Panic attacks, trouble breathing, relapses that have sent her to bed for 14 hours at a time: At 35, Marissa Oliver has been forced to deal with the specter of death on COVID-19′s terms, yet conversations about her illness, fear and anxiety haven’t been easy.

That’s why she headed onto Zoom to attend a Death Cafe, a gathering of strangers willing to explore mortality and its impact on the living, preferably while sipping tea and eating cake.

“In the Death Cafe, no one winces,” said Oliver, who was diagnosed with the virus in March. “Now, I’m writing down everything in my life that I want to achieve.”

In this June 22, 2020 photo, Marissa Oliver, a COVID-19 survivor who found comfort discussing her experience with the virus and fear of death at Death Cafe meetups, walks through a park in her neighborhood in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Others attending virtual Death Cafes, part of a broader "death-positive" movement to encourage more open discussion about grief, trauma and loss, are coping with deaths from COVID-19, cancer and other illnesses. (AP PhotoEmily Leshner)

Death Cafes, part of a broader “death-positive” movement to encourage more open discussion about grief, trauma and loss, are held around the world, in nearly 100 countries. While many haven’t migrated online in the pandemic, others have.

The global virus toll and the social isolation it has extracted have opened old, unresolved wounds for some. Others attending virtual Death Cafes are coping with fresh losses from COVID-19, cancer and other illness. Still more bring metaphorical death to the circles: The end of friendships, shattered romances or chronic illness, as Oliver has endured.

At one recent virtual Death Cafe, a 33-year-old man spoke of refusing to pack up his wife’s belongings six months after her death from cancer. A woman who underwent a heart transplant 31 years ago described her peace with the decision not to have another, as her donated organ deteriorates.

This Nov. 16, 2019 photo shows an altar made by mortician and death cafe host Angela Craig-Fournes in honor of Death Cafe founder Jon Underwood, who died in 2017. (Angela Craig-Fournes via AP)

For Jen Carl in Washington, D.C., the pandemic has intensified memories of her 11 years of sexual abuse as a child, her father’s drug and alcohol abuse, and his death about six years ago. She said sharing and listening to the stories of others in Death Cafes have helped.

“I feel just really so at peace and relieved when I’m in circles where folks are talking about real things in life and not trying to move away from the uncomfortable,” Carl told a recent group.

“I’ve been on a couple of Zoom calls with close friends who aren’t worried about talking about difficult things most of the time but then when COVID’S come up it’s like, `Oh well, we’re partying right now. Let’s not talk about that,′ and that just triggers me so much.”

In this June 22, 2020 photo, Marissa Oliver, a COVID-19 survivor who found comfort discussing her experience with the virus and fear of death at Death Cafe meetups, walks through a park in her neighborhood in the Brooklyn borough of New York. Others attending virtual Death Cafes, part of a broader "death-positive" movement to encourage more open discussion about grief, trauma and loss, are coping with deaths from COVID-19, cancer and other illnesses. (AP PhotoEmily Leshner)

Inspired by Swiss sociologist and anthropologist Bernard Crettaz, who organized his first “cafe mortel” in 2004, the late British web developer Jon Underwood honed the model and held the first Death Cafe in his London home in 2011. The idea spread quickly and the meetups in restaurants and cafes, homes and parks now span Europe and North America, reaching into Australia, the Caribbean and Japan.

Underwood died suddenly as a result of undiagnosed leukemia in 2017, but his wife and other relatives have carried on. They maintain a website, Deathcafe.com, where hosts post their gatherings.

One important difference between Death Cafes and traditional support and bereavement groups is the range of stories. But the cafes also offer the freedom to approach the room with levity rather than stern seriousness, and extraordinary diversity: a mix of races, genders and ages, from people in the moment with terminal loved ones to those who have lost classmates or relatives to suicide.

Death Cafes aren’t intended to “fix” problems and find solutions but to foster sharing as the road to support. They’re generally kept to 30 or so, meet monthly and also include the “death curious,” people who aren’t dealing with loss but choose to take on the topic anyway.

Psychotherapist Nancy Gershman, who specializes in grief and loss, has been hosting Death Cafes in New York since they made their way to the U.S. in 2013.

