His place in the history books about to be rewritten, President Donald Trump awaited his second impeachment -- something no other president has faced -- largely alone and silent.

For more than four years, Trump has dominated the national discourse like no one before him. That's just what made his position on the sidelines Wednesday, while his legacy was about to be permanently redefined, all the more stunning.

Trump would now stand with no equal, the only president to be charged twice with a high crime or misdemeanor, a new coda for a term defined by a deepening of the nation's divides, his failures during the worst pandemic in a century and his refusal to accept defeat at the ballot box.

President Donald Trump salutes as he steps off Air Force One upon arrival at Valley International Airport, Tuesday, Jan. 12, 2021, in Harlingen, Texas. (Miguel RobertsThe Brownsville Herald via AP)

Trump kept out of sight in a nearly empty White House as impeachment proceedings played out at the heavily fortified Capitol. There, the damage from last week’s riots provided a visible reminder of the insurrection that the president was accused of inciting.

Abandoned by some in his own party, Trump could do nothing but watch history unfold on television. The suspension of his Twitter account deprived Trump of his most potent means to keep Republicans in line, giving a sense that Trump had been defanged and, for the first time, his hold on his adopted party was in question.

With only a week left in Trump's term, there were no bellicose messages from the White House fighting impeachment and no organized legal response. Some congressional Republicans did defend the president during House debate in impeachment, their words carrying across the same space violated by rioters one week earlier during a siege of the citadel of democracy that left five dead.

President Donald Trump speaks with reporters as he walks to Air Force One upon departure, Tuesday, Jan. 12, 2021, at Andrews Air Force Base, Md. (AP PhotoAlex Brandon)

It was a marked change from Trump’s first impeachment. That December 2019 vote in the House, which made Trump only the third president ever impeached, played out along partisan lines. The charges then were that he had used the powers of the office to pressure Ukraine to investigate his political foe, now-President-elect Joe Biden.

At that time, the White House was criticized for failing to create the kind of robust “war room” that President Bill Clinton mobilized during his own impeachment fight. Nonetheless, Trump allies did mount their own pushback campaign. There were lawyers, White House messaging meetings, and a media blitz run by allies on conservative television, radio and websites.

Trump was acquitted in 2020 by the GOP-controlled Senate and his approval ratings were undamaged. But this time, as some members of his own party recoiled and accused him of committing impeachable offenses, Trump was isolated and quiet. A presidency centered on the bombastic declaration “I alone can fix it” seemed to be ending with a whimper.

The third-ranking Republican in the House, Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming, said there had “never been a greater betrayal” by a president. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., told colleagues in a letter that he had not decided how he would vote in an impeachment trial.

For the first time, Trump’s future seemed in doubt, and what was once unthinkable — that enough Republican senators would defy him and vote to remove him from office — seemed at least possible, if unlikely.

But there was no effort from the White House to line up votes in the president’s defense.

The team around Trump is hollowed out, with the White House counsel’s office not drawing up a legal defense plan and the legislative affairs team largely abandoned. Trump leaned on Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., to push Republican senators to oppose removal. Graham’s spokesman said the senator was making the calls of his own volition.

Trump and his allies believed that the president’s sturdy popularity with the lawmakers’ GOP constituents would deter them from voting against him.

The president was livid with perceived disloyalty from McConnell and Cheney and has been deeply frustrated that he could not hit back with his Twitter account, which has kept Republicans in line for years. Trump was expected to watch much of the day's proceedings on TV from the White House residence and his private dining area off the Oval Office.

His paramount concern, beyond his legacy, was what a second impeachment could do to his immediate political and financial future, according to four White House officials and Republicans close to the West Wing. They were not authorized to speak discuss private conversations and spoke on condition of anonymity.

The loss of his Twitter account and fundraising lists could complicate Trump's efforts to remain a GOP kingmaker and potentially run again in 2024. Moreover, Trump seethed at the blows being dealt to his business, including the withdrawal of a PGA tournament from one of his golf courses and the decision by New York City to cease dealings with his company.

A White House spokesman did not respond to questions about whether anyone in the building was trying to defend the president.

One campaign adviser, Jason Miller, was circulating a survey conducted by the president’s pollster earlier this week as he tried to make the case that voters would prefer the country skip impeachment and move on. Miller has argued Democrats’ efforts will serve to galvanize the Republican base behind Trump and end up harming Biden.

