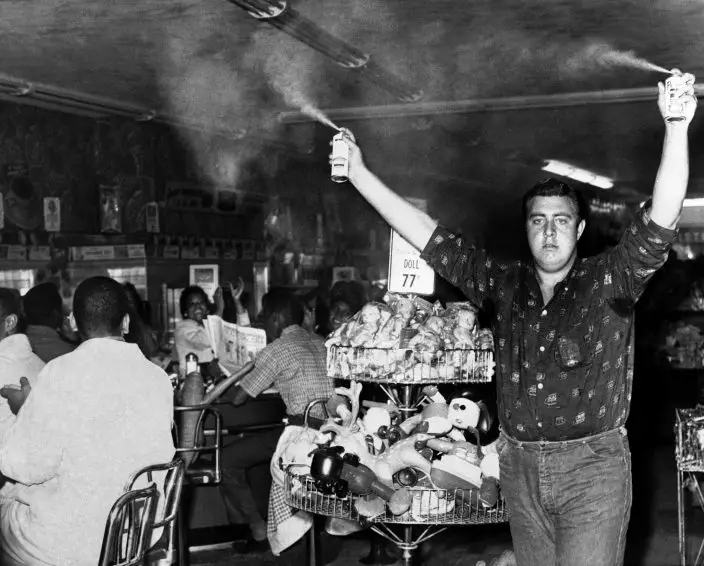

FILE - In this Oct. 20, 1960 file photo, Woolworth's customers closed its main downtown store in Atlanta., after white youth identified as Harold Sprayberry, 21, of Atlanta, walked along lunch counter area spraying insect repellent above heads of nearly 100 African Americans demonstrating at a sit-in for three hours. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP PhotoHorace Cort, file)

FILE - In this Oct. 25, 1960 file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. leaves court after being given a four-month sentence in Decatur, Ga., for taking part in a lunch counter sit-in at Rich's department store. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

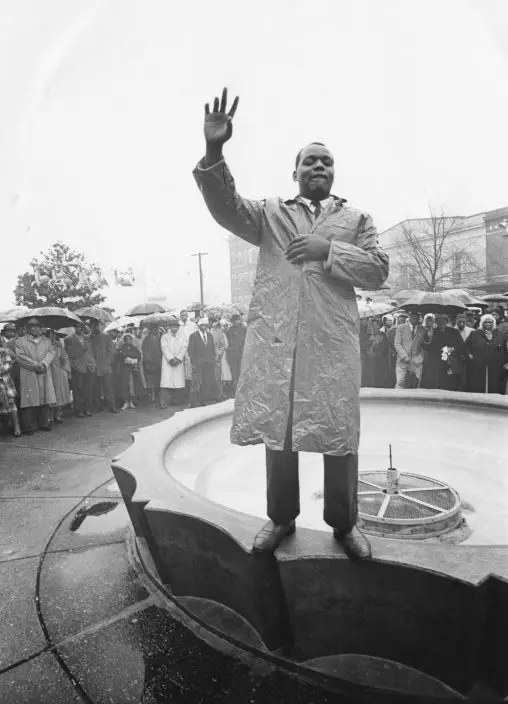

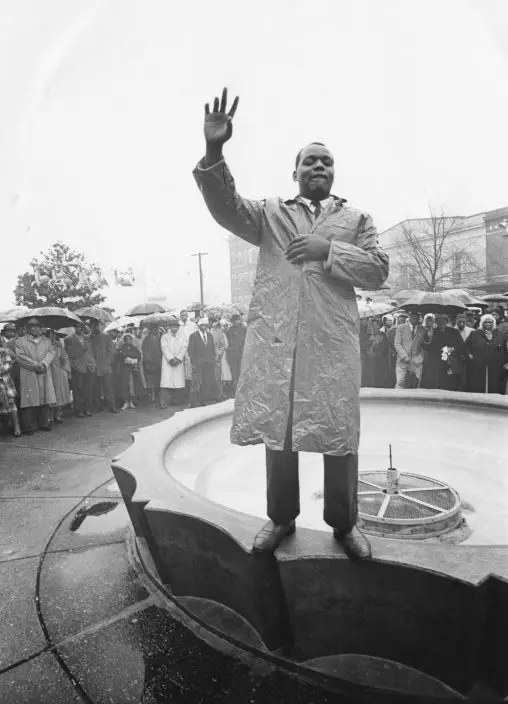

FILE - In this Dec. 12, 1960 file photo, Lonnie King, leader, of the Atlanta Student Movement addresses demonstrators in Atlanta in a group prayer before a protest against retail shops. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