“Death Cafes are a place where strangers meet to talk about things regarding death and dying that they can’t bring anywhere else, that they can’t bring home or to co-workers or to best friends,” she said.

Registered nurse Nicole Heidbreder is a birth and end-of-life doula. She also trains others as doulas and has been hosting Death Cafes in Washington, D.C., for about five years.

“I was working as a full-time hospice nurse and I very quickly recognized how many families I was sitting with whom this was their very first time talking about the end of life. I just felt it was such an absolute shame,” Heidbreder said.

“One of the parallels between birth and death is that a little more than 100 years ago in our country, all of us would have been very well versed in what birth and death literally looked like," she said. "We would have seen our family and neighbors do the tasks of tending to people who are giving birth or families who are losing someone. And now we simply aren’t exposed to that.”

Heidbreder said the coronavirus has changed the conversation yet again. She said she shifted to offering the virtual cafes “on a weekly basis at the time of peak COVID in the country.”

She now hosts people not just in the D.C. area, as she did before the pandemic, but across America, from California to North Carolina. More health care workers have shown up, too.

J. Dana Trent is a professor of world religions at Wake Tech Community College in Raleigh, North Carolina. She served as a hospital chaplain in a death ward at age 25 after graduating from divinity school, assisting in 200 deaths in a year.

The ordained Southern Baptist minister used her experiences in the hospital for a 2019 book, “Dessert First: Preparing for Death While Savoring Life,” which offers a view of how “positive death” can be achieved.

“COVID has certainly brought death to the forefront. It has brought the death-positive movement to the forefront, but we’re still scared,” Trent said. “What I’m grateful for is that COVID has awakened society to the possibility of death. None of us is getting out of here alive.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through the Religion News Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Follow Leanne Italie on Twitter at https:twitter.com/litalie and Emily Leshner at https:twitter.com/leshnerd