The only word from the president by midafternoon Wednesday was a two-sentence statement condemning violence. It was a message that was largely missing one week earlier, when rioters marching in Trump’s name descended on the Capitol to try to prevent Congress from certifying Biden's victory.

"In light of reports of more demonstrations, I urge that there must be NO violence, NO lawbreaking and NO vandalism of any kind,” Trump said in a statement released by the White House. “That is not what I stand for, and it is not what America stands for. I call on ALL Americans to help ease tensions and calm tempers.”

The reminders of the Capitol siege were everywhere as the House moved toward the impeachment roll call.

Some of the Capitol’s doors were broken and windows were shattered. A barricade had gone up around outside the building and there were new checkpoints. Hundreds of member of the National Guard patrolled the hallways, even sleeping on the marble floors of the same rotunda that once housed Abraham Lincoln’s casket.

And now the Capitol is the site of more history, adding to the chapter that features Clinton, impeached 21 years ago for lying under oath about sex with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, and Andrew Johnson, impeached 151 years ago for defying Congress on Reconstruction. Another entry is for Richard Nixon, who avoided impeachment by resigning during the Watergate investigation.

But Trump, the only one in line to be impeached twice, will once more be alone.

This story has been corrected to reflect that Trump was acquitted by the Senate in 2020, not 2019

WASHINGTON (AP) — For Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell and House Speaker Mike Johnson, the necessity of providing Ukraine with weapons and other aid as it fends off Russia's invasion is rooted in their earliest and most formative political memories.

McConnell, 82, tells the story of his father’s letters from Eastern Europe in 1945, at the end of World War II, when the foot soldier observed that the Russians were “going to be a big problem” before the communist takeover to come. Johnson, 30 years younger, came of age as the Cold War was ending.

As both men pushed their party this week to support a $95 billion aid package that sends support to Ukraine, as well as Israel, Taiwan and humanitarian missions, they labeled themselves “Reagan Republicans” an described the fight against Russian President Vladimir Putin in terms of U.S. strength and leadership. But the all-out effort to get the legislation through Congress left both of them grappling with an entirely new Republican Party shaped by former President Donald Trump.

While McConnell, R-Ky., and Johnson, R-La., took different approaches to handling Trump, the presumptive White House nominee in 2024, the struggle highlighted the fundamental battle within the GOP: Will conservatives continue their march toward Trump’s “America First” doctrine on foreign affairs or will they find the value in standing with America's allies? And is the GOP still the party of Ronald Reagan?

“I think we’re having an internal debate about that,” McConnell said in an interview with The Associated Press. “I’m a Reagan guy and I think today — at least on this episode — we turned the tables on the isolationists.”

Still, he acknowledged, “that doesn’t mean they’re going to go away forever.”

McConnell, in the twilight of his 18-year tenure as Republican leader, lauded a momentary victory Tuesday as a healthy showing of 31 Republicans voted for the foreign aid; that was nine more than had supported it in February. He said that was a trend in the right direction.

McConnell, who has been in the Senate since 1985, said passing the legislation was “one of the most important things I’ve ever dealt with where I had an impact."

But it wasn’t without cost.

He said last month he would step away from his job as leader next year after internal clashes over the money for Ukraine and the direction of the party.

For Johnson, just six months into his job as speaker, the political crosscurrents are even more difficult. He is clinging to his leadership post as right-wing Republicans threaten to oust him for putting the aid to Ukraine to a vote. While McConnell has embraced American leadership abroad his entire career, Johnson only recently gave complete support to the package.

Johnson has been careful not to portray passage as a triumph when a majority of his own House Republicans opposed the bill. He skipped a celebratory news conference afterward, describing it as “not a perfect piece of legislation” in brief remarks.

But he also borrowed terms popularized by Reagan, saying aggression from Russia, China and Iran “threatens the free world and it demands American leadership.”

“If we turn our backs right now, the consequences could be devastating,” he said.

Hard-line conservatives, including some who are threatening a snap vote on his leadership, are irate, saying the aid was vastly out of line with what Republican voters want. They condemned both Johnson and McConnell for supporting it.

