As Dr. Shane Wilson makes the rounds at the tiny, 25-bed hospital in rural northeastern Missouri, many of his movements are familiar in an age of coronavirus. Masks and gloves. Zippered plastic walls between hallways. Hand sanitizer as he enters and exits each room.

But one thing is starkly different. Born and raised in the town of just 1,800, Wilson knows most of his patients by their first names.

He visits a woman who used to be a gym teacher at his school, and later laughingly recalls a day she caught him smoking at school and made him and a friend pick up cigarette butts as punishment. Another man was in the middle of his soybean harvest when he fell ill and couldn’t finish.

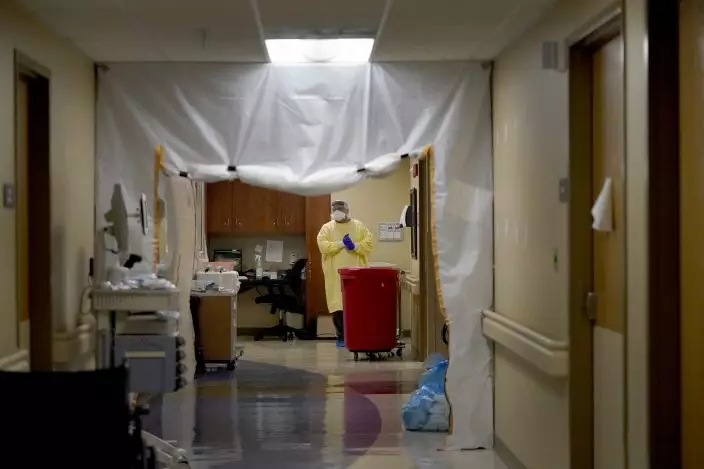

Dr. Shane Wilson stands inside a section of Scotland County Hospital set up to treat COVID-19 patients Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. As the coronavirus spreads in the rural northeast part of the state, doctors at the tiny hospital are already making difficult, often heartbreaking decisions about who they can take in and fear the situation is likely to get worse. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

In November, Wilson treated his own father, who along with his wife used to work at the same hospital. The 74-year-old elder Wilson recovered from the virus.

The coronavirus pandemic largely hit urban areas first, but the autumn surge is devastating rural America, too. The U.S. is now averaging more than 170,000 new cases each day, and it’s taking a toll from the biggest hospitals down to the little ones, like Scotland County Hospital.

The tragedy is smaller here, more intimate. Everyone knows everyone.

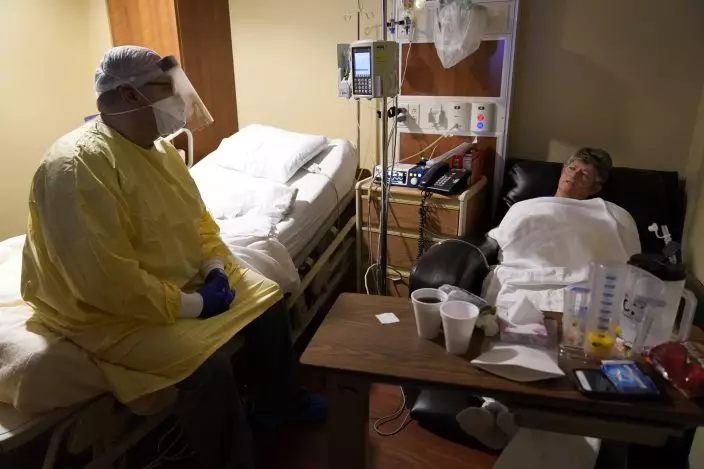

Dr. Shane Wilson, left, talks with COVID-19 patient Glen Cowell as the 68-year-old farmer rests in his bed inside Scotland County Hospital Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. Cowell started feeling sick around Nov. 11 before testing positive for coronavirus four days later. He gradually got worse and was eventually admitted to the hospital where cases are on the rise. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

Memphis, Missouri, population 1,800, is the biggest town for miles and miles amid the cornfields of the northeastern corner of Missouri. Agriculture accounts for most jobs in the region. The area is so remote that the nearest stoplight, McDonald’s and Wal-Mart are all an hour away, hospital public relations director Alisa Kigar said.

People come to the hospital from six surrounding counties, typically for treatment of things like farm and sports injuries, chest pains and the flu. Usually, there’s plenty of room.

Not now. The small hospital with roughly six doctors and 75 nurses among 142 full-time staff, is in crisis. The region is seeing a big increase in COVID-19 cases, and all available beds are usually taken.

Dr. Shane Wilson, right, touches the back of COVID-19 patient Glen Cowell while listening to Cowell's lungs through a stethoscope at Scotland County Hospital Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. Cowell didn't think much about the coronavirus until it knocked him to his knees a few weeks ago, eventually landing him in the only hospital for miles around in the remote northeastern part of Missouri. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

Scotland County Hospital’s doctors already are making difficult, often heartbreaking decisions about who they can take in. Wilson said some moderately ill people have been sent home with oxygen and told, “If things get worse, come back in, but we don’t have a place to put you and we don’t have a place to transfer you.”

