Tom Cheeseman's phone rang at 3 a.m. Friday, soon after returning home from one of the worst days he's seen in 30 years as a Brooklyn funeral director.

He just chauffeured the deceased for 12 hours — some coronavirus victims, some not — between houses, hospitals and funeral homes. But the call came: Another death. Another pick up. And so out he went, determined to help another person reach their final resting place with as much dignity as the situation would allow.

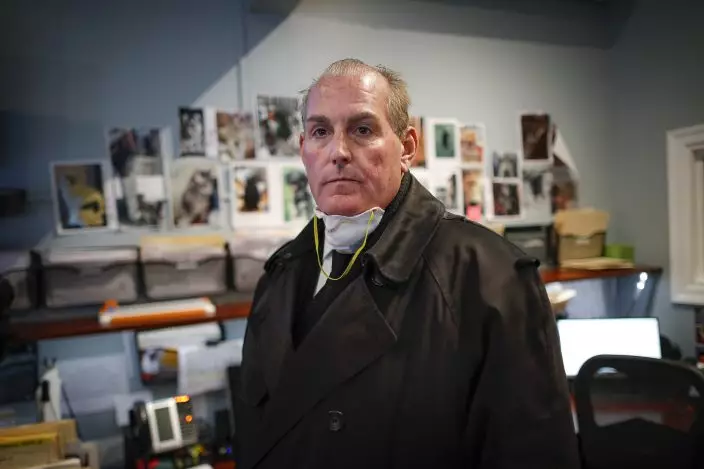

“We took a sworn oath to protect the dead, this is what we do,” he said. “We’re the last responders. Our job is just as important as the first responders."

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman talks on the phone after making a house call to collect a body for transfer to a mortuary, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. “We took a sworn oath to protect the dead, this is what we do,” he said. “We’re the last responders. Our job is just as important as the first responders." (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

He pulled into Daniel J. Schaefer funeral home around 8:20 a.m. on about three hours of sleep. His first act, he thought, would be to resolve unfinished business from the day before.

Twice on Thursday, he had been called to hospitals, only to be told by staff that the remains he sought couldn’t be found in the refrigerated trailers serving as makeshift morgues — that's in addition to the 10 bodies he did pick up. The coronavirus pandemic has crunched New York City’s medical system, and that has left a mighty weight on the 52-year-old’s broad shoulders.

“This is terrible,” he said. “I had tears in my eyes.”

Medical workers step over bodies as they search a refrigerated trailer at Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

He walked into the funeral home office — a room with five desks buried in paperwork, phones ringing ceaselessly — and realized immediately the hospitals would have to wait. House calls take precedent — bodies can’t be left there too long. And a long list was already building.

“Our plans that were laid out, they’re all changed,” he said.

9:20 A.M.

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman collects a body from a nursing home, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. He wears the shades for every call, even when it’s gray and rainy. He likes that light seeps into his peripheral vision, no matter how dreary. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

Cheeseman parked near the apartment building in his Dodge minivan, which has tinted windows to keep his cargo private. EMTs were on site and had already pronounced the death, but he had to wait for a colleague.

He placed a sign on his dashboard — “Emergency Funeral Service Vehicle" — and stepped out of the van. A burly, imposing figure at 6-foot-5, Cheeseman is dressed like an early Tarantino character. White shirt, black tie, black suit, black trench, and as always, black sunglasses.

He wears the shades for every call, even when it’s gray and rainy. He likes that light seeps into his peripheral vision, no matter how dreary.

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman and a colleague wear personal protective equipment due to COVID-19 concerns after delivering a body to a funeral home, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Cheeseman is picking up as many as 10 bodies per day. Most bodies come from homes and hospitals. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

“I see sun every day,” he said.

His associate arrived around 9:45 a.m. and pulled a gurney from the Dodge. Cheeseman put on an N95 facemask and gloves, tucked a plastic-wrapped white sheet under his arm, and helped wheel the gurney toward the apartment entrance.

They emerged 15 minutes later and loaded the body into the Dodge. Cheeseman removed the mask and gloves, sanitized his hands and set off for a Jewish funeral home requested by the widow.

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman puts on protective gloves due to COVID-19 concerns as he delivers a body to a funeral home, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. “We took a sworn oath to protect the dead, this is what we do,” he said. “We’re the last responders. Our job is just as important as the first responders." (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

10:15 A.M.

Another director called during Cheeseman's drive, a longtime friend. They commiserated about the past week, when the pandemic began to put the funeral industry into crisis, and looked forward to beers on the beach later in the summer.

Cheeseman has been at this for nearly his entire adult life.

