Hardship felt during the COVID-19 pandemic has spurred European Union leaders to add muscle to the bloc's safeguards for its 450 million citizens in welfare, jobs and gender equality.

But not everybody’s impressed by their good intentions, which are non-binding for the bloc's 27 governments.

EU leaders held a summit in Porto, Portugal on Friday to discuss how they can ensure “equal opportunities for all and that no one is left behind.”

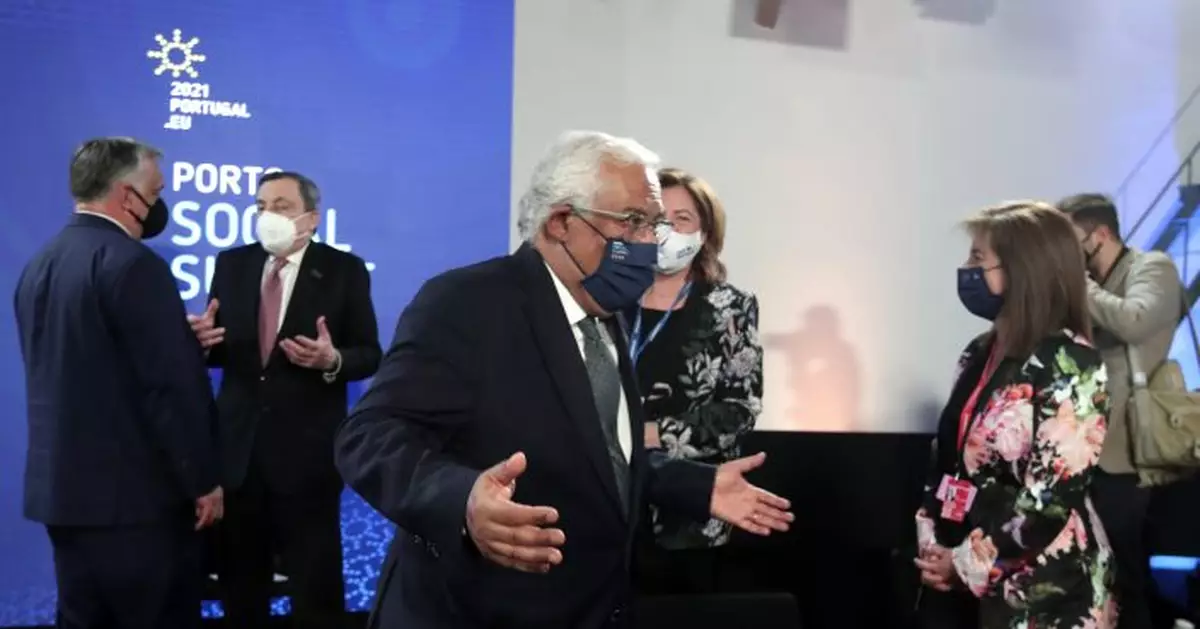

Portugal's Prime Minister Antonio Costa, right, speaks with Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban, left, and Italy's Prime Minister Mario Draghi, center, during the opening ceremony of an EU summit at the Alfandega do Porto Congress Center in Porto, Portugal, Friday, May 7, 2021. European Union leaders are meeting for a summit in Portugal on Friday, sending a signal they see the threat from COVID-19 on their continent as waning amid a quickening vaccine rollout. Their talks hope to repair some of the damage the coronavirus has caused in the bloc, in such areas as welfare and employment. (AP PhotoLuis Vieira, Pool)

The plans and promises contained in a summit draft declaration on social rights, obtained by The Associated Press, are ambitious.

“As Europe gradually recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, the priority will be to move from protecting to creating jobs and to improve job quality,” the declaration states.

The leaders say they are “committed to reducing inequalities, defending fair wages, fighting social exclusion and tackling poverty.”

They also vow to “step up efforts to fight discrimination and work actively to close gender gaps in employment, pay and pensions.”

However, the U.N. special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Olivier De Schutter, was critical of the plan, saying in a statement it is “insufficiently ambitious.”

That’s because countries which miss targets in the plan suffer no consequences. Also, there is no mechanism for Europeans to hold their governments accountable if they don’t abide by the program.

Already, 11 EU countries last week reminded European authorities that social policy is set by sovereign national governments, not Brussels — suggesting they don't feel obliged to comply with the program.

The European Trade Union Confederation, which represents 45 million members in 38 European countries, rebuked the 27 EU leaders, too.

Its general secretary, Luca Visentini, said that “less talk and more action (is) needed” from governments.

“We have to be very clear that legislation and money are the only things that can really make a difference. All the rest is blah blah,” Visentini said in a statement.