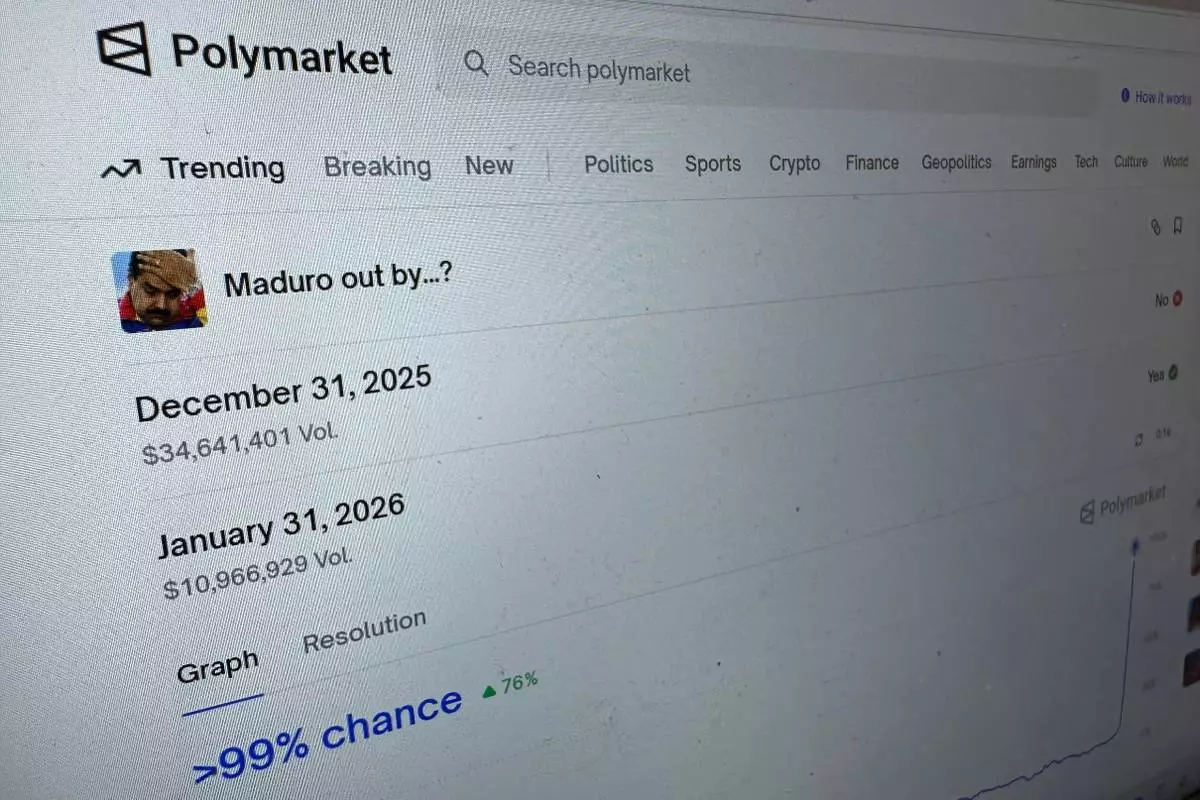

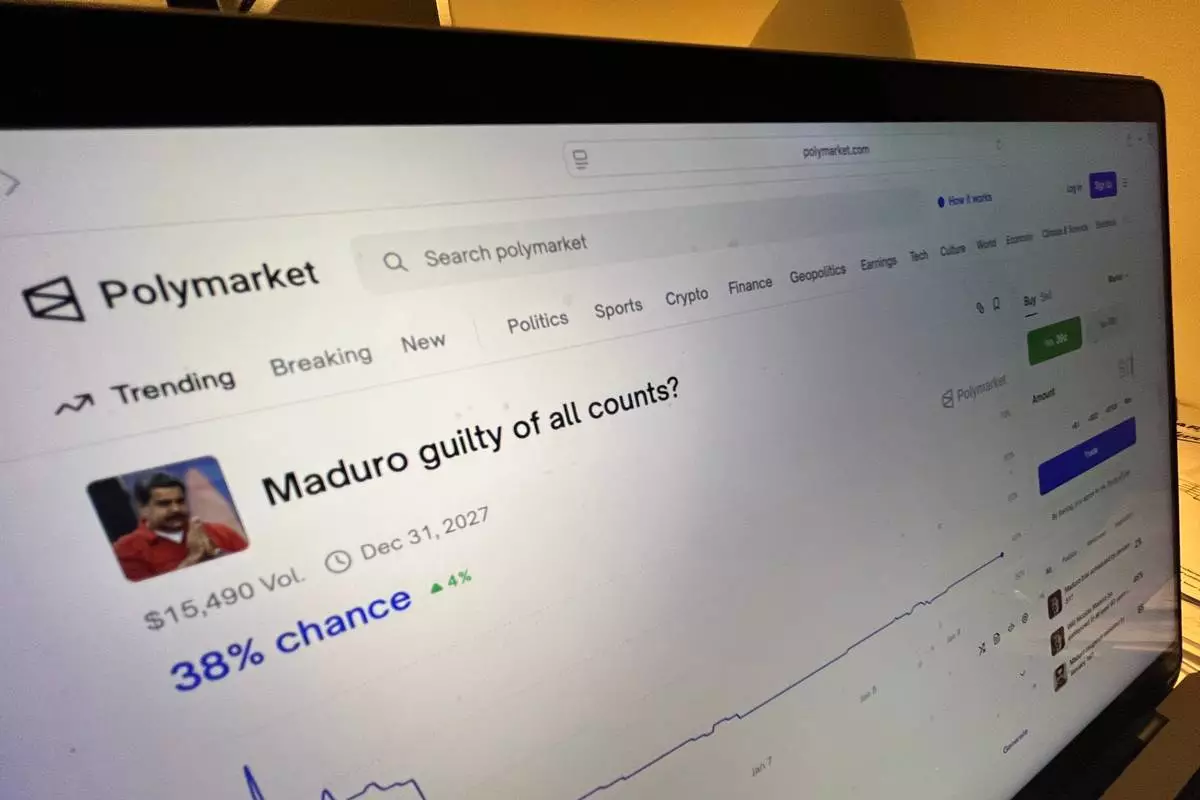

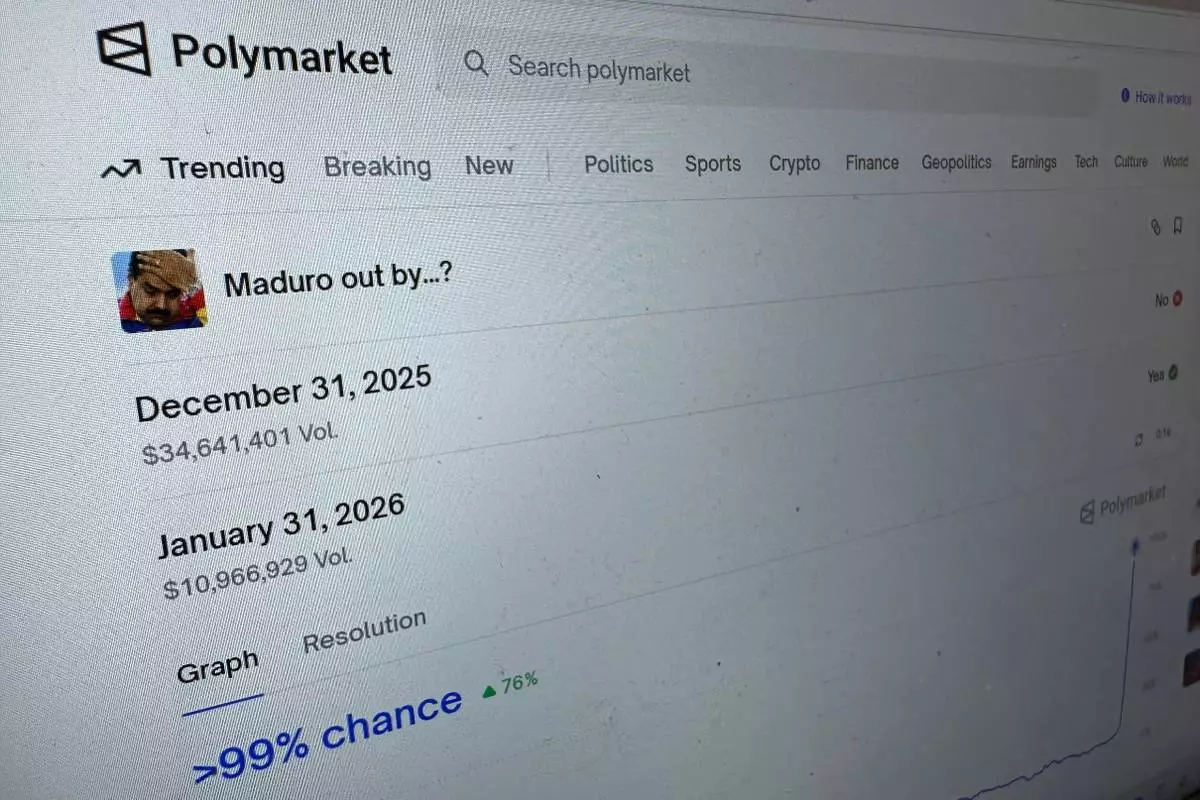

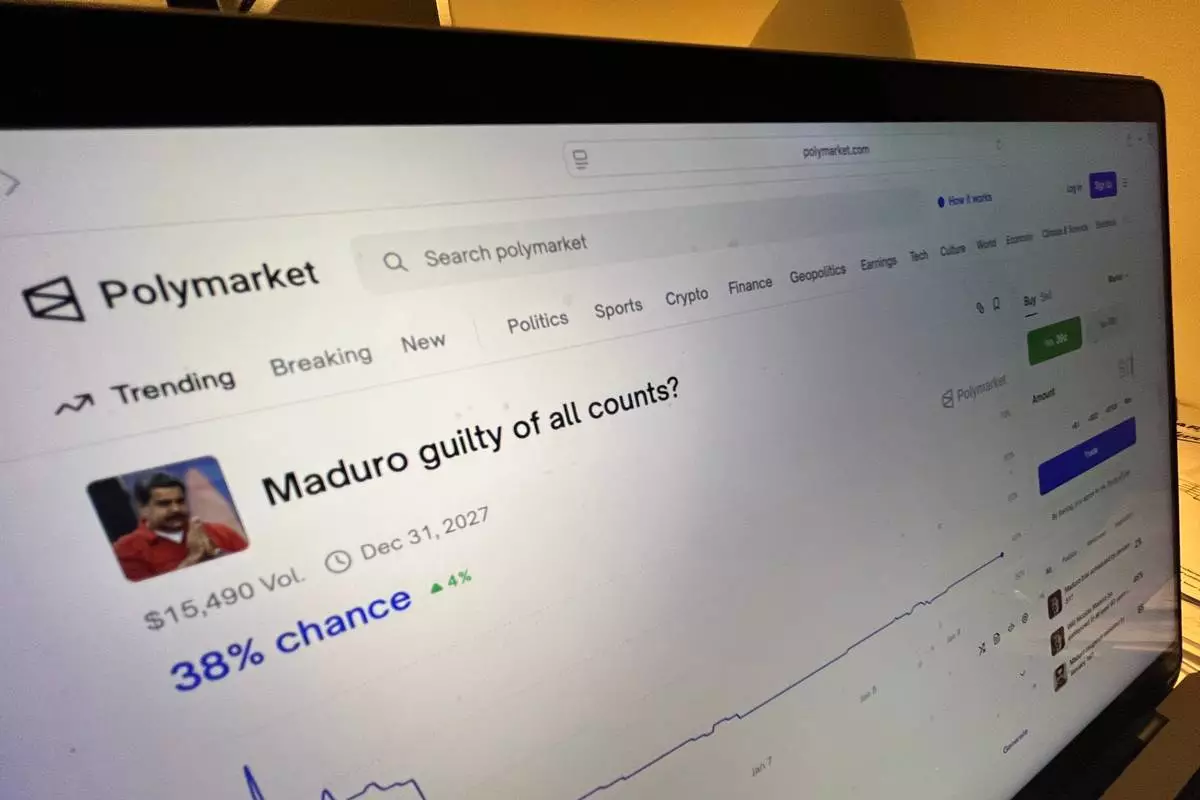

Prediction markets let people wager on anything from a basketball game to the outcome of a presidential election — and recently, the downfall of former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

The latter is drawing renewed scrutiny into this murky world of speculative, 24/7 transactions. Last week, an anonymous trader pocketed more than $400,000 after betting that Maduro would soon be out of office.

The bulk of the trader’s bids on the platform Polymarket were made mere hours before President Donald Trump announced the surprise nighttime raid that led to Maduro’s capture, fueling online suspicions of potential insider trading because of the timing of the wagers and the trader’s narrow activity on the platform. Others argued that the risk of getting caught was too big, and that previous speculation about Maduro’s future could have led to such transactions.