Meanwhile, a staffing shortage is so severe that the hospital put out an appeal for anyone with health care experience, including retirees, to come to work. Several responded and are already on staff, including a woman working as a licensed practical nurse as she studies to become a registered nurse.

The hospital’s chief nursing officer, Elizabeth Guffey, said nurses are working up to 24 extra hours each week. Guffey sometimes sleeps in an office rather than go home between shifts.

Scotland County Hospital stands in the distance Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, nestled among homes in the small town of Memphis, Mo. The 25-bed facility, set up to serve patients from six surrounding counties for basic care in the rural northeast corner of the state, is starting to see a surge in COVID-19 cases. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

“We’re in a surge capacity almost 100% of the time,” Guffey said. “So it’s all hands on deck.”

It’s especially difficult to watch friends and relatives struggle through the illness while a large majority of the community still doesn’t take it seriously, she said.

“We spend our time indoors taking care of these very sick people, and then we go outdoors and hear people tell us the disease is a hoax or it doesn’t really exist,” Guffey said.

Registered nurse Brenna Smith administers a COVID-19 test to a drive-up patient outside Scotland County Hospital Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. Cases of coronavirus are on the rise in America stressing hospitals that serve rural areas like Scotland County. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

Glen Cowell wasn’t so sure about the virus until it knocked him to his knees.

At 68, Cowell still works his 500-acre farm near Memphis and is healthy enough that he takes no daily pills. He started feeling poorly around Nov. 11, tested positive four days later, then gradually got sicker. On Nov. 18, an ambulance took him to the emergency room. He was treated and went home.

“They only had one bed left and I didn’t feel I was sick enough to take somebody else’s bed,” Cowell said.

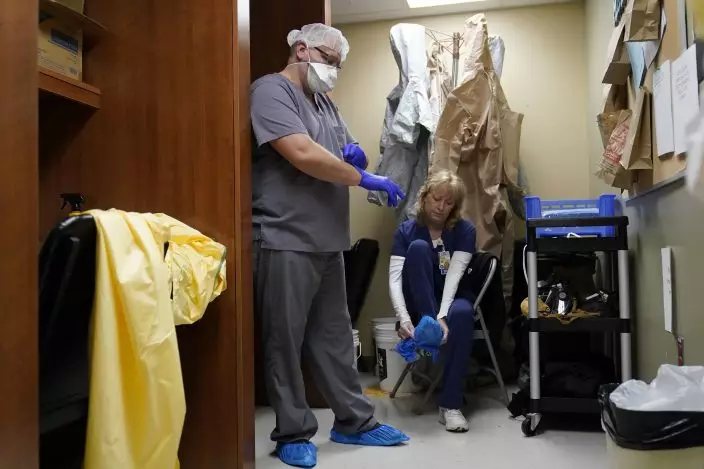

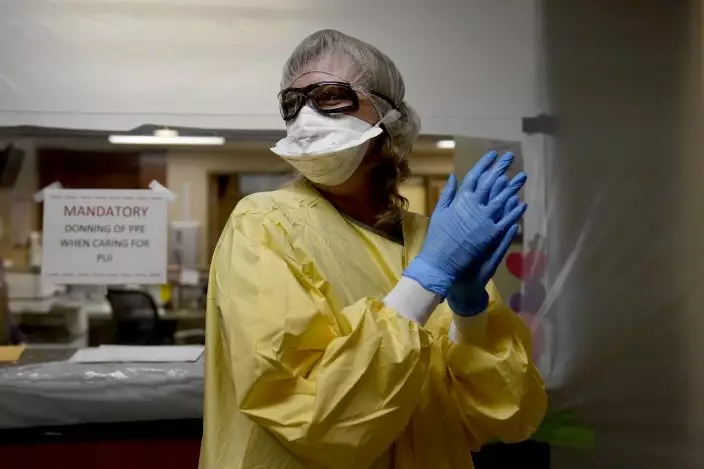

Dr. Shane Wilson, left, and registered nurse Shelly Girardin put on personal protective equipment before performing rounds in a portion of Scotland County Hospital set up to isolate and treat COVID-19 patients Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. The tiny hospital in rural northeast Missouri is seeing an alarming increase in coronavirus cases. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

But soon, breathing became difficult and nausea set in. Worst of all, his temperature spiked to 104 degrees. Another ambulance trip was followed by a lengthy hospital stay.

He’s not sure where he got the virus but admits he wasn’t overly cautious.

“I’m as independent as a hog on ice,” Cowell said. “I was pretty ambivalent about it. If Dollar General said I had to wear a mask, I wore a mask. If I walked across the street to Farm & Home, I didn’t wear a mask. I really wasn’t aware of the fact that it could get ahold of you and not let go.”