Click to Gallery

FILE - In this March 16, 1960 file photo, Victor Cobb, right, the manager of a dining room in Atlanta's Trailways Bus Terminal, asks African American sit down demonstrators to leave his lunch counter, in Atlanta. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 19, 1960 file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. under arrest by Atlanta Police Captain R.E. Little, left rear, passes through a picket line outside Rich's Department Store, in atlanta. On King's right are Atlanta Student Movement leader Lonnie King and Spelman College student Marilyn Pryce. Holding the sign is Spelman student activist Ida Rose McCree. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 19, 1960 file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., right, looks out the window of a police car as he and Spelman College student Agnes Blondean Orbert, arrested with him at Rich's Department Store, are taken to jail, in Atlanta.. Driving the car is Atlanta Police Capt. R.E. Little. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 25, 1960 file photo, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., integration leader, is escorted from the Atlanta, Ga. jail by two unidentified officers as he is taken to neighboring DeKalb county courthouse for a traffic hearing. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP PhotoHorace Cort, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 20, 1960 file photo, Woolworth's customers closed its main downtown store in Atlanta., after white youth identified as Harold Sprayberry, 21, of Atlanta, walked along lunch counter area spraying insect repellent above heads of nearly 100 African Americans demonstrating at a sit-in for three hours. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP PhotoHorace Cort, file)

FILE - In this March 16, 1960 file photo, Victor Cobb, right, the manager of a dining room in Atlanta's Trailways Bus Terminal, asks African American sit down demonstrators to leave his lunch counter, in Atlanta. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this May 17, 1960 file photo, state troopers stand guard at the state capitol, in Atlanta awaiting a scheduled march on the building by black demonstrators in observance of the sixth anniversary of the Supreme Court's school desegregation decision. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this May 17, 1960 file photo, a state trooper passes out billy clubs to other troopers as 2,000 blacks started a march toward the state capitol in Atlanta, in observance of the sixth anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court's school desegregation decision. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP PhotoHorace Cort, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 19, 1960 file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. under arrest by Atlanta Police Captain R.E. Little, left rear, passes through a picket line outside Rich's Department Store, in atlanta. On King's right are Atlanta Student Movement leader Lonnie King and Spelman College student Marilyn Pryce. Holding the sign is Spelman student activist Ida Rose McCree. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 19, 1960 file photo, Black activists are seen picketing outside Rich's department store protesting against segregated eating facilities at one of its lunch counters in Atlanta, Ga. The activists who had taken seats inside the store were arrested. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 19, 1960 file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., right, looks out the window of a police car as he and Spelman College student Agnes Blondean Orbert, arrested with him at Rich's Department Store, are taken to jail, in Atlanta.. Driving the car is Atlanta Police Capt. R.E. Little. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 25, 1960 file photo, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., integration leader, is escorted from the Atlanta, Ga. jail by two unidentified officers as he is taken to neighboring DeKalb county courthouse for a traffic hearing. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP PhotoHorace Cort, File)

FILE - In this Oct. 20, 1960 file photo, Woolworth's customers closed its main downtown store in Atlanta., after white youth identified as Harold Sprayberry, 21, of Atlanta, walked along lunch counter area spraying insect repellent above heads of nearly 100 African Americans demonstrating at a sit-in for three hours. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP PhotoHorace Cort, file)

FILE - In this Oct. 25, 1960 file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. leaves court after being given a four-month sentence in Decatur, Ga., for taking part in a lunch counter sit-in at Rich's department store. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Dec. 12, 1960 file photo, Lonnie King, leader, of the Atlanta Student Movement addresses demonstrators in Atlanta in a group prayer before a protest against retail shops. Following the publication of "An Appeal for Human Rights" on March 9, 1960, students at Atlanta's historically black colleges waged a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins protesting segregation at restaurants, theaters, parks and government buildings. (AP Photo, File)

Five years ago, video images from a Minneapolis street showing a police officer kneeling on the neck of George Floyd as his life slipped away ignited a social movement.

Now, videos from another Minneapolis street showing the last moments of Renee Good's life are central to another debate about law enforcement in America. They've slipped out day by day since ICE agent Jonathan Ross shot Good last Wednesday in her maroon SUV. Yet compared to 2020, the story these pictures tell is murkier, subject to manipulation both within the image itself and the way it is interpreted.

This time, too, the Trump administration and its supporters went to work establishing their own public view of the event before the inevitable imagery appeared.

But half a decade later, so many things are not the same — from cultural attitudes to rapidly evolving technology around all kinds of imagery.

“We are in a different time,” said Francesca Dillman Carpentier, a University of North Carolina journalism professor and expert on the media's impact on audiences.