Polymarket did not respond to requests for comment.

The commercial use of prediction markets has skyrocketed in recent years, opening the door for people to wage their money on the likelihood of a growing list of future events. But despite some eye-catching windfalls, traders still lose money everyday. And in terms of government oversight in the U.S., the trades are categorized differently than traditional forms of gambling — raising questions about transparency and risk.

Here's what we know:

The scope of topics involved in prediction markets can range immensely — from escalation in geopolitical conflicts, to pop culture moments and even the fate of conspiracy theories. Recently, there’s been a surge of wages on elections and sports games. But some users have also bet millions on things like a rumored — and ultimately unrealized — “secret finale” for the Netflix’s “Stranger Things,” whether the U.S. government will confirm the existence of extraterrestrial life and how much billionaire Elon Musk might post on social media this month.

In industry-speak, what someone buys or sells in a prediction market is called an “event contract.” They're typically advertised as “yes” or “no” wagers. And the price of one fluctuates between $0 and $1, reflecting what traders are collectively willing to pay based on a 0% to 100% chance of whether they think an event will occur.

The more likely traders think an event will occur, the more expensive that contract will become. And as those odds change over time, users can cash out early to make incremental profits, or try to avoid higher losses on what they’ve already invested.

Proponents of prediction markets argue putting money on the line leads to better forecasts. Experts like Koleman Strumpf, an economics professor at Wake Forest University, think there’s value in monitoring these platforms for potential news — pointing to prediction markets’ past success with some election outcomes, including the 2024 presidential race.

Still, it's never a “crystal ball,” he noted, and prediction markets can be wrong, too.