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman puts on a protective mask due to COVID-19 concerns before making a house call to collect a body, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. The Associated Press spent a day on the road with a Brooklyn funeral director overwhelmed by demand due to the coronavirus outbreak. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

He had some affinity for funerals as a child — “Everybody in the room is dressed as if it’s a party, including the person in the box,” he said. His father, a homicide detective, let him watch an autopsy as a teen, and the dead body didn't make him nervous or nauseous.

So when a family friend offered him a job at his funeral home a few years later, he gave it a try.

“This is God’s plan for me,” he said.

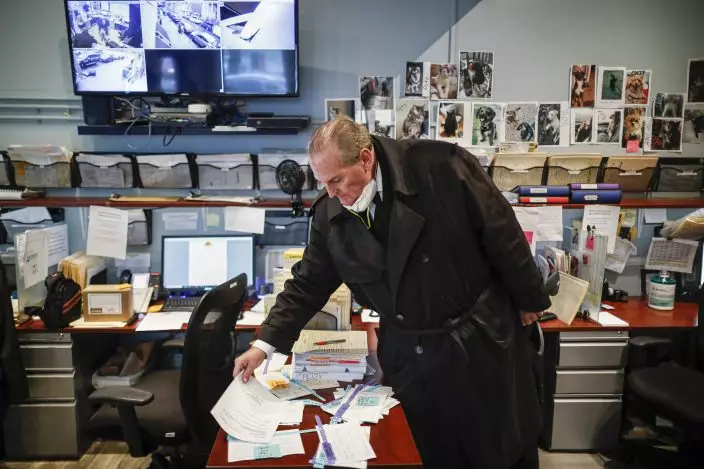

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman sorts through a new pile of body collection slips that accumulated throughout his workday at his office, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

The Dodge pulled into the Jewish funeral home in Brooklyn at 10:35 a.m. The director met Cheeseman in the driveway.

“Is this one COVID?” he asks off the bat.

No, Cheeseman answers. Died peacefully in the night.

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman, right, speaks to police officers before making a house call to collect a body, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

10:45 A.M.

Three pickups follow in similar fashion — two from homes, one from a rehab facility.

Those who die at home are less likely to have been tested for the new coronavirus, and many death certificates are listing the cause as pneumonia, with a note for “possible COVID-19." It reminds Cheeseman of the AIDS crisis, when the deceased were listed with similarly uncertain causes.

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman, center, and a colleague make a house call to collect a body, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Cheeseman is picking up as many as 10 bodies per day. Most bodies come from homes and hospitals. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

“I’m treating everybody like it’s a virus case,” he said.

2:15 P.M.

The next stop is Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, where Cheeseman spent an hour and 20 minutes Thursday waiting for hospital police to locate a body. He left empty handed.

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman, center, and a colleague deliver a body to a funeral home, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Cheeseman is picking up as many as 10 bodies per day. Most bodies come from homes and hospitals. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

Remains had been piled into a refrigerated trailer — Cheeseman estimated at least 40 bodies in each — and the mounds of corpses had become difficult to navigate. Cheeseman said he became enraged and made a scene.

“This guy’s in there climbing over people,” he said. “They pointed to the trailer, and I said, ‘I’m not a mountain lion. I don’t climb in there.’”

Kingsbrook called him Friday morning and said they were changing protocols. He could call two hours before each pick up and someone would relocate the needed remains to the hospital morgue.

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman retrieves a body on a house call, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Cheeseman is picking up as many as 10 bodies per day. Most bodies come from homes and hospitals. (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

Pulling into Kingsbrook, he wasn't immediately encouraged. The giant coolers could still be seen from the street. One body sat on a gurney outside, wrapped in a white body bag. More were easily visible on the trailer floor, hospital staff stepping over them.

Cheeseman went in a side door, confirmed paperwork with administrative staff and headed to the morgue. The body was there as promised, held in a traditional silver cooler.

The experience, he said, was “like night and day.”

Funeral director Tom Cheeseman stands in his office during a long workday, Friday, April 3, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. “We took a sworn oath to protect the dead, this is what we do,” he said. “We’re the last responders. Our job is just as important as the first responders." (AP PhotoJohn Minchillo)

“At least now we can call the family back and let them know, put their mind to ease that they are in our care," he said. “So that’s our gratification today.”

4:40 P.M.

Cheeseman made one more pickup — the sixth of eight on Friday — at a senior housing facility and headed back to the Schaefer home. He wheeled the bodies inside, then lumbered exhausted into the office.

For the moment, he stood amid the frantic staff and thumbed through the paperwork.

“Just look at everybody in their eyes and you’ll see how mentally exhausted they truly are,” he said.

“There is no catching up."

Follow Jake Seiner: https://twitter.com/Jake_Seiner