No one who saw the searing video of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin with his knee on Floyd's neck for more than nine minutes on May 25, 2020, is likely to forget it — and Chauvin's impassive face Floyd insisted he couldn't breathe. United in revulsion, demonstrators began one of the nation's largest-ever social movements. Chauvin was convicted of murder.

The footage “caused many individuals to experience an epiphany about racism, specifically cultural racism, in the United States,” legal scholar Angela Onwuachi-Willig wrote in a Houston Law Review study that examined whether white Americans experienced a collective cultural trauma.

She eventually concluded that didn't happen and that the impact diminished with time. The rollback of diversity programs with the second Trump administration offers evidence for her argument.

“The people who are writing the cultural narrative of the Good shooting took notes from the Floyd killing and are managing this narrative differently,” said Kelly McBride, an expert on media ethics for the Poynter Institute.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem labeled Good, who was demonstrating in opposition to ICE enforcement of immigration laws, a domestic terrorist — an interpretation that Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey dismissed with an expletive. Both President Donald Trump and Vice President JD Vance suggested the shooting was justified because Good was trying to run Ross down with her vehicle.

On the night of the killing, White House border czar Tom Homan was cautious in an interview with the “CBS Evening News” when anchor Tony Dokoupil showed him the most widely distributed video of the incident, taken by a bystander and posted by a reporter for the Minnesota Reformer. The veteran law enforcement official said it would be unprofessional for him to prejudge before an investigation.

Later that evening, Homan issued a statement calling the shooting “another example of the results of the hateful rhetoric and violent attacks” against U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Border Patrol officers.

Video of the incident has been generally inconclusive about whether Good's vehicle actually hit Ross before he opened fire. Even if she did, many experts question whether that represented grounds for firing his weapon. Clearly, however, that would bolster public sympathy for the officer.

“These ICE videos do present irrefutable facts — a woman drove her car and then she was shot dead by an ICE agent,” said Duy Linh Tu, a documentarian and professor at the Columbia University journalism school. “What the videos can't show is the intent of the woman or the officer. And that's the tricky part.”

Good, obviously, can’t speak to what motivated her to put her SUV in drive and move on Portland Avenue South.

Several news organizations have carefully examined the forensic evidence that has emerged. The Associated Press wrote that it was unclear if Good's car made contact with Ross. The Washington Post wrote that “videos examined by The Post, including one shared on Truth Social by Trump, do not clearly show whether the agent is struck or how close the front of the vehicle comes to striking him.”

The New York Times said that “in one video, it looks like the agent is being struck by the SUV. But when we synchronize it with the first clip, we can see the agent is not being run over.”

Video that emerged Friday from the Minnesota site Alpha News showed the incident from Ross' perspective. It, too, left many questions and no shortage of people willing to answer them.

Vance linked to the video online and wrote: “Many of you have been told this law enforcement officer wasn't hit by a car, wasn't being harassed and murdered an innocent woman. The reality is that his life was endangered and he fired in self-defense.”

Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer wrote online that “how could anyone on the planet watch this video and conclude what JD Vance says?” Schumer said the administration “is lying to you.”

When one online commentator wrote that Good did not deserve to be shot in the face, conservative media figure Megyn Kelly responded, “Yes, she did. She hit and almost ran over a cop.”

Poynter’s McBride said the media has generally done a good and careful job outlining the evidence that is circulating around in the public. But the administration has also been effective in spreading its interpretation, she said.

There are more camera angles available now than there was with Floyd, but “I don't know if that adds clarity or more fog to this case,” Tu said. “I think that people will see what they want to see. Or, rather, they'll pick the angle that aligns with what they already believe.”

That nagging sense of uncertainty left by the videos leaves experts like Tu and Carpentier to conclude they will pale in impact compared to the Floyd case. With each passing year, the public is becoming more desensitized to images of violence — as the online spread of footage showing Republican activist Charlie Kirk illustrated, she said.

The spread of AI-enhanced fake images is also teaching the public to question what it sees, she said. Before Ross was identified, BBC Verify said false images were being spread online speculating about what the masked agent looked like, and fake video of a Minneapolis demonstration spread.

“Now you can't believe what you're seeing,” Carpentier said. “You don't know if what you're seeing is the real video or if it has been doctored. I don't think AI is being a friend in this case at all.”

David Bauder writes about the intersection of media and entertainment for the AP. Follow him at http://x.com/dbauder and https://bsky.app/profile/dbauder.bsky.social.

Federal immigration officers make an arrest as bystanders film the incident Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/John Locher)

Bystanders film a federal immigration officer in their car Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/John Locher)