Registered nurse Shelly Girardin prepares to go on rounds after donning personal protective equipment inside an area of Scotland County Hospital sealed off with plastic to care for the influx of COVID-19 patients Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. The coronavirus pandemic is devastating rural hospitals, including the tiny 25-bed facility. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

Brock Slabach, senior vice president of the National Rural Health Association, based in suburban Kansas City, said it takes “space, staff and stuff” to run a rural hospital. “If you don’t have any one of those three, you’re really hamstrung,” he said, noting that many hospitals face shortages in all three areas.

Wilson spent hours on the phone one day, trying to find a larger hospital capable of providing the critical care that might save a man in his 50s who was critically ill with the virus.

By the time the University of Iowa Hospital agreed to take him, it was clear he couldn’t survive the 120-mile trip.

Emergency room nurse Linda Morgan sits at her desk inside Scotland County Hospital Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. As the coronavirus pandemic rages on in America, staff at the tiny hospital are dealing with the influx of COVID-19 patients and are being asked to work more and more hours as colleagues fall ill themselves. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

“I don’t know that getting him to Iowa City would have made a difference,” Wilson said. “Sometimes people are sick enough that they’re not going to survive, and that’s the reality of what we have to deal with. But it’s still pretty damn frustrating when you’re sitting here with your hands tied.”

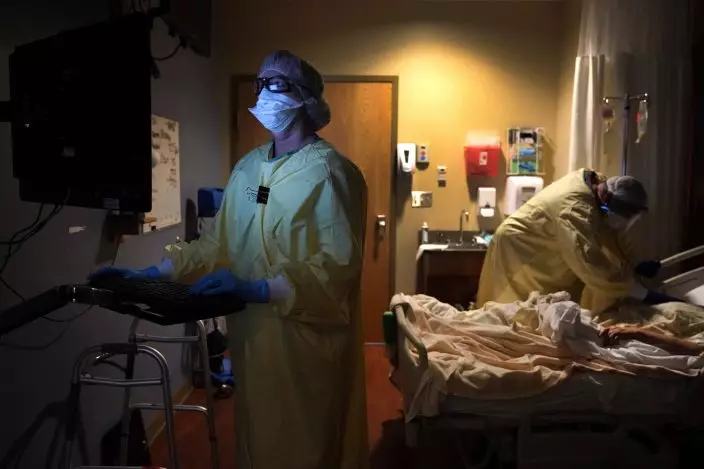

Registered nurse Shelly Girardin, left, is illuminated by the glow of a computer monitor as Dr. Shane Wilson examines COVID-19 patient Neva Azinger inside Scotland County Hospital on Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. The coronavirus pandemic largely hit urban areas first, but the autumn surge is now ravaging rural America, stressing the staffs of tiny hospitals like the one in Scotland County. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

Registered nurse Brenna Smith prepares a COVID-19 test for a drive-up patient at Scotland County Hospital Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. As new cases of coronavirus rise each day throughout the U.S, rural parts of America are being particularly hard hit. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

Dr. Shane Wilson, left, sits on a bed as he talks with COVID-19 patient JoBeth Harvey while performing rounds in a portion of Scotland County Hospital set up to isolate and treat COVID-19 cases on Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. Harvey used to be a gym teacher at Wilson's school and laughingly recalls a day she caught him smoking. She made him and a friend pick up cigarette butts as punishment. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

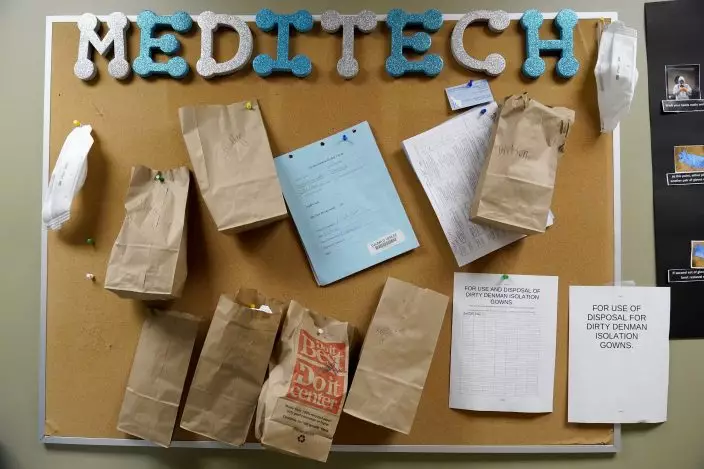

Paper bags containing N95 masks hang on a bulletin board waiting to be used again by staff inside a portion of Scotland County Hospital where COVID-19 patients have been isolated Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. The rural hospital is facing staffing shortages so severe that the hospital put out an appeal for anyone with health care experience, including retirees, to come to work. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

Marks are seen on the face of registered nurse Shelly Girardin as she removes a protective mask after performing rounds in a COVID-19 unit at Scotland County Hospital Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. The tiny hospital in rural northeast Missouri is seeing an alarming increase in coronavirus cases. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)

Housekeeping supervisor Ruth Addison decontaminates an examination room after a COVID-19 patient was treated inside at Scotland County Hospital Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020, in Memphis, Mo. (AP PhotoJeff Roberson)