“House Republican leadership sold out Americans and passed a bill that sends $95 billion to other countries,” said Republican Sen. Tommy Tuberville of Alabama, who opposed the bill. He said the legislation "undermines America's interests abroad and paves our nation's path to bankruptcy.”

Johnson has been lauded by much of Washington for doing what he called “the right thing" at a perilous moment for himself and the world.

“He is fundamentally an honorable person,” said Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., who brokered the negotiations and spent hours on the phone and in meetings with Johnson, McConnell and the White House.

Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, said Johnson and McConnell “both showed great resolve and backbone and true leadership at a time it was desperately needed.”

When McConnell began negotiations over President Joe Biden's initial aid request last year, he quickly set the terms for a deal. He and Schumer agreed to pair any aid for Ukraine with help for Israel, Schumer said, and McConnell demanded policy changes at the U.S. border with Mexico.

On McConnell's mind, he said, was that Trump was “unenthusiastic” about providing more aid to Kyiv. Yet McConnell, whose office displays a portrait of every Republican president since Reagan with the exception of Trump, had a virtually nonexistent relationship with the man he often refers to not by name, but simply as “the former president.”

Still, Trump would prove to hold powerful sway. When a deal on border security neared completion after months of work, Trump eviscerated the proposal as insufficient and a “gift” to Biden's reelection. Conservatives, including Johnson, rejected it out of hand.

With the border deal dead, McConnell pushed ahead with Schumer on the foreign aid, with the border policies stripped out, solidifying their unusual alliance. The Senate leaders met weekly throughout the negotiation.

“We disagreed on a whole lot, but we really stuck together,” Schumer said.

“We just persisted. We could not give up on this."

Meanwhile, a small group of GOP senators began working on an idea they thought could give Johnson some political wiggle room. Sens. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, Kevin Cramer of North Dakota and Markwayne Mullin of Oklahoma took an idea that Trump had raised — structuring the aid to Ukraine as a loan — and tried to make it reality.

Through a series of phone calls with Trump, several House members, as well as the speaker, they worked to structure roughly $9 billion in economic aid for Ukraine as forgivable loans — just as it was in the final package.

“Our approach this time was to make sure that the politics were set, meaning that President Trump is on board,” Mullin said.

The conversations culminated in Johnson making a quick jaunt to Florida, where he stood side by side with Trump at his Florida club just days before moving ahead with the Ukraine legislation in the House.

It was all enough, with Democratic help, to get the bill across the finish line. The legislation, which Biden signed into law on Wednesday, included some revisions from the Senate bill, including the loan structure and a provision to seize frozen Russian central bank assets to rebuild Ukraine. Nine GOP senators who had opposed the first version of the bill swung to “yes” largely because of the changes Johnson had made.

The result was a strong showing for the foreign aid in the Senate, even though the decision could prove costly for Johnson.

What comes next on Ukraine is anyone's guess.

While the $61 billion for Ukraine in the package is expected to help the country withstand Moscow's offensive this year, more assistance will surely be needed. Republicans, exhausted after a grueling fight, largely shrugged off questions about the future.

“This one wasn’t easy,” Mullin said.