Who is behind all of the trading is also pretty murky. While the companies running the platforms collect personal information of their users in order to verify identities and payments, most people can trade under anonymous pseudonyms online — making it difficult for the public to know who is profiting off many event contracts. In theory, people investing their money may be closely following certain events, but others could just be randomly guessing.

Critics stress that the ease and speed of joining these 24/7 wagers leads to financial losses everyday, particularly harming users who may already struggle with gambling. The space also broadens possibilities for potential insider trading.

Polymarket is one of the largest prediction markets in the world, where its users can fund event contracts through cryptocurrency, debit or credit cards and bank transfers.

Restrictions vary by country, but in the U.S., the reach of these markets has expanded rapidly over recent years, coinciding with shifting policies out of Washington. Former President Joe Biden was aggressive in cracking down on prediction markets and following a 2022 settlement with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Polymarket was barred from operating in the country.

That changed under Trump late last year, when Polymarket announced it would be returning to the U.S. after receiving clearance from the commission. American-based users can now join a platform “waitlist.”

Meanwhile, Polymarket’s top competitor, Kalshi, has been a federally-regulated exchange since 2020. The platform offers similar ways to buy and sell event contracts as Polymarket — and it currently allows event contracts on elections and sports nationwide. Kalshi won court approval just weeks before the 2024 election to let Americans put money on upcoming political races and began to host sports trading about a year ago.

The space is now crowded with other big names. Sports betting giants DraftKings and FanDuel both launched prediction platforms last month. Online broker Robinhood is widening its own offerings. Trump’s social media site Truth Social has also promised to offer an in-platform prediction market through a partnership with Crypto.com — and one of the president’s sons, Donald Trump Jr., holds advisory roles at both Polymarket and Kalshi.

“The train has left the station on these event contracts, they’re not going away,” said Melinda Roth, a visiting associate professor at Washington and Lee University’s School of Law.

Because they’re positioned as selling event contracts, prediction markets are regulated by the CFTC. That means they can avoid state-level restrictions or bans in place for traditional gambling and sports betting today.

“It’s a huge loophole,” said Karl Lockhart, an assistant professor of law at DePaul University who has studied this space. “You just have to comply with one set of regulations, rather than (rules from) each state around the country.”

Sports betting is taking center stage. There are a handful of big states — like California and Texas, for example — where sports betting is still illegal, but people can now wager on games, athlete trades and more through event contracts.

A growing number of states and tribes are suing to stop this. And lawyers expect litigation to eventually reach the U.S. Supreme Court, as added regulations from the Trump administration seem unlikely.

Federal law bars event contracts related to gaming as well as war, terrorism and assassinations, Roth said, which could put some prediction market trades on shaky ground, at least in the U.S. But users might still find ways to buy certain contracts while traveling abroad or connecting to different VPNs.

Whether the CFTC will take any of that on has yet to be seen. But the agency, which did not respond to request for comment, has already taken steps away from enforcement.

Despite overseeing trillions of dollars for the overall U.S. derivatives market, the CFTC is also much smaller than the Securities and Exchange Commission. And at the same time event contracts are growing rapidly on prediction market platforms, there have been additional cuts to the CFTC's workforce and a wave of leadership departures under Trump's second term. Only one of five commissioner slots operating the agency is currently filled.

Still, other lawmakers calling for a stronger crack down on potential insider trading in prediction markets — particularly following suspicion around last week’s Maduro trade on Polymarket. On Friday, Democratic Rep. Ritchie Torres introduced a bill aimed at curbing government employees involvement in politically-related event contracts.

The bill has already gotten support from Kalshi CEO Tarek Mansour — who on LinkedIn maintained that insider trading has always been banned on his company's platform but that more needs to be done to crack down on unregulated prediction markets.

The Polymarket prediction market website is seen on a computer screen, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in New York. (AP Photo/Wyatte Grantham-Philips)

Polymarket prediction market website is displayed on a computer screen Friday, Jan. 9, 2026, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Wally Santana)

FILE - In this March 12, 2020, file photo, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro gives a press conference at the Miraflores presidential palace in Caracas, Venezuela. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix, File)