The Biden administration said Thursday it was delaying a rule finalized in former President Donald Trump's last days in office that would have drastically weakened the government's power to enforce a century-old law protecting most wild birds.

U.S. wildlife officials have said the rule could mean more birds die, including those that land in oil pits or collide with power lines or other structures. But under Trump, the Interior Department sided with industry groups that had long sought to end criminal prosecutions of accidental but preventable bird deaths.

While the new rule had been set to go into effect on Feb. 8, The Associated Press obtained details of the delay ahead of an expected announcement Thursday. Interior Department officials said they were putting off the rule at Biden's direction and will open the issue to a 30-day public comment period.

FILE - In this March 29, 2020, file photo, a bird flies among wind turbines near King City, Mo. The Trump administration is moving to scale back criminal enforcement of a century-old law protecting most American wild bird species. The former director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told AP billions of birds could die if the government doesn't hold companies liable for accidental bird deaths. (AP PhotoCharlie Riedel, File)

“The Migratory Bird Treaty Act is a bedrock environmental law critical to protecting migratory birds and restoring declining bird populations," Interior spokeswoman Melissa Schwartz said. “The Trump administration sought to overturn decades of bipartisan and international precedent in order to protect corporate polluters.”

A federal judge in August had blocked the Trump administration's prior attempt to change how the Migratory Bird Treaty Act was enforced. The Trump administration remained adamant that the law had been wielded inappropriately for decades to penalize companies and other entities that kill birds accidentally.

The highest-profile enforcement case bought under the law resulted in a $100 million settlement by energy company BP after the 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil spill killed about 100,000 birds.

FILE - In this Jan. 10, 2009, file photo, a flock of geese fly past a smokestack at a coal power plant near Emmitt, Kan. The Trump administration is moving to scale back criminal enforcement of a century-old law protecting most American wild bird species. The former director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told AP billions of birds could die if the government doesn't hold companies liable for accidental bird deaths. (AP PhotoCharlie Riedel, File)

More than 1,000 species are covered under the migratory bird law, and the move to lessen enforcement standards drew a sharp backlash from organizations that advocate on behalf of an estimated 46 million U.S. birdwatchers. It came at a time when species across North America already were in steep decline.

A Trump administration analysis of the rule change did not put a number on how many more birds could die. But it said some vulnerable species could decline to the point that they would require protection under the Endangered Species Act.

Former federal officials and scientists had said billions more birds could have died in coming decades under Trump's new rule.

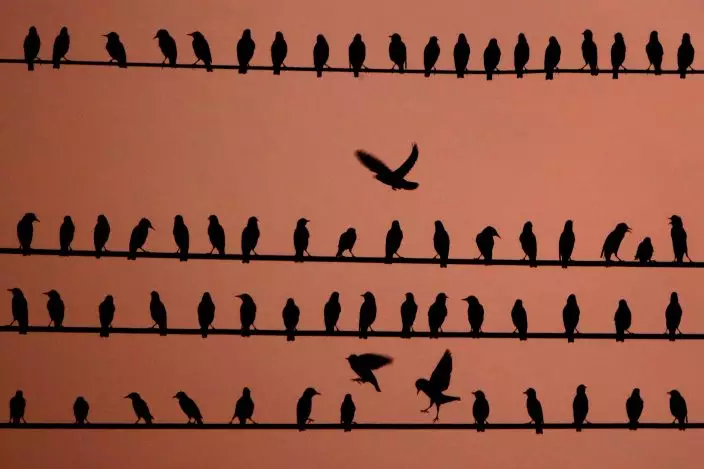

FILE- In this Sept. 24, 2017, file photo, birds vie for position on power lines at dusk in Kansas City, Kan. The Trump administration is moving to scale back criminal enforcement of a century-old law protecting most American wild bird species. The former director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told AP billions of birds could die if the government doesn't hold companies liable for accidental bird deaths. (AP PhotoCharlie Riedel, File)

Industry sources and other human activities — from oil pits and wind turbines, to vehicle strikes and glass building collisions — now kill an estimated 460 million to 1.4 billion birds annually, out of an overall 7.2 billion birds in North America, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and recent studies.

Researchers say cats are the biggest single source of deaths, killing more than 2 billion birds a year.

Many companies have sought to reduce bird deaths in recent decades by working with wildlife officials, but the incentive to participate drops without the threat of criminal liability.

FILE - In this Oct. 5, 2015, file photo, Dan Ashe, then-director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, talks following an animal release at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in Commerce City, Colo. Former U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Ashe told The Associated Press that the Migratory Bird Treaty Act's threat of prosecution served as "a brake on industry" that had saved probably billions of birds. (AP PhotoDavid Zalubowski, File)

The 1918 migratory bird law became after many U.S. bird populations had been decimated by hunting and poaching — much of it for feathers for women’s hats.

Follow Matthew Brown on Twitter: @matthewbrownap