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

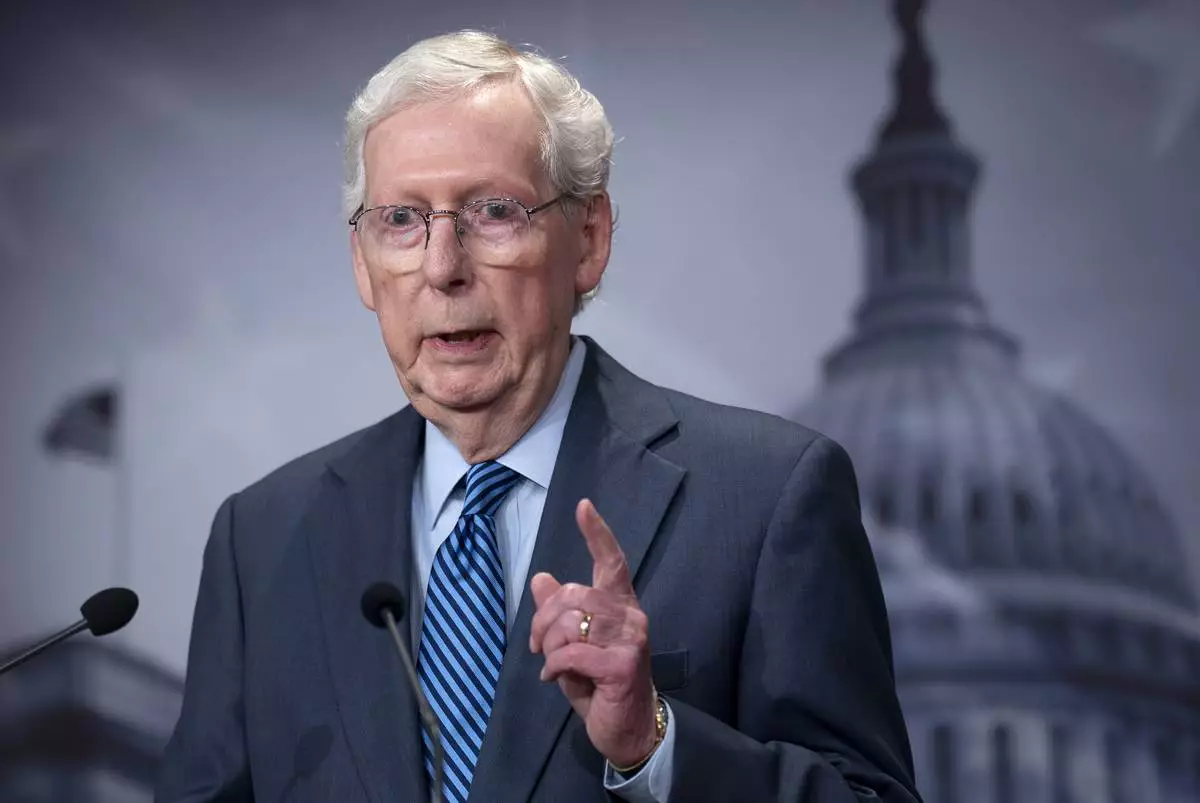

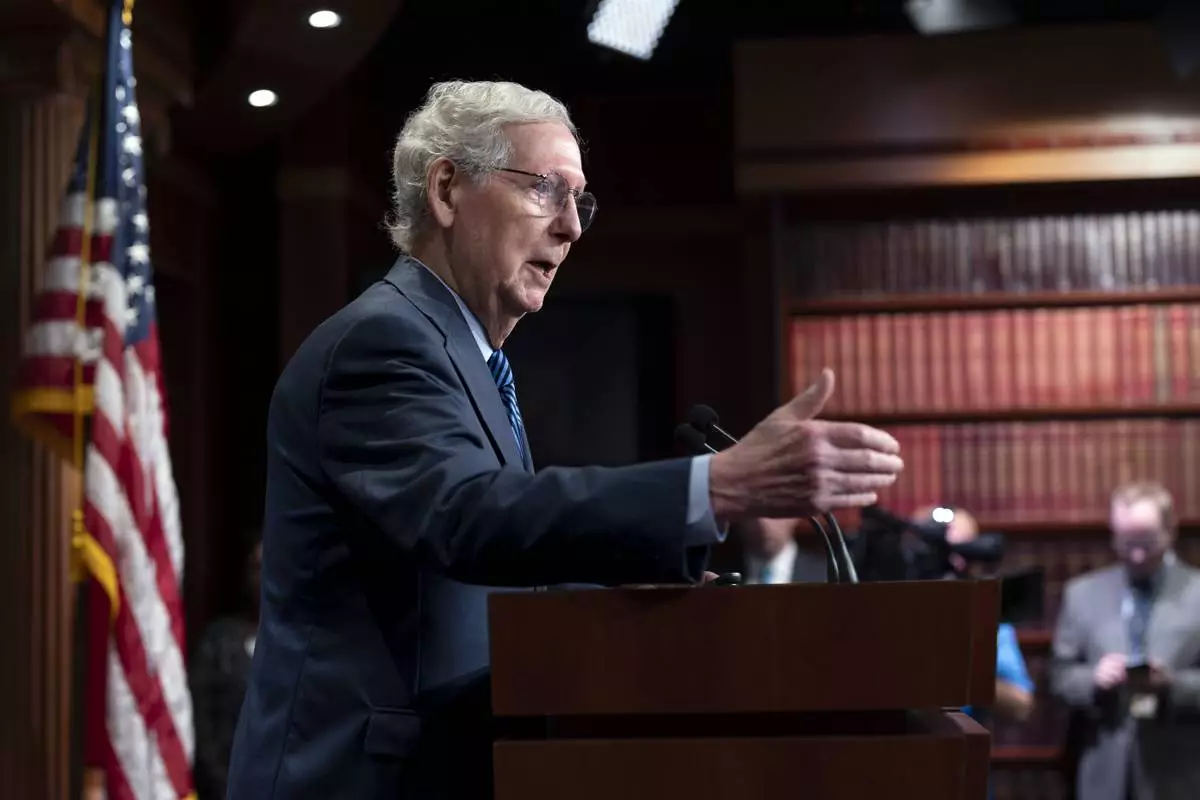

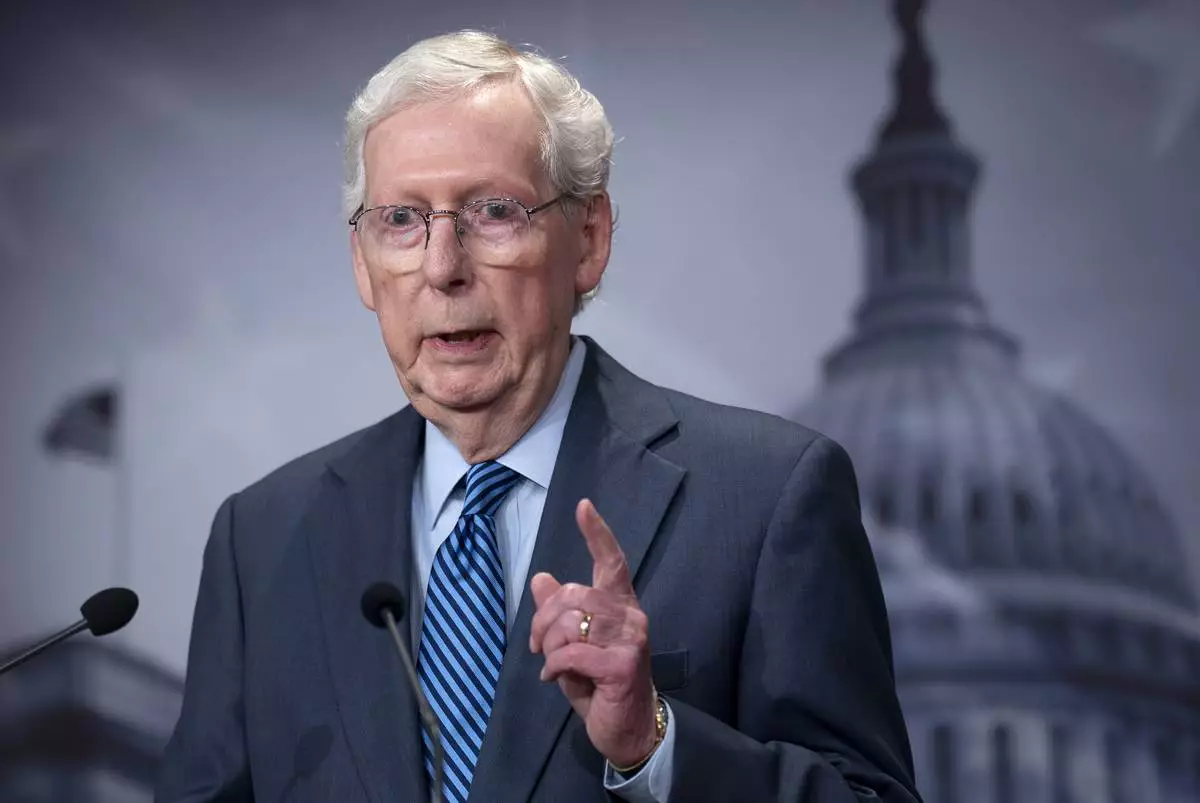

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., praises support for Ukraine as the Senate is on track to pass $95 billion in war aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., praises support for Ukraine as the Senate is on track to pass $95 billion in war aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to reporters just after the House voted to approve $95 billion in foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and other U.S. allies, at the Capitol in Washington, Saturday, April 20, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., walks to the chamber as the Senate prepares to advance the $95 billion aid package for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan passed by the House, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)